Ivan Tykhyi/Getty

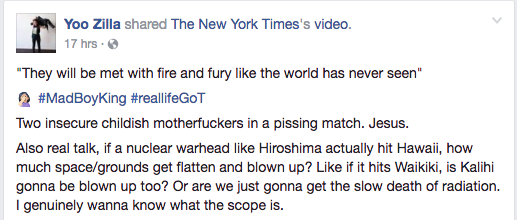

Yesterday Trump dropped a barrage of F-words, no doubt to match the colorful language emanating from Pyongyang, stating North Korea will "face fire and fury like the world has never seen." According to a recent poll, two-thirds of Americans now view North Korea as a "very serious threat." In Hawaii, however—one of several likely targets within range of a North Korean ICBM—it's probably closer to 100 percent. Whatever Trump (and John Kelly) get up to, it's the lives of Hawaiian, Guamanian, Korean, and Japanese residents he is risking with his threatening alliteration.All of this has set Hawaiian social media ablaze with posts—for instance, an apt question on Facebook from Yoo Zilla: "If it hits Waikiki, is Kalihi gonna be blown up too? Or are we just gonna get the slow death of radiation." Hawaii recently revamped its nuclear contingency plan, and CNN recently documented the process of how the Department of Defense would go about sounding the alarms after detecting an ICBM. It has Hawaiian citizens not just pondering but actually picturing and planning where to hide during the 15-minute warning they would receive before nuclear fallout. It's scary.Moreover, it has Hawaii doctors like me reviewing contingency plans for the would-be massive influx of wounded and injured people if an ICBM was to strike. In Hiroshima and Nagasaki, nearly 200,000 people died acutely after Fat boy and Little Man were dropped; both were much less powerful bombs than what we have available today. Untold more suffered and died from the deleterious effects of radiation poisoning.Getting blown up is fairly self explanatory, but the sometimes quick, sometimes slow death of radiation poisoning all depends on the dose of radiation received. It is a complex formula, but the most important factors are: proximity to the bomb epicenter, whether you are inside a solid structure or exposed without cover outside, the type of bomb North Korea would use, and prevailing winds. It's difficult to estimate what size and type of bomb North Korea currently has in its arsenal, but most sources estimate its latest test in 2013 at 10 kilotons. (If you're ever bored or looking to be terrified, you can visualize the destruction and fallout in your home town by past nuclear detonations with this doomsday online simulator.)The radiation spit from a nuclear bomb spans the entire magnetic spectrum and comes in two categories: non-ionizing and ionizing. Non-ionizing radiation, such as radio and microwaves are lower energy, but can cause thermal burns. The more potent ionizing radiation such as alpha and beta particles, positrons, neutrons, and especially X-rays and gamma rays can cause DNA errors, cell death, and lead to the deadly acute radiation syndrome.Alpha particles—which consist of two protons and two neutrons—are large enough to be blocked by a single piece of paper or the outer layers of your skin. The latter consists mainly of dead skin cells, so unless the radiation material is ingested, alpha particles pose little comparable risk to other forms of radiation.Beta particles are a single electron, and a positron is a positively charged electron. Their smaller size allows them to penetrate exposed skin more easily, but they don't penetrate clothes. Beta particles can cause serious burns that—unlike traditional heat burns—evolve and worsen over the course of several weeks due to dose-dependent rates of DNA destruction and cell death. They're treated using traditional methods such as dressings, removing dead tissue, and skin grafting, if