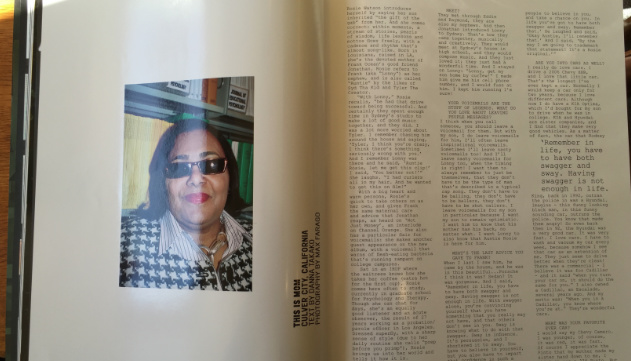

Jo Brocklehurst in Rome, 1966 (Photo courtesy of Fershid Bharucha)

A tiny woman in a blonde Dusty Springfield wig sits with a large drawing pad on her lap, sketching furiously. On her head are three pairs of glasses: a pair of spectacles resting on her nose, a pair of sunglasses over the top and another pair of spectacles above, presumably a spare.

Surrounding her on sofas and chairs in the small studio on a quiet North London street are several punks in full regalia sipping tea out of fine china. All except one, who is sitting motionless with her eyes fixed on a spot on the ceiling. She’s bemused, but delighted that the artist who lives down the street from the squat wants to draw her and her friends, luring them in with the promise of bottomless Earl Grey. She allows herself a slight smile.

Videos by VICE

This was a common scene in the West Hampstead home of Jo Brocklehurst in the early 1980s. The figurative artist, who died in 2006, is perhaps best known for her drawings of the punks who lived – along with Brocklehurst – on Westbere Road. They were part of the anarcho-punk set that congregated around the Centro Iberico squat in Notting Hill and the Wapping Autonomy Centre, putting together celebrated zines like Kill Your Pet Puppy. Crass and early Adam and the Ants were the scene bands.

Brocklehurst’s “Tension”, 1982

Brocklehurst had considerable success with these drawings, showing twice at the Francis Kyle Gallery in London in 1981/2, and later with Kyle in New York. But very little is known about her career after this, at least in the UK. You won’t find much online, apart from two national newspaper obituaries written by individuals from her inner circle. Ownership of much of her work is the subject of an ongoing legal dispute, though there are pieces dotted around London in the homes and garages of friends, including some of those I interviewed for this piece, as well as a couple in the V&A archive.

Speaking to these people nearly a decade after Brocklehurst’s death, a picture emerges of a strikingly beautiful, but immensely shy, person who lived to draw. She lived the artist’s life in the traditional sense, selling here and there to fund trips and buy materials. She was fascinated by subcultures at a time when the art establishment wouldn’t touch them. She was also a woman, who refused to paint the pretty pictures expected of her. Instead, her work recalled the taut muscular limbs and enlarged extremities of the paintings of early 20th century Austrian enfant terrible Egon Schiele. Thus, she was an outsider in the art world from the get-go, and remained so. You get the feeling that’s the way she liked it.

In a way, she was used to it. Born in England in the 1930s – she never revealed her exact age, even to her closest friends – she was the illegitimate daughter of an English mother and a high-ranking Sri Lankan politician who “had his face on a stamp”, I was told. She faced prejudice from an early age, revealing to friends how she never quite felt English enough. Patricia Buckley, an artist friend, recalls an illuminating exchange from her later years: “I didn’t know for ages that she was half Sri-Lankan. We were walking up Piccadilly one day and I said how English she looked, and she said, ‘Oh, I like to pretend.’ She had a very posh voice, like Joanna Lumley. I think she went to boarding school. Her real father probably paid for that.”

She was brought up in Dorset by her mother and aunt, and was by all accounts a superb athlete in her youth. Her passion and eye for the proportions and details of anatomy was honed at Central Saint Martins, to which she gained a scholarship at the age of just 14, and where she learned to draw at an extraordinary pace. Starting out as a fashion illustrator, she was feted by the artists and musicians of bohemian London and spent much of her time drawing in nightclubs, documenting the emerging counter-culture.

“She would never divulge her age,” says Isabelle Bricknall, a designer, artist and model, who was Brocklehurst’s muse and friend for many years. “I wouldn’t even have entertained asking her. It would’ve been totally inappropriate, because as far as she was concerned it wasn’t important. She saw herself as timeless and ageless.” Bricknall’s facial features are strong and feline, and despite her being wrapped in several layers when we meet at a pub just off London’s Old Bond Street, I imagine a muscular yet feminine figure, like a dancer. I can see why Brocklehurst wanted to draw her.

They first met in the early 1980s through Colin Barnes, the late great fashion illustrator, a mutual friend who she would often sit for. “Colin used to do all the illustrations for the couture shows. I was wearing a Christian Lacroix couture outfit, a totally over the top tweed number. Jo thought I was wild looking. She said, ‘I’ve got to draw her.’ Colin had a bit of a hissy fit and said, ‘Okay, let’s both draw her at the same time.’ His made me look like the epitome of grace and elegance, hers like I’d just escaped from an asylum. I loved both.”

