“We’re going to War,” Paula Jean Swearengin announces with a chuckle as we dip around winding roads in the thick of the Appalachian Mountains. She’s talking about War, West Virginia—population 862—but she might as well be talking about herself.

After a decade-plus as an environmental justice activist deep in coal country, the 43-year old single mother of four is running for US Senate against incumbent Joe Manchin, a former governor who is the chamber’s most conservative Democrat. Her run comes at perhaps the Democratic Party’s lowest point in West Virginian history. The onetime Democratic stronghold was won by Donald Trump by 42 points last year, Democrats lost control of both houses of the state legislature in 2014 after decades in power, and the state’s billionaire governor, Jim Justice, announced at a Trump rally he was going back to the Republican Party after being elected as a Democrat.

Videos by VICE

This movement toward the GOP comes amid the decline of coal, which has devastated the state’s economy. With many national Democrats highlighting cleaner energy sources and catering to a base that mostly lives in big cities, it’s no surprise that West Virginians would look elsewhere for leaders—especially with Trump explicitly promising to bring coal jobs back.

“People kind of see their communities not as vibrant as they once were,” West Virginia University professor of political science Patrick Hickey says. “It’s just a very simple calculation.”

Swearengin hasn’t been given much of a chance against her much better-known, better-funded opponent. “It’s like David versus Goliath if David didn’t have a sling or a rock,” says Walt Auvil, a former county Democratic Party chair who ran for the state party’s leadership in 2010.

But Swearengin and her supporters hope that by running on a left-wing populist platform that stresses economic and environmental justice, they can turn back the tide of red that’s swept over the state. It’s a stark contrast to Manchin’s middle of the roadism, and the gamble is that voters aren’t ideological conservatives so much as they are frustrated with the results of centrist Democratic control.

It gets at the heart of a larger question that liberals all over the country are trying to find an answer to: Can progressives save the Democratic Party in red states? “This is a chance for an FDR Democrat to take the party back,” says Charlotte Pritt, a Democrat who handed Manchin the only defeat he’s seen in his political career in the 1996 gubernatorial primary (she lost the general election that year). “And it’s really the only chance the Democratic Party has left.”

West Virginia was born from conflict. When Virginia seceded from the Union at the opening of the Civil War, the anti-slavery western counties of the state rejected secession and formed the Restored Government of Virginia, with Wheeling as the capital. In 1863, West Virginia was admitted to the Union.

After the Civil War, coal became West Virginia’s biggest economic export. In West Virginia and other places around the country, coal mine operators heavily exploited the labor of miners, who eventually organized themselves to fight for better wages and living conditions. It all came to a head at the Battle of Blair Mountain, a five-day armed uprising in Logan County that has become one of the most famous labor conflicts in American history. It was there that miners fought the Logan County Sheriff, Don Chafin—who would later become an influential Democrat in the state—and a private militia. By the end, somewhere between 20 and 100 people were killed, and almost a thousand miners were arrested.

After the stock market crash in 1929 and the beginning of the Great Depression, Democrats took control of the House of Delegates in 1930 (and the state Senate two years later) and didn’t let go for 84 years. “The Democrats had a political monopoly to provide goods and services to people and people appreciated that,” Hickey says, pointing to infrastructure all over the state that bears the name of longtime US senator Robert Byrd. “And [now], there’s this odd disconnect where people don’t really think that the Democrats are taking care of them anymore.”

Democratic candidates know the party’s brand is badly damaged; Swearengin speaks of her disdain for “labels,” as does Huntington mayor Steve Williams, who was a vocal Clinton supporter and is running for Congress next year in the southern Third District. “I think we make way too much of D vs. R,” Williams says. “Let’s just focus on WV and make sure that we’re creating opportunities for people to have jobs and take care of your families.”

With the GOP taking over the state government, Manchin has remained the last Democrat standing (West Virginia’s other senator and three representatives are all Republicans). Manchin became governor in 2004, then won a special election to replace Byrd in 2010. Despite the D next to his name, Manchin will never be mistaken for a liberal: He’s disagreed with his party’s positions on healthcare and climate change, he was one of the last Democratic senators to oppose same-sex marriage, he was resolutely pro-gun until the Newtown shooting, and remains personally pro-life. After his primary loss to Pritt in 1996, Manchin threw his support behind her Republican opponent.

