Edna comes to the door behind a walker, her dog barking. The dog has a sad story, she tells her unexpected visitor: it has liver problems, and she needs to put it down. She’s 86 and has a matter-of-factness about her when she talks about the dog, or how she had to quit driving recently because her “foot wouldn’t go on the pedal”—she hit a tree, the first accident she’s ever had. After a few minutes of introductory chit-chat, she sits down on the seat of her walker and listens to the man at the door. His name is Aaron Marquez, and he’s here because she is one of the most important voters in the country.

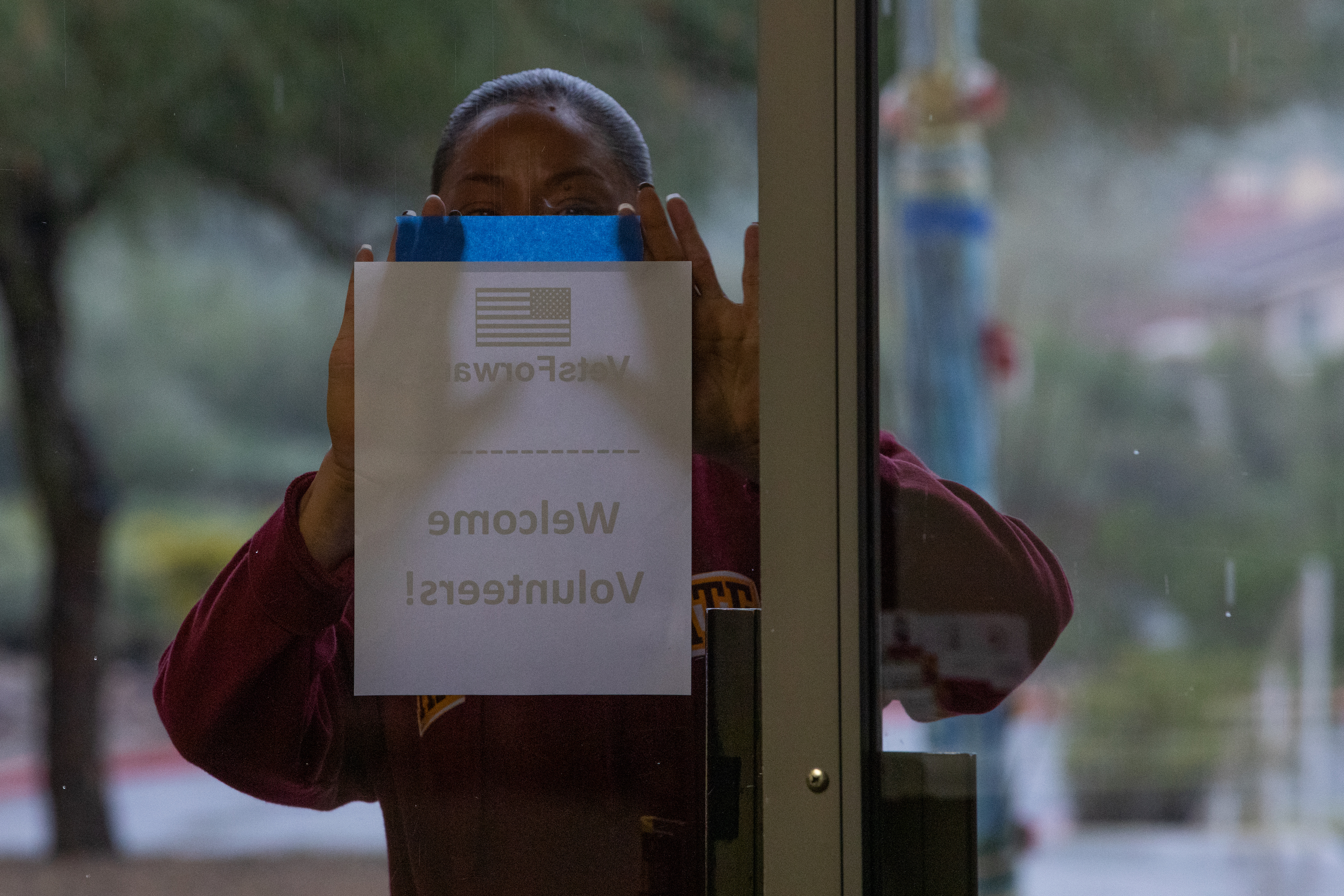

It’s a weirdly rainy February Saturday in Phoenix, weeks before “social distancing” has begun to shape the flow of people’s lives, and I’m going door-to-door with Marquez, a former Army Reserve captain. His other role is that of executive director of VetsForward, a progressive veterans organization that is focusing on electing Democrats in key areas like Arizona’s 20th Legislative District, where Edna lives. (I’ve changed her name to protect her privacy.) For the first time in recent presidential-election history, Arizona is going to be a swing state, and the Democratic candidate for U.S. Senate, Mark Kelly, has a good chance of unseating incumbent Republican Martha McSally. If he did, his could be the victory Democrats need to regain control of Congress’ upper chamber. Republicans also hold narrow majorities in the state legislature, 31-29 in the house and 17-13 in the senate. The 20th district’s senator and two house members are all members of the GOP, meaning Edna’s mail-in ballot will help decide which party controls the presidency, Senate and Arizona legislature. And though she’s a registered Republican, she’s not sure who she’s going to vote for.

Videos by VICE

Marquez’s team is trying to do the hardest thing in politics: change voters’ minds. The way to do that, they believe, is to get deeply, heart-rendingly personal with voters, sharing stories of love and death and prodding the voter to do the same thing, to swap intimate truths with a stranger in the name of building connection.

Marquez starts off by talking about how important it is to protect the ability of people with pre-existing conditions to get health insurance, pretty standard political-messaging stuff. But then he transitions into telling Edna about his dad’s cancer, and how hard he tried to save his life: Marquez donated his bone marrow, and the cancer went into remission, but then it came back. His dad had good medical care, but that wasn’t enough; he died in January 2016.

