It’s 7:06AM and I’m staring at my first CCTV camera of the day – the opening scene of the spectacularly dull multi-camera short film that is my daily walk to work.

When I say “multi-camera” I mean 90 cameras. Ninety CCTV lenses capturing every step of the 42-minute journey from my flat to the office, or roughly one every two minutes. I know how many cameras record my commute because I counted and logged the location of each one of them, to find out what happens to my image once it’s been captured and whether I have any control over it.

Videos by VICE

In theory, this should have been simple enough. According to the Information Commissioner’s Office, most uses of CCTV are covered by the Data Protection Act (DPA), meaning you have the right to view images collected of you – if, that is, you have the time and patience to explain the DPA to all the people who operate those CCTV cameras. Which, depressingly, I did.

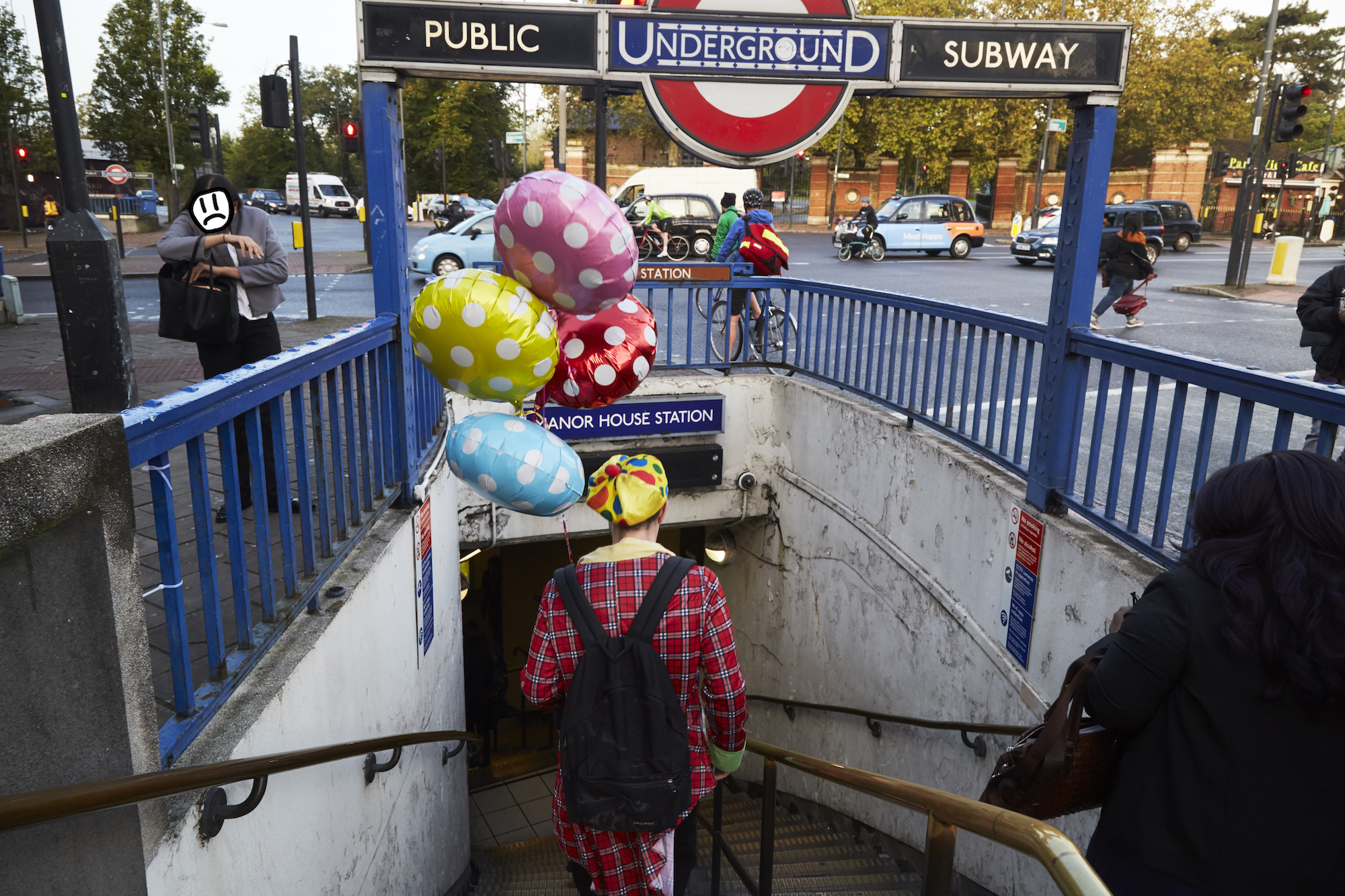

Aware that I needed to wear something conspicuous so the people scanning through footage for me would know who I was, I dressed like a clown. This didn’t go down particularly well on the rammed Northern Line (carriage 51724), maybe because of the four helium balloons I was carrying, but also maybe because people assumed I was a YouTuber doing a social experiment and, understandably, wanted absolutely nothing to do with me.

The walk from the tube to the office takes around seven minutes. I saw 25 cameras on that route, so roughly one every 17 seconds. For obvious reasons, I don’t want to sound too PrisonPlanet here – London is famously one of the most surveilled cities in the world, with 68 cameras for every 1,000 people – but that does seem a little excessive. It also explains with the UK CCTV industry is worth an estimated £2.35 billion.

