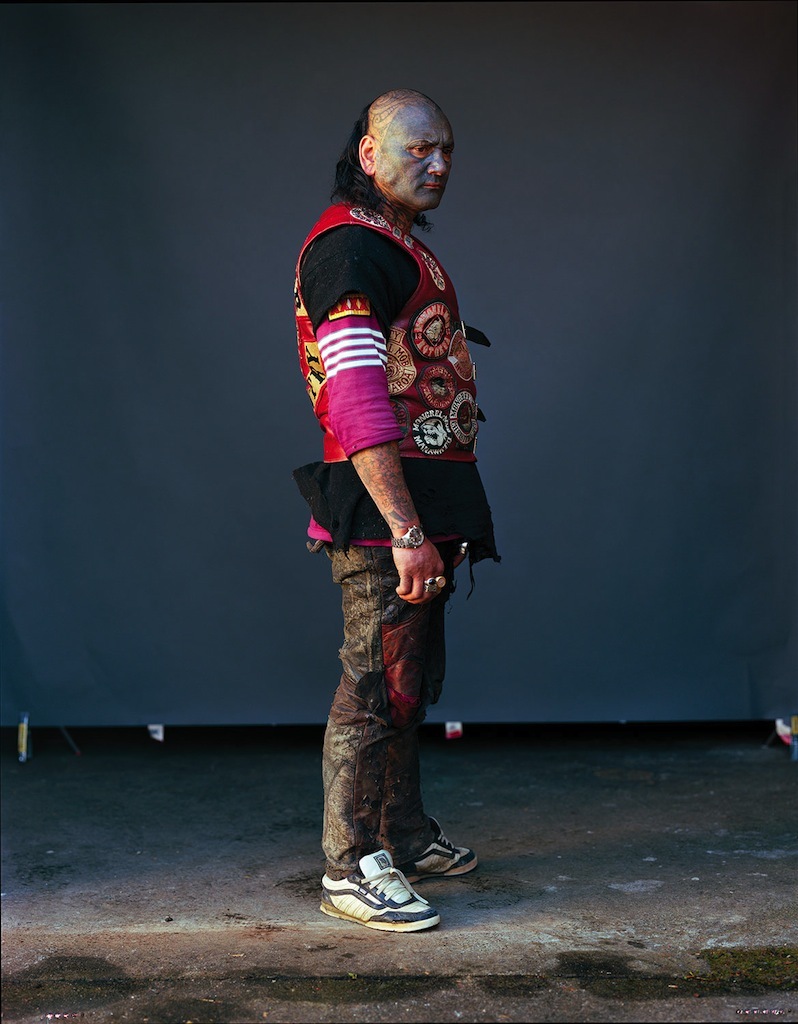

Shano Rogue, 2010. C-Type Photograph, 1.9M x 1.5M

This article originally appeared on VICE AU/NZ

In the 1960s a gang of variously disaffected youth sprang up in Hawkes Bay, New Zealand. They didn’t ride bikes, but they quickly developed all the trimmings of an outlaw motorcycle club: patches, club colours and a fiercely violent process of initiation. They came to be known as the Mighty Mongrel Mob and today they’re the largest gang in the country, with around 30 chapters across both islands.

Videos by VICE

Media access to the Mob is rare, which is why this photo series by Jono Rotman is kind of a big deal. Jono, who is a Wellington born photographer now living in NYC, cut his teeth capturing New Zealand’s prisons and psychiatric wards, before he took on gang life in 2007. We asked him how he convinced hardened gang members to sit for large format photography, and what he learned along the way.

