This weekend, Stormzy’s “Wicked Skengman Pt4” freestyle will chart in the Official UK Singles Chart, the latest in a string of commercial victories for British urban music with Skepta, Krept & Konan, Fekky, Stormzy and more all finding global recognition. But when one sound become this emphatically popular, does it also provoke negative connotations for those that aren’t a part of it? If there’s an emerging black British artist who does not consider themselves grime, hip-hop, or even urban, then are they put at a disadvantage?

Up in Manchester, I’m sat with four musicians – Bipolar Sunshine, Jazz Purple, Gaika and August&Us – who, alongside a further network of creatives, have set up a collective that makes music, art, and events, and challenges the frustrations of being a black artist that operates outside of genres that they have come to be expected to fit into. Their name: GREY.

Videos by VICE

“I was finding that I was considered too ‘urban’ to be played with any real frequency on XFM, but too ‘indie’ for Radio 1Xtra,” explains Bipolar Sunshine, real name Adio Marchant. “We were trying to stand alone with a certain sound, but instead being put into the ‘indie nigga’ category without people really bothering to take a close look at what we do. They just see a black guy near a guitar and put you in that lane.”

Together, in a shared studio in Manchester’s Northern Quarter, adorned with collages upon collages of artwork that inspires them, GREY collaborate, share ideas and work hard on their shit. The melancholic, psychedelic soundscapes of each of the artists range from alternative pop all the way to electronica, while their lyrical content deals often with existential issues such as hedonistic guilt, the breakdown of family and romantic relationships, and issues of identity politics. They are, in all respects, relatable and interesting artists, whose work is both sonically and lyrically accessible, and has been played on Radio 1 in the past. So why do they feel like they are swimming against a tide?

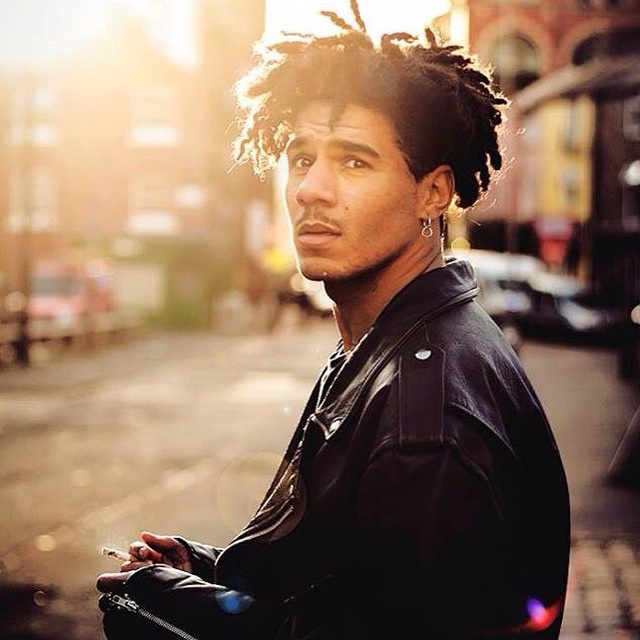

Pictured: Jazz Purple. Photo by Sam Pyatt.

GREY member, director, rapper and visual artist, Gaika, has his own opinion on the matter. “Black music in Britain is defined by those on the outside, that’s the first problem. So, black music in Britain gets defined vaguely as club music. Anything with a strong live element that isn’t directly identifiable as rap, grime, or homeland music, is deemed unplaceable: ‘experimental’ niche music that will never make any money for the fat cigars. Maybe it’s because a financially successful precedent hasn’t been set in the post-Napster era, or maybe, just maybe, it’s because the old white men who run the industry aren’t quite ready to let go of their desire to recreate every musical reality in their image. I mean, where are all these successful black indie bands lurking?”

Continues below

The source of the problem, in the GREY collective’s opinion, rests firmly with the establishment. “If you look at things like the MOBO Awards, they are meant to be music of black origin, but they don’t celebrate the change in British culture anywhere beyond London,” says Bipolar Sunshine. I ask if the fact that the MOBOs have been held in Glasgow for the last six years makes a difference, and he shakes his head. “In my opinion they celebrate the wrong things, or, better still, broadcast what they want the nation to believe is black culture. That’s just bullshit though – black culture is a lot broader than that.”

Gaika’s take on it is a lot less compromising. “1Xtra and the MOBOs can suck a dick. Their relevance is rapidly diminishing because they almost exclusively push a hugely simplistic retrograde view of ‘urban’ culture that lacks the ability to self define. Those gatekeepers need a good shake. How can it be that we’ve all had way more support from Radio 1 and sometimes XFM, than 1Xtra? It’s like they’re literally telling us the music we make has no place in ‘black culture’ – but I don’t think that the mandem in the street, black or white, think like that at all.”

Pictured: Bipolar Sunshine. Photo by Sam Pyatt.

The collective’s words ring true when you consider the diversity of the crowds that come out to see Bipolar Sunshine, from SXSW to Glastonbury, not to mention him being offered support slots for acts as wide ranging as A$AP Mob to Stone Roses. Still, despite his early success, his label Polydor wavered with where to place him and his recent tour went ahead with little support from them. Despite that, he still managed to culminate it with a lit London show and a sold out homecoming Manchester gig.

But despite having potential, artists like Bipolar Sunshine, Jazz Purple, Gaika and August&Us, are often denied the support and investment they deserve. “I feel like if I make anything that doesn’t neatly fit into stereotypes, then the people making marketing decisions can’t handle it,” says Bipolar Sunshine. “They think that the ‘urban’ market (of which they have zero knowledge) has underdeveloped palettes and won’t understand something, or they think the white pop/rock market is hugely conservative and won’t like it either.”

Of course, there are still stories of encouragement. You don’t need to look far to find game-changing acts like FKA Twigs and Young Fathers showing that they can become successful on their own terms, despite the hurdles in place. Gaika nods tentatively, “It’s yet to be seen how big labels can monetise this kind of boldness on the grandiose scale they are used to. These acts remain the anomalies as opposed to the rule.”

Pictured: August&Us. Photo by Jac Frederick Rudduck.

Adio laughs, “For us, our accents really don’t help with the confusion. They’ve never heard the voice of black Mancs being able to deliver a message without it being UK rap or grime.”

Making music which resists being pigeonholed is all well and good, but how, without the proper support they seek, can they feasibly be successful on the scale to which they aspire? “The artist holds power,” Gaika says. “At the end of the day it’s our work. I guess we are trying to show people that. You can make music that a lot of people like without doing some kind of pathetic Faustian dance with some public schoolboy tickling your balls.”

How far GREY will go in changing the way people understand the broadness of black British music though is yet to be seen, but they are wholly positive and determined. “A lot of shit has gone on in our lives and we are finding ways to discuss it through our music. I feel like we are pushing something that isn’t just about Manchester but the world. We come from a place that has a history of creating new scenes that become the cultural norm. Manchester has done this on many occasions and we are about to do it again.”

Follow Kamila on Twitter.