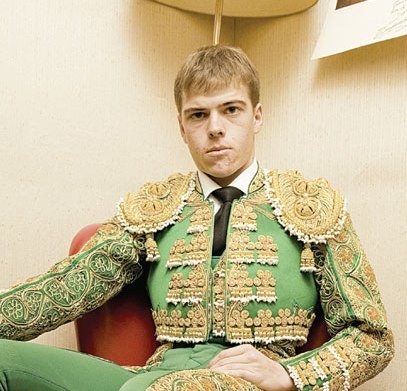

MATADOR: JAVIER CORTÉS, TRANSLATION BY PAUL GEDDIS

One of the key elements of bullfighting is the costume. Brightly colored and intricately embroidered with real silver and gold, appliqué and sequins, in Spanish they’re known as trajes de luces (“suits of lights”). The bullfighting costume is a variation on the traditional attire of the majos, 18th-century Castilian dandies who were characterized by their extravagant fashion sense. From the bottom up, a traje consists of flat-bottomed shoes, tight trousers or taleguilla, suspenders, a girdle, a shirt, a vest, a short jacket, and a tie or neckerchief. And then comes the serious part—a pink and yellow cape, used for the “dance,” and the muleta, a much smaller red cape, used in the final stages of the fight to attract the bull to its death.

Today in Spain there are no more than half a dozen tailors dedicated to dressing bullfighters, and the majority of those learned their trade at Madrid’s Sastrería Fermín. That makes this place like the Central St. Martins of the bullfighting world. Antonio López Fuentes, the man behind the business, has been dressing toreros for the past 50 years. He is as steeped in the history and folklore of bullfighting as the sand on the arena floor is in bull’s blood after a corrida.

Vice: A tailor’s shop where you can smoke? You can’t even smoke in bars these days.

Antonio López Fuentes: Whoever wants to smoke in this shop can smoke. What do you think Morante does with those massive Farias cigars he likes?

For our non-Spanish readers, that’s famed bullfighter Morante de la Pubela. So, Antonio, how do bullfighters actually go about dressing? I imagine there’s a lot of preparation, a bit like a bride on her wedding day.

Of course. Dressing a man in the traje can be relatively easy, but it does take some time. It’s even got its own vocabulary. A bullfighter can feel “bien apretado,” for example, which means that while they’re dressing, they have to feel that the clothes are fitting tightly. There are also some lovely details in the process. Tying up the machos, for example. The machos are the tassels that hang from the epaulets or the taleguilla. The public will tear these off the suit when the matador is successful enough to be carried out of the ring on the crowd’s shoulders. These are stuck on with water or saliva. This is all backstage stuff, the kind of things you’re only allowed to see when you have a deep friendship with a bullfighter and you go to dress him up in his hotel. This is a sacred, very serious ritual. The bullfighter always gets dressed in front of a mirror, and that’s where he begins to grow confident and to encourage himself, gathering the courage that he will need in the bullring. Through dressing, he can get as prepared as he can be.

Videos by VICE

There’s something feminine about the trajes, though.

Everything in it is very feminine. That’s the reason we refer to it as a dress more than as a suit. In the past, there were no bullfighting schools; the bullfighter learned in the country, no matter whether he was the son of a landowner or a simple farmhand who just happened to work in one of those huge ranches they had back then. So you had these 14- and 15-year-old boys with tanned skin bullfighting half-naked. The landowners wouldn’t be around. They were somewhere else, doing business, but their wives stayed at the ranch. Every now and then those women would throw a bull calf to the boys, just to watch them move.

So it’s all down to the female erotic impulse?

Absolutely. Those ladies ended up making clothes for the bullfighters to wear. Nowadays, a man can wear a pink suit if he feels like it, but back then women dressed the boys in unusual colors for a male. They dressed them like women but still managed to make them look manly. And today you can dress a woman in a traje de luces and she’ll look masculine to you, regardless of how big her ass is.

How does someone become a tailor of bullfighters’ costumes?

Traditionally this trade has been passed down from father to son. But sons are no longer interested, and foreigners have taken their place. Now it’s anyone with the necessary drive who is willing to learn the craft. Because this is a craft. We use very few machines, and the few we use are operated manually. In my case, my mother and all of her family were embroiderers, skilled women, who took the basic pattern of the bolero jacket and added embellishments. Our shop started after the Civil War, and it was my brother Fermín who streamlined it and made it successful. Little by little, people started hearing about us, and this reputation eventually expanded to Mexico and the rest of the world. And here we are, still. Once you’re involved, you can’t get rid of bullfighting. It’s like a poison.

In different times maybe you’d have been a bullfighter.

No, no, I’m the one who has to dress the bullfighter. If I get gored, everyone’s gored. I liked skiing back before I took over the shop, but now I don’t even allow myself that. I can’t expose myself to any dangerous activity.

If something happened to me it would leave everybody naked.

How has the costume evolved over the years? I ask because this world is intensely traditional.