As Democrats’ influence in the state has waned, the conservative Democrat’s power has only waxed; a poll released last month showed he was the most popular politician in the state, beating out even Trump. He also has a sizable lead over his prospective Republican challengers.

His profile has grown in the Senate as well, where he’s become a crucial swing vote. He was one of four Democrats to vote for the repeal of an Obama administration stream protection rule, and he voted to confirm the nominations of both Jeff Sessions for attorney general and Neil Gorsuch for the Supreme Court. Multiple times since Trump’s election, Manchin has been rumored to be a possible Cabinet pick for Trump, rumors he has repeatedly shot down. (Manchin’s office didn’t respond to numerous requests for comment, and emails forwarded to state Democratic Party chair Belinda Biafore, a Manchin ally, were not returned.)

To understand the Democrats’ precarious position in the state, you have to understand the rough circumstances that many West Virginians have found themselves in, which all seem to be traced back to coal. At peak coal employment in 1948, there were an estimated 125,669 miners in West Virginia; this year, according to a report from Huntington TV station WSAZ, there were 11,402 in the first quarter of 2017. Still, the industry has an outsized influence on the state’s politics because for many it’s the only type of employment that provides a livable wage.

The coal industry made it possible for many families to survive and prosper; at the same time, it has reshaped the state’s landscape and saddled residents with health problems. As the industry declines—thanks in large part to fracking—West Virginia’s economy has become unmoored, with tragic societal consequences. The state GDP shrank in 2016, and even though its workforce is the least educated in the country, the Republican legislature recently cut the higher education budget. The nationwide opioid epidemic has been felt acutely by West Virginia, which has the highest overdose rate in the country.

To this day, Swearengin deals with stomach problems that she suspects can be traced back to drinking “poisoned” water.

Driving around the small community where she lives in a modest trailer, Swearengin recites the stories of people she knows: retired miners with terminal illnesses, young parents who are either struggling with an opioid addiction or are on Suboxone. “Someone shot somebody in the face here,” she says, tapping her window and pointing at one house. “This is a really big drug-ridden neighborhood down here. Sometimes you can come up in here, and it looks like an episode of the Walking Dead.”

Swearengin was born in Mullens, West Virginia, and grew up in Iroquois before her family moved to North Carolina when she was 12. Growing up, she says, her family’s water was orange with a blue or purple film; her mother, Helen Shrewsberry, adds that sometimes it had “black, oily stuff” in it as well. “[My kids] lived at the pediatrician’s office,” Shrewsberry says. “They couldn’t breathe… they took medicine all the time.” To this day, Swearengin deals with stomach problems that she suspects can be traced back to drinking “poisoned” water.

Her trailer in Coal City is less than five miles from a mine owned by Justice, the governor, and she says that she and her children—her youngest is a junior in high school—breathe silica dust from the mines. The election sprung her into action. “When I saw Jim Justice become my Democratic governor,” she says, “and once Donald Trump won, I thought that anybody could run for office.”

Swearengin’s start in environmental activism came around “2003 or 2004,” she says, when she lived in the nearby town of Lester, and an alarming number of her neighbors were diagnosed with cancer. At one point, she says, she counted eight houses within two blocks where people were suffering from the disease.

After researching, she found out the cause could be traced back to coal mining, in particular “slurry,” residue from the coal-cleaning process that’s injected into empty mine shafts, where it can ultimately contaminate groundwater. That contamination can in turn cause cancer and a condition that one West Virginia University professor called “‘slurry syndrome,’ a mixture of diarrhea, rash, some changes in their teeth, and increasing frequency of kidney stones.”

Swearengin then learned about mountaintop removal, which is pretty much exactly what it sounds like: Coal companies literally blow up the tops of mountains in order to mine the coal underneath. The process, like slurry injections, has been linked to a multitude of health issues.

“I just got madder than hell,” Swearengin says. “And I didn’t know what to do, so I started going to anyone who would listen to me.”

Since then, she’s worked with different environmental groups around the state and has repeatedly challenged the state’s politicians, including Manchin. In March, she drove to South Charleston for a town hall Manchin hosted to confront him about clean water. She didn’t have the cash for a toll, Swearengin’s friend Lisa Henderson says, so she left an IOU with the booth attendant.