Marquez says all of this plainly. He’s told this story at many doors, he’s practiced it, and it captures Edna’s attention, though she seems a bit reluctant to take the next step and talk emotionally about any similar experiences of hers. Marquez then pivots, somewhat awkwardly, back to electoral politics, showing her a video on his phone about how Arizona Republicans passed a state law last year expanding the use of “junk” health insurance plans that often don’t cover pre-existing conditions. He tells her that all three of her representatives in the state legislature voted for that bill. “You’re kidding,” she says. When he leaves, she’s still uncertain about how she’ll vote.

What Marquez and others in VetsForward are trying to do is often referred to “deep canvassing,” a technique pioneered by an LGBTQ advocacy group in Los Angeles, and one that has spread across the country: progressives hope it can be used to push Trump-skeptical Republicans like Edna into voting for Democrats. Unlike traditional canvassing, which often emphasizes knocking on as many doors as possible, deep canvassing means being prepared to spend 15 minutes or more with one person, trying to get them to open up.

Trying to connect with people on an emotional level isn’t a revolutionary strategy. “Candidates do that when they talk to voters,” said Hunter Henderson, an organizer with VetsForward. Any good, experienced canvasser will try to make the conversation personal and tell stories. But often, campaigns are more focused on knocking on a large quantity of doors instead of trying to forge a deep connection with every voter. “The purpose of deep canvassing is to be intentional about it,” Henderson said.

On this day, VetsForward was also specifically knocking on the doors of registered Republicans, which they have identified using the voter file, then asking them about their level of Trump support, in order to find the right-leaning voters who were on the fence, like Edna. That’s an odd thing in politics, where many campaigns focus on finding a candidate’s supporters and making sure they vote, not changing their opponents’ minds.

“The way I think about it,” Broockman said of deep canvassing, “is it’s really worth trying, because we don’t know of anything else that works.”

Mark Cardenas is a former Democratic member of the Arizona House of Representatives who has run field operations for many campaigns and sat in on a February VetsForward training. “I like that they’re actually listening to people,” he said. “Canvassing usually is like, ‘I’m talking at you, here’s my candidate, here’s why they’re great. Here’s Election Day, I’ll be back. Do you like him? Yes or no.’ And then I’ll be back after your ballot hits your mailbox to make sure that you’ve dropped that ballot in the mailbox. And that’s it.”

That kind of canvassing, which focuses on getting your own supporters to actually vote, has the virtue of not taking a lot of time per conversation, which is important for organizers focused on a “win number”—the total number of votes they think it’ll take to guarantee victory, Cardenas said. It’s easier and more cost-effective to do turnout-driven canvassing rather than persuade someone into joining your side.