warranted.Neutrons and gamma/x-rays sit at the top of the energy spectrum, high enough to require concrete or lead shielding, without which they're impossible to avoid. They will cause whole body irradiation and penetrate centimeters into human tissue. High doses of these pose the greatest risk for acute radiation poisoning and death.The dose of radiation can be measured, and the traditional unit of measuring is called the gray (Gy). To put a dose of 1 gray in perspective, the background radiation we are all exposed to when living on earth for one year is 0.0062 Gy. A Chest X-Ray is 0.00001 Gy, a CT Scan of the abdomen 0.01 Gy. During nuclear fallout, doses reach anywhere from 2 Gy to more than 30 Gy. That's the equivalent of 3 million chest x-rays.The burns caused by radiation are worse depending on how much you've been exposed to (a result of the type of bomb used and how far and how protected from the blast you are), and evolve over weeks. A localized blast of 15 to 20 Gy of all the particles and rays described above to an exposed arm or leg (which is less likely to happen in a nuclear blast unless only part of a body is in the open) will cause an initial week of transient redness, sensitivity, and itching. The second week will reveal persistent redness and hair loss, followed by by a third week of swelling and pain. By the fourth week, the wound will ulcer, and skin sloughing will occur. If the localized dose is more than 50 Gy, the area will behave more like a traditional heat burn, and will cause immediate pain and blistering.Acute radiation syndrome occurs when whole-body gamma radiation reaches 2 Gy. It can be divided into four phases: prodrome, latent phase, illness phase, and recovery. The length of these phases—and if recovery will even be achieved—are again dependent on how much radiation you've been exposed to. The commonly accepted dose of whole-body gamma radiation to cause death in 50 percent of the population, termed LD50 , is about 3.5 Gy.Much like in chemotherapy, the first cells to be affected are the rapidly dividing cells of the intestines and bone marrow.The prodromal phase is miserable and akin to the flu, causing vomiting, lack of appetite, diarrhea, fever, sweating, muscle aches, and fatigue. This is followed by the latent—or symptom- free—period, which can be as long as one to three weeks if the dose was less than 4 Gy, or just a few hours if it's greater than 15 Gy.During the illness phase, acute radiation syndrome will affect the bone marrow and destroy white blood cells, hampering immunity, and lead to infections. The bone marrow will stop making clot-forming platelet cells, predisposing people to spontaneous hemorrhages. The intestinal lining sloughs away, causing severe nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and pain, leading to massive fluid and electrolyte losses, and even translocation of gut bacteria into the bloodstream.If whole-body radiation is greater than 20 to 30 Gy, immediate low blood pressure, vomiting, and explosive bloody diarrhea occur. That's followed within hours by seizures, disorientation, and tremors. Death usually occurs within 72 hours.Some of the deleterious effects of acute radiation syndrome can be mitigated by emergency care—replacing blood products, giving antibiotics, using breathing machines, and dialysis. But when hospitals are inundated with patients, as would be the case with a nuclear explosion, resources would be quickly outpaced by demand. It's not a future anybody can stomach, and it makes President Trump's barrage of F-words feel that much more careless.