Her environmental activism has been hard at times. She says she had three jobs in 2012 after shaving her head in a protest at the capitol in Charleston. One of those jobs was as the manager of a doctor’s office; the staff began to show up to work wearing pro-coal shirts after they found out she was an environmental activist. “One came in with a shirt that said ‘Shoot a Treehugger, Save a Coal Miner,’” she says. “I even had some of my patients pissing on my car… I’ve had my life threatened. I’ve had people tell me they would come after my children.”

Swearengin wants an end to both mountaintop removal and fracking—which many see as a potential economic boon for West Virginia—as well as stronger environmental and safety regulations on the coal industry. After eight years of talk about the “war on coal,” an unabashedly pro-environment position hasn’t been especially popular here; Democrats’ vote share in the presidential race fell from 43 percent in 2008 to just 27 percent last year.

Still, Swearengin thinks she can win over people who might otherwise be resistant to her approach on coal by running on a Sanders-like economic message. Her platform reads like a to-do list of progressives all over the country: a $15 minimum wage, Medicare for all, universal pre-kindergarten, free public college tuition, and a massive investment into infrastructure.

It’s obvious, however, that coal will be her biggest hurdle. Swearengin plans to counter that talking about clean energy and infrastructure (she touts the potential of wind and solar) as a way to produce jobs, and diversifying the economy beyond the energy sector. She points to legalizing marijuana as a short-term solution for West Virginia’s economy, as legal pot has been proven to boost tax revenues in a big way. Still, she knows there are people who can’t get over her opposition to coal, the real third rail of West Virginian politics.

“It scares me,” Shrewsberry says of her daughter’s campaign and the threats she’s received through her environmental activism. “People here used to disappear.”

Her mother’s fears aren’t entirely unwarranted. I meet Swearengin and a man with a crew cut outside of a Mexican restaurant in Beckley, the seat of Raleigh County and one of the larger towns in the impoverished southern part of the state. “Senator Richard Ojeda,” he greets me with a handshake. “I’m the one that almost got killed last year.”

Ojeda isn’t joking. In May 2016, he was brutally beaten within an inch of his life at a campaign event by a childhood friend. He thinks it was a politically motivated attack on behalf of his opponent, Art Kirkendoll, a powerful former Logan County commissioner who was appointed to the state senate in 2011. “I can’t say that [Kirkendoll] was behind it,” Ojeda says. “But I can say that people who supported him were behind it. It’s the Wild West in some of these areas.” (Kirkendoll has denied any involvement in the incident; Ojeda’s attacker pleaded guilty and was sentenced to one to five years in prison.)

Ojeda, who is running for Congress next year against Williams, the Huntington mayor, is a political anomaly. At times, he sounds like a progressive Democrat—he helped get West Virginia’s medical marijuana law passed and has strong, dovish opinions about the nature of war. “When the rich wage war, it’s the poor who fight and die,” the veteran of Iraq and Afghanistan says, jabbing his finger into my shoulder to drive his point home.

Last year, however, Ojeda—whose father’s family hails from Mexico’s Pacific coast—spoke glowingly of some of Donald Trump’s hardline immigration positions. “When you start talking about bringing in refugees and when they get here they get medical and dental and they get set up with some funds—what do we get?” he told the New Yorker before the election. “So when people hear Donald Trump saying we’re going to take benefits away from people who come here illegally and give them to people who work, that sounds pretty good.”

“During the primary, I noticed that even the Republicans didn’t like this guy, and he was the one speaking about West Virginia,” Ojeda tells me of Trump. “And we haven’t had anyone speak about us since [John F.] Kennedy… Everybody around here, we have one thing and that’s coal. And when coal is down, our people are starving. That’s why it was so important.”

When someone like Trump says he wants to bring back coal, Ojeda explains, “People—even if they know it’s probably not going to be true—they just want to believe something.”

Ojeda doesn’t think so highly of Trump now. Both the culture of nepotism in the White House and the president’s tweeting irk him. But his prediction that Trump would win big came true: The Third District, statistically one of the poorest in the country, voted for Trump by a margin of almost 50 points. Trump won every county in West Virginia; Hillary Clinton didn’t win a county in the primary against Bernie Sanders either.

“The last time I saw Joe Manchin, he treated me like I had the plague.”

