From the moment American Airlines Flight 11 struck the North Tower, the U.S. and much of the Western world were set on a course toward a nebulous conflict at home and abroad, called the War on Terror. The two main military engagements, Afghanistan, and later, Iraq, would sap the West’s resources, prestige and credibility on the international stage as both countries became insurgency-fuelled quagmires.

Most people reading this would have grown up with those wars – or at least, the long tail of them. The U.S. ignominiously left Afghanistan in 2021, with the scenes at Kabul International Airport serving as another sign of the limits of American world-building. Pulling out marked the practical end of the wider War on Terror, but what impact did those “forever wars” have on the U.S. culturally? The book Engage & Destroy, by photographer and artist Jason Koxvold, looks to explore that question.

Videos by VICE

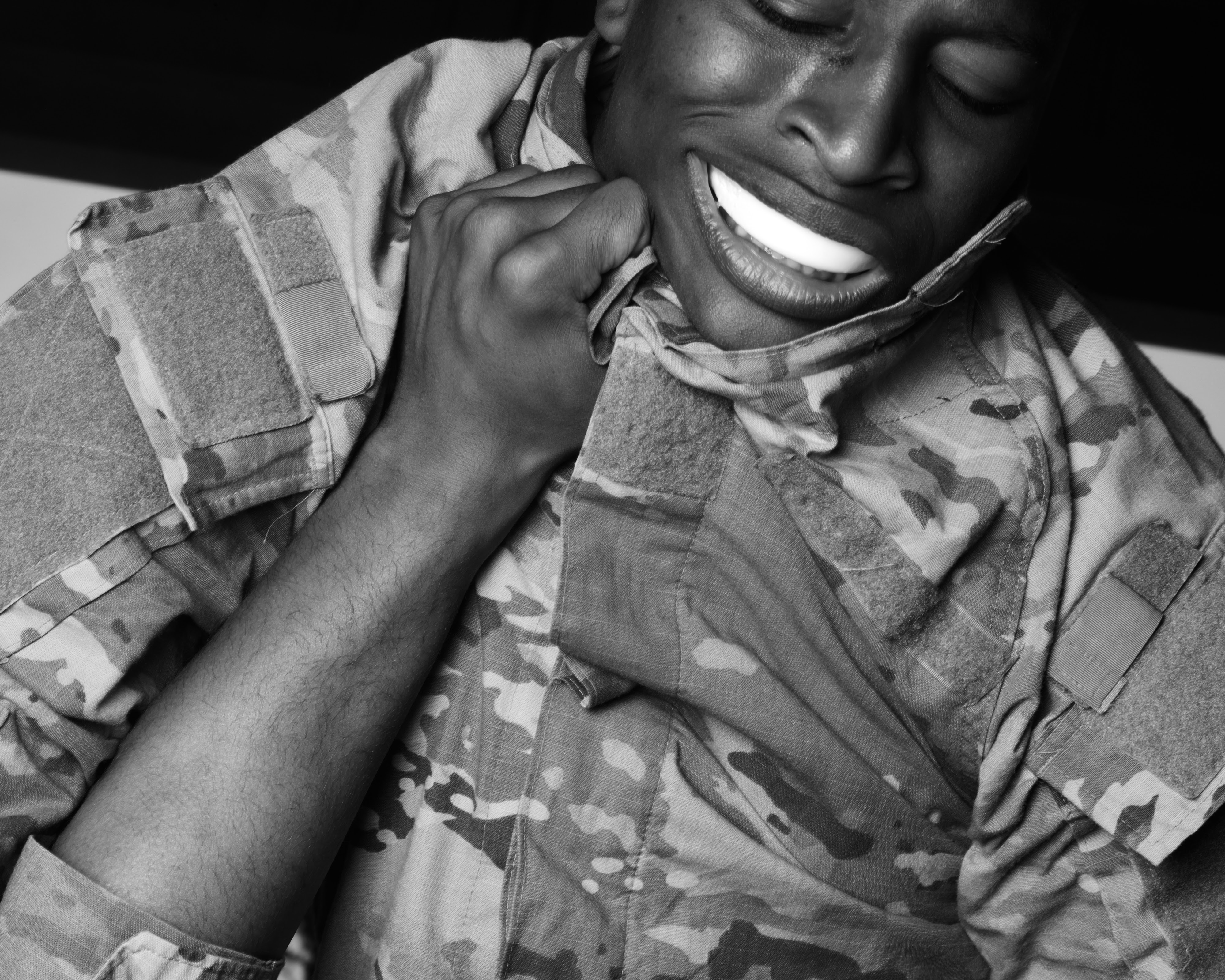

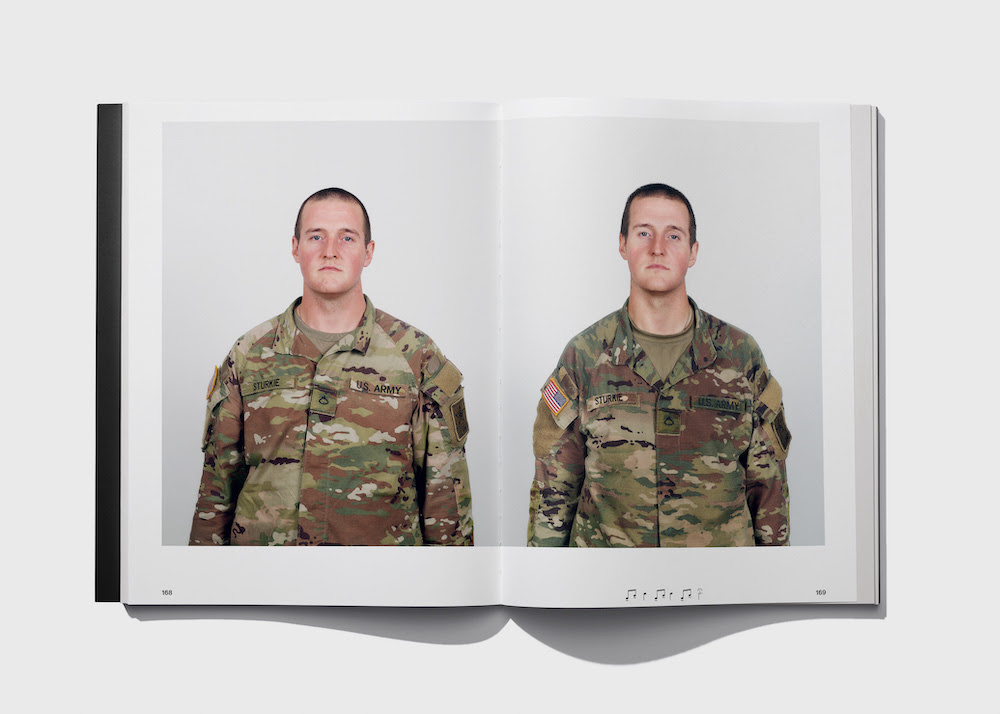

Made over the course of 16 months at Fort Moore in Georgia, Engage & Destroy is composed of portraits of male U.S. Army recruits at the beginning and end of their basic training cycle. The book also features images of the men fighting hand-to-hand, along with deconstructed words of the Soldier’s Creed, which is a standard all American soldiers are expected to live by – recruits learn it during basic training and recite it publicly on graduation. The resulting book is a searing, discomforting look at how hypermasculinity and perma-war affects the mind and bodies of new US Army recruits. We spoke to 46-year-old Koxvold to find out more.

VICE: Nice to chat with you. From what I’ve seen of your work, it’s really interesting.

Jason Koxvold: Nice of you to say so. This is a long-term project that’s been trickled out in different ways. Engage & Destroy is a small part of it. I’ve been doing stuff about war since 2015. The first time was Kuwait, and then I went to Afghanistan and UAE and then bases all over the U.S., just trying to kind of prove out this hypothesis in my mind that you can’t be at war for two decades without it having a kind of severe cost associated with it in terms of the electorate, quality of life, freedoms and so on. A lot of people in the U.S. take that for granted.

I’m part American, but I’m put off [living there] by the mass shootings. How do they fit in with your thesis about the effects of the forever wars?