But the strategy of focusing on the Democratic base has arguably been a failure. “The common critique of the Democratic Party for a long time has been, if we win on the coast and you win in a few key big cities, you can win the presidency. But then we’re basically not delivering a Democratic message to folks in Iowa, folks in Nebraska, folks in rural parts of Arizona,” Marquez said. “These are rural communities where they’re getting told the government doesn’t add value to their lives, and we’re trying to show them the government does add value to their lives. And that’s not very different than what I did in Afghanistan as a civil affairs team leader going into a rural Afghanistan village and saying, ‘Hey, I think you should support the central government.’”

Some progressives think that deep canvassing could be part of an effort to win back votes Democrats have lost. In 2018, a group called Changing the Conversation Together (CTC) used deep canvassing in an effort to elect Democrat Max Rose to Congress in Staten Island, the reddest of New York’s five boroughs. Volunteer canvassers went door to door and told prospective voters about someone they loved—even if the story was barely related to politics—and invited the voter to share a similar story, in the hopes of getting that voter to see how their loved ones might be harmed by Republican politics. “The words that are gonna convince people to change their mind are the words coming out of their own mouth,” CTC leader Adam Barbanel-Fried said in a NowThis documentary from 2018. “The real key is listening.” That November, Rose won a narrow 11,000-vote victory over the incumbent.

“I know people can think it sounds like touchy-feely flower power 1967 or something,” Barbeniel-Fried told me, of the techniques deep canvassing uses. “The truth is that if you look at studies that have evaluated what works when you’re trying to change someone’s mind, facts and issues and opinions don’t work. You have to connect. You have to build trust, and you have to connect emotionally.”

The political scientists Joshua Kalla and David Broockman have studied what campaigns can do to change voters’ minds during general elections, and the answer is basically nothing works. Even the most eye-catching campaign ad is likely to be ignored or forgotten; direct mail probably just goes straight into the trash. People tend to reject arguments that don’t already fit into their worldview, no matter how clever those arguments are. It makes sense that candidates generally focus on making sure their own supporters vote, rather than persuading unsympathetic voters to change sides. (Some political scientists now argue, controversially, that turnout is the only thing that decides elections and the persuadable voter is essentially a myth.)

A paper published earlier this year by Kalla and Broockman showcased the results of field experiments where canvassers talked to thousands of people and tried to talk them out of prejudicial attitudes toward immigrants and trans people. Making direct arguments about why these prejudices were bad or unfounded was ineffective, but a “non-judgemental exchange of narratives” (the sort of conversation deep canvassing is meant to spark) “durably reduced exclusionary attitudes for at least four months.”

It remains to be seen how effective deep canvassing is in electoral contests. One problem is that it’s incredibly expensive and time-consuming relative to other tactics, like advertising or direct mail. Deep canvassing involves training volunteers to have intense exchanges with strangers, then sending them out to spend unusual amounts of time with individual voters, in some cases returning to them multiple times over the course of months in an effort to change their minds. And now, with the pandemic limiting the ability of campaigns to conduct any type of canvassing at all, deep canvassing will likely have to be conducted over the phone, meaning canvassers can’t do things like show people videos or use body language. When you deep canvass, you are reaching very few voters, by design, and some of them will be downright hostile to the cause you support—hardly typical campaign tactics.

Even if deep canvassing is effective, it won’t be able to influence enough voters to have much of an effect on the presidential election or major statewide races. But in down-ballot contests, every vote counts; in Arizona’s 28th legislative district, the Republican won the state senate seat in 2018 by fewer than 300 votes. That’s the sort of outcome deep canvassers think they can change.

“The way I think about it,” Broockman said of deep canvassing, “is it’s really worth trying, because we don’t know of anything else that works.”

The origins of deep canvassing can be traced back to 2008, when the anti-gay marriage Proposition 8 passed in California, shocking many LGBTQ activists, including a man named Dave Fleischer. “I had an idea, that maybe if we wanted to understand what had happened, we needed to go out to the neighborhoods where we’d been crushed, we needed to seek out the voters who’d voted against us, and ask them why they did that,” Fleischer said in a 2017 TED Talk.

Thousands of conversations later, Fleischer and his team at the Los Angeles LGBT Center’s Leadership Lab seemed to have hit on a way to make people reconsider their views. Not through argumentation, but through sharing their experiences as a queer person and getting the other person to talk about their own marriage. A 2014 paper published in Science seemed to confirm that this was an effective technique, but that paper was soon debunked as a fraud by Broockman and Kalla—who then conducted their own research and discovered, unexpectedly, that the Leadership Lab’s tactics were working after all.

The pair of political scientists have continued to look into the effects of deep canvassing. In 2018, they conducted a study where some voters were targeted by deep canvassers hoping to persuade them to support pro-immigrant policies, and other voters in a “placebo” group were given pro-immigrant arguments a la a traditional canvass. The results: deep canvassing changed attitudes by an average of around 4 to 6 percent, while traditional canvassing had little effect.

There’s no reason that conservatives couldn’t use deep canvassing techniques, Broockman said—canvassers could talk about having been victims of crimes, for instance, to elicit support for harsh criminal penalties. But it’s progressives who have looked into deep canvassing, possibly because they recently found themselves in a similar position to LGBTQ activists after Prop 8. The 2016 presidential election result was a wake-up call to how many voters were hostile to the Democratic Party, and how many apathetic non-voters the party had failed to reach. Democrats had lost hundreds of state and local offices during the Obama years, and then they lost both chambers of Congress and the presidency. Whatever they had been doing, it wasn’t working.

“I’m 65 years old. I started canvassing when I was 15,” Fleischer said. “I would say that one of the changes in political life in America over my lifetime has been that campaigns have devoted less and less attention and resources to figuring out how to relate to people who aren’t already just like us.”

When deep canvassing works, it doesn’t just improve a campaign’s vote total, but exposes someone to a different perspective.

VetsForward, headed by Aaron Marquez, is a project of Forward Majority, a Democratic super PAC launched in 2017 that focuses on flipping state legislatures in a few key states, including Arizona. It has an even more precise focus: recruiting veterans and using them as messengers for left-of-center causes, a counter to the conservative veterans given large platforms by right-wing outlets like Fox News. Sometimes this means made-to-go-viral video testimonials. On the ground in Arizona, it means going door-to-door and trying to connect with voters who don’t normally support Democrats. In this, vets have a major advantage over other canvassers: even an arch-conservative isn’t likely to slam the door in the face of a progressive in a Marine Corps hat.

The attitude of some people who answer the door, said VetsForward organizer Joanna Sweatt, is, “I still want to tell you to fuck off, but I can’t.”

Like other organizations that deep canvass, VetsForward largely follows the techniques pioneered by Fleischer. After introducing themselves, canvassers ask people to rate their support for something on a scale of 1 to 10. They then connect the policy or election they’re focused on to their personal story, which should take two to three minutes. “The hardest part of deep canvassing is the next step,” Marquez said, which is to ask, “What about you?”

Deep canvassing is mostly successful as a two-way exchange of ideas, where the canvasser expresses understanding even when they disagree with the person, and both participants feel like they’re given space to speak. Ideally, the canvasser should talk for less time than they listen. At the end, the canvasser asks about that 1 to 10 scale again. If someone has moved from an 8 to a 5 in terms of their support for Trump, for instance, that’s a victory. The hope (which is somewhat borne out by Broockman and Kalla’s research) is that the person doesn’t rise back up to an 8 as the memory of the conversation fades.

Part of the strategy is to target people who are already unsure about their support for Trump and the GOP. “It’s not enough, in our mindset, to move someone from a 10 to a 7,” Henderson said—a person who is a 7 is still probably going to vote for Trump. Maybe some 10s could be moved down to a 2 or a 3 over the course of multiple conversations, but VetsForward doesn’t have the staff or volunteers to talk to people several times between now and Election Day. “We want to talk to people who are inherently conflicted,” said Henderson, which is why they look for registered Republicans and ask them questions to gauge whether they might be wavering.

Those who believe that turnout is the only thing that matters might scoff at this door-by-door strategy, but Democrats familiar with Arizona politics don’t think that a turnout-only strategy can turn the state blue or flip contested legislature seats.

“In Arizona, we honestly don’t have enough supporters,” Cardenas said.

Two days before the canvass that took us to Edna’s door, I sat in on a training session for VetsForward volunteers. Normal canvassers can be given a script and immediately sent out into the field for on-the-job training, but since these conversations involve personal stories, volunteers needed time to figure out what parts of their life they could share, and to practice opening up to strangers.

Henderson told his story to the group he was training: 12 years ago, his dad died of a heart condition, which not only devastated the family but put them into medical debt that Hederson’s mom is still trying to repay. Since then, Henderson has been diagnosed with the same heart problem, a preexisting condition that, before Obamacare, would have made insurance much more expensive, or impossible to get.