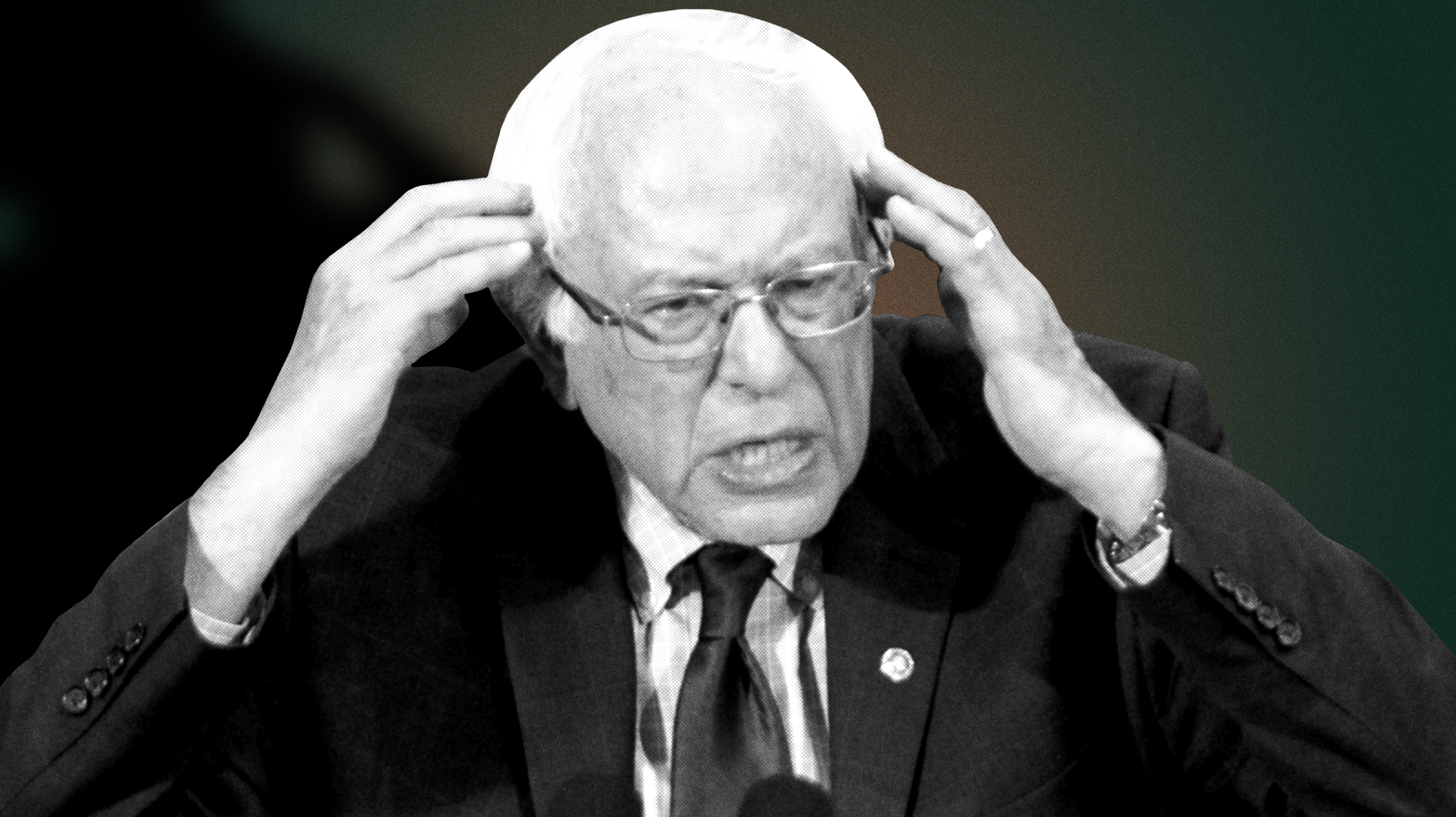

That primary result provides a sliver of hope for Swearengin, who was inspired by the campaign to register as a Democrat just so she could vote for Sanders. “Everyone in West Virginia loves Bernie,” she says.

In March, Sanders took part in a town hall with MSNBC’s Chris Hayes in McDowell County. Swearengin went, and after the event was over, asked Sanders if she could speak with him; at the end of their conversation, they hugged. To this day, she’s still touched by the gesture.

