This feature is part of ‘The Noisey Guide to Music and Mental Health’ (in association with Help Musicians UK).You can read more from this series right here, and follow ‘Mental Health Awareness Week’ on Twitter here.

– – –

Videos by VICE

Chris Hardman was born in 1990 in the traditional seaside town of Lowestoft, geographically the most eastern point of the United Kingdom. At the age of 15, he was an avid guitarist/songwriter and the shortest boy in his year at school, which earned him the nickname Lil’ Chris—the moniker most of us would come to know him by. After being spotted in auditions, he became a child star via Channel Four’s Rock School, and over the next two years, he supported Judas Priest and Rob Zombie, toured the world, scored a top ten hit, hosted his own television show (and starred in countless others), and released two albums.

But as fame faltered and years passed, he began to struggle repeatedly with bouts of depression and anxiety. In November 2014, he posted candidly on Twitter. “Going through your teens in the public eye really isn’t recommended by me,” he wrote. “Especially when you’re untrained and relatively uneducated.” Four months later, he was found by a friend in the rented house they shared, having taken his own life. Chris was 24 years old.

His death became a national news story, probably because something about it seemed all too tragically familiar. On the one hand, it was the story of yet another young man who felt the only option left was suicide: the biggest killer of British men under 50. On the other hand, it was the story of a child who found huge fame at an unfathomably early age, and seemed to spend the rest of their teens and twenties trying to cope with the polarising aftermath.

When I first saw the story, I saw similarities between the two of us: we were roughly the same age, had grown up in towns of similar sizes, and both dealt with mental illness in our teens and early twenties. I spent several years working in the music industry, witnessing first hand the distress it could inflict on its own kind from the bottom up to the top. Chris’s death brought to the surface that darker side of fame—particularly in youth—and the lack of support available for those in the industry affected by mental illness. Where is the support for those who are chewed up and spat out by the music business? When will we learn about the consequences of fame at a young age? And underlying all that: what can we do to prevent this from happening again?

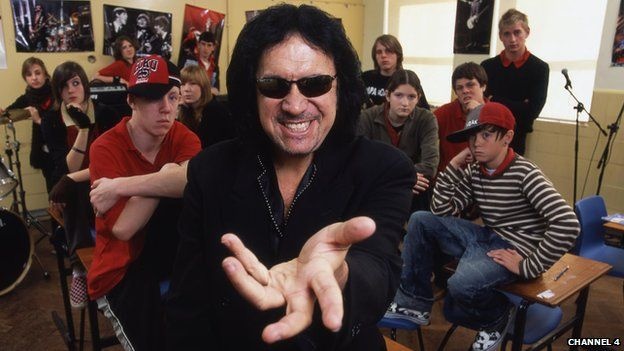

Photo via Channel Four

A decade ago, Channel 4 introduced its audience to Rock School, a reality TV show which saw Gene Simmons attempt to form a rock band made up of school children in a relatively short time span. In its second and final series, the programme brought the KISS frontman and a film crew to Kirkley Community High School in the county of Suffolk, where we met, among other students, a then 15-year-old Lil’ Chris.

“He auditioned, and I think being that cheeky personality that he was, he really caught the eye of the producers,” says his older sister, Hannah. “We actually had a holiday booked to Florida. We’d been saving up, and the filming was going to take place during the holiday. My parents were unsure whether he could even do it.” Their mother worked in the dairy department at the local Co-Op and their father in an abattoir. In Hannah’s words: “They’re just like country folk and they didn’t realise the scale of the opportunity, or how passionate Chris was about doing the show.” In the end, they agreed.

Chris went on to be selected as the lead singer of the band, Hoax UK, and the final episode of Rock School saw the group opening for Judas Priest, Anthrax, and Rob Zombie at a show in Long Beach, California. Following his success on the programme, he was signed to RCA, through which he released his debut single “Checkin’ It Out” in September 2006, reaching number three in the UK charts. It was a surreal time for his family, but even more so for Chris who was thrust into international fame. He’d celebrated his sixteenth birthday just a month earlier.

