The stadium erupts with applause and confetti, and all of a sudden, Bradley Ray Moore is famous. In fact, as millions watch agog from bars and living rooms across South Korea, he’s probably the most famous white guy in the country—if not the whole history of Korean music. Moore didn’t intend to be here, and it’s the last thing on his mind; right now he just wants his fiancé back, and his freedom. He’s been shuttered from the outside world for two months, and if he screws this up, it’ll be a long time before his next chance to escape.

Moore spots Danielle Bacon in the undulating crowd of 10,000 and, heart racing, motions for her to rush the stage. A trained athlete, she vaults past the cameramen and barriers before being seized by a hulking bodyguard. But he soon realizes this is the Dani he’s heard so much about from Moore, with whom he’s developed a rapport as his personal protection. He lets her pass.

Videos by VICE

Moore grabs Bacon’s hand and clasps it tight, remembering a recent warning: “People might try to break that grip—physically.” Some dozen bodies quickly engulf them, and after an anxious moment, Moore sighs in relief; it’s the other contestants from Superstar K, the most renowned of Korea’s many talent search reality shows. The musicians—including Moore’s bandmates in the power pop trio Busker Busker—have swarmed Bacon and Moore to prevent anyone else from doing so.

The couple is safe for at least the next few hours, but Moore has gotten himself into one fascinating mess. Thin to begin with, he stands 25 pounds lighter from eight weeks on Superstar K’s schedule and diet; top Seoul stylists have remade him in the image of high-end designers and hair products; his cheeks still carry the toxins of a couple Botox shots fast regretted. Moore has been through the wringer of the K-Pop fame machine, and has some sense that if he doesn’t do something drastic, he and his bandmates will be further mangled. For now, this American drummer’s only goal is to avoid the luxury bus Superstar K wants them to board by night’s end. He doesn’t know where it’s going, but he’s had enough.

Moore knew almost nothing about Korea, let alone its music, when he decided to move there in 2008. He and Bacon, in their last semester at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, simply decided to try something new.

“We wanted to get out of the country, just do any job that would pay us,” Moore remembers. Bacon saw on their career network that they could each make $2000 a month teaching English to kindergarteners in Korea, without any previous exposure to the language or culture. “One day I went to class, she applied for the job, and within 24 hours got notice back saying she’d gotten it. They didn’t do an interview, or anything. So she replied, ‘My boyfriend wants a job, too,’ and they said yeah, bring him along—just make sure you graduate.”

The couple were assigned that fall to Cheonan, a city of 600,000 located an hour south of Seoul. After just one year of teaching kindergarteners there, Moore and Bacon were able to land intro-level positions at Sangmyung University, a local campus of some 20,000 students.

“In one year, we went from being crappy kindergarten teachers to tenure-track professors,” Moore marvels. At the time, they still spoke only cab-and-menu Korean.

There, during a failing oral exam with Moore, art student Hyung-Tae Kim asked his professor to join his band Busker Busker. Their drummer had just left for his mandatory military service, and the handsome teen had heard Moore knew how to play. He was a bit rusty, and had never taken the drums too seriously, but that hardly mattered; drummers are an endangered species in Korea, and Kim had started playing bass just a couple of months ago anyway.

At Moore’s first practice, frontman Beom-Jun Jang received a call from Superstar K. Recently hailed “the king of cable” in Korea, the show was already fielding some two million auditions for their upcoming season. But virtually all of them were solo acts, and Superstar K wanted to feature some groups. Jang, a wholesomely boyish singer-songwriter and Sangmyung art major, had been rejected in the preliminary rounds for both of the show’s previous seasons—but they had heard he was now fronting a band. That a genuine American Idol equivalent not only knew Busker Busker existed, but also had to ask them to apply, demonstrates how thoroughly the K-Pop industry has eviscerated Korea’s rock scene: Moore and company were complete nobodies, even in Cheonan.

“They just needed diversity in their narrative, in their broadcasting—so they had us come in to make the show look successful,” Moore explains. “Even though they had called us.”

The band made it all the way to the televised proving ground known as “Superstar Week,” a collaborative showdown featuring some top 150 contestants. They were paired with Two Months, a Korean teen duo with whom they were to perform a cover of SHINee’s 2009 hit “Juliette.”

