Take the London Underground, and it’s more than likely you’ll see an advert for Jack Daniel’s.

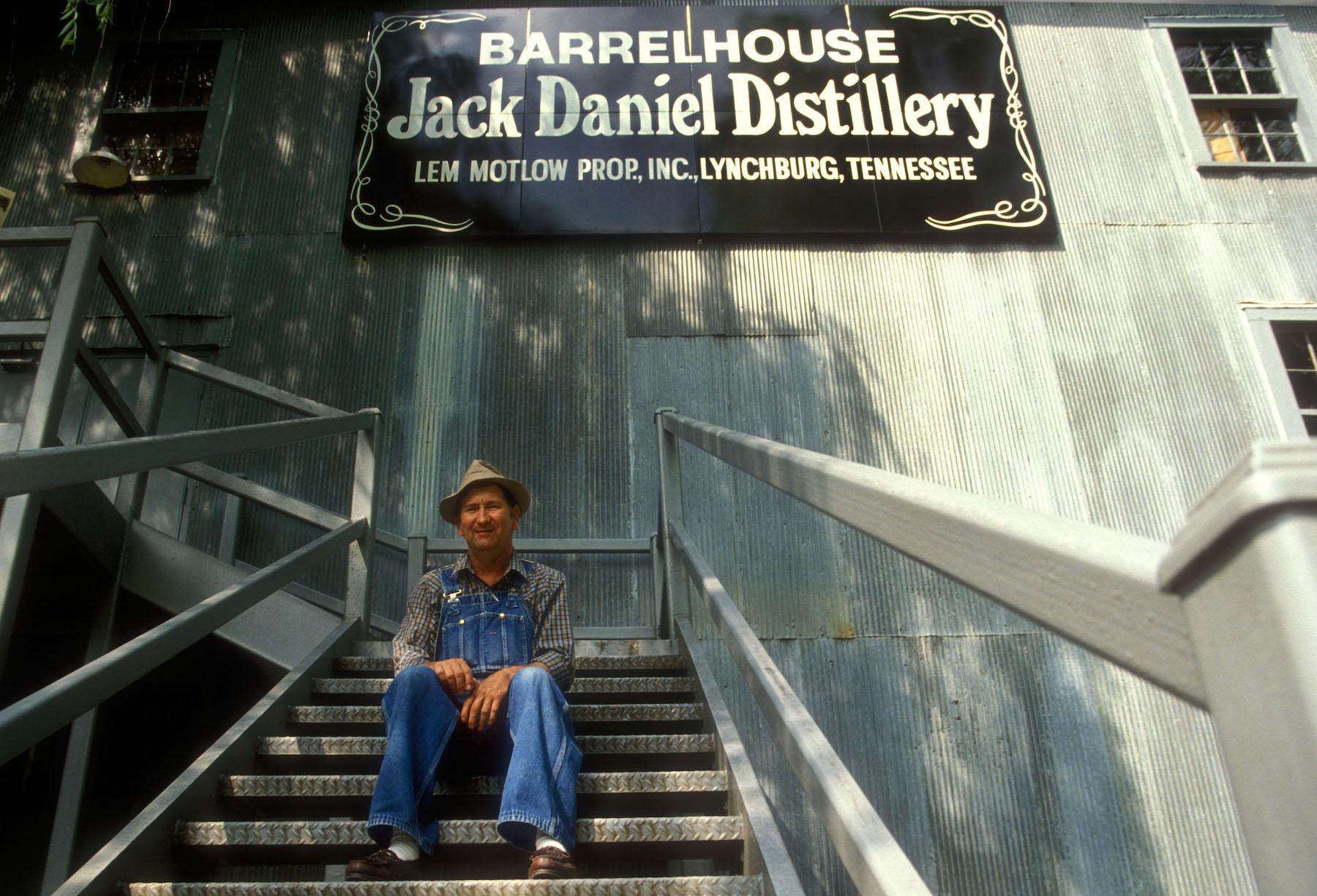

Waiting on a platform, you will look up to see a poster sporting a black-and-white photo accompanied by some text about the real-life Mr Jack Daniel and the folks down in the little old town of Lynchburg, Tennessee, where the whiskey is made.

