Though Es Devlin may not be a household name, it is impossible that you haven’t see her work. The multi-award-winning stage and costume designer is easily one of the most prolific (and vital) artists working in live music, theater, and opera.

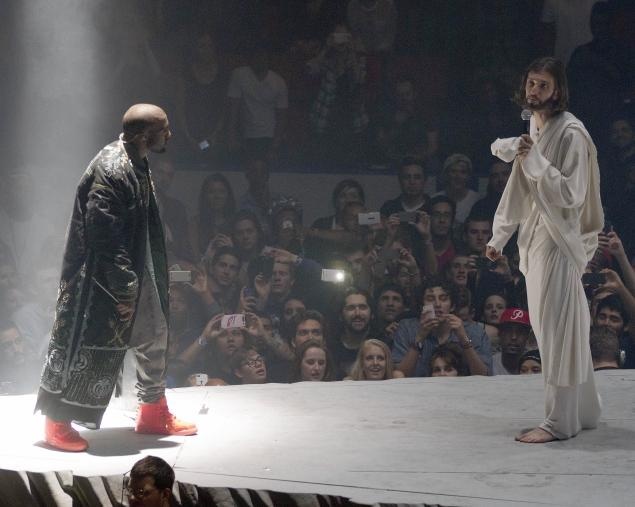

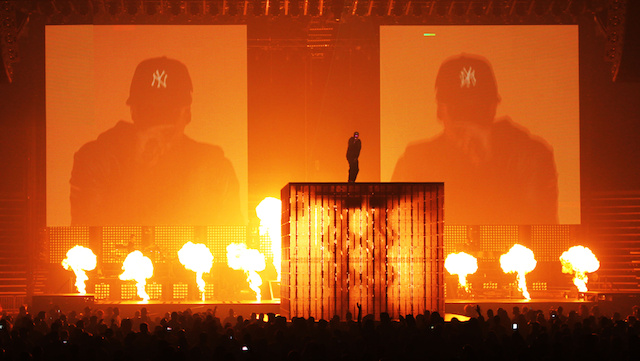

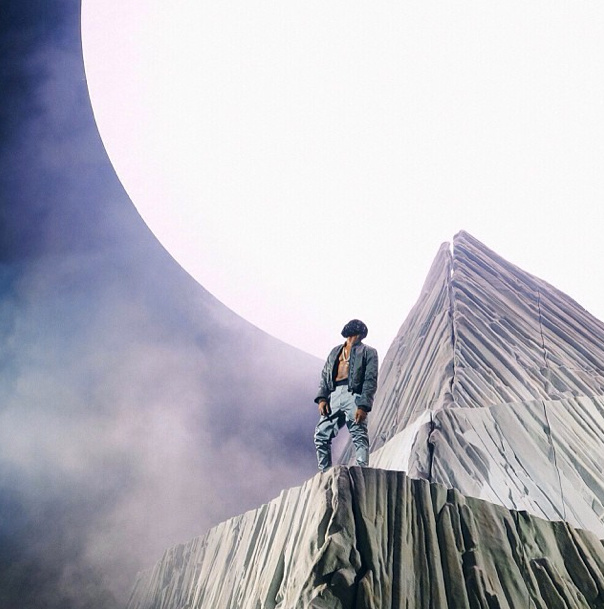

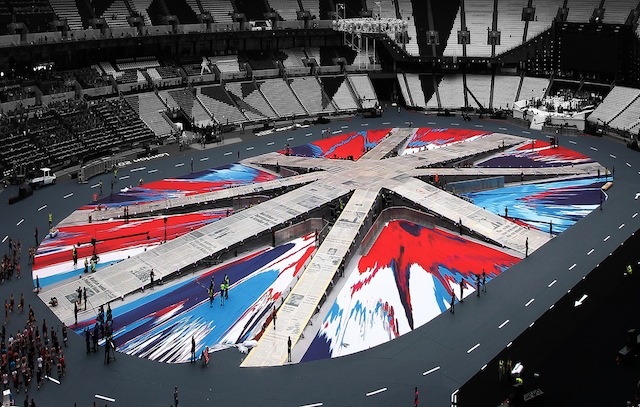

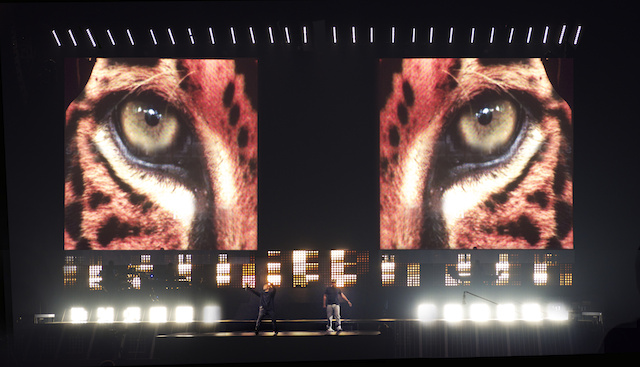

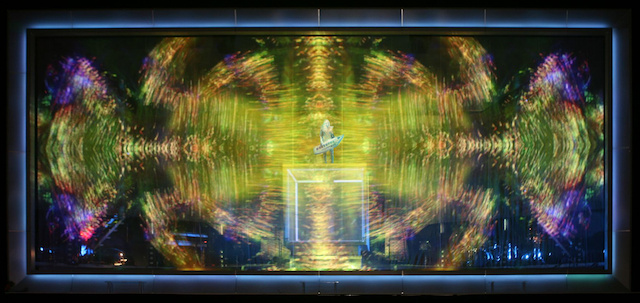

Those giant LED cubes that Kanye and Jay-Z stood on during the Watch The Tour? Es Devlin. The set design for Lady Gaga’s “pop electro opera” aka The Monster Ball Tour? Es Devlin. The cars that the Spice Girls stood on during their reunion at the Olympics (a performance that culminated in a field projection of a British flag exploding)? Es Devlin-—in collaboration with Damien Hirst.

Videos by VICE

Not only has she been integral in the stage design for mega-concerts by Kanye West, Lady Gaga, U2, Muse, and countless other world-renowned bands, but she has found an intersection between pop arena tours and small theater and opera production–often incorporating technology and groundbreaking design techniques from one to the other. This had led Devlin to become one of the go-to figures in performance design, and she has operas booked as far in advance as 2020.

It would be unfair to say she single-handedly conceptualized all these incredible productions, as the musicians and opera directors have major influence on the projects themselves (and Devlin has a vast range of collaborators for each endeavor), but it is unarguable that she is one of the most important figures within her medium, yielding pop culture-defining iconography (the fake mountains at the Yeezus tour, for example) and a new understanding of how far we can expand the boundaries of live performance and spectacles.