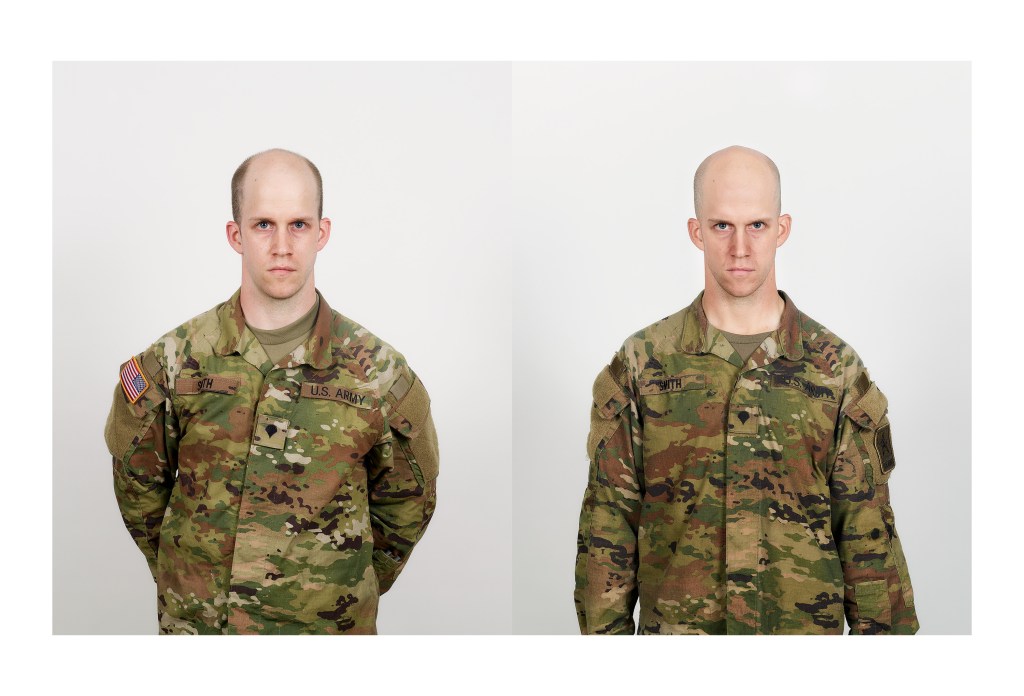

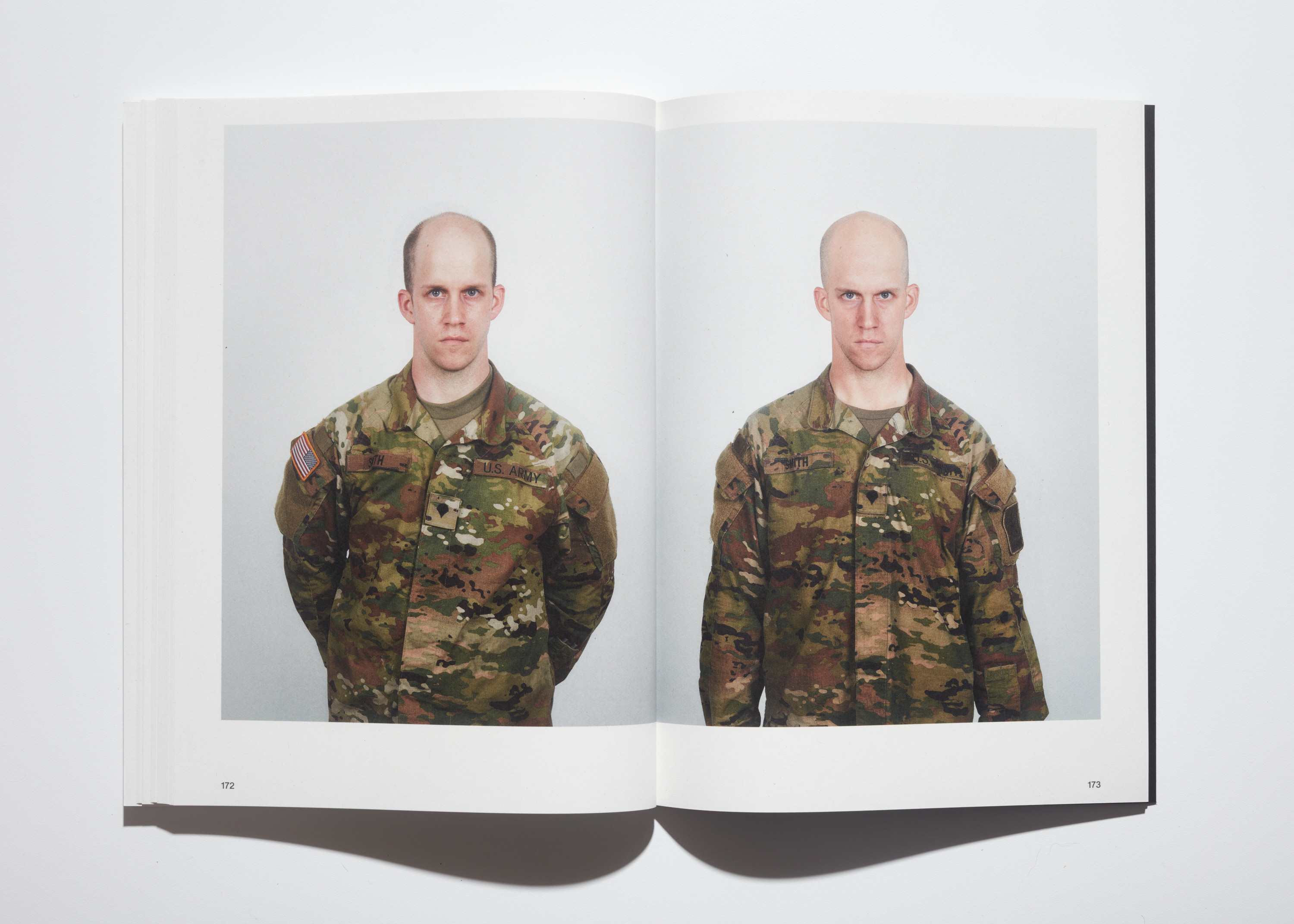

Much of it comes down to this fetishisation of war and guns. See how school shooters dress and it’s often in a somewhat tactical style using those tactical-style rifles. This idea’s very deeply connected to religion and our rights – perhaps as white men – this fantasy of the “good kill”. “The righteous kill”, a “legal kill”… I mean, look at this guy [shows an image of a recruit called Smith, below].