“He sat down and talked to me like I was a human being,” she says, growing emotional. “The last time I saw Joe Manchin, he treated me like I had the plague. And Bernie Sanders, a senator from Vermont, came here and cared about me more than our leadership ever has.”

Though Sanders and Trump don’t have much in common politically, Swearengin thinks that they appealed to West Virginians in a similar way. “People were desperate for jobs,” Swearengin says. “We’re one of the sickest and poorest states in the nation. Bernie Sanders came in and offered solutions. Donald Trump came in and offered jobs.”

Others note that both men looked appealing to West Virginians in comparison to Clinton, who was linked to her husband’s NAFTA legacy and her own initial support of the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Clinton also suffered from a widely circulated soundbite where she said that her policies would “put a lot of coal miners and coal companies out of business.” (Her next line, usually omitted in attack ads, was, “And we’re going to make it clear that we don’t want to forget those people.”)

“I think [Sanders’s primary win] probably has more to do with the fact he wasn’t Hillary,” says Jeff Kessler, a former Democratic leader of the state senate and one of last year’s Democratic gubernatorial candidates who endorsed Sanders. But Kessler also thinks Sanders regenerated the Democrats’ long-dormant progressive base, one that Swearengin will hope to capitalize on next year.

“Bernie appealed to a lot of younger folks and even the progressive wing of the party, which felt like they had been ignored by the party for the last decade,” he says. “You learned in the conservative Joe Manchin school of West Virginia thought that you were irrelevant.”

Auvil, the former Democratic county chair, thinks that Swearengin is a long shot to win her race against Manchin. But he believes that the common wisdom among Democrats—that a progressive can’t win a general election in West Virginia—is short-sighted.

“I think there’s a lot of folks who would say that the realpolitik of things is that Joe Manchin and Jim Justice are the best we can do,” Auvil says. It’s true that the state party has been run by centrists, but those same centrists have lost power to the Republicans. “[Pritt] was the last proudly progressive [gubernatorial] nominee, and who was responsible, in large part, for Pritt’s defeat? Joe Manchin.”

“The Democratic Party has a great opportunity to field candidates like Paula Jean, [First Congressional District candidate] Mike Manypenny, and Senator Ojeda,” Pritt says. “And those three people—they will be the side for the people. They are all fighters.”

“I never wanted to do this,” she says, which is a refrain you often hear from first-time candidates. But in Swearengin’s case, you get the sense that she means it. She’s spent years fighting as an activist and lobbying Manchin and other West Virginia officials to adopt her positions, and she even says she was forced out of her job as an accountant’s assistant; her bosses cut her hours after she decided to run, according to a Justice Democrats fundraising email from July.

Sanders’s win in the primary and the adoption of one of the most left-leaning state platforms in the country show that the progressive base of the Democratic Party here just might have some fight left in it. That attitude could remain after the next election cycle. Activists here speak glowingly about the increase in engagement they’ve seen since Trump’s election, especially from young people.

But Swearengin faces a serious deficit of name recognition and money against the well-funded Manchin. If she’s able to garner 35 or 40 percent of the vote in next year’s primary, it’d be a moral victory. Beating him would be one of the biggest upsets in American political history.

Some liberals, looking ahead, worry about Swearengin winning a general election, but Kessler disagrees. “If she can beat Joe Manchin, she can beat any of those other fellas,” he says, a reference to the top two Republican candidates, Congressman Evan Jenkins and Patrick Morrissey, the state’s attorney general. “There’s no question.”

But first, she’ll have to take on the Democratic machine here and the most popular politician in the state. And given her history of environmental activism and the attack on Ojeda last year, it’s been natural for her family and friends to worry about her safety.

Swearengin says she reminds her mother that she’s in danger for other reasons. “What I tell my mother is that, because of where we live, they’re going to kill us anyway,” Swearengin says, voice shaking with anger. “They’re going to kill us anyway. If it’s slowly or quickly, they’re going to kill us… I have given my life to the coal industry, and I’ve sacrificed enough. And they cannot have my children.”

Update 9/7: An earlier version of this article confused the names of the towns where Swearengin was born and grew up.

Paul Blest is a contributing writer for the Outline and Facing South. He lives in Raleigh, North Carolina.