It is painful to come from a country that no one recognises as legitimate.

I have swum in the sea in northern Cyprus, and knocked on its watermelons, and thrown water-bombs into its dust, and slept on its flat roofs under a sky dense with stars. I have shelled black-eyed beans outside my grandmother’s house, avoiding the stares of village women who squat on their doorsteps, dressed entirely in black. (I now realise these women were, at most, in their fifties, but as a child, they seemed like fearsome, wizened old crones.) I have watched with curiosity as my great-uncle Yusuf slept in a corrugated iron bed in a field in the village my mother was born in. I was a child at the time – we spent every summer until I was nine at my grandparents’ house in northern Cyprus. It seemed to me his bed had landed clean out of Bedknobs and Broomsticks.

Videos by VICE

I have careened around northern Cyprus’s mountainous roads, lurching across the backseat of my grandfather’s car – no seatbelts! – hair wet from the sea, toes sticky with sand. “Look,” my mother nudges me. It is Five Finger Mountain, waving hello like a giant hand. From the front seat, my grandmother hisses: “See how there are no trees? The Greeks burned them down.” Out of the window, I see plunging ravines. My grandfather is a fast driver. I close my eyes and scream. I am an anxious passenger to this day.

My country does not exist. Not according to everyone: Britain, the EU, the world. I wrote “the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus” in an article the other day, and my sub-editor had a stroke. “Sorry,” he emailed. I could feel him cringing. “It’s not in our style guide. I seem to have stepped on a geopolitical hornet’s nest here!” I tried to buy a book recently that promised to tell the story of the “authentic Cyprus”, as it existed in the 1950s, before the island was divided in 1974. I messaged the book’s author to check what percentage of the eyewitness testimonies she’d collected were the voices of Turkish Cypriots. Five percent, she told me. The island was one-fifth Turkish at the time. I didn’t buy the book.

Turkey says my country exists, sure. But who listens to Turkey? To fly into northern Cyprus, you have to go via Ankara or Istanbul. The plane waits on the tarmac in Turkey, before taking off. When it lands, everyone claps. Clearly, not a serious country.

All of this is to say that my country is not real. My country does not exist. My country is a formatting error on a world map. I have known this my whole life. Which is why I unexpectedly found myself crying when I read Yasmin Khan’s Ripe Figs: Recipes and Stories from the Eastern Mediterranean. I’ve rarely seen Turkish Cypriot voices represented in food writing about Cyprus before, even in ostensibly progressive outlets. Most writers use “Greek” and “Cypriot” interchangeably when referring to the food and culture of Cyprus. Turkish Cypriot voices simply do not exist. Khan doesn’t do this. Khan sees my heritage.

“It’s deeply unfair, and unjust,” she says simply, of this ongoing erasure.

Khan is a big-hearted food writer who understands the Middle East in a way that few writers, food or otherwise, seldom do – she has Pakistani-Iranian heritage, and spent a decade working as a human rights campaigner on issues including Palestinian rights and the war in Iraq. In Ripe Figs, Khan writes movingly about the eastern Mediterranean’s border politics, and how it plays out on plates across the region. She travels to the refugee camps of Lesvos, Istanbul and Nicosia, Cyprus, the last divided capital city in the world.

“The camps in Greece,” she sighs, “were so inhumane, and degrading. On EU soil, 19,000 people being held in a camp that fits 3,000 people. Dangerous conditions. Fights, sexual abuse. These were people who had gone through unimaginable challenges themselves.”

