A version of this article originally appeared on VICE Netherlands.

In May 2021, the whole world watched as the simmering 70-year conflict between Israel and Palestine descended into yet another explosion of violence. The crisis centred around Palestinian protests against the eviction of four families from their homes in occupied East Jerusalem, and was further inflamed by Israeli forces storming of Al-Aqsa mosque, the third holiest site in Islam. Over 256 Palestinians and 13 Israelis died in the following weeks of unrest.

Videos by VICE

Two years later, the international spotlight is back on the conflict, after the political and military organisation ruling Gaza, Hamas, launched an attack against Israel, precipitating a state of war. At the time of writing, 3,478 people have been killed in Gaza and around 1,400 people in Israel as a result of this latest conflict, but the death toll rises sharply each day.

Many have struggled to understand the motivations behind this sudden escalation of violence. But over the past few years, relations between Israel and Palestinian territories have rapidly deteriorated. Hamas named this recent attack “Operation Al-Aqsa flood” in reference to Israeli forces’ repeated raids of the symbolic mosque.

This year, the far-right coalition leading Israel also ramped up raids in the West Bank, and made plain their plans to annex large parts of the West Bank, an illegal act under international law. Although neighbouring countries have always put Palestine at the core of their diplomatic relations to Israel, these attitudes are slowly changing. In 2020, the UAE and Bahrain signed a series of agreements with Israel to normalise relationships, and it is thought that Saudi Arabia might be nearing a similar agreement.

In short, a number of Palestinians now believe the only way to maintain a foothold on their land and claim their right to self-determination is through armed conflict. Experts have long warned these sentiments might soon lead to a Third Intifada, but Hamas’s offensive seems to have come first.

It’s often hard for people to picture what the situation in occupied Palestinian territories is really like beyond images of air raids on Gaza. One of the aspects of Israeli occupation not often talked about in the media is how local communities are being slowly separated from their land by Israeli settlers.

The small town of Beita, population 15,000, located 13 kilometres south of the Palestinian city of Nablus, offers an example of this process of erasure. So far, the community has managed to defend their land, but the situation is becoming increasingly tense.

In May 2021, a caravan of Israeli settlers installed around 50 one-storey homes among the olive groves near Beita; groves that the local Palestinian population economically depend on. The settlement – which was named Evyatar – had not been previously approved by the Israeli government, and was the fourth attempt at building an outpost in the area. This time, the settlers stayed for over a month, and were protected and assisted by Israeli soldiers.

Beita’s inhabitants did not accept this land grab, as – if the settlement had become permanent – they would have been no longer able to access their olive groves. On top of the traditional Friday demonstrations held weekly across Palestine, they also organised daily and nightly protests, where people used lasers, burning tyres and loud noises to annoy the settlers.

Eventually, the Beita model yielded some results: In June, the settlers struck a deal with the Israeli government and left. But the agreement also stated that the area would be turned into a military base and a religious school, and left open the possibility that the settlers might return one day. The one-storey homes, now empty, are still standing.

This partial success came at a high price for the residents of Beita. The protests were brutally suppressed by Israeli troops, who killed nine people, including a prominent activist, and injured thousands. Over 150 residents also had their permits to work in Israel revoked, according to a statement given to B’Tselem, a Jerusalem-based human rights NGO, by the deputy council head of Beita.

In October 2021, the locals were finally able to return to their olive groves for the harvest. But the fight wasn’t over: In early February 2022, the Israeli judiciary effectively authorised the settlers’ return. In 2023, Beita and the surrounding area were raided by settlers and the Israeli army. In August, The Times of Israel reported on footage that appeared to show soldiers shooting an unarmed villager in the back of the head.