Videos by VICE

You might learn that “Mr Jack” was a game but unsophisticated musician, that he was a lifelong bachelor who was nevertheless a hit with the ladies, or that he only loved one woman – but that it was a case of unrequited love. You might learn that there’s only one stop sign in Lynchburg, and that the town is in a dry county, meaning you can’t legally buy the world’s best-selling American whiskey where it’s made. You may also learn that the only thing that “stirs up the local ducks” is a “squeaky grain wagon”.

If you are not you, but are in fact me, then you will become curiously obsessed with where these adverts come from, what they mean and whether there is any truth in them at all. You will think about the disparity between ageing pickup artists ordering JD and Coke in mirror-lined bars and monochrome posters of old white dudes rolling barrels around in their dungarees.

You will affect an unconvincing southern accent and mutter things like, “Old Mr Jack wasn’t much for reading, but he could sure as hell comprehend a glass of whiskey,” or: “We got a saying down here in Lynchburg: a goose in the barrel is worth twice a frog in the tree.”

Depending on who you believe, Jasper “Jack” Daniel was born in either 1849 or 1850. The youngest of ten children, he never grew any higher than five feet and an inch, and by the time he was a teenager both his mother and father were dead.

Parcelled off to a local preacher and moonshine maker, Jack learned the tricks of the distilling trade from a slave called Nathan “Nearest” Green, a fact only recently recognised by Brown-Forman, the multi-billion dollar corporation that owns the Jack Daniel’s Distillery.

In the mid-1950s, Jack Daniel’s launched its “Postcards from Lynchburg” advertising campaign, which ran for four decades in American print publications. This campaign is still alive: it runs on the London Underground, and nowhere else.

Before the folksy whimsy of “Postcards from Lynchburg”, Jack Daniel’s was marketed as a luxury product. Newspaper and magazine adverts from the early 1950s show gentlemen in dinner jackets and lounge suits raising glasses of Jack under the strap-line, “Man to man, the good word gets around.” In one, a black waiter in a white uniform holds a tray of Jack Daniel’s aloft as a group of white fellows sit around, no doubt discussing that fine Jack they’re all sipping.

In other adverts of this era, JD was described straightforwardly as a “luxury in rare whiskies”, the “choice of men who want only the best”, “the rarest whiskey in the world” and “worth the difference in cost”.

“Jack Daniel’s is, frankly, EXPENSIVE!” announced another, exclamation mark, capital letters and all.

According to Phil Epps, Jack Daniel’s global brand director, the luxury product strategy changed after articles in Fortune and Time magazines paid attention to the unusual, close-knit way in which Jack Daniel’s was made, in this little old distillery in the Tennessee hills.

Speaking to me as he’s driving back from the distillery to Louisville, Kentucky, where he’s lived for almost ten years, Epps’ accent is unmistakably English. He’s from Winchester and has just switched off a football (soccer) podcast. His kids speak in Kentucky accents and he’s one of the main people in charge of selling a whiskey from the American south.

Epps tells me that in the American 1950s, at a time when more and more people were moving to the suburbs and the cities, the articles focusing on the Jack Daniel’s distillery talked about “this small brand that was starting to get some interest, and these men’s men who were making the whiskey”.

“We’re not selling a bottle of booze,” the original creative director of “Postcards from Lynchburg” said. “We’re selling a place.” A new style and technique was adopted – one that, says Epps, was an “antidote to the time”.

Americans may, in increasing numbers, have been putting on white shirts and going to work in offices, living in suburbs and riding the commuter train, but they still longed for the great outdoors, for community, for something they could believe was authentic.

Increasingly bourgeois, they were drawn to the anti-bourgeois. They wanted to purchase it. All adverts tell a story – even if the story is just that you have a headache, and if you take this pill you won’t have a headache – and here was the right story at the right time, a tale about a down-home place where people worked in blue-collared overalls, told to consumers in cities where people worked in white collars. As Epps says: “We’re a storytelling brand built on authenticity and heritage.”

Jack Daniel began his distillery in 1875, but it was in the 1950s, with the formulation of the advertising strategy you see on the Tube, that this distillery – the place it’s in and the people who work there – got spun into a tradition.

This kind of heritage branding – as the Invention of Tradition, a 1983 book edited by Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger, demonstrated – is nothing new. From the highlands of Scotland, where supposedly “ancient” clan tartans were fabricated in the 19th century, to European colonies across the world, traditions were invented in order, among other things, to legitimise control and promote a sense of unity. Or, in a modern context: brand loyalty.

“Traditions which appear or claim to be old are often quite recent in origin and sometimes invented,” Hobsbawm writes in the book’s introduction.

On the Tube, Jack Daniel’s has a captive audience ready to receive its tradition. It takes about the same amount of time to read a Jack Daniel’s advert as it does for your train to come. The posters’ dark colours won’t take too much of a beating from the grubby environment they exist in.

As the creative strategist William Skeaping puts it: “The design is legible from the platform, the ol’ timer fonts don’t feel menacingly trendy first thing in the morning, and you could probably look at them with a hangover and not have flashbacks.”

“Honestly, this is the best stuff we do,” says Phil Epps, of the Underground adverts. He adds that Jack Daniel’s gets an “incredible deal” – JD’s annual package would cost “any old punter walking in off the street” £1 million a year. As it is, they get it for far less.

Epps says his team talk about the “tensions” present in marketing Jack Daniel’s, particularly between the “old white dudes” making the drink and the more rock ‘n’ roll reputation the brand tries to cultivate elsewhere (Slash loves his Jack, the Jack Daniel’s logo is forever popping up at festivals).

Other tensions not mentioned by Epps would include the disparity between the folksy tradition presented in the adverts, and bar bros ordering JD-and-Coke partly because of the rock ‘n’ roll thing, and partly because it just rolls off the tongue and they don’t know what else to order.

Then there’s the tension between truth and mythology. Mr Jack of the adverts is in love with a woman called Clara, who doesn’t love him back. Peter Krass, Jack’s biographer, told me the girl he was in love with was actually called Fannie Blythe, and, in a strictly Baptist part of the country, Fannie’s family would not let her marry Jack because “he was a sinner who make liquor”.

Then there are darker stories; stories that get left out. Lem Motlow, Jack Daniel’s nephew, was a key part of the business side of the distillery before, during and after the prohibition period. He was also, by many accounts, a murderer and a racist. In 1924, drunk and on a train, he shot a black porter. The man died, but Motlow, deploying seven lawyers, mounted a racist defence that played heavily on the prejudices of the jurors. Motlow got off, with the head juror saying, “We didn’t believe the negro.”

Such horror is hardly surprising, and – again, unsurprisingly, will always be kept away from the brand story, where possible. In Lynchburg, and in the people who work there, Jack Daniel’s have something to draw on. The town really is, Peter Krass told me, “This place deep in the countryside, with folks like those depicted in some of the ads.”

That reality is then cooked up into something that, standing on a Tube platform, can seem almost like a parody of a time and place.

Lora Faris, a copywriter who worked on the Tube adverts between 2015 and 2017, told me that her boss said she should imagine an “old Southern lawyer, like Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird“, when she was writing. There is a “Wizard of Oz, Emerald City” feeling to the way Lynchburg is portrayed, she said.

Having already worked on a number of the adverts, Faris – who is from Ohio – actually visited Tennessee. “‘Wait, this is a real thing,’” she remembers thinking after arriving in Lynchburg. “I was blown away by how ‘authentic’ it was.”

This longing for authenticity is almost pathological. It is experienced as a form of melancholy, an attachment to something we have probably never known and that may not have existed. Global capitalism unmoors us from place and time and community, and then, feeding on that sense of dislocation, tries to sell those things back to us.

Brown-Forman, which owns Jack Daniel’s, is a multi-national conglomerate that makes hundreds of millions of dollars in profit every year. But the Jack Daniel’s distillery is in a little old town in Lynchburg, Tennessee. Down there, it’s just the ducks, the grain wagons and a few old boys rolling some barrels about. Folks just ain’t in no kind of hurry.

If that’s a cliché, then here’s another one: on the London Underground, there is nothing but hurry. Alienated commuters wait for deliverance. On the platform, they look up and there’s old Mr Jack, a glint in his eye and a goose in his back pocket. There are the rolling hills of Tennessee, the winding lanes and the shady hollows. Stretch out your hand, you can almost touch it.