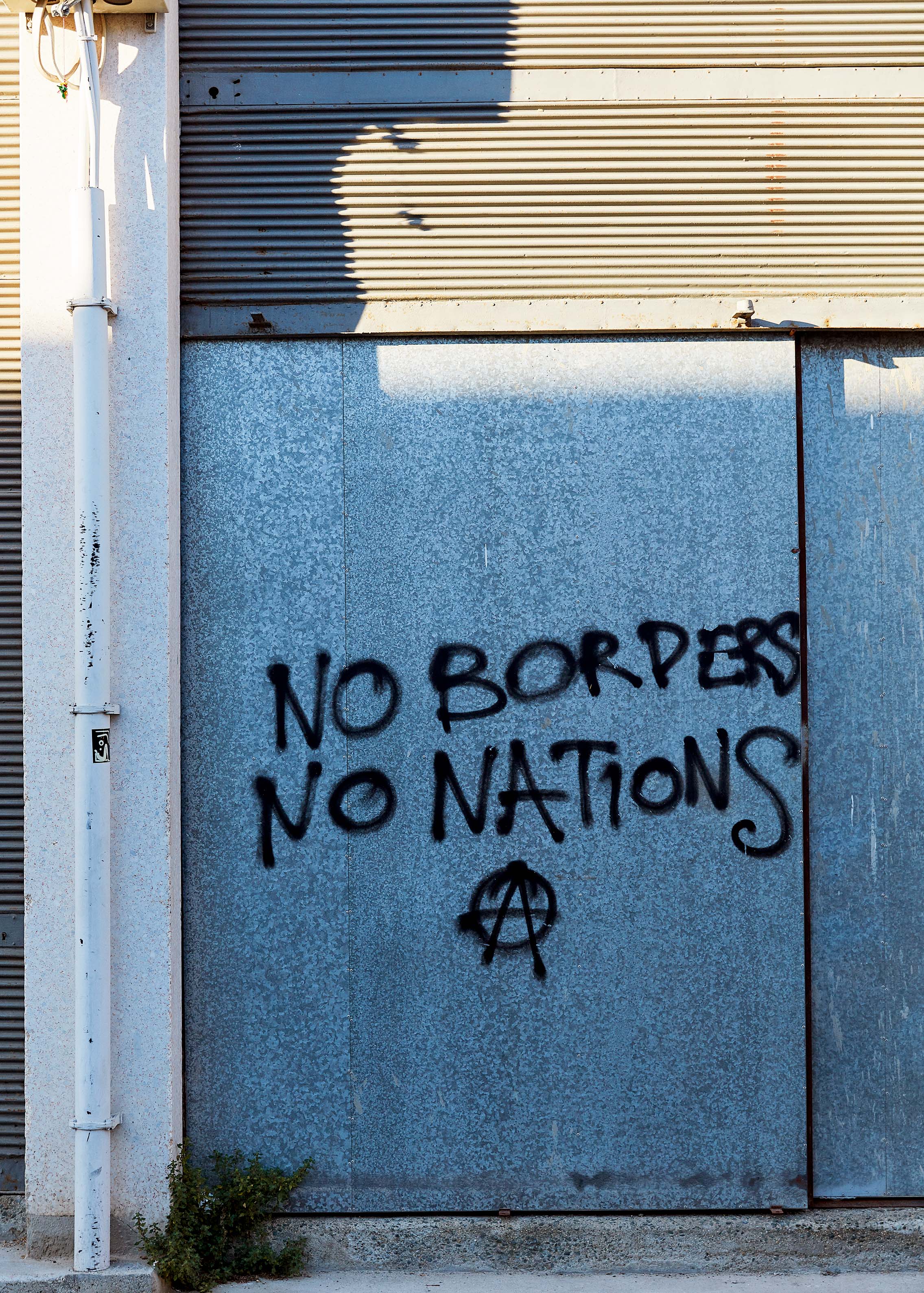

Central to Khan’s work is the thesis that man-made borders are arbitrary, ridiculous and absurd creations, and that the age-old act of sharing food – literally, breaking bread – with those who are different from you is a way to recognise the shared humanity of those whom politicians and ethno-nationalists would prefer you to view as other, or sub-human.

“Cyprus is a microcosm of how man-made borders can divide us where there doesn’t need to be division,” Khan says.

A brief summary of what happened in Cyprus: in the 1950s, Cyprus was a British colony, with about four Greeks to every Turk. Greeks and Turks lived peaceably, side-by-side, in mixed villages. Cypriots didn’t have the franchise or other basic rights, and Greek Cypriots began agitating for independence from the British, and enosis – union – with Greece. The British didn’t want to lose Cyprus, which was a key military and strategic base, and so began exploiting tensions between the two communities as a way of dividing the country, and holding onto it. This didn’t work, as a result of an armed insurrection ran by Greek-Cypriot nationalists, and Cyprus gained its independence in 1960.

But the legacy of this ethnic division remained. Greek Cypriots felt that the island’s new constitution gave an unfair amount of power and influence to the Turkish Cypriot minority, while Turkish Cypriots felt outnumbered and surrounded by Greek Cypriot nationalists who still desired enosis. In 1963, inter-communal violence broke out on the island between the Greek and Turk community, although in truth, it was more of a massacre of Turkish villages and enclaves by far-right Greek nationalists. Turkey threatened to invade to protect the Turkish minority, but was talked down.

