Dave Navarro at Fun Fun Fun Fest 2015, photo by Gary Miller/Getty Images

Though best known as the long-time guitarist for seminal 90s psych-alternative group Jane’s Addiction, Dave Navarro has embraced nearly every aspect of American celebrity. Aside from a music career that has included working with everyone from Michael Jackson to Christina Aguilera to The Red Hot Chili Peppers, Navarro’s spotlight has included stints as a television host (Ink Master), actor (Sons of Anarchy), and, of course, making his directorial debut with the 2007 porn flick Broken.

Videos by VICE

There was the brief marriage to Carmen Electra, which also included a television series documenting the couple’s wedding and four-year marriage—an impressive duration given the shelf life of Hollywood nuptials (see: literally almost celebrity who’s been dumb enough to get married). Navarro also found himself on the Los Angeles Times best-seller list with his autobiography Don’t Try This at Home, a book documenting what a year in his life looks like. It’s surprisingly not anywhere near as completely fucked as one might assume—he’s no Nikki Sixx, whose biography reads like a laundry list of ways to put yourself in a coma.

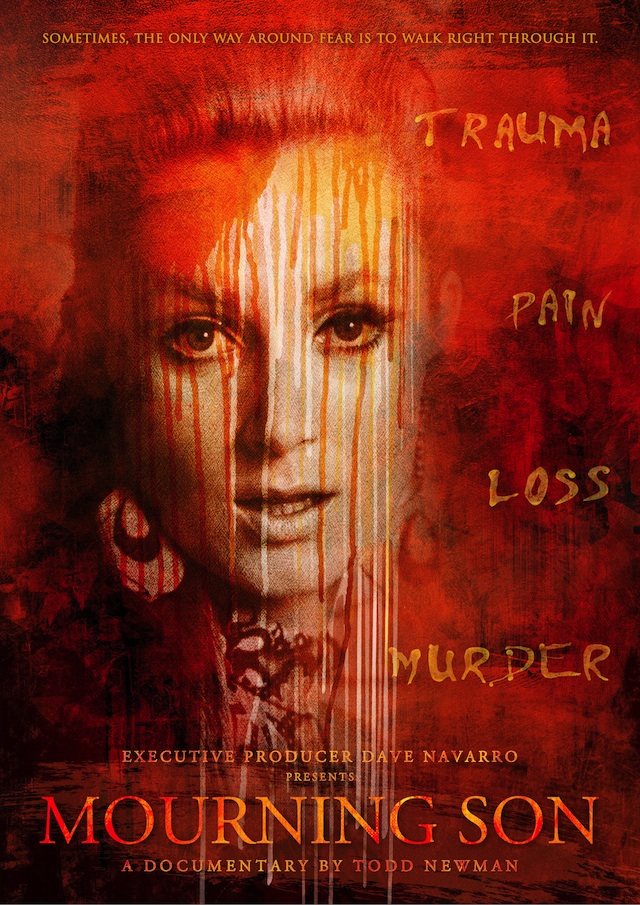

While Navarro’s notoriety and presence in the public spectrum is and has been potent for a considerable amount of time, his identity as a person with deep and potentially crippling life experiences can, like with many celebrities, get lost in the fray of reactionary sensationalism. At 15, Navarro was plunged into an unimaginable world of trauma and grief, which led to the resulting struggle of addiction. In 1983 Navarro’s mother Constance was murdered as a direct result of domestic abuse. The murder is the subject of a new documentary called Mourning Son, which Navarro made with partner Todd Newman. For Navarro, the tragedy merited a documentary that, unlike so many crime documentaries, would not spotlight the criminal but instead would focus on the aftershocks of the criminal’s actions.

A truly gut-wrenching viewing experience, Mourning Son is not only a documentation of Navarro’s loss—it’s even moreso an unflinching look at the horrors of domestic violence. It takes little time, but the cocky swagger of Navarro’s public persona is stripped away, revealing that 15-year-old boy whose unthinkable nightmare became an unforgiving and life-altering reality. In our recent conversation, I felt it would be appropriate to open up the discussion by talking to Dave about the recent news of Scott Weiland’s death, and how widespread publicity of grief doesn’t make it any less difficult to face or any less personal.

Noisey: With the recent news of Scott Weiland, it’s something that bears a lot of relevance to what you discuss in Mourning Son just in terms of the fragility of life and the experience of losing someone close to you. I’m assuming you and Scott were fairly close. What was your initial reaction to hearing about his death?

Dave Navarro: To be perfectly honest with you, I read about the passing of Scott on the KNAC website, and I was stunned by it. Obviously I was sad and shaken by it, so I tweeted how sad I was to hear that. What ended up happening is I guess somehow I was one of the first people to tweet about it, which ended up getting picked up by all kinds of news sources because of retweets and things. For some reason my name has been brought up quite a bit in the story of his passing, which is unfortunate. It’s really about him, and it’s about his family, and his kids, and his legacy, so I actually ended up taking the tweet down, because I felt that it’s not my place to be mentioned in that story. I think just to be respectful and fair, I was a little worried that that ended up happening as a byproduct of social media. I had read about it, and I just thought it was out, and I was just thinking: Oh my God. That’s terrible. My reaction was I was deeply saddened by it.