Once I’d completed my journey I found contact details for nearly every building a camera was attached to and emailed to explain I was “requesting information held about me under the DPA”, described myself (“wearing a clown outfit and carrying balloons on a string”) and gave the exact time, date and location I was captured. I requested that they provide me with a copy of the CCTV image and then delete it. For the 14 buildings I couldn’t find an email address for, I hand-delivered letters outlining my request.

Turns out people don’t like being asked to rifle through hours of CCTV footage so a guy dressed as a clown can write an article about it.

Most respondents just didn’t get back to me, but of those who did: some asked for a copy of my ID, some asked for a reference picture of me on the day, some said they had already deleted the footage as too much time had lapsed, some said it was illegal to provide me with the data, some said I could come to their offices to view it, some said I must go to their offices and show ID. One said they would give me the data, but only if I was “in a position to tender the work out for the editing of the video on our premises through a reputable contractor at your own cost”.

I was caught on cameras operated by various local councils. One said they could only provide the data to the police if an incident had taken place, or to a solicitor working on my behalf at a cost of “£33 footage search fee or £132 for footage release fee”. Nobody entertained the idea of erasing the data for me completely.

I ended up with a handful of video recordings and some screengrabs – some of which breached other people’s data privacy, while others were apparently very worried about breaching my own privacy, to me, so pixellated my face out.

It would seem that while a ton of different entities – private, commercial and public – collect and store our data, few know how to handle it properly, or understand the legal implications of their actions. In most cases – in my experience, at least – that means you won’t be able to access your data as you legally should be able to.

Ioannis Kouvakas, Legal Officer at the human rights charity Privacy International, explained why that’s a problem: “Capturing images through CCTV cameras not only triggers privacy protections but also data protections. This means that, under data protection laws, individuals are entitled to certain rights. For instance, [among many others] they have the right to request access to their data and be provided with an exact copy. Or the right to rectify their data or have it erased.”

Those rules apply once your image has been captured – but what about before?

“There are transparency requirements: individuals must be given adequate notice before, so that they’re aware of what’s happening,” Kouvakas explained. Again, this wasn’t the case for me. At a handful of locations there were signs alerting passersby to the fact there was a CCTV camera there, and how to get in touch, but by the time I was close enough to read them I’d already been filmed. So in that respect, every single collection of my data was unlawful.

“The sign needs to exist before your image is captured, otherwise there’s no point in starting to film me, then telling me there’s CCTV in place,” said Kouvakas. “It’s based on consent.”

Was he surprised that I struggled to flex my legal rights after being filmed? “It doesn’t surprise me, no, because we’re running similar projects, filing a series of complaints against data procurers – online stuff, mainly – and the difficulties are immense,” he said. “You wouldn’t believe what companies can come up with. First, endless back-and-forth emails. Second, some companies said: ‘Just sign this document and we’ll give you the data.’ After taking a look at the document it was actually an erasure request! Then they say, ‘We just deleted it – you asked for us to delete it.’”

“There’s an enormous amount of surveillance in the UK,” said Hannah Couchman, a Policy Campaign Officer the human rights charity Liberty, who specialises in human rights and technology. “There are different methods of surveillance that can be deployed against either particular individuals or entire communities. It is, of course, being developed into facial recognition technology with the use of things like IMSI [International Mobile Subscriber Identity] catchers and cell phone extractions [allowing authorities to hack your phone to, say, find out if you were at a specific protest].”

If that already sounds worryingly like Minority Report, it gets worse: “We know that existing CCTV networks can be retrofitted with not only things like facial recognition,” said Couchman, “but also what they term ‘smart technology’, which allows the camera in theory to make predictions about how people are behaving. We’re seeing an expanding web of surveillance that we’re all caught in on a daily basis as we just try and go about our daily lives.”

Big Surveillance would argue that CCTV either deters crime or helps police to catch offenders, and it’s hard to disagree. But there surely comes a point at which authorities and private companies are overstepping the mark – and as far as Hannah Couchman is concerned, we’re already hurtling ever faster towards an insidious creep of invasive surveillance: “We know, for example, in Glasgow they are looking at CCTV cameras which aren’t facial recognition-enabled, but they have what they call ‘Suspect Search’, where they can essentially scan things like the texture of your clothing and use that to track and monitor you.”

She continued: “We already have things like workplace surveillance coming in. Your average person might get up in the morning and their Alexa assistant is immediately taking data about what time they woke up and whether or not they brushed their teeth, what route they are taking to work and where their meetings are today. Then they open their laptop on the train, which collects data; they’re on the train’s CCTV; then their workplace monitoring kicks in, and so on and so on.”

Granted, some people simply don’t care that their commute is being recorded, but expanded surveillance has bigger implications than that: the misuse of data, a decreased expectation of privacy, governments using information for their own ends and innocent people being accused of crimes they didn’t commit.

Couchman doesn’t believe the worst scenarios are inevitable, but does say that resisting them would require a movement. “We have to have agreement with people that this is the direction that we don’t want to go in,” she explained. “Part of that is thinking about the inevitable dystopian scenario where, in theory, we could have cameras monitoring us 24/7.”

The Information Commissioner’s Office had nobody available to comment.

More

From VICE

-

Photo by Lucas Coly / Facebook -

Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images -

A sniffer dog checks bags in England, UK. Photo by Maureen McLean/Shutterstock -

Image Credit: Natalli Amato