I ask Hannah how he seemed to deal with his newfound notoriety at the time. “I think there’s two sides to this question. When it was happening, I think that he didn’t need to deal with it; it was kind of like the adrenaline that kept him going. But looking back, I think it was a lot to deal with. Emotionally, physically—I don’t think that you can ever be prepared for it. There’s no support there to tell you how your life is going to change forever; how people are going to say good things about you and bad things about you; how you’re going be in the limelight, and you’re going to be judged. To have to deal with that must be very difficult.”

Hannah insists that while Chris’s personality never changed with fame (“Through everything ever, he was always the same, charismatic, practical joker”), the way he looked at the world and dealt with everyday life did. She recalls reading an article about Robbie Williams in which he talks about how difficult it is to comprehend standing in front of tens of thousands of people, singing his heart out with everyone cheering him on, to then go an hour later and be sat in front of the TV at home.

“I think about that and I think, hang on a minute, that’s such a big change in your day to go from something so draining and exciting to then all of a sudden be sitting at home by yourself. I think all those highs must have come with lows.”

“Former child star” is practically synonymous with some sort of psychological roller coaster. Countless actors and musicians who grew up in the glare of the media have gone on to battle severe mental illness, substance abuse problems, instability and doomed personal relationships. Having your every move documented and commented on is enough to ruin even the most well-grounded of adults, but for children or teenagers it may as well be a one-way street to severe mental distress. At the very least, encountering fame in your early years prevents you entering adulthood with any sense of normality.

“I struggle to watch particular programmes where young child stars are being thrusted into [fame]. Fame isn’t what it used to be when the Beatles were around. Now it’s one big bang: you have it and then it’s gone. Fame is fickle, and I think that we’re pushing all of these children—and they are children—into it. Whether they be 15, 16, 18, or 20, we’re pushing them into this music world that is not a stable environment. It’s not a ‘go to work, do your job, come home’ job. It’s an explosion of ‘do this, do that’—one minute you’re here, one minute you’re there, suddenly you’re this, and then you’re that.”

In April 2014, Justin Bieber found himself at the centre of controversy after posing in front of the Yasukuni war shrine in Tokyo, regarded by China and South Korea as an offensive symbol of Japanese militarism. It may have been a regrettable move on Bieber’s part, but for an average 20-year-old it’s unlikely any eyebrows would have been raised. Chris tweeted at the time: “So @justinbieber takes a picture with a shrine he knows nothing about and isn’t necessarily supposed to. Low and behold. Controversy.” Though Lil’ Chris never reached the same heights as Bieber, he knew what it was like to be a young person unable to live a normal life.

“I think we have this really bizarre way with famous people,” says Hannah, who is now a primary school teacher. “It’s like they’re not people. I get really cross. I can’t read magazines and things that slate celebrities for things that are no one’s business. I have a lot of debates at work, because I work with a majority women staff, and they’re all into their gossip. Quite a lot of the time they say: ‘Well [that celebrity] chose that to be their job, they chose that to be their life.’ I’m like ‘Yeah, but did they?’ You’ve chosen [being a teacher as] your job but when a parent comes in and shouts at you, you feel like that’s not part of your job. So why can’t these people who are famous have a life and be able to have flaws?”

The “they chose this life” argument is a fascinating one, particularly in the context of Lil’ Chris, who was just 15 when Channel 4 and RCA rocketed him to fame. Having to live your life by the choices you made in your teens, for your career to be defined while you’re still in high school, is a nightmarish thought to even entertain. “The things I used to say and do,” Hannah laughs. “I literally sometimes sit and shrivel up about it. At that age, you’re not mentally developed enough to make the decisions that are going to influence you and impact your future.”

