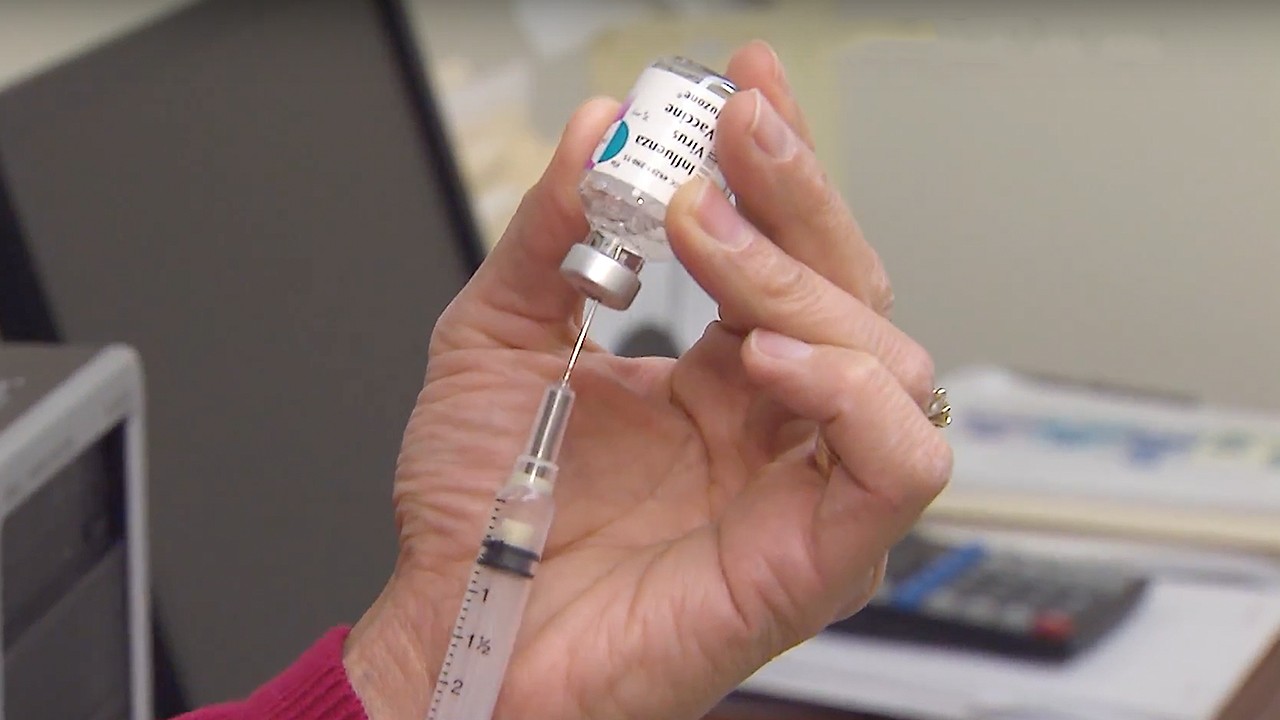

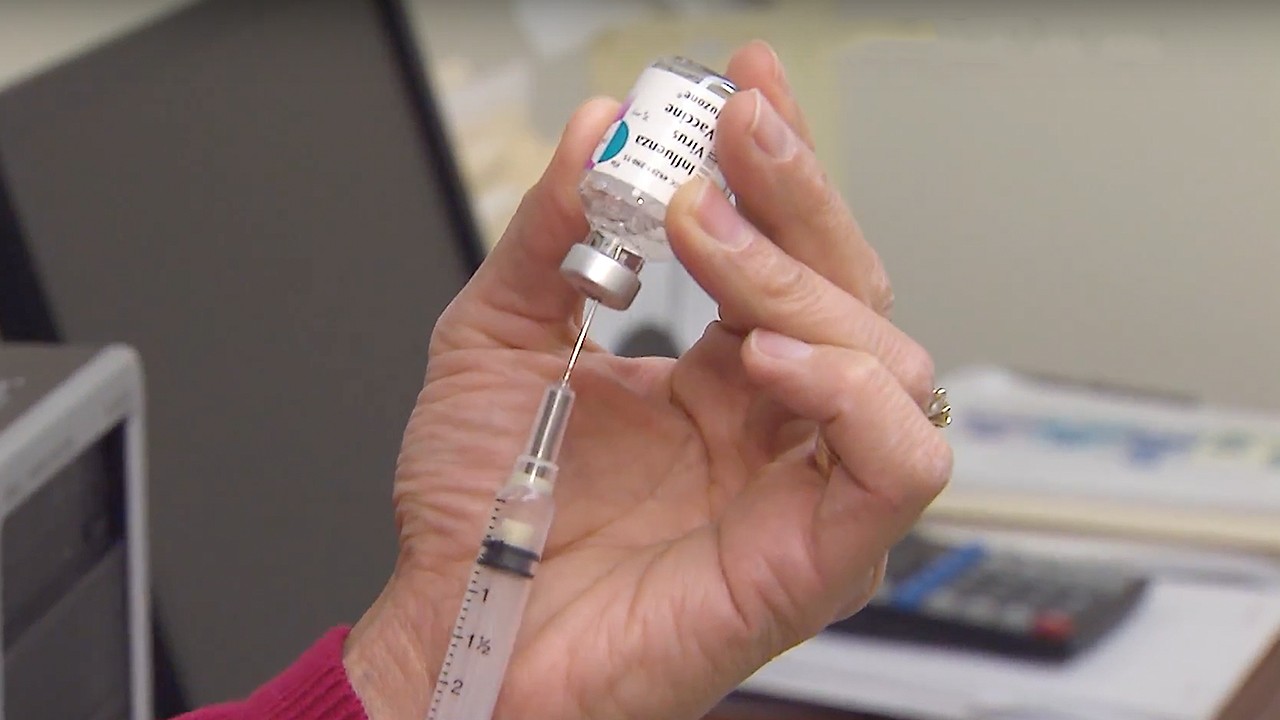

Stock photos via Getty

Sarah has become an expert at talking hospitals into giving her lower prices. The 30-something suffers from an autoimmune disease and also has BRCA, the so-called breast cancer gene, so she’s spent a fair amount of time in doctors’ offices, hospitals, and imaging facilities. She estimates she’s spent an almost equal amount of time on the phone with providers’ billing departments and with her health insurance company, fighting or negotiating the cost of her care.“I was always one to fight bills,” she told me. “My mom taught me that. She was a union leader and liked bargains.” Sarah, who requested I not use her full name to protect her privacy, has employer insurance through her ex-husband. They split two years ago, but have remained legally married so that she can have insurance. She’s not sure how much longer that will last. But even with insurance, she’s become an expert at negotiating prices for services and getting her bills reduced whenever she senses an error or overcharge. Which happens a lot.“I had a mammogram at a hospital and I got a bill for it. Those are supposed to be free. They were charging me hundreds of dollars,” she said. When she called, the hospital’s billing department told her that the charge was because she had BRCA. “They were trying to tell me my mammogram cost more because I had a grandmother who had cancer. I sent a letter to every email that I could find in the hospital.” It took her six months, but eventually she got the charge removed.Her strategy: persistence, and, in some cases simply saying she’s not able to pay the bill. She always records the conversations and sometimes threatens that she has an attorney (even though she can’t afford one). “It’s like a part-time job pursuing it,” she said.It doesn’t always work, but for her, it’s worth the effort. Over the years, she’s avoided paying nearly $5,000 worth of bills. And though arguing with billing departments is unpleasant and time-consuming, it’s become a necessity for many people. According to Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), a nonprofit that analyzes healthcare issues, 81 percent of people with employer insurance have a deductible that must be paid by the patient before the insurer starts paying for most sorts of care. If you buy insurance through the Affordable Care Act marketplace, you’re dealing with rising premiums and out-of-pocket maximums. And the Trump administration has made choices that make things worse: In October, it announced a plan to end subsidies to insurers designed to reduce costs for low-income Americans, and many insurers increased premiums as a result.“Consumers are very much at the mercy of the system,” said Karen Pollitz, a senior fellow at KFF. “Prices are pretty irrational in the US and they’re all over the map. We’re the only place where there are 1,000 difference prices for a chest X-ray (and) it doesn’t seem to bear relationship to cost, it’s just a random array of prices.”