I knew you were going to show me that guy. There is a transformation, but it’s also how he looks in the beginning…

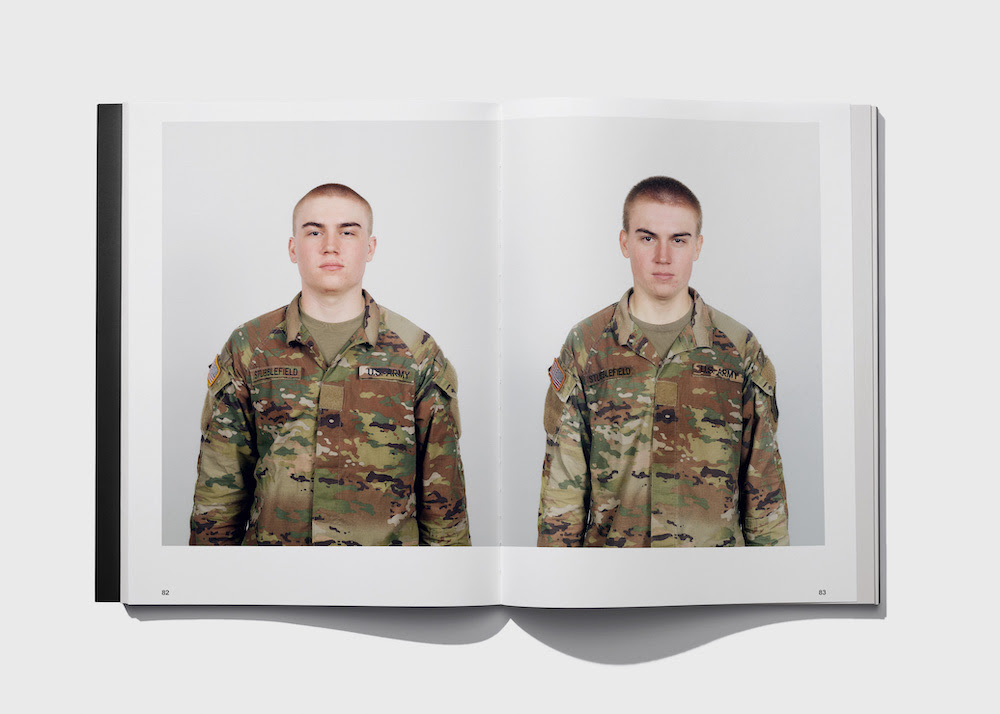

This side [left], he’s like the accountant who dreams of joining the military. And this side [right], it’s like, transformation complete. Having sat with them [the photos] for months, I feel like I really started to know them [the recruits]. One of the ones that really kind of breaks my heart is this guy Simpson, who begins as a kind of vulnerable-looking, dare I say, beautiful boy. And by the end of it, he’s just broken.