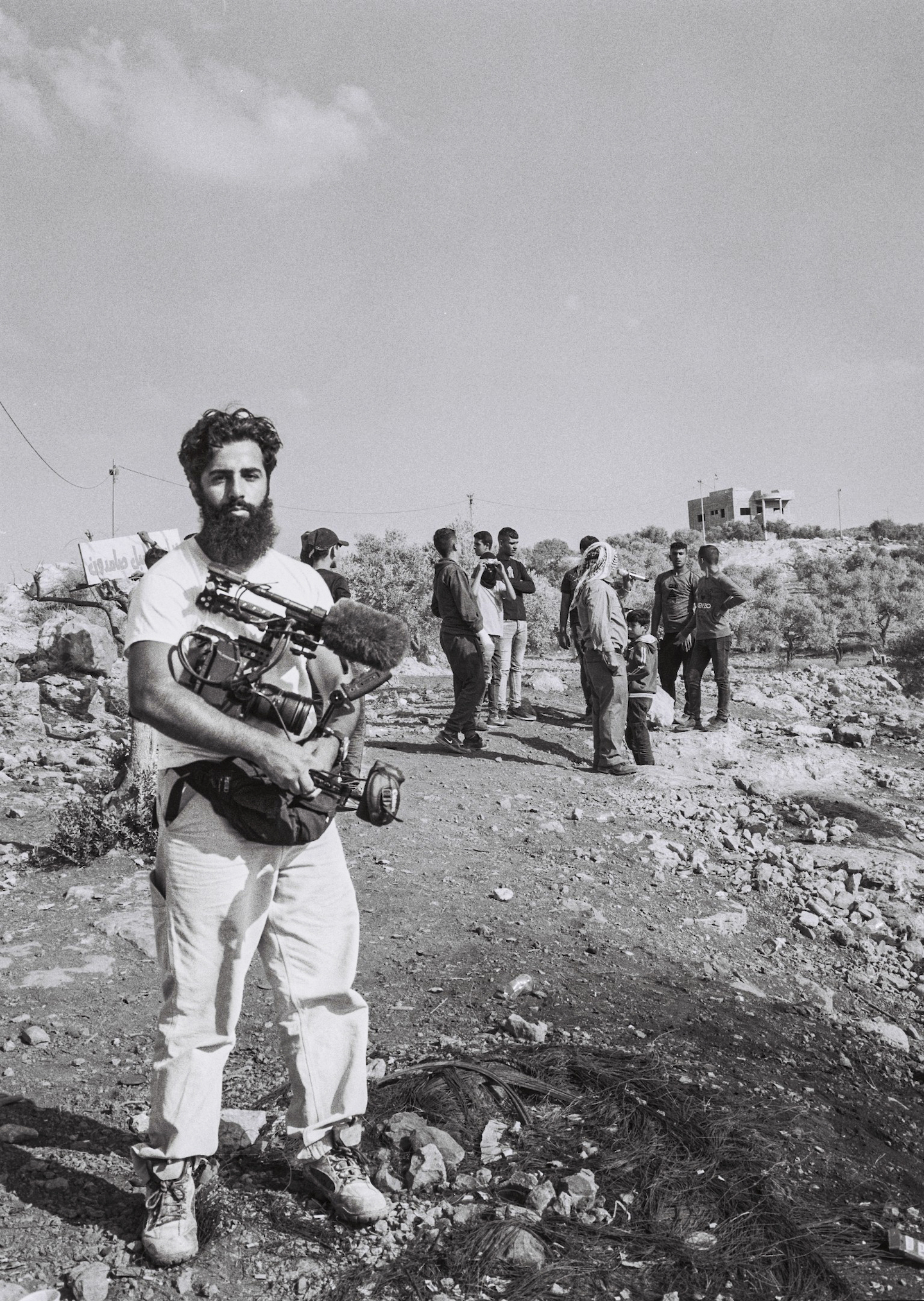

Sakir Khader is a Dutch-Palestinian documentary filmmaker with roots in Beita. His great-grandparents used to live there and he has relatives all over the area. Khader’s dad has lived in the Netherlands since he was a child, but they still travelled to Palestine every year to see family. Between June and November 2021, Khader made two trips to Beita to document life in this once sleepy town that was now a symbol of defiant resistance.

The resulting documentary, The Resistance of Beita – only available in Dutch – shows this contrast in opening scenes that portray the death of a young protester, which Khader witnessed last summer. “Moments before, I was sitting with him on a rock under a tree,” Khader tells VICE. “The first bullet missed me by a hair.”

Recounting the events of that day, Khader says he took shelter behind a water tank and heard another two shots after the first. “The third sounded very dull – bam, it went right through his head,” he says. “I knew who it was, but I wasn’t sure. There was a huge mob and everything was covered in blood. But then I heard it was really him… I stood there crying for a while; I was overcome with emotions. But then you pick yourself back up and keep filming.”