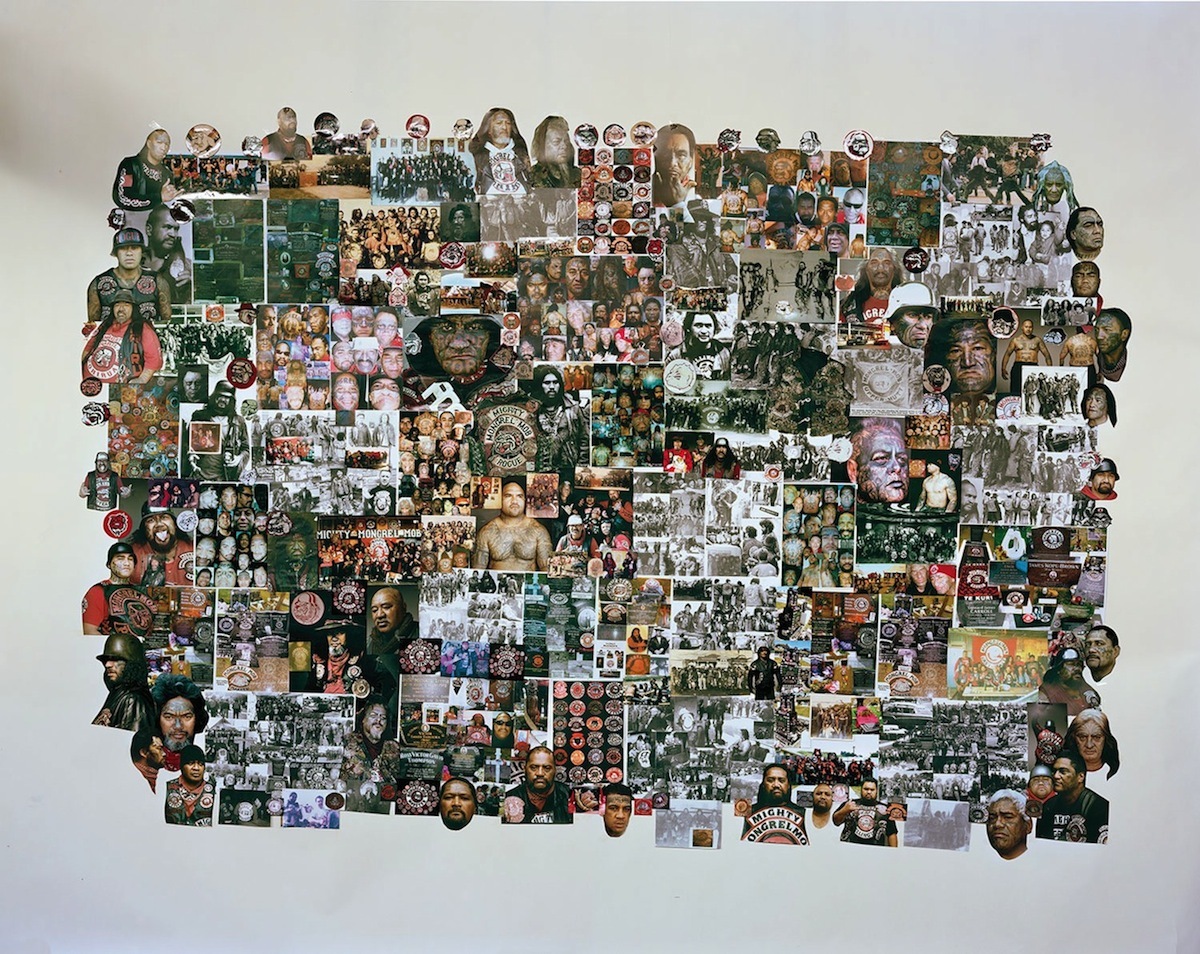

Notorious Snapshot #24, 2014. C-Type Photograph, 1.8m X 2.3M

VICE: Hey Jono, how you got access to these guys?

Jono Rotman: Initially I called the gang liaison officer at the NZ police and got a list of numbers of people who communicate between the gangs and the police. When I started it was to cover the gamut of NZ’s gangs, but ultimately I focused on the Mongrel Mob.

How did you convince them this was a good idea?

I explained that I wasn’t trying to ‘tell their story’, expose them, or some shit like that. Instead I told them I wanted to take martial portraits. And you know, regardless of where the Mob are viewed in the social hierarchy, these men have committed to a creed and fought battles, sometimes to the death. Basically the more they thought it was honest, the more they understood I wanted to produce something more complex than a cultural postcard. Then once there was go-ahead from the top, the guys down the bottom were happy to cooperate. These guys are hierarchical.