It can’t and shouldn’t be modified. It’s not necessary. This business is at the exclusive service of that tradition you mention, of a certain classicism. The bullfighter is always going to face the same animal. The ceremony is always the same. And the physical factors—for example, making the bullfighter comfortable enough to dance in front of the bull—were sorted out a long time ago. The only thing that has changed a little is the style of the embroidery, but the jackets are exactly the same as they were at the beginning of the 20th century. That’s when tailors started to use synthetic fibers; before that, everything was made of natural silk. The problem with silk is that sooner or later it fades in the sunlight, and the very weight of the embroidery would stretch it.

I guess the colors of the suit have a lot to do with the ages of the matadores as well as superstitions.

Both are important, but the most common thing is to associate a certain color with triumph. Dámaso González, for example, was certain that with his cane and gold-colored suit he was destined to salir por la puerta grande [to “walk out of the main door of the bullring”—a sign of a perfect kill, but also a synonym for “success” in Spanish] in Madrid. So he ordered a new one every year. Once a matador has had success with a certain color, he usually sticks with it.

Does the embroidery imply a rank or status of any kind?

No. Well, gold does confer a certain rank, because silver is inferior. Gold means God, kings, and nobility, and for a bullfighter the embroidery is gold because he’s the king of the people. The embroidery also helps to make the chubbier bullfighters look more stylish.

And the real gold thread that everyone talks about?

It’s just a layer. It can be sewn into the suit, because the advantage of gold is its malleability. But bear in mind that an average suit, one without too much embroidery, weighs nearly 11 pounds. Gold is much denser than copper, so it would add more than two pounds to the suit. And of course it would make it way more expensive.

Do you worry about blood getting on the suits?

Blood? Blood is washed with water. Everything comes out with water. Water, water, more water! You never make a costume with blood in mind. If you did, they’d all be red.

I’m being morbid here. But sometimes I don’t know to what extent the traje is a superhero costume and to what extent a shroud.

You never think about it as a shroud. Never. The bullfighter is one man before and a completely different man after the corrida. You can perceive that just talking with them, and it’s incredible, really noticeable. A lot of things can happen in a simple matter of minutes. It’s enough for a slight breeze to move the machos of the taleguilla for the bull to see and correct his charge. The worst can happen at that moment. But no, I don’t see it as a shroud. I don’t want to. Although it does pass through one’s mind, one simply cannot think that you’re dressing a corpse.

I like the story of the legendary bullfighter Belmonte, who would cross the Guadalquivir River under a full moon and bullfight naked…

A real bullfighter is always a bullfighter, even with the clothes off. You can see that at the very moment he picks up the cape. You see it in his calmness, in his fortitude, in the way he goads the morlaco [big bull] and dodges his attack…

What’s your take on the big designers’ forays into tauromachy? Not long ago, Armani made a goyesco [bullfighting costume] for Cayetano Rivera Ordóñez. And Picasso did the same for Cayetano’s great-uncle, Luis Miguel Dominguín…

All the big fashion designers want to try their hands at it because it’s very attractive, money-wise. In this business, you can’t rest on your laurels. But this is not the world of fashion. It doesn’t have anything to do with Gaultier or Chanel. Those people don’t know how to make the chests look as magnificent as we do, and it’s impossible for them to get the embroidery right. Embroiderers exist thanks to the world of bullfighting, because the military doesn’t embroider their uniforms anymore and priests wear a simple piece of cloth as a chasuble—little more than a tablecloth, in truth. There are some trades that have become obsolete outside the world of bullfighting, so it’s totally logical that those big designers’ forays into tauromachy have never worked. It’s a secret world. To understand it you have to live it.

So who dictates the season’s trends? Is it always the best-known bullfighters?

Yes. And the first corridas, and those who triumph. When a bullfighter attains success with a certain color, the lesser bullfighters pay attention. In this world, contrary to what happens in the rest of society, the father—the master—is respected.

But customers must come with their own ideas…

They do. But when I talk with them I realize that they’re just fantasizing. They ask, I listen to what they say, then I have to explain that the thing they’ve seen doesn’t work for everybody. That said, the idea of uniforms appalls me, because the world of bullfighting is a very colorful one.

Sometimes I’ll get angry and I’ll say no to their suggestions, and I won’t budge an inch. A ribbon in the hair? Not if I don’t think it fits. A pattern in the embroidery that I’m not convinced about? I won’t make it. We’ll get angry at each other, but maybe they’ll come back some other day and start talking again.

Who’s the most elegant bullfighter?

In principle, the one who spends the most money. But it doesn’t actually work that way. In his day it was probably José Ortega Cano. Although today it has to be Sebastián Castella, for many reasons. First of all, he’s got the body. Some other bullfighters spend more money, perhaps, but nothing grows on barren land! Then again, there are some bullfighters who don’t look specially good in a traje de luces but their devotion and guts make them stand out. There are a few tricks. Knowing how to measure your steps, for instance. Or being careful with your words. Bullfighters don’t tend to be very talkative. All in all, there are men who have the art in them and men who don’t. In bullfighting, like in any other discipline, there are artists and there are those who just work the bull.