Fame has come with its multitude of problems for as long as the concept of “celebrity” has existed, but with the advent of social media, and the online and print press and fans both mining an artist’s tweets and posts for either stories or connections, there is less and less opportunity to “switch the fame off,” so to speak. “If you put on top of that the music industry, which is a cruel place,” explains Hannah, “then you’ve got the fast pace of social media, the fast pace of the music industry (one hit wonders etc.)—dealing with all of that and then dealing with being a person? I wouldn’t be able to cope.”

Although her family believes they did everything in their power to help Chris, his fame meant that it was difficult to avoid interference from outsiders who simply didn’t grasp the gravity of his situation. All it takes, Hannah says, is one person to say, publish or do something—whether or not it has any malicious intent—and it can set someone who suffers from mental illness back to square one. When you’re famous, the power of having the most supportive family and friends in the world is reduced when you’re open to scrutiny at all times and have little choice about whether you are publicly discussed in a positive or negative light.

But perhaps the main cruelty of experiencing stardom at a young age is how unprepared you are for when a once hugely promising career falters. Lil’ Chris never matched the success of his first single, and after a few albums he spent the next few years working odd jobs both in and out of the world of performing, even spending a brief time as a door-to-door salesman. At the age of 20, he was cast in the production of Loserville: The Musical, which initially ran in Leeds before transferring to the West End. But for much of the show’s London run his role was played by an understudy, for reasons that, in retrospect, are now a lot more clear. It was around this time, his family says, that his mental health really started to decline. Hannah had spent a year and a half living in Australia and during that period she could tell from conversations with Chris and their parents that things were getting worse. When Hannah came back to the UK she moved in with Chris in London, a period she describes as “heartbreaking.”

“It was like he was being taken over by these mental health issues, by his anxiety, and by his depression, and that’s a really hard thing to see. There’s nothing you can do about it. You try and you try, everyone tries and then you worry that you’re trying too hard and you’re saying the wrong thing, and then you don’t say anything, and then you’re worried about that. How many times I’ve sat and gone through things I said and thought: ‘Oh god, I should have said that or I should have said this.’ It’s awful; it’s so hard.”

Chris never hid his health problems from his family or, indeed, his wider fanbase. On several occasions he tweeted about it, writing in October 2014: “Depression really sucks. Learning how to notice it can save lives and your own feelings at times. Take time to understand it, for everybody.” He sought help from a number of different mental health services and workers, but ultimately this provided only brief moments of respite from his illness.

“He’d go and speak to someone and then he’d come out and it would be like the doors had opened and he’d had this epiphany. And he’d be great and it would be like, ‘Here he is again, that’s my brother!’ But within a few days he’d be back to where he was to begin with. I guess that is severe mental illness; there is no taking a tablet and it’s better. It’s a constant battle and struggle, and I think that’s where we as a society fail people with mental illness. Because we can’t physically see it, it’s like as a society we can’t cope. We have a stiff upper lip about it. And that’s not helping at all.”

Chris died on the 23rd of March 2015. In the subsequent inquest, Suffolk coroner Peter Dean noted: “Clearly he was a very talented young man who found fame at an early age. Sadly that fame also brought with it difficulties and problems, but he had shown a desire to relaunch that career once more.”

There were undoubtedly many factors behind his decision to end his life. “You can’t define whether it was the music or the fame or everything he went through,” explains Hannah, “or whether that was always going to be what happened, because he was so young.” It does, however, seem inevitable that his particular circumstances contributed to or otherwise exacerbated existing mental health problems. And what’s absolutely certain is that more has to be done within the music industry to support young stars.

Hannah thinks there needs to be some regulation of sorts. “Not an age restriction, but sort of a courtesy to say: ‘Hang on a minute, these young people we’re working with, we’re affecting them for the rest of their lives.’ Or there needs to be a support blanket of: ‘We’re going to work with these young people but we’re also going to make sure they’re still gaining skills that are necessary for life, that we’re supporting them mentally, and that we’re talking about things with them.’”

