Today, sex toys are hardly anything to bat an eye at. Today, they have their own expos, write-ups in the New York Times, and novelty lines inspired by TV shows. But we weren’t always such a vibrator-happy society. In her forthcoming book, “Buzz: A Stimulating History Of The Sex Toy,” historian Hallie Lieberman sets about reconciling America’s complex cultural past surrounding sex toys.

“Sex toys absorb any meaning that’s around them,” she told Broadly. “They’ve meant so many different things to people: devices that can further conservative values of monogamy and heterosexual marriage, further radical gay sex and gay rights, and transform disabled people’s lives.”

Videos by VICE

“Buzz” is exhaustively researched and formed on the basis of 20 interviews, 27 archival collections, and 825 footnotes. All told, Lieberman traveled approximately 12,647 miles to tell this story fully. If you count the years she spent illegally selling sex toys in tupperware-style parties as research, she has been working on her upcoming book for over a decade. As a feminist, she’s devoted her life’s work to understanding how devices that bring many women pleasure have historically been shrouded in legislation, stigma, and secrecy.

Perhaps the most surprising part of Lieberman’s account is how it differs from scholar Rachel Maines’ groundbreaking work from 1998, “The Technology of Orgasm: ‘Hysteria,’ the Vibrator, and Women’s Satisfaction.” This being the narrative that vibrators were introduced by Victorian doctors who would regularly and routinely masturbate patients with vibrators as a means of treating hysteria. (Lieberman is not the first to counter Maine’s writings.)

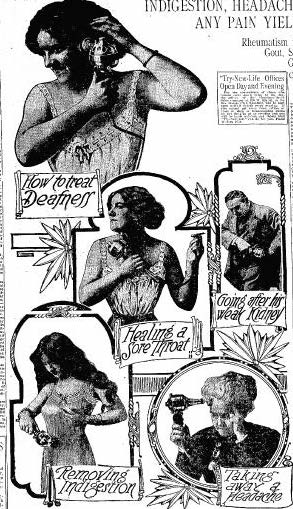

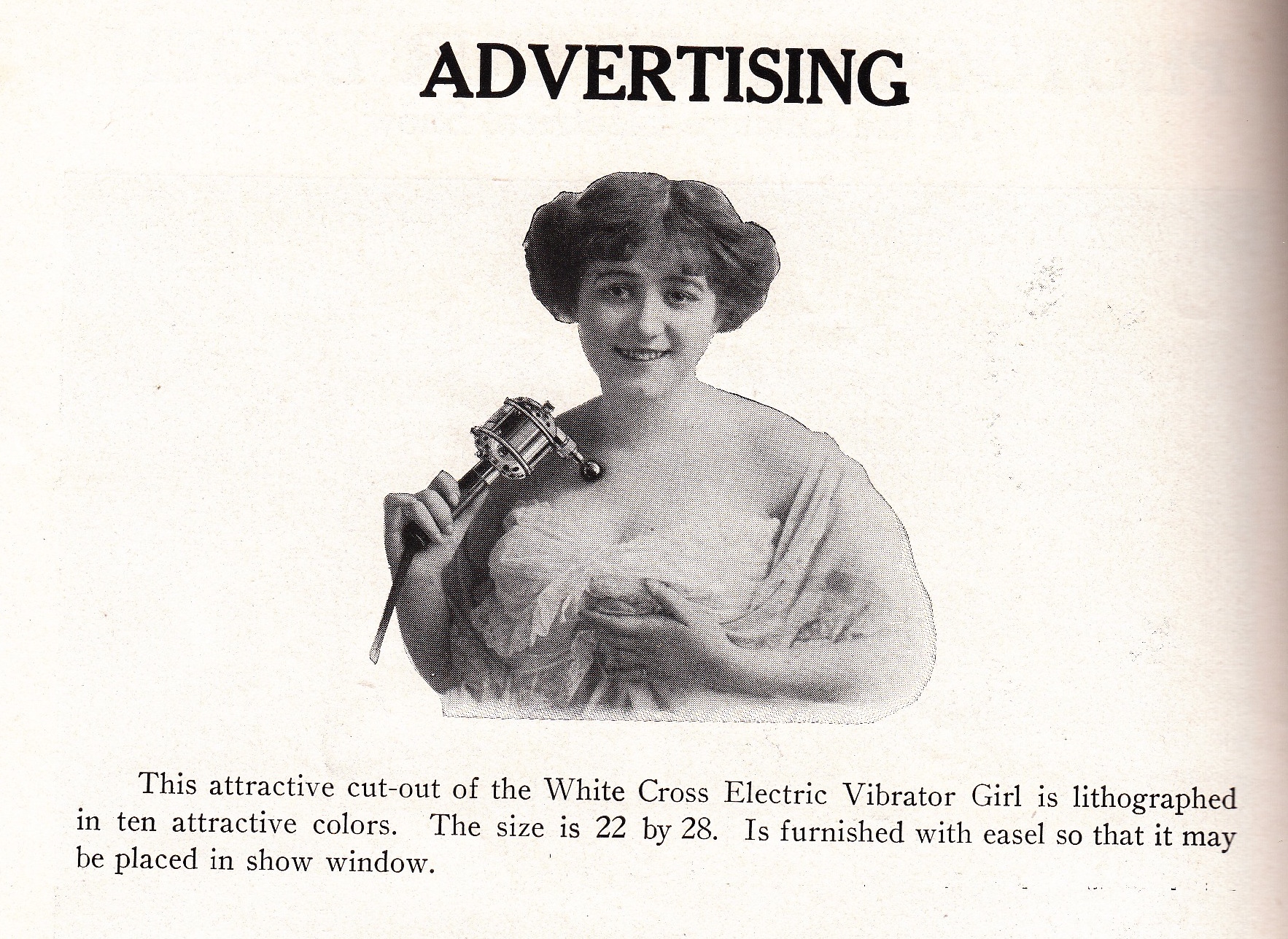

“I have found in the American Medical Association women complaining about doctors trying to do immoral things like touch their genitals, and men too being vibrated in sexual ways,” she acknowledges. “But as far as the regular medical profession, no, people didn’t do that. The reality is that hysteria was one of like 300 ailments that vibrators were sold for and it wasn’t really doctors using them. It was consumers buying them.”