“When they linked us up with these kids, the narrative had already been set: Two Months were passing, Busker Busker was failing,” Moore says. “That was predetermined, we found out later…[the producers] just didn’t think we were marketable.”

But a few weeks after Busker Busker were sent home, something funny happened: their version of “Juliette” aired, and became an overnight sensation. Ironically, this was thanks to how thoroughly Superstar K had to doctor it in post-production.

“The recording was so bad that Two Months had to go back in and re-record their vocals, because no one would’ve believed they passed with that performance,” Moore explains. “And the miking on these TV shows is crap, so the whole thing had to be super-produced. They had to Auto-Tune my drums, they had to Auto-Tune everything. So when they put it on television, it sounded like this really nice, professional track.”

K-Pop’s outspoken online community was in such a furor over Busker Busker’s dismissal that Superstar K offered to grandfather them back into the show’s Top 11. But Jang and Kim would have to drop out of college, and Moore would have to abruptly quit his professorship.

“I asked the show, if I leave my job for this, can I make money doing music? And they said probably not,” Moore recalls. “Don’t do this if you think you’re going to make more money than you did as a teacher, they said. Do it for the chance of having a story to tell.”

As soon as the band returned to the umbrage of Superstar K, the Korean entertainment industry’s peculiar darkness set upon them. Nobody had warned Moore of the autocratic living strictures upheld at the rural manor the remaining contestants called home. His phone and wallet were confiscated upon arrival, and he would remain confined until whenever Busker Busker lost. Their confidence was so low that the three only packed clothes for a week, but their startling popularity among viewers kept Moore cloistered there for the full two months of the program.

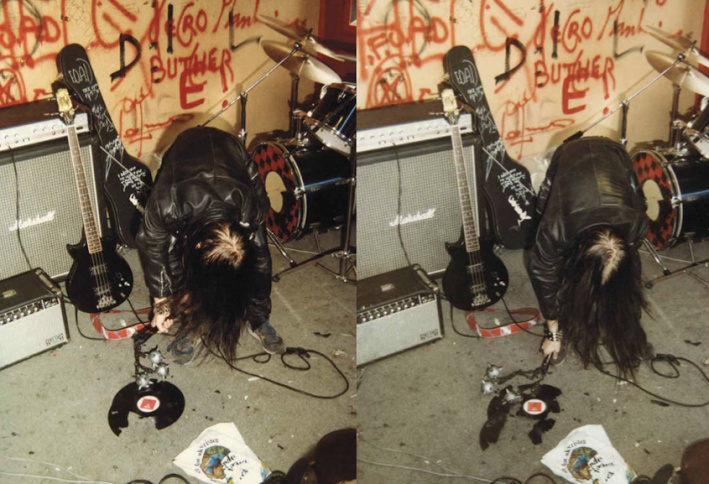

During that time, he was force fed a slimming diet of salad and tofu. “Involuntary makeup” was an everyday ritual, and the show’s producers frequently aimed snide barbs at the musicians’ physiques. Weirder still was Superstar K’s daily request for the contestants—mostly in their twenties or late teens—to take advantage of their gratis Botox regimens. Many obliged every few days, Moore remembers, and after some initial resistance he finally acquiesced. The program’s handlers transported Busker Busker into Seoul one afternoon with the only other band on the show, a heavy rock group called Haze.

“They’ve got their mohawks and studs, and we’re these three little dorks, all in this super downtown, Manhattan-style luxury clinic,” Moore says, shuddering. “And it looks so scary. There’s this freakish, Dr. Kevorkian chair in the middle of the room—just one chair—and sitting on top is a stuffed elephant. I sit down and they put it on my lap, and say, ‘You might wanna squeeze the elephant.’”

The needle was in Moore’s cheek before he could figure out how to form a question.

“Tears. Instant tears. You start squeezing the elephant just so you don’t scream and scratch yourself.” Moore could barely chew for several days, and the boys swore off cosmetic alchemy for good.

Despite its reputation as Korea’s most musician-friendly program, Superstar K allotted little time or resources for music. Groups were assigned their song of the week a night prior to its live broadcast, and during rehearsals Moore seldom had a kit. Instead, Busker Busker arranged inventive covers of their assignments (typically K-Pop smashes; once, “Livin’ La Vida Loca”) to the rhythm of metal chopsticks on an empty guitar case. They even had to fight just to play their instruments live.

“They thought I could just ‘not make contact’—like, get close, but not actually hit the drums,” Moore smiles. Superstar K capitulated, but took a few weeks to get it right: Busker’s first two televised performances barely survived a slew of technical difficulties, with Jang’s guitar amp cutting out mid-song.

In lieu of music, Superstar K filled its subjects’ time with what they called “VCR.” This daily, filmed servitude entailed the occasional skit or cutesy “mission,” but moreover, a marathon of brand name endorsements—for which Busker Busker and their peers received literal slave wage.

“We were popular because we were on TV, but we couldn’t legally make money,” Moore says, underscoring a strange norm in Korean entertainment law. “We were at ‘amateur status’ in the broadcasting contract. So, like, Coca-Cola comes in and we spend all day doing a Coca-Cola commercial, but they pay the [show’s] company—not the artist. We were on the show for eight weeks straight, and we did commercials for eight weeks straight. We took home no money from that.” On some days their schedule would go “over 24 hours”—Moore, Jang and Kim soon grew accustomed to napping between takes in bushes, on concrete.

Perhaps the most ridiculous aspect of the artists’ sacrificial pact with Superstar K was that this same rule applied to music sales. After Friday night’s live verdict, the remaining contestants would be trafficked covertly from countryside into Seoul—their bodyguards ensuring a 20-foot radius of separation from the public at all times. There they would each record a studio version of their song of the week, which was then released on Monday as a digital single via Korea’s numerous online retailers.

“Our sales were in the millions [USD]. One song, ‘Makgeollina,’ sold $1.4 million in a month and a half—and yet we saw nothing from that,” Moore says. “We were kind of a headache for the show: we had a foreigner in the group, my bandmates were young, we can’t read sheet music…but every time we recorded a song, it would hit #1. So they kinda kept us around.”

Superstar K in fact kept Busker Busker around until the very end, elevating them from Cheonan anonymity to nationwide fame in barely two months. Even then, Moore and his bandmates were so isolated that they couldn’t really comprehend the change; they were excited for other reasons.

“The last week was one of the happiest times in all our lives, because we knew that that Friday night, we could go home,” Moore recalls. Everyone on the show had known long in advance that Ulala Session, the other finalists, were all but scripted to win. “And then the next day, we were going to wake up in our beds. Our real beds.”

But even the long-awaited finish line came with a treacherous catch, which Busker Busker’s celebrity manager Seok-Hyeon Kim intimated while the cameras weren’t rolling.

“He was a contractor; he didn’t technically work for CJ E&M, the company [that owns Superstar K]. So he told us, ‘Contractually, guys, when it hits midnight on Friday, your deal dissolves and you’re free,’” Moore says. “‘But the company is gonna tell you otherwise.’”

“He was with us every day, so I was like, ‘But once midnight hits, man, you’ll be able to help us out—right?’ And he goes, ‘No no, I’m gonna disappear too, ‘cause that’s also when my contract ends. We’ll never see each other again.’”

They were terrified—but the manager did, however, impart some cryptic wisdom to Moore about Bacon, who would be in the crowd for the show’s finale.

“He said, ‘Okay, Ulala Session is going to be announced winners, they’ll say thank-yous, [you’re] gonna say thank-yous—and what you guys gotta do is get Dani up onstage,’” Moore recalls. “And he really emphasized, ‘Brad, don’t let go of her hand…Whatever you do, don’t let go, and don’t leave her side.’”

The manager also spoke of a luxury bus that would appear after midnight, which Superstar K would invite the band to board—going somewhere identified to Moore only as “the incubation house.” That was all he needed to know.

The show’s grand conclusion went exactly as planned, from Ulala Session’s victory to Moore’s triumphant reunion with Bacon. From there they all went to a lavish after-party at a private, CJ-owned club in Seoul, where they danced until dawn. By the time Superstar K’s ominous bus appeared, Busker Busker had been awake for nearly two straight days.

“We told ‘em, ‘We’re not getting on that bus.’ And they said ‘No!’—they’re all friendly—‘No, just sleep on it, we’ll talk tomorrow,’” Moore says. “And we said, ‘We’re not getting on your bus, and we’re not going inside that house. We’re taking Dani back to Cheonan.’” Jang and Kim were also steadfast, though Moore thinks they may have followed orders had he not resisted.

Finally, they ended the sunrise standoff by calling a taxi. After the hour drive south they dispersed home, and slept “for three or four days, just crashed.” The other contestants, who had entered the mystery mansion, were served a new set of contracts upon arrival, and conscripted into another lengthy lockdown for “idol superstar training” on an “after-show” season. Superstar K’s second place band made for a conspicuous absence, and Korea’s message boards were soon flush with rumors and adulation for these unprecedented “rebels” of the K-Pop industry. Moore maintains they simply wanted to rest.

But as recent reinitiates of the real world, the boys still hadn’t really experienced the gravity of their newfound fame. That all changed after they resurfaced from their half-week hibernation, meeting at a local mall to exchange an ill-fitting cap Moore and Bacon had gifted Jang. Within seconds a seething throng of ravenous teenyboppers materialized, and their terrified targets had to sprint the two blocks back to Moore and Bacon’s apartment for safety.

There was little time to catch their breath. The bigwigs at CJ had been disgraced on national television by Busker Busker’s sudden exodus, but that only deepened their desire to broker a record deal détente. Moore and Jang at first demurred, but said they’d accept on the condition that they be able to write their own songs, play their own instruments, choose their production staff, and record in Cheonan—some 50 miles and several worlds removed from K-Pop’s Gangnam District helios. The demands were unprecedented for a Korean group old or new, but shockingly, CJ yielded. Even wilder was the contract’s term: a scant six months.

“I’ve never heard of anything under three years; the average is seven. And the big groups right now—miss A, BIGBANG, Super Junior—they do ten,” Moore says. “I think we just pissed them off enough that they didn’t want us in their lives for long.” Aside from the implication that CJ thought Busker Busker’s vogue would be brief, Moore thinks they proposed a quick fix largely to promote the next season of Superstar K – a demonstration that even runner-ups could land major deals.

Recorded and mixed in some three weeks on a frantic, sleepless deadline, Busker Busker 1st Album (a standard naming convention in Korea) would defy all expectations. In just two months, the album’s breezy guitar pop sold over 13 million digital songs and some 100,000 physical copies—remarkable figures for Korea’s piracy-ridden market. The record continues to surprise: this past April, the year-old hit “Cherry Blossom Ending” returned to the top of the charts sans promotion, simply because it had become synonymous with spring for so many Koreans.

But for all their accomplishments, Moore and his bandmates were typically too worn down to celebrate.

“The CJ time, those six months—I mean, it was like the TV show. It sucked. They booked us every day, all day, because contractually they could,” Moore says. His one anchor during this time was Bacon, who could now accompany Busker Busker wherever they went (one of the band’s six conditional demands). Their insane K-Pop itinerary was only exacerbated by the fact that the couple were completing their graduate degrees at the same time, coming home from press junkets and sold out arenas to peck away at their laptops. CJ tried to book them even after their contract’s June 30th expiration, but once free, Busker Busker again defied Korean norms: they canceled everything, and took a break.

The trio was by now the biggest band in the country, and liberated from the industry’s shackles after just nine months in the spotlight — an absurd windfall no other Korean musicians could even fathom. Through a scrappy and instinctual defense of their right to eat and sleep like regular human-beings, Moore and his former students had stumbled into a Kafkan castle and somehow wound up kings.

Though it hardly ever lulled, Busker Busker mania has returned to fever pitch this week: their new album debuted today in Korea, dominating the charts on all major Korean retailers. It even crashed Melon, the largest of the online stores—the first time that’s ever happened.

But this time around, things look a bit different internally: their tour schedule is cushy, their handlers can’t so much as schedule an interview without their approval, and they’ve signed an advantageous deal with Chungchun Music—in part to undo some of the reputational damage that comes with bypassing the system in Korea.

“We’re lucky to be in this position,” Moore says. “And I say we’re lucky—but we also fought for it, and made a lot of enemies to get where we are—to be happy.

“But all three of us are happy.”

Jakob Dorof inspires fan riots on twitter—@soyrev