(Picture via)

Brixton is often held up as an exemplar of how to “regenerate” a destitute metropolitan area. It’s the end result of a concept taught the world over by careless urban planning lecturers: build a city’s first ever vegan cupcake boutique and people – the “right” people, crucially, the kind who will drive up property prices by filling the streets with prams rather than gangs and friendly looking labradors rather than weapon dogs – will come. And come they have, flocking in their droves and pushing up rent PCMs to the point where local families can’t afford to live in the neighbourhood they grew up in. But at least they now have speedy access to Brixton Village’s kumquat smoothies and hand-crafted homeware, which has to soften the blow a little.

Videos by VICE

That same kind of thing is now happening all over London – and, in fairness, it’s been happening for decades. But in this age of austerity, where more and more people are being sucked out of their homes and spat into the poverty gap, are there any signs that people will stop the process of gentrification in its tracks?

Last month, somebody wrote “YUCK” on the window of a new Foxtons Estate agent, which was presumably directed at the young professionals looking to buy homes in the area, rather than that disgustingly lame thing Foxtons do where they try to make their offices look like Soho cocktail bars. Then, just to clear up any confusion, someone wrote, “YUPPIES OUT!” on the same window – an unambiguous pop at the posh interlopers.

Photo by Jake Lewis.

The people of Brixton held a party on the day of Margaret Thatcher’s death, which is kind of fitting, considering the changes to the area are basically a direct product of her political legacy. Thatcher’s fans tend to cite the 1980 “Right to Buy” Housing Act – which allowed council tenants to buy their homes at discounts of up to 50 percent off the market price – as the single best policy made by any politician in the history of the world. But while it meant that a lot of people could afford to buy their own home for the first time, it also created a gaggle of new private landlords, meaning stocks of affordable, council-owned accommodation were depleted.

Subsequent governments didn’t bother reversing any of this. For instance, Tony Blair did his bit to accelerate the process of what he called “transferring” council houses to the private sector, which is essentially just what Thatcher did, but using a different name to distance himself and the Labour Party from the woman his voters were raised to despise. This apparently wanton sledgehammering of social housing and an increasingly expensive housing market have left a generation floating in private-rental purgatory.

The stats speak for themselves: Over the past decade alone, the price of the average home has increased by 94 percent, while wages have risen by just 29 percent. And rent is set to increase twice as fast as house prices in 2013, according to the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors. If that all sounds a bit abstract for you, the real-life consequences are revealed by new figures from Shelter, which show that 3.9 million British families may be just one pay cheque away from losing their family home. The results of that are borne out in the National Housing Federation’s latest report, which suggests that homelessness has risen 26 percent in two years.

If those figures aren’t depressing enough, here’s some more bad news: things are only set to worsen with the recently introduced set of austerity measures, such as the bedroom tax and housing benefit cap. High demand for accommodation in the city means that London feels the effects of the measures more intensely than the majority of the country, meaning the gentrification that’s already forcing people out of their homes will receive a boost in the form of George Osborne’s penny-saving tactics.

In fact, the housing shortage in London is so chronic that councils are threatening to move people languishing on housing waiting lists to places like Margate, which is both an employment blackspot and somewhere you probably don’t want to move if you’re used to the luxuries that London affords. Luxuries like being privy to a bus service that runs more regularly than every 25 minutes, or living within a reasonable distance from everyone you know and love.

Various groups have sprung up to protest the forcing-out process – some manned by keyboard warriors and others, like Yuppies Out, run either by school children who have just discovered politics and the caps lock button, or a right-wing genius satirising Britain’s mass of morally-outraged but physically inactive liberals.

There’s no direct resistance group making waves in Brixton just yet, but – culturally speaking, at least – John Major’s home borough seems pretty emblematic of the ongoing problem. So I headed there to find out if the anti-Foxtons graffiti was an infantile piece of petty vandalism or a sign of genuine disaffection bubbling beneath the surface.