Volunteers then shared their own stories. One talked about a nephew whose allergies were so severe that it was running up huge healthcare costs for his mom. A woman talked about her fiancé, a veteran who, while dying of cancer, spent hours and hours on the phone with insurers trying to avoid leaving medical debt behind. She can barely talk about this and breaks down midway through telling her story—she’s clearly not ready to go door to door and lay out that all in front of someone she’s never met.

This underscores one of the challenges of deep canvassing, which is that it uses up a lot of time, a particularly precious resource to political campaigns counting down the days until the election. Training takes time. Having long conversations takes time. And though VetsForward’s strategy of targeting registered Republicans occasionally finds persuadable voters, they also run into plenty of immovable ones. The same canvassing session where Marquez talked to Edna, he talked to an older Trump voter who was polite but disinterested, as if the veteran were a salesman. “I’m trying to figure out where we’re going with this,” was his response to Marquez’s story about his father dying of cancer.

The 10 or 15 minutes spent with that kind of unpersuadable voter is another reason that deep canvassing is such a time-consuming tactic—VetsForward staff told me they were trying to figure out how to cut conversations short when there is little sign they will be productive. But they also said that just presenting Republican voters with a viewpoint they don’t hear often could be valuable in perhaps unquantifiable ways.

“Whether they move on the scale or not, we’re planting the seeds of doubt,” Marquez said.

The pandemic has created a new wrinkle for progressives like Marquez trying to change minds. Going door-to-door to have conversations is a risk for both volunteers and their targets, so the VetsForward team has started reaching out to voters by text, with the hope, Marquez said, of “seeing if we’re able to move somebody from a text messaging conversation up to a deep phone bank conversation.” Being face-to-face isn’t a requirement for deep canvassing to work: An experiment from Kalla and Broockman found that phone conversations of the sort that deep canvassers have were successful at reducing prejudicial attitudes even though canvassers in that experiment didn’t have the advantages that face-to-face contact can bring.

At the same time, the COVID-19 outbreak may have rendered deep canvassing less necessary. As the Trump’s administration’s incompetent response to the pandemic has become more obvious, many Americans, even normally conservative older whites like the voters VetsForward has doorknocked, have soured on the president, according to recent polls. That opens the door to the possibility of a genuine blue wave, assuming dissatisfaction with Trump lasts, and leads voters to vote Democratic down the ballot. That’s how a lot of voters’ minds change—not through careful, targeted persuasion, but because events alter public opinion on a mass scale.

Fans of deep canvassing often portray it as an electoral tactic, a tool progressives can use to flip those elusive suburban voters to the right side. But maybe more importantly, it’s an opportunity for volunteers and canvass targets both to speak and listen to people they don’t usually talk to, and probably don’t understand. When deep canvassing works, it doesn’t just improve a campaign’s vote total, but exposes someone to a different perspective. Canvassing done by Fleischer’s Leadership Lab exposed people prejudiced against LGBTQ individuals to conversations with actual queer people who knocked on their door and not only opened up, but seemed genuinely interested in what they had to say. Set aside the political science research for a moment and consider the evident power of that: How often does a stranger come up to you and ask, Who and what do you love, and why?

Maybe it will prove to be very difficult to move someone on that 10-point scale to the point where they actually change their vote, so difficult that deep canvassing ends up not being a cost-effective method of campaigning. But even if a deep canvasser doesn’t flip a voter, they often still provide them with new information, as Marquez did for Edna. Even if that person doesn’t reconsider their beliefs, it surely does them good to come into contact with a political opponent who treats them with dignity. And maybe something similar happens to the canvasser, who has to listen to and engage with someone who has views they probably consider wrong, misguided, or even hateful. Persuasion is the goal of deep canvassing, but the process of opening up to a stranger about your personal politics has its own kind of power, even if that power is hard to measure.

Adam Barbanel-Fried of Changing the Conversation Together believes deep canvassing could help deliver Democratic wins in swing areas. But he’s also seen how much having these conversations has meant to CTC’s volunteers, how they have found something they may have not known they needed.

“There’s a whole world of people that are hungry for meaningful, authentic conversations with people outside of their normal day to day life,” said Barbanel-Fried. “We have all found ourselves transformed by some of these conversations.”

Harry Cheadle is a freelance journalist who writes a newsletter about failure. Follow him on Twitter.