There are resources for consumers trying to grapple with this opaque and often nonsensical system. The website Healthcare Bluebook allows patients to search a database to find the “fair price” for procedures. The fair price is based on data the company studies and represents an amount that many providers accept from an insurance company for a service in a given area. For example, in Cleveland, the fair price for a dental cleaning is $75, according to the site.“Healthcare is this insane transaction where you have no choice but to consume the good, you’re forbidden from knowing the price before you consume the good, and you’re legally required to pay whatever bill they send you after the fact,” said Bill Kampine, co-founder of Healthcare Bluebook. “None of us would enter into any transaction under those terms—buying a cell phone or tires or anything. But for some odd reason, we do it in healthcare.”Healthcare Bluebook often lists providers who offer discounts if patients pay cash up front. Many doctors and hospitals offer cash discounts for uninsured patients, but more and more insured patients are taking advantage of those discounts as well, circumventing insurance all together.“That has to do with more and more people having high deductibles,” Kampine told me. “Years ago, everybody paid their $25 (co-pay), the bill was sent to the insurance company, and the insurance company paid the balance. Now, a huge proportion of those patients all have to pay the first $3,000. They (providers) send out the bills, and no one’s got $3,000 in their bank account, they’re on the hook for it.”But even the cash discounts, say many experts, are arbitrary.“It’s a bit like Macy’s saying, ‘This $500 dress is on sale for $75,’ and you feel like it’s such a great bargain, you take it. But it was never $500, right? That’s a made-up number,” said Pollitz.To take one example, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles offers cash discounts to in-network insured patients for a handful of procedures, including 3D mammography and the Automated Breast Ultrasound Screening (ABUS). The ABUS is a supplement to mammograms for women with dense breasts. (Around 40 to 50 percent of women over 40 have dense breasts, which make mammograms more difficult to read.) If a patient pays $395 upfront, the hospital won’t submit a claim to an insurer. For the patient, it feels like a deal—the billed price is over $2,000. Even though the hospital has a participating agreement with the insurance companies, they’re still allowed to offer side deals on certain procedures.Cedars-Sinai would not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story, but when I called their imaging department saying I was a patient, they confirmed they offered this all the time. When I called my insurance company, they told me the procedure was not covered until a patient met her deductible. The representative I spoke to was familiar with hospitals offering these cash deals, and said that hospitals were allowed to do that even if patients had insurance.After several phone calls to my provider and the insurance company, I learned that because my doctor and I had a conversation about particular health concerns during the visit, the nature of the appointment changed. “Your vitamin D numbers were low,” the supervisor from the provider’s billing department told me on the phone. (I didn’t understand why someone in the billing department knew everything I discussed with my personal physician and how that wasn’t a violation of HIPAA law, which protects privacy of medical information. “It just wasn’t,” the supervisor told me.)The insurance company confirmed that my visit did not qualify as preventive, and then outlined the very specific parameters for preventive care. If, during a yearly physical, one utters the sentence, “I had a headache,” for example, the visit instantly goes from costing nothing to costing the price of an office visit co-pay.Sarah sometimes wonders why she has insurance in the first place. She has an upcoming breast-related surgery, and she cut a cash deal with an out-of-network hospital, based on her financial need, that will be less expensive—and with no surprise costs—than if she had done it in network.“The funny thing is, there’s this charade of all these rules and the rules are designed against us,” Sarah said. “But then, one doctor here is willing to bend them, another doctor isn’t. So why are there rules?”Of course, insurance can be vital in cases when the unpredictable strikes: Years ago, Kampine had a “potentially catastrophic diagnosis and those bills alone were in excess of $100,000. Absent insurance, that would have bankrupted me,” he said.“It’s completely confounding for consumers,” said Pollitz. “In particular when consumers are sick—then we call them ‘patients.’ It’s not a good time to start doing research, polishing up your economic negotiating skills, and reading the federal register. You’re sick, you’re scared, there’s a lump. You need to get it checked out. You are not an economic actor at that point. You are a sick person.”Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.Cole Kazdin is a writer living in Los Angeles.

Advertisement

Advertisement

There are resources for consumers trying to grapple with this opaque and often nonsensical system. The website Healthcare Bluebook allows patients to search a database to find the “fair price” for procedures. The fair price is based on data the company studies and represents an amount that many providers accept from an insurance company for a service in a given area. For example, in Cleveland, the fair price for a dental cleaning is $75, according to the site.“Healthcare is this insane transaction where you have no choice but to consume the good, you’re forbidden from knowing the price before you consume the good, and you’re legally required to pay whatever bill they send you after the fact,” said Bill Kampine, co-founder of Healthcare Bluebook. “None of us would enter into any transaction under those terms—buying a cell phone or tires or anything. But for some odd reason, we do it in healthcare.”Healthcare Bluebook often lists providers who offer discounts if patients pay cash up front. Many doctors and hospitals offer cash discounts for uninsured patients, but more and more insured patients are taking advantage of those discounts as well, circumventing insurance all together.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Kampine is a big proponent of comparison shopping when it’s possible. In the case of labs and imaging, he suggests calling independent facilities, seeing if they take your insurance, and getting a price quote. It might be lower than the place your doctor is referring you to, and still in network. If a person doesn’t have insurance, they can call providers and ask the cash price they offer to uninsured patients.I pick up the phone any time a bill looks suspect. I was once charged hundreds of dollars for a consult with a specialist that should have been a $55 copay. After several phone calls, I finally learned that the provider charged me for an outpatient hospital visit instead of a regular appointment because I had visited the doctor in a particular building. I explained this to about ten different people and finally reached a supervisor with the insurance company who eventually conceded, “OK, just this once,” and changed the charge back to an office visit.I’ve lost many of these battles as well. Last year, I was charged a $35 copay for my yearly physical, which is, legally, supposed to be free. (All marketplace plans like mine must cover certain services, like preventive care visits and, for women over 40, yearly mammograms, without charging a co-payment or co-insurance, even if a person hasn’t reached their deductible.)I was once charged hundreds of dollars for a consult with a specialist that should have been a $55 copay.

Advertisement