When I got there, I met Nikki Bling, who suggested that gentrification could harm the vibrancy of London by destroying working class culture and roots and replacing it with bourgeois banality. “Keep Brixton fucking ghetto!” she asserted. “These people made this place, and when yuppies come in, they’re just going to try and take over. The ghetto is where all the style comes from. They follow our style, our swagger, everything, you get me?”

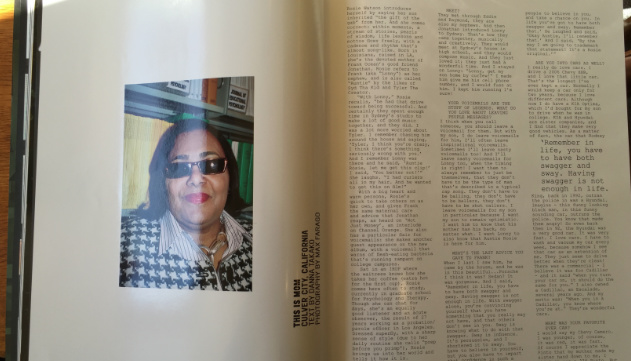

Market trader Jeff Organic, pictured on the left here, was pretty sanguine about the changes, pointing out that Brixton was basically broke before what he termed “the ‘so-called’ gentrification”. Jimmy on the right wasn’t so upbeat, saying, “In years to come, it’s going to be like Paris, where the whole of central London will be money and everyone with less money will be pushed to the outskirts.”

He continued: “It’s sad. London used to have character – east was completely different from west and each different area had its own vibe. Now, no matter where you go, it’s the same.” As for the graffiti, he said it was understandable, but told me that vandalism – however artful it might be – isn’t going to make much of a difference. “It’s clear as day what’s happening,” he said. “You can shout and scream as much as you want, but you’re still getting pushed out eventually – end of.”

After visiting Brixton, I spoke to Dr Stuart Hodkinson from the University of Leeds – a man who’s written more academic papers on gentrification than you can shake a gated community key fob at. He agreed with what Jimmy had said, but added a pinch of context, noting that “there is still a large amount of social housing in London that’s affordable – there are enclaves all over the city”. He also told me that different local authorities won’t necessarily plan in a uniform way, meaning that London’s various boroughs have differing (and potentially better) plans for the future of their social housing.

Southbank skate park, another potential victim of the gentrification of central London. Photo by Paulius Ka.

Having said that, he continued, “people on housing benefit will increasingly be unable to rent even social housing in London because the housing benefit will not cover the rising social housing rents. Unless those people magically find a well-paid job, they will be priced out of large parts of London within the next few years.

“But the real issue is that local councils can demolish their social housing stock,” he said. “That means they can open up investment in new social housing, which will be charged at around 80 percent of market rent, whereas existing social housing is charged at 50 or 60 percent of the market rent. So, you get the total demolition of social housing replaced by expensive private housing, and then this pathetic thing of new ‘social housing’ with 80 percent ‘affordable’ rent – which, obviously, isn’t affordable at all.”

Increasing the cost of social housing by 30 percent doesn’t seem like an initiative aimed at those Londoners currently struggling to make rent. I guess that’s what happens when local authorities are deprived of cash from central government and need to make up their own budget deficits. They’re earning more cash by hiking up rent across the board and selling off land to private developers. “They have an in-built bias in favour of gentrification,” Dr Hodkinson told me.

An anti-gentrification banner hanging from a squatted building in Elephant and Castle.

This is exactly what’s happening in Elephant and Castle, south London. Thanks to much of the area being the product of a 70s planning nightmare so bad its architect reportedly committed suicide after its completion, getting around is a bit of an issue.

You’ve got the choice of either dodging a constant stream of traffic on the busy road, or holding your breath for as long as possible so you don’t inhale any noxious urine gases while you try to find your way out of the labyrinthine subways. Few would disagree that changes need to be made in the area – that it should be regenerated, essentially – but the council seem to be tackling the problem of poverty by just sending the poor away.

