Confessions is a series of essays on personal experiences and intimate issues, many of which have been kept secret for so long. By sharing these previously confidential accounts, we explore our own mental health without judgment and the various ways we cope, with the hope that it makes it a little lighter of a burden for us to carry. It’s also a reminder that no matter how odd or unique these experiences can be, someone can relate to it – and we are not alone.

The first time the idea for The Long Walk fluttered into my head, I waved it off. A walk around Singapore’s perimeter just didn’t seem like a good enough story. What’s the point? I thought to myself. There’s no angle.

Videos by VICE

But after both my editor and a friend raised the idea in the same week, I had to reconsider. I mulled it over, poked at it to see if it gave, but the idea stuck. I did my research. I read running blogs, checked out routes on running apps, and scanned news websites to see if anyone else had done it. It turned out that no one was crazy enough to walk the entire 150km perimeter in three days and write about it. I knew then that I had to go through with it.

The Plan

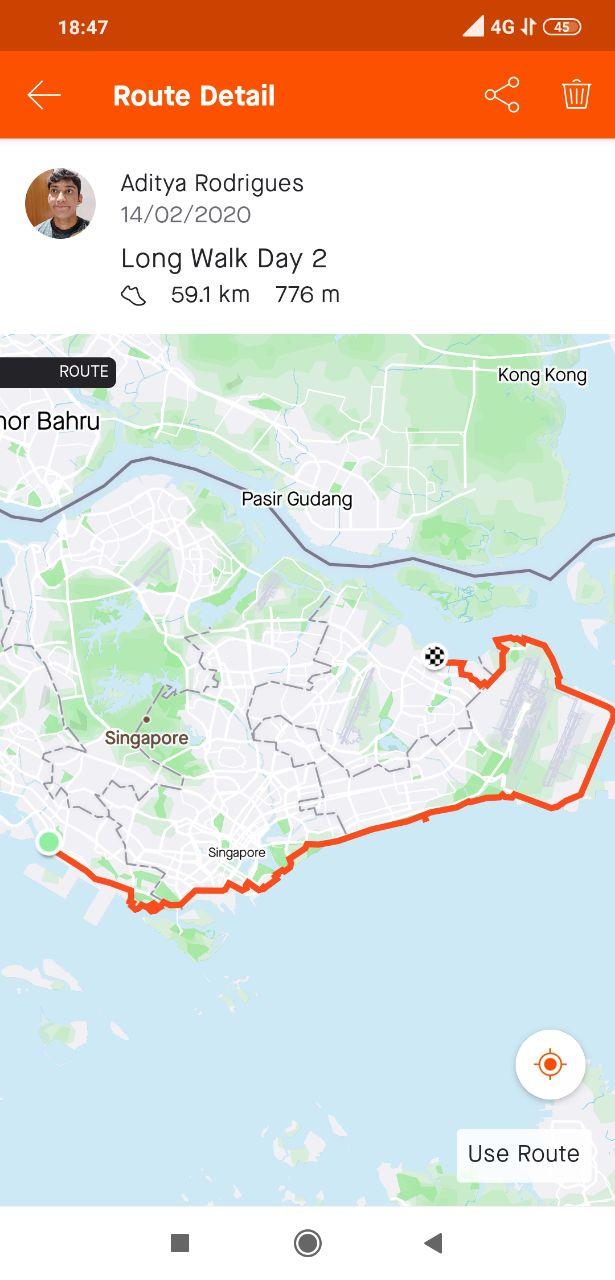

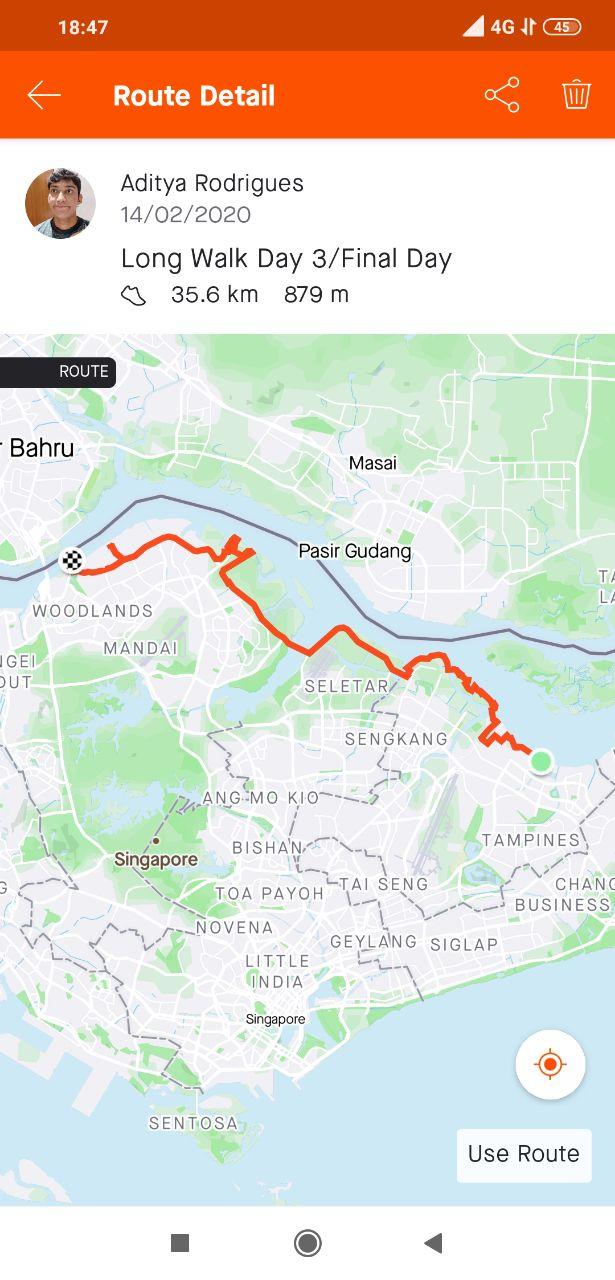

The idea was simple: over three days, I would walk the circumference of Singapore, on accessible roads and pathways nearest to the coastline, totalling 150km. Starting at Woodlands, the northernmost part of the country, I would work my way counter-clockwise.

Day 1: 52km, starts at West Coast Park where I would camp overnight.

Day 2: 60km, brings me to Pasir Ris Park on the east side, where I would spend the night at a friend’s house.

Day 3: 38km, I make my way back to the start.

It all seemed simple enough, and after doing the necessary prep work, I was ready. Or so I thought.

Day 1

The day of reckoning. After a last-minute grab of camera equipment, protein bars, and vaseline (fuck you chafing), I made my way to the starting line. I was joined by kopitiam enthusiast, car ride provider, and all-around great friend, Pravir who had been oddly enthusiastic to volunteer his company on the first day’s trek.