Rather focus on this time period, Lieberman highlights the feminist sex toy store boom of the 1970s that revolutionized the way women’s sexuality was seen. She also dives into the simultaneously occurring operations of the mainstream sex toy industry, which was international at scale, largely male-dominated and sometimes criminal. The way sex toys were sold, she writes, was hugely telling of the cultural and gender norms of the time.

Speaking with Broadly, Lieberman discussed how these sex-positive feminists fought to reclaim the sex toy and provide future generations of women with autonomy, sex positivity, and pleasure. It wasn’t an easy task, and they were often met with opposition even within their own peer groups. In her view, we’ve taken the men and women we have to thank for the little buddies in the bedside drawer for granted, and it’s time they get their due.

Broadly: Why were sex toys like dildos considered obscene unless they were disguised as novelties or marketed specifically as medical devices to assist in penetration during heterosexual sex for such a long time? [Note: Prior to 1962, it was a felony to engage in “sodomy” in every state.]

Lieberman: It reflected the gender roles of the time. [The industry] was really more focused on the heterosexual norm of man penetrating woman, even after research came out showing women have more pleasure from clitoral stimulation and only about one-third of women get orgasms from intercourse.

Sex toys [positioned as being] for couples had always been more socially acceptable because they don’t mess up the status quo. The idea of a sexually independent woman masturbating and not needing a man was seen as threatening. [This way] the woman’s not getting it unless the man is controlling the toy. Or at least that’s the lie they told in the ads.

Which is why some of the earliest mass-produced American dildos were actually strap-ons, right? You write that they were sold as a “marital aids” for men to penetrate their wives if they couldn’t perform without assistance, rather than devices intended for a woman’s solo use.

Yeah, now we tend to think of strap-on dildos as pegging for heterosexuals or lesbian and bisexual women using them in their relationships. No one thinks of it this way, but your dad might’ve worn a strap-on dildo!

Prior to the rise of feminist sex stores in the 1970s [e.g. The Pleasure Chest , and Eve’s Garden in NYC and Good Vibrations in San Francisco], what were your options if you were a woman looking to buy a sex toy?

You had to go to one of these seedy stores on the outskirts of town because of zoning regulations. Most had jack-off booths in the back that were playing little porn movies, so there are men actually masturbating, and you’d be the only woman in there. It was creepy!

Another way to get sex toys was through mail order but sending sexual things through the mail could be illegal if they were considered obscene, so that was hard too. If they wanted a vibrator they could go to Macy’s to buy a vibrator that was marketed for other purposes as an appliance. But there was shame in that too. Dell Williams [founder of what’s considered the first woman-owned feminist sex toy shop, Eve’s Garden] was inspired to sell vibrators after she went to Macy’s for one and a sales clerk [acted judgmental].

How were these new feminist store options different?

Women felt safe and comfortable. At the Pleasure Chest [the first feminist sex toy store, in Lieberman’s view, which was run by two gay men named Duane Colglazier and Bill Rifkin in New York City], catalogues noted the importance of the clitoris. That was kind of revolutionary of sex toy marketing at the time. It was also a boutique that started as a mattress store. They didn’t black out the windows.

Dell Williams only allowed women into Eve’s Garden at first, so this was the antithesis of the male-focused sex toy stores at the time. And she didn’t sell dildos in the beginning; she only sold three items and they were all clitorally-focused. Although stores like these didn’t have a lot of outlets, their cultural influence was profound.

You also write about how the larger women’s movement was torn over this emerging pro-masturbation, sex-positive feminist ethos.

Right, there wasn’t a unified view about whether sex toys were good or bad. There was infighting, there were arguments over whether a commodity could be liberating, whether lesbians should use dildos, whether straight people should [use dildos], whether you should use anything to interfere with the naturalness of sex…there was all sorts of disagreement. During the time of second wave feminism there was this split between people who thought change should happen on an individual level in the bedroom versus those who thought change should happen in the boardroom. Then there was this idea that masturbation was selfish and antisocial, like, “Why the hell would you focus on a solitary sexual activity when we’re trying to build a community?” I realized there’s been this big fight to get to where we are today where most feminists see sex toys are seen as symbols of women taking control of their sexuality, or being liberated.

What do you think of where we are today when it comes to our views on sex and sex toys?

I think sexual pleasure is still not as important in feminism as it should be.

In America, we’re always more comfortable talking about sex in a negative way, talking about sexual violence or trafficking or assault—and there is so much needs to be improved, we need to be talking about this—but we also need to be having these conversations about sexual pleasure.

Not enough attention is given to the orgasm gap. And that’s because there is more of a backlash when you talk about sexual pleasure, especially in academia. You can get grants to study sexual assault, you can get grants to study STDs, but getting grants to study sexual pleasure is still very, very challenging.

It’s a shame that sexual pleasure isn’t taken as seriously. Orgasm should be seen as a right. Like healthcare is a human right, orgasm is a human right. More women need to be having orgasms because nearly all men are.

More

From VICE

-

Marilyn, an attorney and former professional dominatrix, poses for a photo with her sub who is fully encased in latex on the Vancouver Fetish Cruise. Photo by Paige Taylor White. -

-

-