And Fermín has dressed them all…

All of them. I can’t tell you who has commissioned this or that other cape because sometimes the piece isn’t even for a professional but for someone who wants it to use as a shawl on top of a chest of drawers. We’re talking here about a piece that can take a year to make! Once a Mexican who worked in Bill Clinton’s security team came here and commissioned a cape from me. There are only two places to really get to know a man: in bed and at a bar. Of course I wasn’t going to take the guy to bed, so I took him for a few glasses of wine. In the bar he confessed that he’d come into the US illegally and that he remembered the corridas his grandfather used to take him to when he was a child in Tijuana. In Washington he’d married an American woman who couldn’t stand bullfighting, but he still ordered a cape embroidered with the Virgin of Guadalupe.

So how much will a suit set me back? You know, something simple that I can wear when I go out for bread.

That’s going to be a pretty expensive loaf of bread. A basic dress will cost you around 3,280 euros [$4,500]. But just like with cars, the cost goes up as you add extras. This or that trimming, decorations… caireles, which are double stitches in silk…

I was wondering if you’d be able to recognize one of your capes by seeing it in action. It’s not just a piece of cloth, after all—the way the weight is distributed makes it closer to a piece of engineering.

Yes, of course. Years ago the cape was circular, like a wheel, which is why in the old style of bullfighting the torero would handle the cape sideways. Eventually the bullfighters demanded that we reduce the radius of the capes. You know, very few modern-day bullfighters would be able to handle one of those natural silk capes of old. Those things could stand up on their own; you needed a healthy amount of patience and a damn strong wrist to use them. The style changed after Manolete started to do vertical bullfighting, in which the charging bull passes closer to the matador. This is exactly what José Tomás is doing now.

The first bullfight I saw was with José Tomás, and I had no idea who he was beforehand. This was two years ago in Barcelona. Nobody I knew, no one in my family even, liked bullfighting, and to tell you the truth it disgusted me. But what disgusted me more was that people tried to tell me what to think. So I went to see it for myself. At the beginning it was a shock, when the first bull was picado [speared]. But soon I got into it, and now I’m addicted. It’s hard to admit to this in Catalonia, where the overriding sentiment is “This is not for us.”

But do you think it’s really like that? Could it not be that bullfighting means “Spain” for them? It becomes a political question.

Yes, in part. But the argument against tauromachy insists on saying that is an obsolete, primitive tradition.

Why don’t they criticize the pyramids of Egypt then? Or the Lady of Elche? Old traditions have to be preserved, they have a value. You can’t build something from nothing. There are a lot of archaisms in bullfighting, true, but to me that’s valuable.

I’d like to be able to share this with people. For me it’s been a revelation, but it’s impossible. Whenever I bring it up, people get really upset. They just don’t listen.

It’s a shame about Barcelona! It used to be one of the most important cities in Spain for bullfighting. Then it all began to flag. Lesser-level bullfighters meant that the crowds didn’t have high expectations. But I don’t think the parliamentary campaigns to ban it will have any real effect.

Again, for our non-Spanish readers, let’s note that several Catalan social collectives have launched a legislative initiative with the goal of putting a ban on bullfighting in the Catalonian territory. A definitive parliamentary decision is expected to be made between March and April. But yes, I believe that bullfighting is “natural” and can’t die or be outlawed. If it happened it would have the same effect as a prohibition on alcohol.

That’s right. I don’t care whether there are bullfights or not. But I do think it’s dangerous to go so far as to put a ban on customs and traditions. If corridas really shouldn’t exist, they will disappear by themselves. It’s no good banning them. The problem with bullfighting today is that there’s no one figure charismatic enough to show the general public all the power of the fiesta.

Couldn’t José Tomás be that man?

José Tomás is special for many reasons. He’s close to his cuadrilla [team], which is pretty unusual these days. He’s generous, more than anyone could know, because he won’t allow the media to report on these things. In his greatness as a man, he sums up everything that is good about the world of los toros. The history of bullfighting isn’t just in the ring.

And he doesn’t make the sign of the cross before the bull. He’s not only attracting new followers to the fiesta because of his art, it’s also down to his atheistic and antimonarchist attitude. He’ll quote Yukio Mishima instead of the Virgin of Macarena. To me it seems like he’s brushing aside those conservative and tacky aspects that don’t appeal to certain sections of society. And through getting rid of the more conservative aspects of bullfighting he’s paving the way for a new type of aficionado.

I don’t think José Tomás is particularly anti-anything. He’s just eclectic. A guy of principle with a big heart. He’s honest, and he never bows to anyone who he doesn’t feel deserves it.

The anti-bullfighting argument always focuses on the rights of the bull and ignores the virtues of the bullfighter. What do you think about the Portuguese alternative, where they don’t kill the bull? For me that’s not a corrida.

That’s because it’s not. I’ve seen some corridas in Portugal and they’re not thrilling, there’s no emotion at all. Portuguese bullfighters don’t really goad the bull, they use banderillas [sharp, decorative sticks] with Velcro or something! They are obliged by law to do it that way, but that’s changing a tradition.

Does anything compare to bullfighting? Is there anything else as deadly serious?

No. There’s nothing like it in the world.