Scott was a friend, and he was somebody I played music with and had known for decades. He and I used to do drugs together, and we were clean together. It was really… I don’t know how to put it. It was one of those shocks that is hard to describe, because I think for any of us in this community, the music community, and certainly any of us who has had a history with drugs—and I consider myself one of those people—we all are pretty aware that what we’re doing could kill us, myself included. When one of us passes, on certain levels it’s not a shock, but then on a very primal, human level, it’s one of the most shocking things that you can learn, because the type of shock you’re prepared for is not the kind of shock that rips through your heart. You prepare for an intellectual shock, and you’re given an emotional shock, and it’s hard to reconcile the two.

Talking about Mourning Son, was there a specific thing that compelled you to make the documentary? Was this the perfect time to tell this story?

There’s really no real answer for that. I think the truth of the matter is that my partner Todd Newman and I were talking about making a full-length film, and we decided to tell this story because I know it inside and out. We wanted to learn how to make a film, to be honest, so we just got in a car with video cameras and got going without really knowing what we were doing. We just sort of learned as we went. We’d both made short films, and we’d both worked in the different visual arts, but this was the first time we’d attempted to make a feature-length film. I think the subject matter, believe it or not, kind of came second in terms of us venturing into making a long film. Then I found the subject matter, and in the process of making the film, I came to realize how much this story could benefit others.

I don’t think we really knew what we were making – if we were making a cautionary tale, if we were making something biographical, if we were making artistic, because we really wanted to keep it heavily artsy without waving that flag too much, but we wanted that artistic element, which you don’t really see in documentaries all that much. We made it over the course of several years, so the whole framework of this thing evolved over time.

When you talk about the benefit of the film on others, that’s not exactly a common aspect of crime documentaries, just generally speaking. That said, the one thing that seems to really underscore the story in this documentary is the subject of domestic violence. Was that something you wanted in terms of offering a different perspective on a popular type of documentary?

Yeah. I mean, I’ll admit that I’m a fan of all the investigative, true crime shows that are available. We have 24-hour networks devoted to true crime stories, and those shows are wildly successful: 48 Hours, Dateline, Investigation Discovery, even The Jinx and the Robert Durst story. It’s fascinating, but most of those stories will focus on the perpetrator and the psychology of the perpetrator, and we didn’t want to tell that story. I don’t want to know about this perpetrator, and I don’t want to tell his story. I wanted to tell the story of the family afterwards and having to get through something like this, and the profound effect it has on so many people’s lives. When you think of a murder, most people—and I may be misspeaking, but most people—don’t think of it as a domestic violence situation; they think of it as a murder. But it is that. Most of the time it’s a result of domestic violence to the Nth degree, so I felt that if we could tell some kind of cautionary tale in the process of this whole thing, that alone would make the story worth telling.

Is the issue of domestic violence and our culture’s discussion about it something you see as being more conducive to change now as opposed to 20 or 30 years ago when this happened?

I’ve been working with a couple of different organizations helping to spread the message and spreading the word that there are outlets and facilities in place that are safe havens for anybody going through something like that. It’s not just women. I hate to make it a specific thing, and nine times out of ten it is involving women, but there are abusive gay relationships, there are women who are abusive to their husbands, or whatever it might be. The idea is that anyone who’s in danger, I’m trying to spread a little bit of hope in terms of hope and where people can go to find support. In 1983, there wasn’t the internet, and there wasn’t the kind of messaging and dialogue, and now there is, so I certainly see it getting better. I don’t know if we could identify what was going on or have a name for it then.

One thing that Mourning Son also speaks to is your own struggles with addiction. It’s a strange kind of rock ‘n’ roll celebrity dynamic that these things: Addiction, mental issues, and untimely deaths are treated almost like a trope by the press and fans, despite the fact that these people, like Scott and so many of the others are struggling through the human experience. Is that something you’ve seen as well?

I mean, it’s a sticky subject when you talk about celebrity. I get that anytime you talk about the idea of celebrity it’s something that has that aspect of fiction, but on the other hand, they’re still strangers to me. I’m still a stranger to everybody else except my immediate family and my friends. There may be some kind of creative connection. I do like that you’re talking about the human experience, but my reaction to something like Scott is a lot different than that of someone who’s a music fan, because I shared that human experience with him. I shared the human experience with my mom. I shared the human experience with a lot of people going through some super hard times, but then again I haven’t shared it with maybe another person in the news. I’ve talked about those things before, but maybe my reaction is a little less powerful because of that.

I’ve found that in my own experience, the people I love the most and the people that I cherish, or that I care about, or who care about me and have been there for me, that I don’t really turn to the fanbase for emotional support. [Laughs] I think it’s a wise thing not to do that. I’m not looking for anything from anybody, because obviously I found my path to some kind of healing. I think that ultimately what I wanted to do was say: Look, everybody goes through something. Maybe you didn’t go through this, but maybe you had a dog die, or you lost something you loved, you broke up with a partner that you really cared about, and you had your heart broken, or whatever the case is with each person, it doesn’t matter so long as they understand that there is a path around it. There’s a refuge from it.

For me, being a creative person and putting all of my art into those outlets is what works for me. It doesn’t work for everybody, but something will work. It will, and I think that the ultimate message of this film, to simplify it, is that there are really damaging ways through trauma, and there are really healing ways through trauma. I’m sure you and I both know people who have not found those healing ways through, and even those who didn’t make it. I’m very fortunate that my attempts at going through the negative ways of going through trauma didn’t kill me. I’m so grateful for that. The drugs nearly took me and could have easily made me another headline, so if I’ve been spared, then I have an obligation to make a difference in somebody else’s life.

Follow Jonathan Dick on Twitter.