It’s not unfair to say that we as a society have struggled with the stigma associated with mental health problems, and one in five of us still believe that the main cause is simply “a lack of self-discipline and willpower.” But in the music industry it seems to be even more difficult for those suffering from mental distress, as the need to maintain a pristine and flawless public image is deemed tantamount to succes, and often preached as the way things should be done. “That is a big problem,” says Hannah. “We need to take down those barriers that say mental illness is something that can’t be talked about or something that people should almost be ashamed of.”

In the past few years we’ve heard powerful accounts from those within the music industry about how musicians suffering from mental illness feel unsupported, but there’s a whole other level of responsibility at play when the star in question is a child. There are systems in place to supposedly protect child stars, but unless parents are properly informed about what they’re signing their children up to they’re of little use. Just because something is legally sound doesn’t mean it’s ethically so.

“I think the music industry fantasises the idea of being a musician. My parents are normal people. They have a house and a dog and three children. When it all first happened, the fact Chris was so passionate about it felt like a version of: ‘Mum, please buy me that big Optimus Prime toy on the shelf’,” explains Hannah. “I think that was played on by the label: ‘Yeah: we’ll look after him. Yeah: we’ll take care of him.’”

“In the record label’s defence, maybe the mental health of a child is not something they automatically think of—no broken arms, no broken legs—maybe that’s not on their little checklist. But it should be.”

That is changing to some extent. The British charity Help Musicians UK have now began consultation with the music industry, and have conducted ‘Health and Wellbeing’ surveys of it with a view to highlighting the breadth of mental health problems and amplifying the conversation around it. At The Great Escape festival in Brighton this year, they will be hosting a series of conferences on the topic, and unveiling new academic research commissioned into the mental health of music professionals.

But for all the policy changes and regulations that could improve how the music industry addresses mental illness, Hannah thinks the main thing required is no different to what is necessary in wider society. People need to be better educated about mental illness and a far bigger conversation than is happening currently needs to take place. Much of the stigma surrounding suicide especially can be traced back to our reluctance to discuss these issues openly, and unfortunately that’s led to a self-perpetuating cycle of destruction.

“I get really angry and upset when people look down their nose at suicide because I think you just have no idea what it must be like for people. It wasn’t for attention. It wasn’t for any other reason than that was the only way he could cope. I think that’s where this education needs to come in.”

Chris may not be the most instantly relatable case study for our nation’s men, because of the added social factor of his child stardom, but the fact remains that when a man of his age dies, there’s a one in four chance he took his own life. And if we’re to stand a chance at beating the statistics that’ve fallen on Britain’s young men, we need to take it upon ourselves to raise the barriers we’ve put in place, by talking about mental health and raising awareness. That’s something that CALM, the Campaign Against Living Miserably, is dedicated to changing.

For the Hardman family, though, the pain is still fresh. Their parents have thrown themselves into whatever they can to stay busy; to lose a brother is hard enough, Hannah says, but to lose a son? “I can’t imagine what’s it like.” Just under a year before he died, Chris wrote on Twitter: “I hope to one day create a way out of depression that doesn’t mean taking your own life. The Cure.” Hannah tells me she thinks about that tweet every day, and though it’s hard to find a silver lining in a cloud this grey, it strikes me that in her willingness to talk about such a traumatic event (not only to Noisey, but also on daytime television), she is giving power not only to herself but to the memory of her brother; to ensure he is remembered not by how he died, but by how he lived. It can be incredibly difficult to talk about suicide, but if there’s one thing we must not be, it’s silent.

“I think that for me the more I talk about it and the more I do things like this, the more I feel like almost in a silly way that everything happens for a reason, and maybe the reason that Chris had to leave us was for his story to get told. He’s no longer with us but his legacy can be carried on for pushing it out there, educating people and talking about it.”

You can follow Jack on Twitter

This feature is part of ‘The Noisey Guide to Music and Mental Health’. You can read more from this series right here. If you are concerned about the mental health of you or someone you know, talk to Mind on 0300 123 3393 or at their website, here. And if you would like to know more about the work of Help Musicians UK, you can visit them here.