Most of the people I photographed, if you were to try and characterise their transformation: They mostly lost weight, they mostly turned from boys into men, they mostly appear to become more confident. But then there are some outliers who it doesn’t work with. And of course, there are the outliers who just didn’t graduate for whatever reason. We know they can quit. We know they can be kicked out. It’s also possible they can kill themselves or otherwise die in training.

I know there is a suicide problem in the beginning phase because when I was photographing their dormitory, on all sides of the room were bunk beds. And in the centre of the room was one solitary bed. I asked, “What’s that for?” And they said, “Oh, that’s the suicide-watch bed. If you’re suicidal, we put you there.” And my gut reaction was “Is that a good idea?”

Jesus. That’s kind of shocking, isn’t it? Is that a good way to deal with it?

Perhaps by putting the bed in the middle of the room, it’s a way to say “We care about you and we’re keeping an eye on you because we care”. But on the other side, it almost seems like shining a spotlight being like: “Look at the suicidal guy.”

I mean, in old-school, Full Metal Jacket-style training, there’s no room for mental health and feelings really, is there? The whole point is to put that to one side and become a machine of the state.

You see that in the eyes of some of these portraits, too. Sometimes they begin with a sort of curiosity in their eye. By the end, that’s gone. I think it pays to remember that these are just real people from every corner of the American experiment – you’re going to see a wide range of characters represented. I really enjoyed seeing how some of the people who weren’t born in the US were kind of throwing themselves wholeheartedly into this process, perhaps using their enlistment as a way of becoming naturalised.

We are so accustomed to treating soldiers as heroes, but in a very simplistic way, like they’re a totem of goodness. But we don’t want to engage in questions of what does that involve?

Is there anything you want to say about “culturally manufactured notions of hegemonic hypermasculinity” during these forever wars, as you put it in the book?

That guy we both noticed earlier [Smith] is a really interesting example of that, right? Like, what is it to be a man in 2023 in a culture that really prioritises this winner-take-all, might makes right, notion of just strength. And this guy [Simpson] is another great example of it, because he doesn’t fit that bill – it’s manifested in his face upon graduation.

I think that permeates a lot of different areas of American life where there’s not much room for nuance or debate. If you look at the way the presidential debates are held, it’s very much like, “I’m right, you’re wrong!” It’s just pure macho posturing. That’s what a lot of people expect when they join the military. It always kind of saddens me as a parent – sometimes I’ll see other kids my son’s age who are kind of already being raised in the punisher death cult, like they’re being raised to be little killers.

I’m busy trying to make sure my children can become sensitive, thoughtful, strong yes, but who can understand the human condition is a very multifaceted thing. Humanity is capable of being expressed in many different ways, versus this whole glorification of death – the absolute worship of all things destruction-related.

Do you feel as though this book functions as a form of protest? Is there still value in protesting?

I don’t know how big the Palestine marches have been in comparison, but I did read the other day that Iraq – if you count over the space of a couple of weeks and across multiple countries – was the largest ever anti-war protest in history. I think there’s a sense of futility these days; that millions upon millions of people around the world marched against this invasion that seems so clearly immoral and illegal, and it did nothing. It’s like, “Well, if you can’t stop that, then what can you stop?” I actually disengaged with anything about war for a full 10 years before sort of re-engaging with it again [with this project]. Are you familiar with the book by Philip Jones-Griffiths called Vietnam Inc.?

Maybe.

That book was credited with really fanning the Vietnam War protest, bringing the reality of that war home for many Americans and changing the tide somewhat. Social media has become far more of a cultural mover [now], but some small part of me wants to think that this project can help people change their opinions of war, rather than: “War: good”, you know?

More

From VICE

-

Courtesy of the Michigan Department of State -

-

-