Devlin has been called one of the 100 Most Powerful Women in London by The Telegraph, delivered a TED Talk, and continues to evolve how we experience real-time art and performance. She just finished working on the musical adaptation of American Psycho (the mind reels at a dancing, singing Patrick Bateman, outside of the infamous Huey Lewis And The News scene) and has many projects in the works in between her long-term opera bookings.

We spoke with Devlin about what it’s like to share tour director credits with Kanye West, how technology has changed theater beyond imagination, and what it’s like to have work assigned ten years in advanced.

Looking at your website, you have projects going through 2016 and further. How does this long-term deadline influence your creative process?

Es Devlin: I actually need to update the website because I have some stuff that’s happening in 2020. It’s a really banal reason and I’ll answer your question in two parts. First, to give you a background to why those bookings take place—opera singers need to be booked that far in advance because at any given time on this planet, there are only three or four given people who can sing certain operatic roles that need to be sung at places like the Met. There are ranges written for an opera that the high and the low notes can only be achieved by rib cages inside about five human beings on the planet. So they get booked up.

As soon as you have your opera singer in place to sing Carmen, then you need a director to make sure the opera singer will take the job and commit to it. Then the director needs the designer to commit to the job because they’ll only do it if they have the right team. These things all get put in place due to the rib cage and the expansion of that rib cage and the brilliance of only the few human beings that can do it. It doesn’t have to do with me, it has to do with the singer.