I contemplated what was ahead. I only had two hours of sleep the night before as giddy anticipation and some last minute preparation prevented me from getting a full night’s rest. The start and end points were at the end of a long jetty, protruding out from Woodlands Waterway Park. On it, you could see neighbouring Malaysia and the causeway.

I tried to find some poetic connection between the start of my journey and the proximity of Malaysia, but I couldn’t muster anything.

All that was left to do was start. So we walked.

The first 10km was easy enough, and before we knew it, we had reached the Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve, meandering walkways stretching around a 130-hectare mass of mangrove forests. We dismissed signs advising visitors to stay away from the water, where estuarine crocodiles lived, and edged deeper into the forest. We stopped at a clearing.

The water level was high and the wind sent ripples towards us. I saw a stir in the distance, small enough to not cause a splash, but big enough to create its own set of ripples. Then all at once, we saw a triangular head emerge out of the water. There, not 10 metres away from us, was a 2-metre-long croc, careening silently through the water with such subtlety you could miss it or dismiss it for a log.

As if aware of the eyes trained on it, the croc sunk back into the muddy mangrove just as silently as it arrived. It was humbling to witness a creature of such placidity, in its natural habitat. I looked to my right and I saw Pravir inelegantly losing his shit. The duality of life.

The next 20km weren’t nearly as graceful. Ahead of us was a notoriously long, unpaved, unshaded stretch of road. Flanked on both sides by army camps, air bases, and farms that smelled of chicken shit, there were no shops or restaurants anywhere near us. Running low on water, a ferocious rumbling in our stomachs, and only halfway into the day, we bowed our heads and for the first time, I entertained the idea of calling it in and abandoning our trek.

