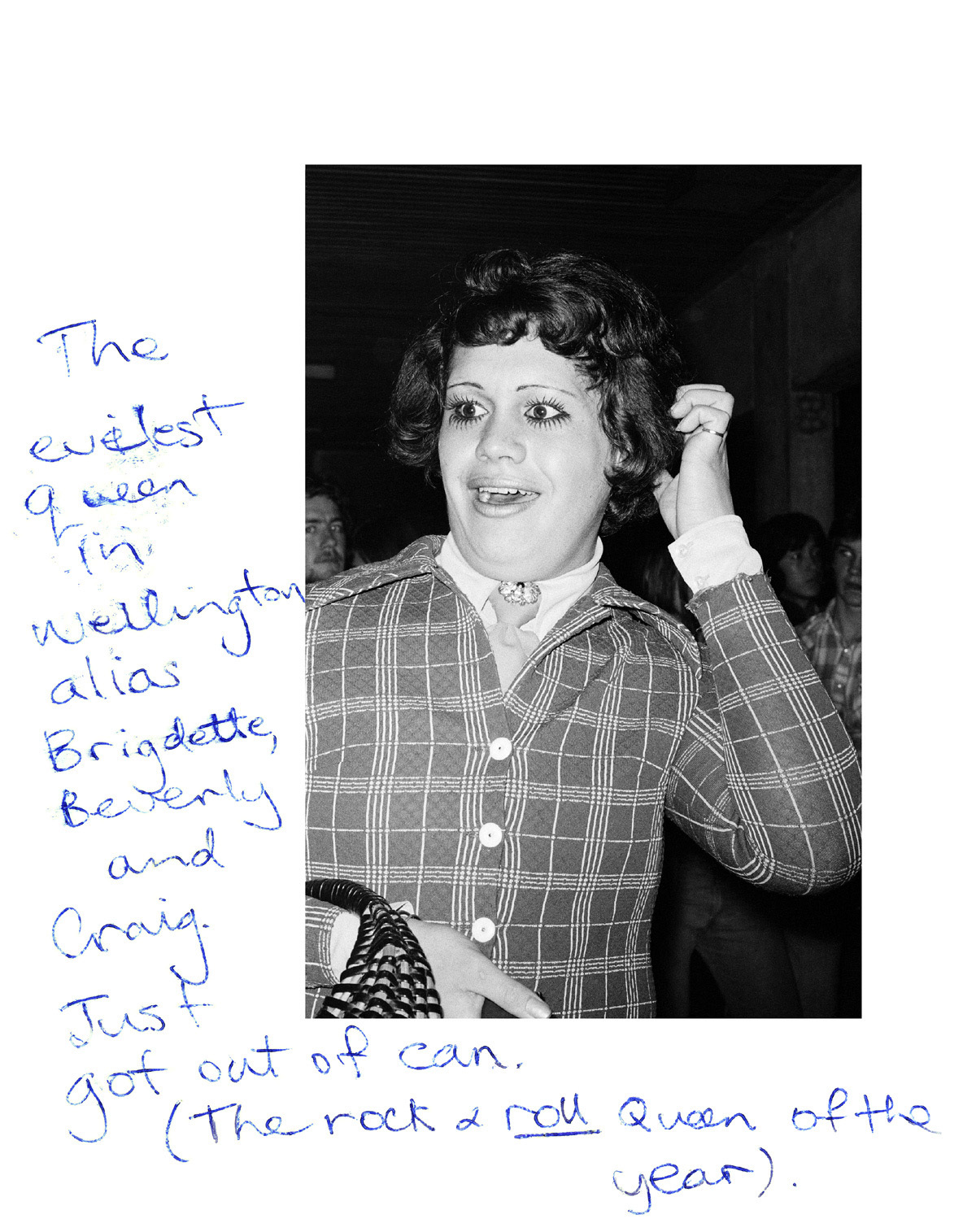

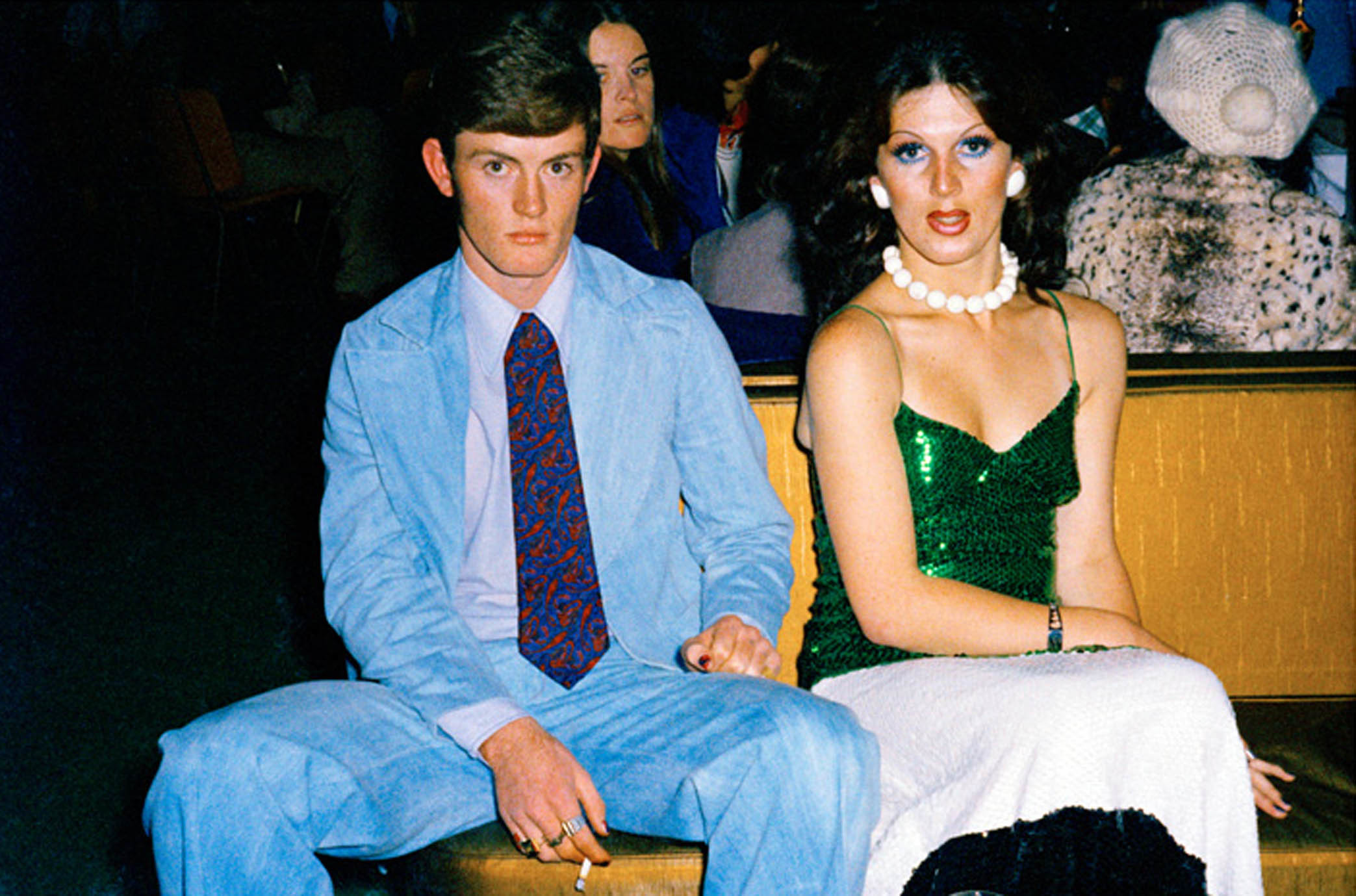

All images by Fiona Clark. Diana and Sheila at Mojos nightclub 1975

In the 70s and 80s, Fiona Clark was one of the first photographers to shoot New Zealand’s LGBT scene. She captured her friends at parties and in their homes, and her images were warm portraits of the city’s cultural fringe. In many ways she’s a contemporary of Carol Jerrems, Rennie Ellis, and Nan Goldin. But censorship and public outcry kept her from exhibiting much of her work. As a result, she never reached their levels of fame.

Rather than moving to New York or London to become an alternative art star she returned home to Waitara. There she began documenting another community with the same dedication she gave her city friends.

Videos by VICE

Thirty years later, a new wave of fans have begun to discover and appreciate her work, and her photos are enjoying another life. Now she considers herself an artist activist, and focuses on environmental and social issues around her home. We called her up to talk about New Zealand in the 70s and 80s, and the art of shifting focus.

Bev at Dance Party Auckland, 1974

VICE: Hey Fiona, I feel like a lot of young New Zealanders see their culture as being pretty progressive. But what did the social climate feel like as a young person in the 70s and 80s?

Fiona Clark: I don’t think it was as progressive as people think. I couldn’t show the work I did publicly as a collection until 2004. It was as progressive as the homophobia that existed. Within institutions there was homophobia, and that restricted the way people worked. It was a reflection really, and some of it was really hard for me. Galleries told me I was unsellable. Although 42 years later, there is a new interest.

Your show Active Eye was infamous and had images removed in 1974. What was it specifically that upset everyone so much?

That it was letting people be visible and saying we’re here, we’re not going away, we occupy space, accept it. They weren’t confrontational—for me they weren’t. They were portraits of people I had an affinity with, and who I wanted to record.

People said, “can’t you just photograph common people?” But these were the common people in my life. And still that doesn’t exist that much.