With me, when I work on an opera project, we start now and know we’re going to open Carmen at Bregenz in 2017. If you look up Bregenz, you’ll be amazed. It’s a tiny place in Austria where all designers that I know most aspire to work. I talked to Mark Fisher before he died, and asked is there anything you still want to do? He’s designed Pink Floyd, The Rolling Stones, the Beijing Olympics, and there’s nothing this man hasn’t done. I asked, is there anything you still want to do? And he said, I want to design for Bregenz. It’s this lake. It’s the scale of a stadium show, but the lead time and application of material needed for an opera. We’re doing that in 2017, we’re doing Carmen.

We’ve started meeting already. We’ll exchange ideas now, we’ll start sketching, and the ideas will grow as we grow. Each year, the director and I will do five or six different [individual] projects, which will then feed back into our thinking about Carmen. Don’t take this comparison too literally, but if you compared us to the great Francis Bacon, I read that his gallery would literally steal paintings from his studio because Bacon would never consider them finished. And this is as close as we can get–in an art form that is dominated by deadlines–we only make something because there’s a show. I don’t evolve things in case there might be a show. I work because on the 26th of July on 2017, an audience will be there. That’s why I do it.

That’s encouraging, but you might have these giant, abstract ideas that could feasibly become realities. I know there are budgets and whatnot, but when there’s a specific deadline, does that sometimes make things frustrating that you can’t realize this vision or complete it in time?

That’s where the genres behave differently. In opera, the deadlines are always years in advance. And there’s pretty much nothing you can’t achieve in a year, I think. Even if your budget isn’t huge–you can do whatever if you apply yourself and find the right people.

It becomes irritating when you’re asked to do a small, TV performance for a very big artist, and it’s happening in two weeks’ time. For the very big artist, two weeks is a lifetime—like for Jay-Z, anything’s possible within a day. But, for me that two weeks becomes a custard pie in my face. It’s very hard to do anything brilliant within that timeframe. I don’t think the thought process happens right. I don’t think everyone has enough time, everything just gets thrown together, and it can be unsatisfying. I think deadlines are great, but there’s a cut off point: anything less than three months lead time is panic.

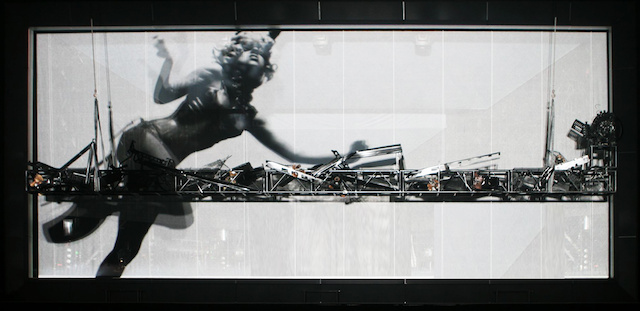

A still of The Spice Girls performing at the 2012 Olympic Closing Ceremonies.

I’ve heard you say in lectures that your collaborations with artists are kind of like this metaphorical dance where your feet are painted and you dance on a stage, and the resulting trail is the ultimate collaboration. If it’s you and this one artist, say Lady Gaga or Kanye West, what other elements are essential to this metaphorical dance? Technology? What adds to this beautiful trail?

I think that’s a really, really pertinent question. If I were trying to extend that metaphor, I’d want to talk about the production managers and the crafts people and the lighting designers and video designers.

I mean more abstractly—in these massive collaborations between a huge artist like you and a huger artist like Kanye West—would the other countervailing influences be the internet, technology, who else are these big forces that yield these collaborations?

That was part of another talk I gave, which was about dancing with people you don’t know. It’s a delicate subject. It’s really delicate. It steps into the territory of: Whose idea is it? When I do meetings now, in a room full of House of Donda or whoever and they are much younger, the Macbook might as well be the Google Glass, it might be implanted into all of us.

The metaphor I use is that Googling something is part of the thought process now. It’s quicker to do that—that your fingers become extensions of the dendrites and synapses in your brain—than to walk into the street and take a photograph. I gave the example that if I wanted to show somebody a picture of a tree that’s in a park two blocks from my house, I would Google it before going around the corner. Not because I don’t like fresh air—I spend a lot of time outside—but when you’re in the mode of thinking, and when your thought process is ticking and you just want to jump from this to that, and maintain the flow of thoughts from one to next, using the computer is the fastest way to maintain the train of thought.

You’ve been working in stage production for almost two decades, in what ways has technology changed and allowed you to either widen your craft or expand it into the future?