One of Brocklehurst’s works from 1983

Brocklehurst started to accompany Bricknall to the London fetish clubs the latter frequented, such as Skin Two at Stallions in Soho and the early Torture Garden. The weird and wonderful characters of this fledgling scene – before “it went all reader’s wives”, according to Bricknall – were a natural draw for the artist.

“Jo had been drawing people in clubs since the 1950s. I told her where we were going and her ears pricked up. I knew she’d be game and that she’d want to be there with her pad,” she says. “She was very discreet. You wouldn’t be aware that she was there. She always wore a black velvet jacket, 70s style, the wig, the shades. I used to think, ‘How the hell can she draw in a dark club?’ But she could. Later down the line I realised she had a gift.”

Many on the fetish scene were making their own costumes. Bricknall had begun designing and making solid steel body armour with her then-metalworker boyfriend, and Brocklehurst would often ask her to wear these creations when she sat for her later on.

“I wore the first piece to the Skin Two Rubber Ball [in 1992]. I had all these strange creatures throwing themselves at me thinking it was plastic, and then realising they were impaling themselves on metal. Even then, that was funny because people got off on it,” she remembers.

Interested in fashion, are you? Check out i-D – it’s full of it.

Soon, the fashion world was taking notice. A strong fetish influence was seen in the collections of both Jean Paul Gaultier and Thierry Mugler at the time.

According to Bricknall, the earlier punk shows at Francis Kyle Gallery, though successful, had left a bad taste in Brocklehurst’s mouth. She was able to pay off her relatively modest mortgage but felt her work had been under-valued and misrepresented. Speaking now, Kyle sees it differently: “Jo sold well. We probably didn’t charge enough money, but I always took the view that if you’re showing an artist, it matters equally to both of you that they make a living from it,” he tells me down a crackly phone line from Suffolk. When I ask why they didn’t work together again, he says: “She simply said that she had new statements that she wanted to make.”

Soon after this, Brocklehurst began to spend more time in Europe, especially Amsterdam and Berlin, where she was held in high regard. “If you’re going to succeed in the arts in any shape or form, sometimes going abroad is easier, because you’re an unknown quantity and you’re celebrated much more than in your country of origin,” says Bricknall. “She liked Berlin because it was very punk in a lot of ways; it was before the Wall came down. There’s so little known about her here, but in Germany and Poland at the arts festivals, they all knew her. She played artist in residence – she’d be sketching on a daily basis for newspapers such as Berliner Zeitung, drawing different acts from theatre to art. She also made some very good friends in Berlin, some really out there types of people.”

Some of Brocklehurst’s works (Images via Kill Your Pet Puppy)

She also made frequent trips to New York, staying there for extended periods. It’s been difficult to trace her associates in the city, but from what I can gather she was involved with the Guerrilla Girls, the feminist art collective established in 1985 as a reaction to perceived sexism in the industry, and became friendly with Keith Haring, the late activist artist.

In London, Brocklehurst had, for years, been regularly attending costume life drawing classes at Saint Martins as a guest. Sue Dray, a student there in the early 1970s, now the course leader of BA Fashion Illustration at the London College of Fashion, remembers “a small woman behind huge drawings… getting exactly what she wanted from the model. She was very much a feminist, with a strong opinion about women’s roles as artists and how we were recognised. I think that’s why the drawings were so brutal. We weren’t going to romanticise anything about the models. It was about extracting character. She was working in a period when the subculture was still the subculture.”

From the late 1990s, Howard Tangye, then-head of womenswear at Central Saint Martins and a close friend, invited Brocklehurst to teach life classes with his students. Inside his house-cum-studio in Hornsey, several Brocklehurst pieces sit alongside his own artwork. “She’d had a lot of hard bumps,” he says. “She wasn’t quite the pure English rose, and I think she copped quite a bit of prejudice.”

He describes her as “extremely beautiful, mesmerising, but incredibly self-conscious about it. She would do anything to make herself not beautiful.” There were boyfriends, some serious, but she remained unmarried, though she did express regret in later life at not having had children. She enjoyed teaching, he says, and the students responded to her.

Towards the end of her life, Brocklehurst was curating a museum of her own work at Westbere Road. Though she owned the house, she was far from well off – though unhesitatingly generous – and lived very frugally, skimping on heating and making home repairs herself, as Tangye remembers: “Once, she’d built a little extra bit on to the back of the house, and there was a huge hole in the roof. When it rained it was like someone had a shower in there. I bought this big tarpaulin and we secured it on the roof, to at least keep out the water. She wasn’t bothered about it. I was up there and we were trying to fix this tarpaulin, and this great wind blew up. We had enormous fun trying to fix this thing on the roof. Then I convinced her – I said, ‘Jo, I want to buy a couple of your drawings.’ I bought two of her drawings, and with the money she got the roof fixed. She didn’t save up money – her life wasn’t about that.”

“She didn’t give a shit about impressing people,” says Bricknall. “Her sketchbooks were like her diaries. She drew every single day. She was driven to create. I think there are a lot of great artists that can slip through the net because they’re not all about the cash. The only time she’d sell stuff would be because she needed the money to facilitate a trip. She was the real deal. She was extraordinary.”

More on VICE:

Crass’s Penny Rimbaud Doesn’t Care About Urban Outfitters Profiting Off His Band’s Name

The Notting Hill Squatters Who Declared Independence from the UK