The brutalist Heygate Estate is earmarked for demolition so that this poverty-cleansing vision can be realised. Adrian Glasspool is the last remaining resident of the estate and refuses to budge. His neighbours have been moved on, often against their wishes, and their “right of return” agreements expire in 2015 – a year before the first new homes are completed on the estate. So, if they do want to return, they’ll have to wait around a while to actually have a house to return to, and such a small number of those houses will be affordable that few will ever be able to come back anyway.

Adrian explained the situation to me: “Analysis shows that, at the end of the regeneration, there will be just eight percent social housing in the whole area. The Heygate Estate was 1,100 social rented homes. They’re going to be replaced by just 79 social rented housing units out of around 2,500 new flats. It’s not producing the mixed community that was envisaged.”

A section of the Heygate Estate. (Photo via.)

Adrian pointed out that the local council had led the charge in unfairly discrediting the estate to gain support for its demolition: “One of their press releases said unreservedly that the bad design of the estate resulted in crime and antisocial behaviour, which is far from the truth. We’ve dug out the crime statistics for the estate, which show that the crime rate was half the borough average.”

That, and the fact that the council has rented the estate out as a set for violent films like Attack the Block, ensured its infamous reputation as a sink estate. Which – according to Adrian and some other locals I spoke to – isn’t really deserved.

The council sold the estate to developers Lend Lease for a mere £50 million – just £6 million more than it cost them to move residents, and an absolute steal for 23 acres of central London. To put it in perspective, an adjacent one-acre site was recently sold for £10 million. So the good people from Lend Lease could have been forgiven for cracking a celebratory Moet as the deal was struck.

The people’s kitchen inside the Elephant and Castle squat.

The 35 Percent Campaign aims to make 35 percent of new housing in Elephant and Castle affordable. It has had some success in stopping the developers getting away with their initial proposal to build absolutely zero in the way of social housing. Nevertheless, the vast majority of the swanky apartments being built will be largely out of reach to the displaced former residents of the council estates.

It is for this reason that a bunch of squatters under the banner “Self Organised London” recently took over a large commercial building in the area, called Eileen House. They used the six weeks before they got booted out to call bullshit on gentrification, hold meetings and cook free food for the locals. One of the squatters, Emma, told me, “Gentrification is not a question of bad yuppies who are the ‘enemy’. It’s about fundamental social, economic and cultural inequalities. It’s the people who don’t have anything in the first place who get thrown out – it’s social cleansing.”

But a quick flick through the history books tells us that, if it takes off in a more serious way, tenants organising themselves can fight their corner. For example, nearly a century ago, 30,000 Glaswegians went on strike to protest against rising rent, forcing the government to freeze rents for the duration of World War One and to pass the Rent Restriction Act of 1915, which lasted until the 1980s. And, besides that often glossed-over piece of British history, there are plenty more examples of successful rent strikes taking place in different cities throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, from Leeds to Milan to Harlem.

There’s nothing quite that serious being proposed in the UK at the moment, but maybe recent chants of “Can’t Pay! Won’t Pay!” on bedroom tax demos could turn out to be a genuine threat of non-payment rather than poll-tax riot nostalgia. As for private renters, a bunch of them known as “Let Down” (with a pretty clever name) are organising to protest against sky-high rents.

None of this is going to give developers sleepless nights quite yet – if they’ve learned anything from history, it’s that local and national government tend to be on their side. But perhaps we’re starting to see the beginnings of a movement opposed to the idea that inner London should be have the same social make up, pricing policy and attitude as Mahiki.

Follow Simon on Twitter: @SimonChilds13

Additional research by Alon Aviram.

More stories from London:

Reasons Why London is the Worst Place Ever

A Girl’s Guide to Looking Like You Live in London

Watch – What Does London Think of VICE?