When I began, I was bored by a lot of theater. I was into music. I was bored by music concerts visually, too. I was visually unexcited and not fascinated by theater because I found it very old fashioned. Opera I found exciting because opera designers were beginning to do something more abstract. Then, in the early 90s I started seeing people begin to use projection, and begin to envelope film and theater together.

What I started to think about was instead of the ways things were normally done–you’d have a piece of theater and something gets projected on it—what if you had a movie cinema and then occasionally real actors step through it? That was my real fantasy. You would create a screen that you could watch a film on, and engage with it as an audience engages with a movie—wholly believing and buying into the illusion of a three dimensional surface on a plain, 2D projection. But then you could literally open a door on it and there would be a set and you could engage with people sculpturally. That has come to pass.

We couldn’t at the beginning. We couldn’t get bright enough projectors to balance with the lighting. It was impossible, but now we can. And we can projection map, and we can project on to sets and people, and we can put cameras next to projectors so that they know where the pieces are moving to. We use D3 which is a great projection mapping system that knows exactly where a piece of scenery is. We can look at everything on a screen and plan it out before we even go into the theater, which makes things more efficient.

I’ve found that technology is advancing much more quickly in pop than it is in theater, just because of the budgets involved. So things I’m learning in, say, my collaborations with U2 and my collaboration with Kanye—I’m taking all those things and those people and ideas back into the Royal Opera House, or back into the Met. I’m finding that the people who collaborate with me on the pop stars are thrilled to get their hands on a juicy, one-year turn around opera. I’m working with an amazing animator called Luke Halls who’s worked on pop animation with me on a Lady Gaga tour and everything else. Now, he is embedded deeply in my opera family.

That must be exciting because technology changes so fast that you may be able to implement something brand new into these far ahead projects like the operas.

That’s right, we even have time to actually create technologies. In these timeframes you can adjust the technology. The problem with the operas is that a lot of time you don’t have the budget. So what often happens to me is that I have two weeks and a ton of money, or three years and no money. So my kind of practice is to weave from one to the other. And what I’m finding is that there are a lot of like-minded individuals. There are a lot of people who gain sustenance technology-wise and financially from the large-scale commercial projects and then are happy to shift and come with me on journeys that are perhaps not so well paid, but have the needs of an extraordinary libretto or score like Don Giovanni or Carmen. Although ultimately I see the material as being of equal weight.

Do you have plans to use anything like wearables in the future—LED dresses, or some types of technology that you would love to incorporate into your work but haven’t had the chance yet?

The LED Dress is an interesting one, because we started doing it in 2005 with Kanye. On almost every project I’ve done, the artist has wanted to wear some LED. There’s this amazing designer named Moritz Waldemeyer who was working with Imogen Heap on her extraordinary gloves and a glowing headdress she wore at the Grammys. That was great–but I don’t suppose (yet) that I’ve made an LED dress that I’m happy with. [Editor’s Note: The Creators Project wrote about Imogen Heap’s gloves here]

All my LED dresses and projects have been somewhat disappointing. They never really show up great on stage. They’re great when you film and photograph them, but I’m yet to see something that was truly powerful enough and really delivered. I think Gaga’s stuff—and Moritz worked on that with Nicola Formichetti—and that was amazing. Anyway, I’m still waiting and hoping we’ll create an LED costume that I’m truly impressed by.

So you’ve worked on the tours for Watch The Throne, Touch The Sky, and then Yeezus, which are all are so massive. It feels like you keep outdoing yourself. How do you feel about the Yeezus tour compared to your previous collaborations with Kanye? And how do you balance the massive set with the massive pop persona? How does one not over-shadow the other?

The first thing to say about Yeezus, compared to the other projects, is that Kanye is obviously evolving as an artist every day. His relationship to his design team is also evolving. He really is the director of every decision and one has to say that. For Yeezus, Kanye and I had been talking about mountains, and we did a thing for the BET awards in 2006 that included a volcano he stood on. We had been talking about mountains since 2005 and icebergs for the past two years, and during all of Watch The Throne we talked about icebergs and mountains.

And I remember during Glow in the Dark he came on stage with that winter wonderland backdrop.

