This article originally appeared on Noisey UK

There have been a good few 90s music retrospectives dancing about in my eyeline of late, featuring the usual stock footage: Oasis at the Brits, Blur’s knees-up Parklife routine, Tony Blair at the door of Downing Street. The latest example was the final episode of BBC4’s Music for Misfits series, which looked at the story of the British indie scene.

Videos by VICE

One episode in particular charted indie’s journey into the mainstream in the 1990s, beginning with acid house and ending in Britpop. The pundits rolled their eyes about the “Battle of the Bands” and the triumph of bro-ish corporatism in the music industry, pronouncing Britpop the beginning of the end of an exciting era of British indie. It’s ironic, given these complaints about bro-ness, that it wasn’t until a whole 55 minutes in that we heard the opinions of a woman: the music journalist Sian Pattenden.

As a female music fan, you get used to this stuff. Your experience is often either ignored or viewed as a mysterious phenomenon. Your deep love and appreciation for a band will frequently be written off as manic hysteria, or just dismissed as a desire to shag the lead singer. The responses of male fans occupy centre stage when it comes to how a scene formed or a band was received, and their female counterparts, in the main, are portrayed as a kind of sideshow.

Even by normal music documentary standards though (which is obviously setting the bar very low) this Music for Misfits episode was extraordinarily sexist. Women artists barely featured at all, and when they did they usually weren’t thought to merit the privilege of being named. Moira Lambert, the vocalist on St Etienne’s first single, was referred to as “a girl” by one pundit, and when we got to Britpop, men pontificated while footage of Elastica and Sleeper flashed past, but the groups themselves weren’t specifically named or discussed at all. Emma Jackson, a sociologist and the former bassist in Kenickie (another band written out of the story), called this indie’s “retrospective sexism” problem. It’s retrospective because it doesn’t matter how important your contribution at the time was or how knowledgeable and involved you were, very little of this will be remembered or records in the annals—or should we say mannals—of time.

I get particularly twitchy about Britpop because this is when, after years of piggy-backing on the music taste of my older siblings, I did indeed find a scene of my own that meant a lot to me. I find it interesting now to think about what it was I, and other teenage girls like me, enjoyed about it, and the ways we used it to find out about the world and ourselves.

I find it particularly interesting to think about Pulp, who, as several experts in the doc pointed out, were something of an anomaly in that scene. They are the only band that has emerged with any real credibility from these recent retrospectives, and are seen as more serious, more interesting, more complex than the rest of the Britpop rabble. Plenty has been said about Pulp over the years, about the searing class commentary, the wit, the irony and the storytelling, the British towns imagery, but somehow, I’ve never felt my experience, perhaps as a female fan, has quite been reflected. No band of this era were more mine, and the experience of being a teenage girl Pulp fan back then was unique and often contradicted.

