“Is photography art?” Almost 200 years from the advent of the medium, critics are still lashing out at each other over this tenacious question. First posed in the early 19th century by the Pictorialists, the debate over the legitimacy of photography as a form of fine art will endure as long as the medium itself exists and its tools—and thereby its products—continue to change with shifts in technology. With Instagram unleashing over 40 million photos a day, Snapchat’s 400 million daily snaps, and digital photography’s general proliferation of the medium, the question becomes not only whether or not photography is art, but can anyone do it?

The Pictorialism movement began in 1902, almost 15 years after Kodak released the first “snapshot” camera and defined photography as a tool for documentation. Fueled by the spawn of the “instant” photograph, Alfred Stieglitz, an American photographer who spent his life championing photography as an artform, gathered a group of other likeminded photographers. In a nod to the British photography group, the Secessionists, they formed an American counterpart, the Photo-Secession, challenging society to view photography as a medium as creatively expressive as that of painting.

Videos by VICE

Collection of National Media Museum/Kodak Museum via

Pictorialist photography was known for its otherworldly aesthetic. Its artistic approach to the photographic image was the first of its kind, placing emphasis on composition, color, and the photographer’s craft. Many Pictorialists used alternative processes, such as gum bichromate—a printing process that involves multiple layers of light sensitive chemicals on watercolor or printmaking paper, yielding a painterly quality to the image—to develop their photographs, in response to the standardized route of printing that photography had taken with Kodak’s burgeoning empire. The work of Pictorialist photographers such as Edward Steichen, Clarence White, and Alfred Stieglitz set the stage for photography to be viewed through a fine art lens and paved the way for astronomical sales over a century later.

The Ring Toss, 1899, Clarence H. White (American, 1871–1925) Gum bichromate print; 7 1/16 x 5 1/2 in. (18 x 13.9 cm) Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1933 (33.43.303) via

But in the last 100 years, photography has transitioned yet again from the aesthetic put forth by the Pictorialists. Not only has it experienced growth and change as any art form does, from the impressionistic imagery of Stieglitz’s early work, to the realism of Walker Evans, to the witty, absurdist candids of Elliott Erwitt, but the medium itself has undergone a significant shift in the way its product is produced.

With widespread technological innovations, photography has become arguably the most ubiquitous artistic medium—produced en masse at an unprecedented rate. We find ourselves faced, yet again, with the well-worn question of artistic validity in mass production. Stieglitz might argue that 21st century photography has become diluted by its proliferation, and he would have a point. But does the prevalence of photography actually detract from its artistic integrity?

The Flatiron, 1904 Edward J. Steichen (American, born Luxembourg, 1879–1973) Gum bichromate over platinum print via

Photography critic Sean O’Hagan claims that it does not. In his brilliant rebuttal to his colleague’s notion that photography is not art, he states, “Photography is as vibrant as it has ever been—more so in response to the digital world, which Jonathan mistakenly thinks has made everyone a great photographer. It hasn’t. It has made it easy for people to take—and disseminate—photographs, that’s all. A great photographer can make a great photograph whatever the camera. A bad one will still make a bad photograph on a two grand digital camera that does everything for you. It’s about a way of seeing, not technology.”

Though there are contemporary photographers that fall into a category loosely termed Neo-Pictorialism, the emphasis is on the aesthetic with none of the activist bent so integral to the Photo-Secession. A century after the fight for legitimacy, photography is now cycling back to its beginnings with a rise in traditional and alternative processes through companies such as the Impossible Project and Lomography seeking to reclaim analog photography and leave behind the freneticism and immediate gratification of a digital photograph—much in the same way that Pictorialists sought to slow down the photography of their time with an eye to the myriad possibilities of the medium.

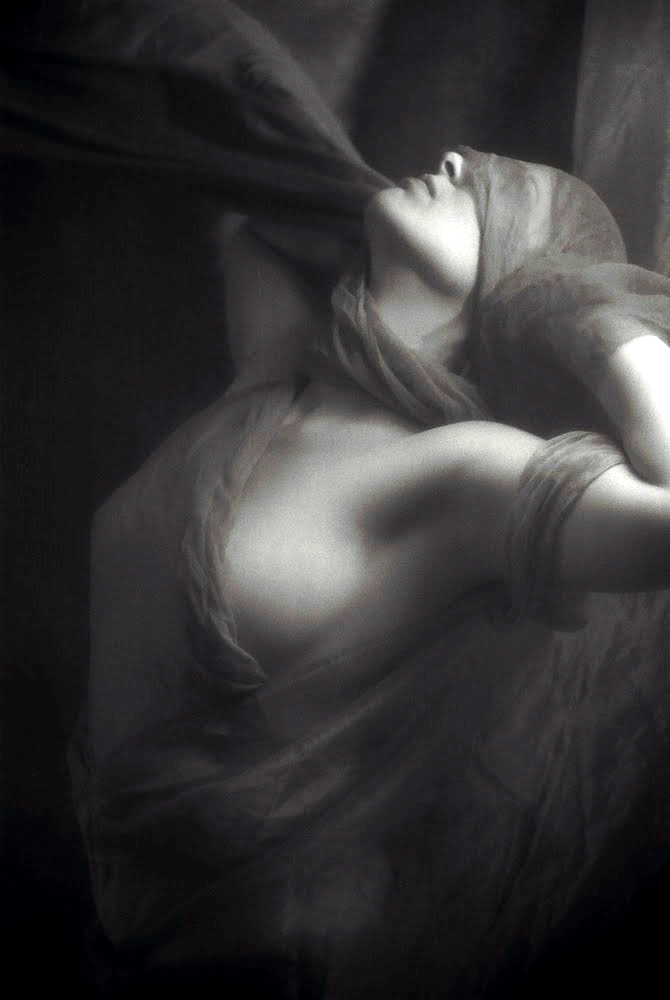

© Francis A. Willey via

Click here to learn more about Pictorialism.

Related:

Original Creators: The New Vision Of László Moholy-Nagy