To spare us the indignity of passing out in the middle of nowhere, Pravir suggested taking a cab back to his car parked in Woodlands, and returning with a delivery of life-giving nourishment. I agreed seeing no other alternative. Meanwhile, I sat under the shade of a bus stop, puffing on cigarettes and trying my best not to book my own taxi back home. It took Prav just under an hour to come back with sustenance. He came out of his orange Peugeot carrying plastic bags of water, isotonic drinks, and curry puffs.

After Prav left, the rest of the day was a slog. The weight of the coming three days hung over my head, the weight of my bag dug into my shoulders, and the weight of my eyelids grew heavy.

The last 10km of the day offered nothing to wonder at. Massive industrial estates of crumbling concrete structures and twisted metal stretched out in every direction, signifying that I had reached Tuas, the western tip of Singapore.

This was a side of Singapore I had rarely encountered. Towering chimneys bellowing pillars of smoke, rising up to meet the clouds. Desolate shipyards with rattling rusted ships, grinding against each other, like shackled inmates waiting for the noose.

The entire landscape looked like a dystopian postcard. There were no soft edges in the wild west, I thought to myself.

Still, I kept walking.

At 8 PM, I finally reached the West Coast Park campsite after 12 hours on the road. Sitting on a park bench to decompress, a combination of sleep deprivation, dehydration, and intense doubt made me want to throw in the towel. The thought that I had to get up early the next morning after a night of sleeping outside, to do another 60km, was gut-wrenching. I began to construct a plan to tell my editor that I was bowing out.

The moment I spoke to her, the bargaining thoughts running through my mind evaporated. I couldn’t go back on my word or waste all the ground I had gained. It’s a story worth telling, precisely because this is so fucking hard.

Before I could spiral too far out of control, some friends came by to help with my recovery, and after an artery-clogging meal at McDonald’s, I retreated to my tent. I definitely had worse sleeps, and that’s high praise considering I was holed up in a one-man tent, using a bag as a pillow, with only a thin layer of waterproof material separating me from the grass. I had anticipated only a few hours of rest, but I slept like a log.

Nine hours later and I was back on the road again.

***

Day 2

Day 2 consisted of a trek from Singapore’s southwest all the way around to the northeast, an unholy distance of 59km. After a 52km trek the day before, it might as well have been Everest.

It was along a 2km stretch connecting Marina Barrage to East Coast Park where my right foot started to act up. Every few steps, an ache would resonate from the bottom of my heel to the back of my ankle. It had never been an issue before, but the vast distances ensured that this wouldn’t be the last time it would show itself. Half distracted by the pain, I reached East Coast Park almost unconsciously. There, I met with four friends, who would accompany me until Changi Village at the eastern tip of Singapore. This portion of the walk was scenic. A 10km stretch of coastline featuring amenity-filled park connectors, but what lay beyond this idyllic view was the stuff of nightmares.

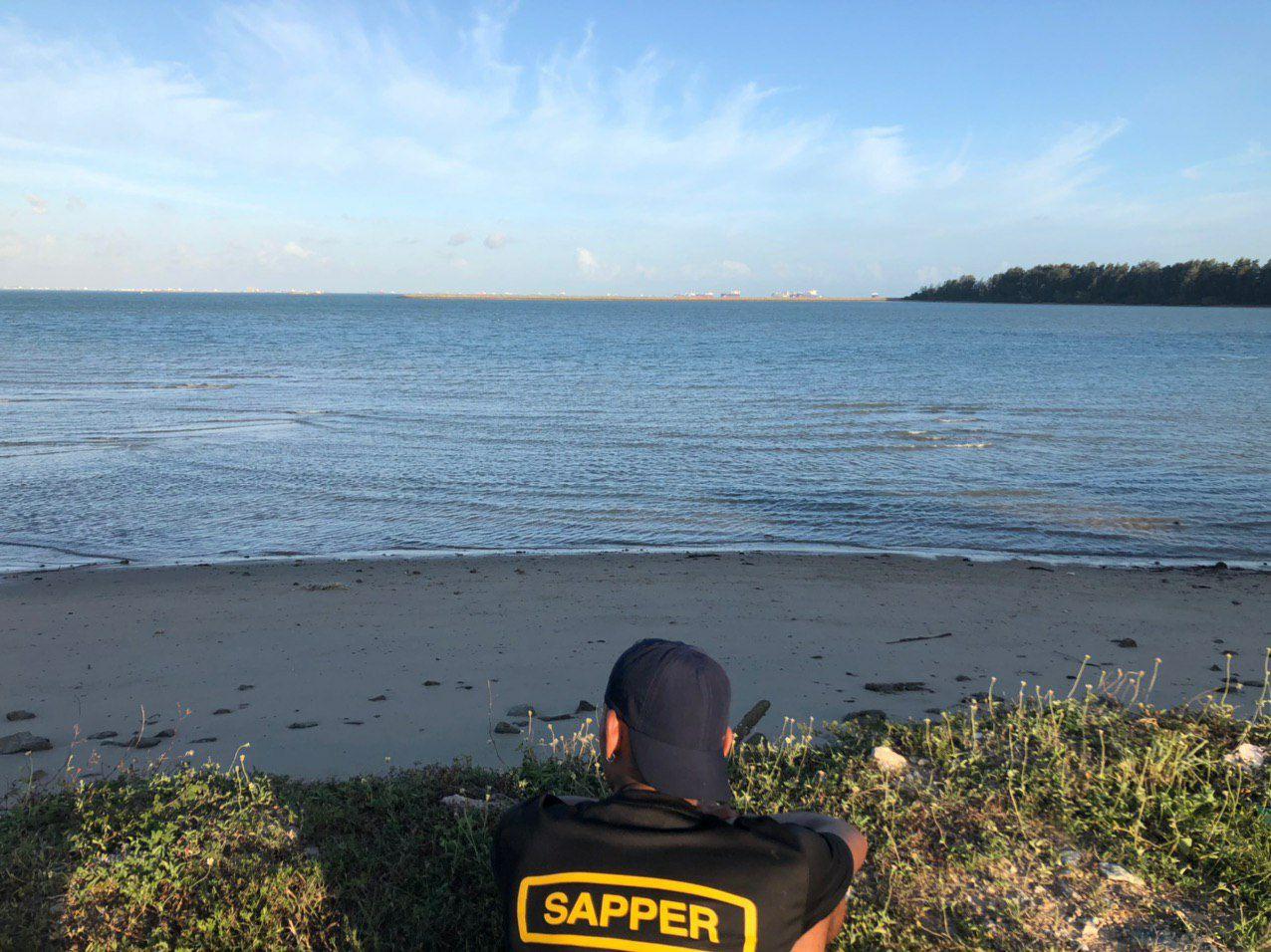

It was a hellish stretch of road, 13km long, flanked on both sides by pine trees and barren coastline. The trees at the other end of the stretch were faint grey silhouettes, and knowing that I would eventually have to reach it was a mental assault.

Every minute stretched to an hour and every metre walked like a mile. Apart from an unexpected respite in the form of a scenic beachside lookout, I and the mad lads who joined me only had the road in front of us to look forward to.

That long stretch of road took three hours to clear but, to the victor go the spoils, and at around 9 PM we reached Changi Village Hawker Centre, a precursor to the end of the day’s walk. After filling our bellies with nasi goreng, sambal stingray, and super cooler upsize (one litre of coconut water, coconut slices, and wheatgrass syrup), I knew I would have to walk alone for another 5km to my night’s accommodation.

The amount of will it took to pull myself up after two hours of resting my legs made my eyes water. It took a bargaining match with my friends to finally convince myself to get up and get going. My lack of training, preparation, proper diet, and hydration schedules were coming to a head and it wasn’t pretty.

Two excruciating hours later and I finally ambled over the threshold into the night’s accommodation. Subra, a friend of a decade and a half, who had graciously let me crash at his place was now definitely having second thoughts after seeing me in a pile on his living room floor. My mind was a mess and my body was broken. That night, I made a promise to myself that I wouldn’t continue in the morning.

***

Day 3

The next day, I woke up at 11 AM, a whole three hours after I was scheduled to leave. Groggy, weak, and in pain, every step from the bed to the living room was a conscious and deliberate effort. My legs were swollen and the bottom of my feet were tender. After filling up on coffee and a thosai breakfast Subra prepared with unexpected skill, I knew I had to make a decision. If I was going to finish the walk, I would finish it on my terms.

I emptied my entire bag of all its contents and only put back the essentials. Finally, at 1 PM, I set off. The usual pain and discomfort showed itself but they didn’t have as immense a hold on me.

It seemed that sometime during the night, my mind had formed a husky exterior, now more focused on the goal, and more impervious to thoughts of giving up.

A phrase from an ultrarunning friend materialised in my head: “form calluses in your mind.” I was no longer as thin-skinned as I was when I started, I knew that for sure.

About 10km in on Day 3, I was joined by an old acquaintance, Sonya, who had decided that she was going to enlist in the march pretty offhandedly. How casually people throw themselves in the path of pain, I will never understand. Then again, I was walking 150km around an island completely voluntarily, so maybe I did understand.

I want to say the day breezed by, but it didn’t; even losing myself in conversation with Sonya offered little respite. What helped was the knowledge that it was no longer a question of if I would finish the walk, but when. Thus, the last half of the journey consisted of watching the clock, knowing that if I just kept one foot in front of the other, time would eventually carry me to the finish line.

Approaching the last 10km, we were joined by friends Han and Jovan who followed Sonya’s lead and threw themselves in the line of fire.

We were walking roadkill, resembling something more from the Night Of The Living Dead than Rocky. But make no mistake, beneath the surface of those jangly, rattling bags of meat and bone, the opening riff of “Eye Of The Tiger” was pumping hard in our chests. We were going to finish strong.

Three kilometres shy of the finish line, a searing pain shot out from my right heel and seized my leg. From a canter to a trot, I dropped to a full stop as the slightest bit of weight on my right heel caused a roar of pain that demanded attention. I dropped to the floor, Jovan crouched to my side, and as I described the pain, the words “stress fracture” and “muscle tear” drifted in and out of earshot. ‘Tis but a scratch I thought to myself.

After an excruciating 10 minutes of swivels, tilts, and rubs, my foot allowed about half my body weight on it. The result was an exaggerated limp that looked a lot more concerning than it was. Gratefully, Han and Jovan, ceased discussions on how to carry me to the finish line. I was on the last 3km, and I’d be damned if I let something as frivolous as a possible life altering injury stop me from finishing.

If the last 10km was euphoria, then the last 1km was unadulterated joy.

I had walked the length of an ultramarathon — nearly 160km — with next to no training. What a mindbogglingly dumb thing to do. But I did it, and around Singapore no less. Upon seeing the finish line, I slowed my pace and tried to take everything in as best as I could.

The jetty pushed out towards a wide channel in between Singapore and Malaysia. Once clear of the trees and out onto the elevated walkway, the sea breeze immediately hit me, strong enough that I had to lean into it. Along the jetty, there were people with fishing lines cast far into the black water, teenagers doing wheelies on fixies, and couples revelling in romantic anonymity.

It was 9 PM when I placed both hands on the wooden railing at the end of the jetty, back where I started. It felt weird to stop walking without feeling an urgent push to keep moving.

Before the walk, I had never really subjected myself to putting my body, mind, and belief system on the line for the sake of indulging my own curiosities. Taking such grand departures out of my comfort zone, and experiencing lengths of sustained unpleasantness led to lessons that I knew in theory, but never in practice.

Water became a precious commodity, a park bench was a source of great comfort, and more than usual, friends became pillars of strength and indispensable resources of knowledge and motivation.

The Long Walk taught me to feel overwhelming appreciation for things that I usually take for granted. It taught me that I was tougher than I made myself out to be and that I was capable of so much more than I gave myself credit for.

Looking back at the days before the walk, I was filled with fear and doubt, aware that a million things could go south in a second, and in a way they did. But it also showed me that just because things are difficult, doesn’t mean they aren’t worth it or shouldn’t be done. It only means that the end is going to be so much sweeter. I’m trying my best to take that same attitude with the coronavirus lockdown.

I think I did it because I could, because it was out there, and because once I thought about it, I couldn’t stop thinking about it. I’ll remember those three days for the rest of my life. If I had stayed in the office, those days would have been as inconsequential and as undefined as the next three. So maybe I’m asking the wrong question. Maybe instead of asking why I did it, I should be asking, why not?

Find Aditya on Instagram.

More

From VICE

-

In Good Taste -

Screenshot: tinyBuild -

Ru Callender leads a procession through the streets of Liverpool for the KLF's annual Toxteth Day of the Dead celebration. Photo by Thomas Ecke -

Collage by VICE