That was also with the residence he did at Atlantic City last year. That was going to be mountains and icebergs. So he’s had this in his mind for a very long time. And there’s a singularity to his vision. Although his music is the most electronically modified thing you can imagine in some sense, what he responds to visually and emotionally is pure nature. He would sing out on a glacier if he could. If you could plunk him in wilderness, or on the moon, or on a glacier, or at sea, or out on the Serengeti Plains—that’s the space that accommodates his music and makes him feel that he has the proper environment to fit his music.

Everything about the raw corporate, sports arena space runs contrary to that sense of the natural and real and soulful ideas that Kanye celebrates. From the beginning of Yeezus, we were really picking up where we left off with Atlantic City and Watch The Throne that we weren’t able to do or were appropriate for that joint project.

Do you feel like this is your biggest success of your collaborations with him?

I don’t know about that. I think what I can say about it is that it’s him pushing the medium at the edges of its form, as he’s doing with the album. It’s him pushing it like a blind person pushing up against a wall in the most brave, heroic way. It’s the most heroic endeavor. The fact that he comes out on stage with that mask on and behaves effectively as a performance artist is the most consummate achievement of weaving performance art, installation, music, and all these media together. It’s an ambition we’ve had since 2005, and this might be the consummation of that ambition.

It will be interesting to see where you’ll take it next, as I assume you’ll still collaborate in the future.

I hope so.

You just collaborated with Julie Taymor on A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Although she has plenty of theater experience, do you notice a difference between working with someone who’s distinctly a theater director and someone who’s worked in both film and theater.

The answer, absolutely. That particular space—because it’s on three sides—is a very sculptural space and great for a film director. I took photographs of that piece, and we learned a lot just through taking the photographs. And I believe what Julie’s going to do now is film it. She has a remarkable imagination and a remarkable tenacity and efficiency of preparation which I really appreciate. One has to have the instincts and see it. She’s really got the craft to be able to be able to bring things into being.

I think what her film head brings to the project is an extraordinary level of detail and preparation so every costume, every makeup design, every lighting stage–she’s really seeing it. And she’s only done about ten projects. Each one legendary. So, there’s me doing 100 projects by the time I’m 40 and then there’s her in her sixties with just a few ones that are each iconic.

Each one takes a few years to make and she’ll only do that one, but she’ll make sure it’s perfect. I greatly admire the fact that she makes each decision with the certainty that these decisions will be there for posterity. The film maker’s approach is comparable to that of an architect: When you design a blueprint you’re doing so with the knowledge that it will endure for 2000 years or however long. But I think that there’s humility as well as hubris in what we do as theater makers: The humility is that it’s ephemeral: we make a play, or a piece of theater that’s gone when its run is over. The only trace that remains is the photographs.

What is it about the presentness and ephemeral aspect of theater that captures you, compared to something on film?

There’s a few things about it. I love watching films. I adore watching films. There’s nothing I like more. I love being lost in a film. Films affect me very strongly. I get very lost in it, but part of that is because I don’t make them. If I did I would be sitting there, analyzing the crafting, thinking about how they put this there and that there and why they chose x/y/and z shot.

There’s a hubris aspect to my own pure ego that I don’t do them. The production designer of a film doesn’t frame the picture, I think that if I were going to make a film I would want to direct, edit, or be the DP. I want to be the one forming the picture that the audience sees. It doesn’t appeal to me to make an environment, some of which may never get seen.

With theater, your work is the star in a lot of respects—your vision is what the audience experiences and is engaged in for two hours.

I wouldn’t say the star–of course there are actors and singers around, and I certainly don’t overshadow Kanye West!

But your creations are what get people immersed in the theater environment.

I think there’s two things–it goes back to how we want to live. Part of what informs all my work now is that I have two small children. If you have two small children, anything that takes you away from them, or makes you miss a day in the life of an extraordinary three-year-old has to be something that you felt was a very valuable use of your time. There’s a real urgency and importance to any day I spend away from the kids.

And there’s also a quality now more than ever of being in a theater or a stadium with a lot of other human beings all focused on a number of other human beings all offering you something, some kind of ritual. I think that it’s getting to be more and more unlike anything else we do for entertainment. We do spend a lot of our time communicating as you and I are doing—through a screen. We do spend a lot of time interfacing with a lot of information. Just the fact that you have your phone off and you’re sitting in a room for two or three hours in utter concentration and immersed in a world which is there before you and is only happening then.

If you think about what goes on with performance, what it takes to be an actor delivering a piece of Shakespeare or being Jay-Z and getting up there remembering all those lines, it’s crazy. The fact that you’re in personal connection with that, and that you’re with a community of people feeling it at the same time is very, very important to maintain our identity as proper live animal human beings, especially as we get more discombobulated and rarified into cerebral human beings via virtual connections.

You’ve had so many projects, but which one would you say is the one you’re most proud of?

That’s a really difficult question to answer. Maybe the Olympic Games. Although there were a lot of other people’s ideas which I was engaging with, and they weren’t all things I would have wanted to do–I had to find my way through things. Just the scale of that project and the fact that everyone in the country was watching it: To be part of something that communal, to feel like you were working on behalf of your ‘felllow citizens’ in some way, and we were kind of responsible for representing a whole group of people. That felt important.

What about the musicians? Which tour was the most engaging or magnificent.

That’s even harder to talk about then talking about the Olympic Games! They’re all my friends. I don’t want to single out one artist because going back to the dance of brains and minds, I feel that it’s a massive privilege that someone like Kanye or Muse or U2 or Gaga would sit in a room with me and collaborate.

There’s a talk I’m preparing called ‘Diagnostic Design’ about how you engage with an artist and say: “ I’m going to collaborate with you on the design for your pop show.” What you’re really doing is a process of diagnosis–you ask what they want to say, what their lyrics are saying, what’s the message. If you’re going to travel around the world with this show for two years then what are we saying, what’s your poem, what do you want to leave behind as a message visually and sonically?

One tends to get quite deep with people. One tends to get down to the core of what one wants to say about life, and I do really feel privileged to have been able to do that with all the artists I’ve wanted to work with. Choosing a favorite musician is almost like choosing between my children—choosing between my son or my daughter. I couldn’t answer that.

Who are some other stage designers and other tours and other plays and operas that you’ve seen? Who are some people we should keep our eyes out for?

There’s an amazing company called Fura Del Baus that are from Barcelona and you’ll recognize their work when you see it, they are extraordinary. They did a project called Le Grand Macabre which is an extraordinary opera by Ligeti. They made a huge model of a woman’s body–huge–and sat it on an opera stage and revolved it. Then they projection mapped on it and pulled it apart, pulled its entrails out. It was very visceral and technical. I think you’ll like that.

Other pop shows—I saw The Wall for the first time this year which I still think is one of the best, regardless of whether you agree with what it’s saying. Just the singularity of idea–so often there’s a little bit of this and a little bit of that, but when you have something that just says, “Here I am; I’m a mountain. Or, here I am; I’m a wall.” Just the boldness or singularity of that statement is amazing and the best concert I’ve seen.

Have you ever seen Animal Collective’s live show, there’s an interactive visual element that’s pretty impressive.

I’ve only seen clips on YouTube, I should get myself to one. I’ve been keeping an eye on Skrillex. He’s been doing interesting things.

Who are some other artists or plays you would love to do the stage production for in the future?

Bregenz is the one I’m really looking forward to and that looks like it’s happening. If Kate Bush would ever decide to go on tour then I would be there in a second. We tried collaborating with her on the Olypmic Games and she did make a video but she wasn’t happy with it. She re-sang the song and re-recorded it.

I just did a musical version of Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho, and you should check it out. It will be coming to America. What’s extraordinary about that is that we have this music director, this arranger named David Shrubsole on board and he’s taken Phil Collins’ “In The Air Tonight” and turned it into a Gregorian Chant in the play. You’ve never heard anything like it. It’s ridiculous.

What I would really like to do would be to introduce David to some of the pop artists I collaborate with and to see what might ensue: I could imagine a kind of Oratorio-—something really musically ambitious. I think the idea of turning people’s pop songs into a musical is kind of played out, and if the artist isn’t singing then it doesn’t usually work. But if you were really to transpose and translate a big pop song into choral music, into really complex and fascinating layers of choral music, then something extraordinary could happen.

Images Courtesy of Es Devlin

Zach is the bomb and he’s on Twitter – @zachsokol.

This interview was originally published on our sister site The Creators Project.