Despite growing up in the Netherlands, Khader is no stranger to Israeli military violence. “I was ten or 11-years-old when Kosay, my nephew and best friend, was shot,” he says. The incident happened in Nablus in April 2002 during the Second Intifada. “He went into the garden to look at the soldiers through a hole in the wall and got two bullets to his heart.” Kosay was 11-years-old.

After a few weeks of protests in the summer of 2021, Beita’s story made it onto international news. Perhaps the media was interested in the striking images of Palestinian civil disobedience, images that “we know” and that “have been around for decades,” Khader speculates. But he wanted to tell a different story. His film focuses on the idea of existence as resistance, but also on the village’s daily rhythms as they are punctuated by the annual olive harvest and disrupted by the arrival of the settlers.

What is happening in Beita is not an isolated case. Israeli settlements are civilian communities built on territories internationally recognised as Palestinian and currently occupied by Israeli troops. That’s why they are illegal under international law. Their number depends on how you define them, but according to B’Tselem, there are now around 280 of them populated by around 440,000 people in total. In 2023, the trend of expansion of Israeli settlements continued, with 6,300 new housing units built in the occupied West Bank, and 3,580 in East Jerusalem.

Common amongst the settlers is the belief that all of the area geographically known as Palestine belongs to Israeli Jews due to historical and religious reasons. Many of these communities, including Evyatar, were built without government authorisation. But the state still guarantees their security through the military and allows them to join the Israeli power grid and water lines, among other benefits.

Scattered throughout the West Bank, these settlements also serve multiple political purposes. For one, they legitimise Israeli military presence throughout Palestinian territory. They also make it virtually impossible to imagine a Palestinian state, as hundreds of thousands of Jewish Israelis would have to be forcibly removed from their de facto homes to make that happen. Finally, they keep existing Palestinian communities separated from one another, since the Israeli settlements and the roads that connect them can only be used by Israelis or foreigners.

The constant takeover of small patches of land by settlers is compounded by other state policies, which make life for Palestinians ever more fragile and fragmented. These include: designating Palestinian areas as natural reserves; denying local residents permits to build homes, wells, and hospitals as well as demolishing existing structures; and protecting settlers who routinely use violence against Palestinians while imprisoning those who protest.

That’s why some analysts have come to define Israel’s occupation of the West Bank as a form of settler colonialism. This year saw a sharp rise in settler violence, to the indifference of the Israeli government. According to figures reported to the U.N., over 1,100 Palestinians were removed from their lands in the past year alone. Relocating people against their will could qualify as forcible transfer, U.N. officials warned, which is a crime against humanity.

Meanwhile, Palestinians in Beita try to live life as normally as possible. The ambulance carrying the body of the protester Khader saw killed that day in June happened to cross paths with a wedding procession. “They didn’t honk and turned off the music, out of respect,” he says. “Those people demonstrate on a Friday, and then on Saturday they’re at a wedding. They bury someone on a Monday, then they mourn for three days and then someone else gets married. Every house has lost someone. It hurts so much, but it is the Palestinian reality.”

The situation shows no signs of improving, as both Israeli settlements and Palestinian villages continue to grow, while their shared space and resources remain the same.

Khader did not grow up in this reality, so the decision to portray Palestinian stories was complicated for him. He says he put it off for a while: He didn’t feel ready, nor did he want to be pigeonholed into only directing movies about the tragedies of his family’s homeland.

But, with time, he understood why he felt the urge to make these movies. “I cannot liberate Palestine, not with a thousand films, not with a million,” he says. “What matters to me is that I captured this part of history. I want to create awareness: This event is now set in stone, it is in the archives.”

Khader said his documentary has been accused of portraying a one-sided, antisemitic version of the story. He believes that is up to the viewer to decide. “All I wanted was to tell the stories from within, from people who are close to me,” he says.

This combination of the political and the intimate transpires throughout the film, up until the very last scenes, when Khader travels to the seaside with his friends so they can see the coastline for the first time in their lives. Palestinians are not allowed to freely move outside the West Bank – they have to apply for permits first, which take time and are often arbitrarily denied.

Khader and his friends decided to sneak out through an opening in the Israeli West Bank barrier, a wall separating the two territories. It was the middle of the night and they were at great risk of being caught or even shot. “But the sea is, of course, one of those things,” Khader says. It’s a symbol of freedom, of a dream of a better future for all Palestinians. Khader doesn’t say it out loud, but the expressions on the faces of his friends in the film speak volumes.

Scroll down to see more of Khader’s photos: