This article originally appeared on Noisey Canada.

Beyoncé’s a performer. That said, she’s invited us to watch her get free in “Formation” but she also needs us to witness—to “get” it; to get her as an artist. What we’ve witnessed, with the release of “Formation,” is a master class in how pop artists can clearly articulate political views that differ from the mainstream without being labeled didactic and marginalized by the media. And “Formation” couldn’t be quietly relegated to the ether of the internet because it’s such a good pop song. Its mainstream trap beat is skillfully created by producer Mike WiLL Made It; the lyrics, co-written with Rae Sremmurd’s Swae Lee, provide just the right amount of braggadocio, sex, and cute one liners; the looks, styled by Shiona Turini and Marni Senofonte, got the attention of bloggers, and the video direction by Melina Matsoukas delivers just the right artsy-pop-documentary feel.

Videos by VICE

“Formation” is a notably complex meditation on female blackness, the United States of America, and capitalism. And the blackness that this song and video articulates is not some kind of abstract, cool, costume that can be put on and taken off at will. This female blackness is specific.

It’s “My daddy Alabama, Momma Louisiana / You mix that negro with that Creole make a Texas bama.” It’s 26 brown-skinned black women of multiple shades and shapes dancing in step. It’s dark basements and large mirrors where queer black male hips twerk and revel. It’s sun aversion, high collared dresses, corsets, and spread thighs. It’s Messy Mya’s voice from the grave asking what happened to New Orleans. It’s black women’s braless breasts bouncing in hallways lined with bookshelves and brocade. It’s homes underwater because 11 years ago Hurricane Katrina broadcasted to the world that systemic and institutionalized anti-black racism was still state-sanctioned and real. “Formation” is Big Freedia, the queen of bounce music, announcing on behalf of Beyoncé and herself that, “I did not come to play with you hoes / I came to slay, bitch.” It’s Gucci Spring 16, Chanel pre-fall, vintage, and custom clothing. It’s declarations of the coming of a black Bill Gates. It’s a breadth of black cosmologies that means that worship happens on streets, verandas, floats, churches and parking lots. “Formation” is blue hair, piercing eyes and rows of snatched wigs for sale. It’s black hetero marriages where wives are non-monogamous and reward their good lovers with Red Lobster, shopping trips, chopper rides, and the possibility of radio play. It’s the words ‘Stop Shooting Us’ spray-painted on a wall. “Formation” is a magical place where police cars sink under the weight of female blackness; where white riot squads surrender to black boys’ rhythmic complexity; and where black girls play ring games unbothered and uncontained. “Formation” is a newspaper called The Truth with a picture of Martin Luther King Jr. and the words “Why was a revolutionary recast as an acceptable Negro leader?” “Formation” is a warning to mainstream media not to attempt to strip Beyoncé of the politics born of her Creole Texas Bama blackness. But it’s also a warning to black folks to lay off the respectability politics that obsessively dissect and admonish Beyoncé for things as absurd as her daughter’s hairstyles (which, for the record, Beyoncé likes with “baby hair and afros.”)

The impact of “Formation” is derived precisely from this rich multivocality. Mae Gwendolyn Brooks argues that black women writers have long used multiple voices in their work because it allows them to “communicate in a diversity of discourses.” Not as a means to integrate into the white mainstream but instead to “remain on the borders of discourse, speaking from the vantage point of the insider/outsider.” In “Formation,” black women’s bodies are literally choreographed into lines and borders that permit them to physically be both inside and outside of a multitude of vantage points. And what that choreography reveals is the embodiment of a particular kind of 21st Century black feminist freedom in the United States of America; one that is ambitious, spiritual, decisive, sexual, capitalist, loving, and communal.

In terms of content and presentation, “Formation” is an excellent political pop song-video, but the breadth of its reach and impact is made possible because of Beyoncé’s marketing and business acumen. Without any warning, “Formation” came out the day after what would have been Trayvon Martin’s 21st birthday and the day before the Super Bowl that Beyoncé was scheduled to perform in. How could folks not talk about “Formation” regardless of whether or not they wanted to engage in its overt endorsement of the #BlackLivesMatter movement? How could folks not speculate about whether or not Beyoncé would perform it at the Super Bowl? With the unannounced release of “Formation” on Tidal on the eve of the United States’ premiere sporting event Beyoncé turned Super Bowl 50 and Coldplay’s halftime show into opening acts for the live premiere of her new song about female blackness, race in the United States and capitalism. Her performance was, of course, followed by a commercial advertising upcoming ticket sales for her next tour.

Beyoncé gave her first master class in 21st Century music industry marketing and business when she released her self-titled album in December 2013. It was then that she established that she no longer needed traditional marketing to release her music and have it be financially viable. Instead, she had a 30-second video uploaded to her Instagram account that announced to her 30 million followers that she had 14 new songs and 17 new videos available on iTunes. In three days her album was number one on iTunes in 104 countries.

In the months that followed postings to the same Instagram account that propelled her album’s success dwindled to a few sporadic posts, uploads on www.beyonce.com simultaneously increased. Most pop stars wouldn’t have the confidence to walk away from an audience of more than 30 million people. Beyoncé did. She must have decided that she no longer needed Instagram; and judging from the speed with which “Formation” is racking up views on YouTube—she was right. And now that TIDAL’s here Beyoncé no longer needs iTunes. Instead, she releases her music directly to the streaming service that she’s a part owner of and uploads her video on her website and on YouTube. Furthermore, the sole music industry credit at the end of “Formation” is Parkwood Entertainment—Beyoncé’s company—and this too is a departure from her self-titled album which featured Colombia Records in its credits.

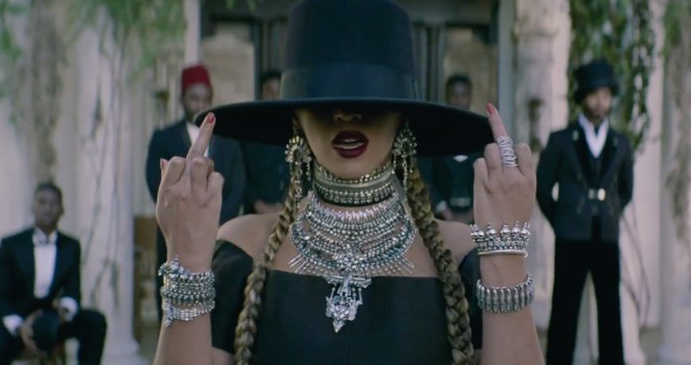

With the release of “Formation,” Beyoncé went from manipulating the pop culture music industry machine to usurping it. And that’s what freedom looks like when you’re a black female pop star in a capitalist country. As she sings in the last line of “Formation” with an unwavering gaze below the brim of a low slung hat “best revenge is your paper.”

There is an unflinching and relentless quality to Beyoncé’s performance of herself in “Formation.” She called women bitches and told us to bow down in 2013. This time she tells women to “get in formation,” prove they’ve “got some coordination,” and “Slay trick, or you get eliminated.” Black American feminists of the 1970s and 80s asserted that women needed to work together in order to survive heterosexism, racism, patriarchy and misogyny. What’s fascinating about the lyrics in “Formation” is that the black feminist capitalist coordination that Beyoncé endorses isn’t about survival, it’s about complete domination—the instruction is to ‘Slay’ and in fact, a woman’s ability to ‘slay’ is a basic requirement. And while this stance certainly has the potential to alienate an array of women, it also can serve as a clarion call to raise the bar in terms of black women’s expectations of what we can make of our lives—even in the face of the very real forms of violence and oppression that we face.

Angela Davis argued that when Billie Holiday put the song “Strange Fruit” (with its visceral description of the lynching of black people) in the middle of her live set in 1939 she changed the lens through which all of her previous songs should be seen and altered the lens through which any future songs should be heard. “Formation” is that song and video in Beyoncé’s career. There is a clarity, cohesiveness and command of aesthetics, lyrics, imagery, politics and pop culture in “Formation” that is profound and immeasurable. Her catalogue should no longer be listened to in the same way.

Last fall I taught a course at the University of Waterloo called Gender and Performance that focused on Beyoncé’s self-titled album. My course got copious amounts of press and two popular reactions emerged: there were those who were absolutely ecstatic that Beyoncé would be studied with intellectual rigour, and there were those who thought that her inclusion in university study signaled the demise of post-secondary education. My course analyzed the album’s videos through the themes of feminism, race and sexuality. The students learned to use black feminist and critical race theory to unpack the lyrics and the videos’ imagery. It was a deeply impactful and informative teaching experience for me as a professor because I’ve had never had students enter the classroom on the very first day as stakeholders in the subject matter—they’d grown up with Beyoncé, they knew her work, but had never deeply considered its larger historical, political and cultural contexts. We dissected those videos week after week questioning their content, impact and intentions. Had “Formation” been released prior to that class, the discussions would have been very different. This song-video significantly effects readings of Beyoncé’s previous work while simultaneously setting the bar for contemplations of her future work and she’s set that bar not higher, but on a different axis.

Beyond its resonance and importance to her own career, “Formation” is perhaps most impactfully a blueprint for other mainstream artists on how to unequivocally delve into the politics that matter to them while simultaneously holding mainstream attention. The Super Bowl halftime performance was a visceral reminder of what black music was and could again be in the United States. In the year that marks the 50th anniversary of the formation of the Black Panther Party, Beyoncé’s 28 black female dancers dominated the stage in signature berets, heeled combat boots, afros and black leather. It was an ode to the black civil rights era on the altar that is the Super Bowl stage in the United States. Just as Billie Holiday brought social awareness back with “Strange Fruit,” “Formation” has the potential to usher calls for black freedom from anti-black racism, state-sanctioned violence, and institutionalized poverty back to the forefront of black popular music. We would all be well served by that change.

Dr. Naila Keleta-Mae is a professor of Theatre and Performance at the University of Waterloo where she researches race, gender and performance. Follow her on Twitter.