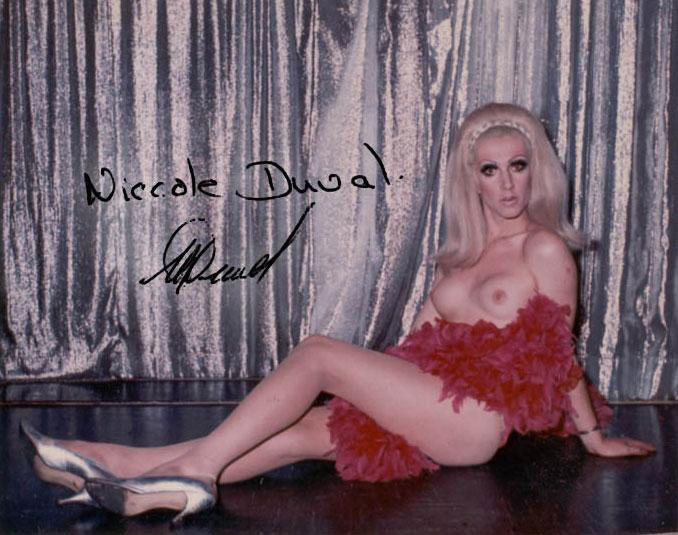

From Fiona’s 1970s ‘Go Girl’ Series

Why did you hand print all your images?

Quite often in those days, if you sent something off to a Kodak lab, they censored the work. So I was running a color darkroom as well.

With attitudes that ingrained, how did you manage to develop any reputation? As you said, a lot of your work is only now being fully exhibited.

I’m like the people I photographed and hung out with, we’re survivors. I just survived it. I admired the tenacity and survival capabilities of those people. They are more hardened than I am. People have lived far tougher lives than me. And I have always had a belief in the work. The work is about survival.

K.G. Club, 1974. Opened in 1971, The K.G. Club was Auckland’s first lesbian social club.

Why didn’t you just leave New Zealand? London, New York, even Australia were beginning to celebrate content like this.

I considered it. I thought of going somewhere and studying—to London to the Royal College of Art. That was the progression from Auckland as an artist. But after the Active Art show I had a prosecution, and I felt pretty beaten up. Galleries were saying, “no you’re not showing here.” I sort of snuck off to the country. And I still live here, in the same place a snuck off to 40 years ago.

Then I had a bad accident so I couldn’t go anywhere for a couple of years. But I didn’t get any offers of people saying you should show this work somewhere else.

Diana and Peri at miss NZ Drag Ball, 1975

Do you have regrets?

I don’t regret not doing it, because I fitted into here, into the community I’d come back to. Unfortunately, not comfortably for a lot of people. But the involvement I have with the community now is on the same level. I’m taking photos of things people aren’t recording, and of parts of our community that are still invisible.

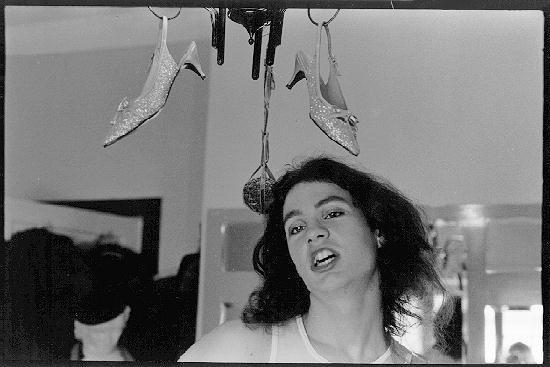

Carmen in her Sydney home, 2006

Has the controversial label ultimately been a prize or a burden?

It’s something I’ve accepted. I call myself an activist artist now. I’m not just a photographer, I believe I am an activist. But people don’t sit comfortably with that. They certainly don’t like the work I’ve produced so they’ll dismiss it. Sometimes it’s hard, but I know to just dig my toes in. I’ve spent this year cataloging my work. I’m more determined now that it lasts even longer.

Miss K, a.k.a. Ella, at home in Auckland, 2001

Have you had any more brushes with controversy?

Yes, I have actually. I live near oil and gas fields, and the local community has gone in front of the local council and said we’re upset by this, we want these things changed. I’ve produced images and said, these are toxic waste sites and they’re harming the people who live nearby. The previous mayor challenged me and said, “You can’t say that.” I said, “I’m not saying it, the image is there. There is a warning sign, but here’s a house, all in the image.”

Todd Energy flaring after fracking at Mangahewa D well site June 18, 2014

I do get challenged about presenting images that are upfront. I’ve had a trespass notice served to me from an oil company. I’ve photographed the run off and the way the oil industry effects local people. The politics of it are interesting, but I do get called to the mayor’s offices. But I just think, this is calm when you compare it to being threatened in a club in Auckland.

Follow Wendy on Twitter.