Did you feel intimidated?

Of course. Mob history is very bloody and NZ is a country with few guns so these guys don’t earn their stripes without putting their bodies on the line. Perhaps because of this, they have little to prove and are very upfront to deal with. There was always a tacit understanding that they could kill me if I fucked with them.

Denimz Rogue, 2008. C-Type Photograph, 1.9M x 1.5M

Can you describe the first portrait you took?

The first place I went to was in Porirua to photograph Denimz, the guy with the dogs on his cheeks. That’s a largely Pacific Islander and Maori area with a lot of state housing. Denimz’s place is nice though, he’s got a good family and he’s a well-organised guy. I think as they get older their outlook gets wider: it’s less about turf war, and more about the health of their community. When we met I tried to speak as directly as I could. At that stage I didn’t know what I was dealing with, so I just said what I wanted to do, and he told me what he didn’t want to do.

Sean Wellington and Sons, 2009. C-Type Photograph, 1.5M x 1.2M

Generally speaking, what are their homes like?

Their houses are pretty clean. Many have wives, and a lot of them have been to prison so they’ve come away with that regimented attitude towards cleanliness. I’ve tended to focus more on the older guys too so they tend to have their shit together. But I’ve been to some squalid dives too. In general they’re not loaded so there’s not a lot of ostentatious wealth.

And what are they like in person?

They’re pretty significant characters forged from the coalface of life. I’ve been a photographer for a long time and I’ve had my fair share of meeting the famous and lauded, but in many ways I found a lot of the Mobsters to be more impressive human beings. I’ve taken maybe 200 hundred portraits since I started. Of that, there weren’t any overly negative experiences, maybe just some teething problems to start with. Sometimes someone would get an idea about what you’re doing and, down the grapevine, it’s completely off track.

Bung-Eye Notorious, 2008. C-Type Photograph, 1.9M x 1.5M

Did you ever see anything that shocked you?

Okay, here’s an anecdote. I was on a memorial run, which is a basically a road trip to visit their fallen brothers around the country. They drive classic V8 Fords, which they call ‘Henries’, and we were 30-cars deep going through a town that was Black Power territory. That’s their rival gang.

The Black Power guys must have seen the first handful of patched cars enter the town and sent word to the guys at the other end. When we got there half a dozen guys with bricks and baseball bats came out of their lairs and started laying into the cars. And then more and more Mob cars turned up. It turned into this big brawl in the middle of the main street. Luckily the Mob chief showed up and stopped them. It would have been a bloodbath otherwise, as the Blacks were way outnumbered.

Greco Notorious South Island, 2008. C-Type Photograph, 1.9M x 1.5M

So when you look back at the eight years you spent with the Mob, what have you learned?

It peeled the lid off the NZ I knew—some of these guys are from serious poverty and from some fucking difficult environments. That’s helped a lot in understanding my country. You don’t tend to join a gang because you had access to good schools and all that sort of stuff.

As an artist I’m most interested in distillations of the human condition and, to me, gangs represent a set of human drives taken to an extreme. They have a certain purity. This is what I set out to explore, and it still stands true, but as the relationship evolved the focus of the work became more complicated. It’s humbling to meet people who’ve had an utterly different upbringing to my own, and to be welcomed. It’s also an insight into the forces that have made New Zealand. These guys have played a very important role.

Interview by Julian Morgans. Follow him on Twitter: @MorgansJulian

In Wellington? Jono’s portraits are at the City Gallery until June 14

Like VICE on Facebook and have more great stories like this one delivered to your feed.

Aaron Rogue, 2009. C-Type Photograph, 1.5M x 1.2M

Toots King Country (full body), 2009. C-Type Photograph, 1.5M x 1.2M

Breeze Notorious, 2008. C-Type Photograph, 1.9M x 1.5M

Zap Notorious, 2008. C-Type Photograph, 1.9M x 1.5M

Denimz’ Collage #3, 2014. C-Type Photograph, 1.8m X 2.3M