In 1974, far-right Greek nationalists overthrew Cyprus’s president, and attempted to annex the island to the military junta of Greece. Fearing a genocide, Turkey invaded the north of the island, to protect the Turkish community. Around 40 percent of the Greek Cypriot population, and half of the Turkish Cypriot population, were forcibly displaced, causing great trauma for both communities. Turks relocated to the north of the island, which stagnated economically, while Greeks moved to the south, which became prosperous. So much heartbreak, all because the British wanted to hold onto their colony. They don’t teach you about that in schools.

“It was really important for me to put that in the book,” says Khan, “because anyone who knows about colonial history knows that happened in quite a lot of places, whether it was Israel-Palestine or Pakistan and India. It was a tactic of British colonialism to stoke ethnic tensions as a way of trying to divide and rule, and hold onto their colonies.”

Khan’s books are a quiet corrective to the anti-intellectual flag-shagging patriotism of today, which sees any attempt to interrogate Britain’s colonial past met with accusations of “cancel culture” by the right-wing press, and legislation proposed by the government that would punish defacing a statue of Churchill more harshly than violence against women.

We are talking while I make Khan’s yoğurtlu patlıcan salatası, roasting the aubergines in the oven before mixing them with yoghurt, garlic, parsley and plenty of good olive oil. Out of all of Khan’s books, Ripe Figs is probably the most accessible: the meals are simple and delicious, and most of them have fewer than six or seven ingredients. This is not Ottolenghi cooking, with an A4 list of expensive, hard-to-find ingredients.

Crossing the border from Cyprus into northern Cyprus, Khan was struck immediately by the contrast between the wealthy, developed south, and the impoverished north. “That economic disparity was what I found the most uncomfortable aspect of it, because it was so unjust and unfair really,” she says. “It feels like you’re going back several decades in terms of infrastructure like roads and buildings and amenities. You can tell that it’s at a huge economic disadvantage. There’s less jobs. Crumbling buildings.”

In northern Cyprus, Khan met Turkish grandmother Nahide Köşkeroğlu, who taught her how to make halloumi and olive bread. “I just wish the island could merge and turn into something different, coming together as an island of Cypriots, because that’s what we all are,” Köşkeroğlu told her.

Köşkeroğlu’s views are shared by the majority of Turkish Cypriots, including my relatives, who voted in favour of reunification with Cyprus in a referendum in 2004. But the Greek Cypriots don’t want to reunite with their northern cousins, rejecting the referendum, nor do they want to recognise northern Cyprus as legitimate. So, Turkish Cypriots are stuck.

“The prejudice I saw in Cyprus from the Greek Cypriot community was very clear,” Khan says. “Of course as a writer and journalist, you only see a cross-section of society. But even the casual ways in which people used language demonised the Turkish community.”

In Ripe Figs, Khan describes meeting one Greek Cypriot woman who feasts her on braised lamb with okra, and tells moving stories of being forcibly displaced as a child, before bitterly talking about how she brings her own food with her when visiting the north of the island, as she doesn’t want to give “them” money, as they shouldn’t be there.

Khan’s work feels especially urgent given that the Institute for Economics and Peace recently predicted that 1 billion people face being displaced due to climate change by 2050. “You know I’m of mixed heritage,” says Khan, “and people like us, we’re the future. My attitude towards nationalism has to become more fluid because I don’t have a linear national identity. It’s such a recent modern construct anyway. Nation states have only really existed for the last few hundreds of years. This idea that we have a crisis around borders is such a weird framing, given that for the whole of human history, our species has travelled for its survival…and with all these climate refugees, that’s not so far away. Unless we start deconstructing what it means to have borders and to make it work in a more effective way, we’re going to have a really dangerous future.”

Aubergines cooled, I mix them into the yoghurt sauce, and spoon it directly from the bowl. Over Zoom, Khan does the same. The garlic and parsley combination, a staple of Cypriot cuisine, feels as familiar as a hug. It takes me back to those endless summers in Cyprus. When I was a child, we’d pick jasmine flowers from the bushes outside my grandmother’s village house and sit in plastic chairs, slapping mosquitoes from our legs. My sisters and I, we’d thread the flowers onto white cotton, to make bracelets. We’d fall asleep in those uncomfortable chairs, and wake up in bed the following morning, wrists sticky with mildewed scent, crushed flowers staining our bedsheets yellow.

The scent of jasmine. It is the scent of home, the scent of my people, the scent of my childhood. The scent of my country.