Continues below

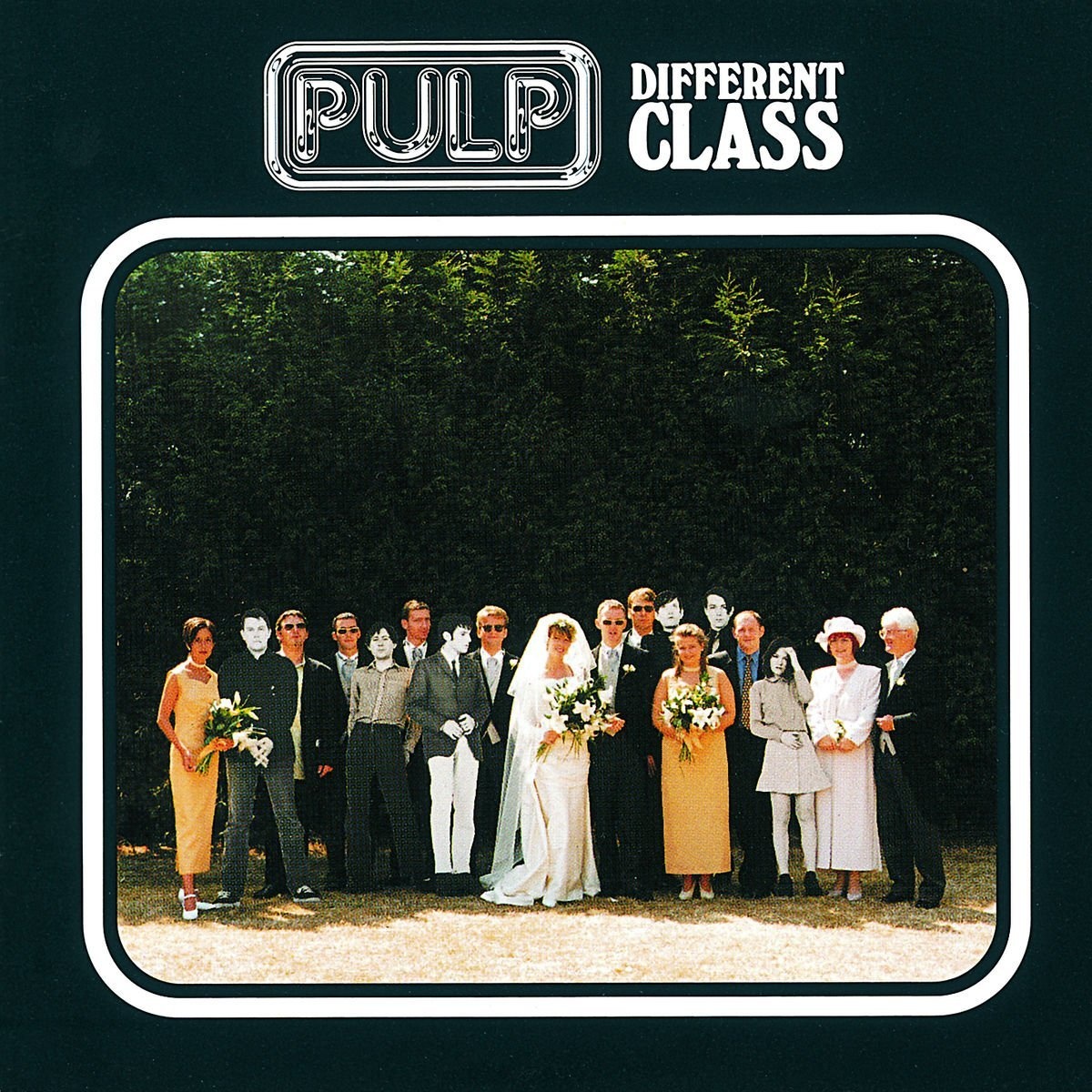

It was His ‘n’ Hers that first hooked me, in the autumn of 1994, with its sexual melancholy and tales of suburban desire. This album, along with the extensive Pulp back catalog, was enough to soundtrack my adolescent angst and longings until the following May, when there was finally some new Pulp material to buy. Here came “Common People” in all its splendour and majesty, that summer’s indie disco call-to-arms. Then at last on Monday, October 30, Different Class was released. With it, came that feeling of unparalleled delight in the life of a music fan, when a new album presents itself to you like a little box of treasure: look at all those songs!

I loved the wit and sharpness of “Sorted for Es and Wizz”, and the way it cut through the bullshit of a rave culture that I’d been too young to experience. “Disco 2000” struck me as delicious, high energy disco pop. Jarvis—brilliant, clever Jarvis—made everything seem so fun and amusing; this was a world I wanted to enter. Listening to Different Class now, it feels a little baggy and inconsistent, with a few weak tracks alongside some absolute stormers. But at the time this didn’t matter, they all seemed like distinct and perfectly contained little stories.

Yeah, sex was a big part of the appeal for me, but not a carnal and reductive desire for Jarvis himself, or any other man in the band. There was a libidinous drive that ran through those songs, a lot of which came from the lyrics, but was also right there in the music and aesthetic, in the shimmer and whirr of Candida Doyle’s keyboard, the deep, thrumming basslines, the spiky guitar. The songs didn’t need to be about sex to sound sexy, but it just so happens they often were. When, in “Monday Morning,” Jarvis sang about a dead-end life of unemployment, hangovers and chucking up on the street, it seemed somehow glamorous. Early morning comedowns in “Bar Italia?” Well I’d never had one of them, but I wanted one. There was something strangely aspirational about Pulp’s world of grubby hedonism.

At times though, something darker and more unpleasant ran through a lot of the album. Jarvis was clearly angry with women. He was in full-on class warrior mode, shown off to beautiful effect, of course, in the tale of the rich Greek voyeur in “Common People.” But a more violent side reveals itself, in which women are the locus of his fury and his desire for revenge; a weapon to be used in the war of haves against haven’ts. There’s a terrifying thrill to all this when he does it in “I Spy”—those swooping strings, the overblown hubris of the storytelling, his menacing monologues. But in “Pencil Skirt,” a song about an affair with an engaged woman and musically fairly pedestrian, it’s just plain nasty. “I only come here cause I know it makes you sad,” he sings.

To be honest, there’s plenty there to feel uneasy about in that record, but it’s a perspective I never see in these historical documentaries. As Pulp go, I have made a kind of peace with it now—by seeing it as Jarvis’s deliberate grotesquery, a character that he’s constructed to tell us something of the darkness, violence and power play in sex and relationships. And while at times he’s got a kind of beautifully searing righteousness, he’s certainly not setting himself up as any kind of moral or ethical figure, and this tension is surely where part of his appeal as a songwriter and performer lies.

Don’t get me wrong: I know we don’t look to our pop stars for political purity, but it’s worth talking about the process we go through as women when we see misogyny in the artists that we love. It’s not exactly uncommon, though it might not be something that we see straight away. I’ve found a way to continue listening to Pulp and love it, but I’ve had conversations with other women who can’t quite enjoy it in the same way anymore.

When you understand that music is still fundamentally seen as the territory of men in mainstream culture, it’s obvious why none of this is discussed properly. People like to lazily toss most music and misogyny arguments straight at hip-hop, but the list of big successful artists with questionable gender politics is a far broader than that—John Lennon? Dylan? The Rolling Stones, anyone? It shouldn’t just be brushed aside as an incidental detail, it needs to be acknowledged. As women listeners we negotiate this stuff all the time, consciously and unconsciously, and this process is mostly invisible.

It’s for those reasons that when documentaries like BBC4’s Music For Misfits write women out of history—from women who challenged the norms, rewrote rules, and changed their era, to women who bought the records, filled the gigs and formed the scenes—they exacerbate the issues and freeze progression in time. It’s like it never happened at all, and the history of music reverberates endlessly as a gaggle of girls screaming at a stage beneath the voice of some weary male talking head explaining what the music was really about.

Some amends were made by the BBC this past Friday with the airing of Girl in a Band, which looked at women rock musicians, but women’s role in all this—in making music, writing and thinking about it—should be more than just fodder segregated away for a special one-off. To make it more than this, it needs to be established as our territory, and our experience needs to be reflected, back then and right now. These discussions of the past should be flooded with the voices, stories, opinions and thoughts of women. Because there’s plenty of us out there, with plenty to say, about the thrills, pleasures and tensions of living and loving music—you just need to ask.

Eli Davies is a London-based writer and teacher.