Darragh O'Carroll, MD, is an emergency physician in Hawaii.

Read This Next: How to Survive the First Hour of a Nuclear Attack

Hawaii recently revamped its nuclear contingency plan, and CNN recently documented the process of how the Department of Defense would go about sounding the alarms after detecting an ICBM. It has Hawaiian citizens not just pondering but actually picturing and planning where to hide during the 15-minute warning they would receive before nuclear fallout. It's scary.Moreover, it has Hawaii doctors like me reviewing contingency plans for the would-be massive influx of wounded and injured people if an ICBM was to strike. In Hiroshima and Nagasaki, nearly 200,000 people died acutely after Fat boy and Little Man were dropped; both were much less powerful bombs than what we have available today. Untold more suffered and died from the deleterious effects of radiation poisoning.Getting blown up is fairly self explanatory, but the sometimes quick, sometimes slow death of radiation poisoning all depends on the dose of radiation received. It is a complex formula, but the most important factors are: proximity to the bomb epicenter, whether you are inside a solid structure or exposed without cover outside, the type of bomb North Korea would use, and prevailing winds. It's difficult to estimate what size and type of bomb North Korea currently has in its arsenal, but most sources estimate its latest test in 2013 at 10 kilotons. (If you're ever bored or looking to be terrified, you can visualize the destruction and fallout in your home town by past nuclear detonations with this doomsday online simulator.)The radiation spit from a nuclear bomb spans the entire magnetic spectrum and comes in two categories: non-ionizing and ionizing. Non-ionizing radiation, such as radio and microwaves are lower energy, but can cause thermal burns. The more potent ionizing radiation such as alpha and beta particles, positrons, neutrons, and especially X-rays and gamma rays can cause DNA errors, cell death, and lead to the deadly acute radiation syndrome.Alpha particles—which consist of two protons and two neutrons—are large enough to be blocked by a single piece of paper or the outer layers of your skin. The latter consists mainly of dead skin cells, so unless the radiation material is ingested, alpha particles pose little comparable risk to other forms of radiation.Beta particles are a single electron, and a positron is a positively charged electron. Their smaller size allows them to penetrate exposed skin more easily, but they don't penetrate clothes. Beta particles can cause serious burns that—unlike traditional heat burns—evolve and worsen over the course of several weeks due to dose-dependent rates of DNA destruction and cell death. They're treated using traditional methods such as dressings, removing dead tissue, and skin grafting, if warranted.Neutrons and gamma/x-rays sit at the top of the energy spectrum, high enough to require concrete or lead shielding, without which they're impossible to avoid. They will cause whole body irradiation and penetrate centimeters into human tissue. High doses of these pose the greatest risk for acute radiation poisoning and death.The dose of radiation can be measured, and the traditional unit of measuring is called the gray (Gy). To put a dose of 1 gray in perspective, the background radiation we are all exposed to when living on earth for one year is 0.0062 Gy. A Chest X-Ray is 0.00001 Gy, a CT Scan of the abdomen 0.01 Gy. During nuclear fallout, doses reach anywhere from 2 Gy to more than 30 Gy. That's the equivalent of 3 million chest x-rays.The burns caused by radiation are worse depending on how much you've been exposed to (a result of the type of bomb used and how far and how protected from the blast you are), and evolve over weeks. A localized blast of 15 to 20 Gy of all the particles and rays described above to an exposed arm or leg (which is less likely to happen in a nuclear blast unless only part of a body is in the open) will cause an initial week of transient redness, sensitivity, and itching. The second week will reveal persistent redness and hair loss, followed by by a third week of swelling and pain. By the fourth week, the wound will ulcer, and skin sloughing will occur. If the localized dose is more than 50 Gy, the area will behave more like a traditional heat burn, and will cause immediate pain and blistering.Acute radiation syndrome occurs when whole-body gamma radiation reaches 2 Gy. It can be divided into four phases: prodrome, latent phase, illness phase, and recovery. The length of these phases—and if recovery will even be achieved—are again dependent on how much radiation you've been exposed to. The commonly accepted dose of whole-body gamma radiation to cause death in 50 percent of the population, termed LD50 , is about 3.5 Gy.Much like in chemotherapy, the first cells to be affected are the rapidly dividing cells of the intestines and bone marrow.The prodromal phase is miserable and akin to the flu, causing vomiting, lack of appetite, diarrhea, fever, sweating, muscle aches, and fatigue. This is followed by the latent—or symptom- free—period, which can be as long as one to three weeks if the dose was less than 4 Gy, or just a few hours if it's greater than 15 Gy.During the illness phase, acute radiation syndrome will affect the bone marrow and destroy white blood cells, hampering immunity, and lead to infections. The bone marrow will stop making clot-forming platelet cells, predisposing people to spontaneous hemorrhages. The intestinal lining sloughs away, causing severe nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and pain, leading to massive fluid and electrolyte losses, and even translocation of gut bacteria into the bloodstream.If whole-body radiation is greater than 20 to 30 Gy, immediate low blood pressure, vomiting, and explosive bloody diarrhea occur. That's followed within hours by seizures, disorientation, and tremors. Death usually occurs within 72 hours.Some of the deleterious effects of acute radiation syndrome can be mitigated by emergency care—replacing blood products, giving antibiotics, using breathing machines, and dialysis. But when hospitals are inundated with patients, as would be the case with a nuclear explosion, resources would be quickly outpaced by demand. It's not a future anybody can stomach, and it makes President Trump's barrage of F-words feel that much more careless.

Darragh O'Carroll, MD, is an emergency physician in Hawaii.

Read This Next: How to Survive the First Hour of a Nuclear Attack

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement