Last week I published a story with the headline “Either This Data is Incorrect, or These Physicists Just Changed the World.” Shortly thereafter, my inbox was overrun with emails about the story that weren’t about content of the article, but rather the grammatical error in its headline. As these irate grammarians went out of their way to remind me, “data” is a plural noun so the headline ought to read “Either These Data Are Incorrect, or These Physicists Just Changed the World.”

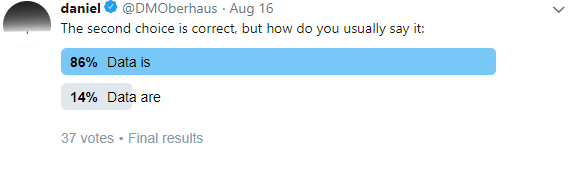

They’re not wrong. The problem is that the grammatically correct version of the headline sounds affected as hell because it isn’t the way people actually speak. This is the reason my editors didn’t change the headline before publishing and the reason we’re not going to change it now. An informal Twitter poll suggests our intuition was correct:

Videos by VICE

This is admittedly a small sample size, but I think the trend it illustrates is clear enough. This doesn’t mean that people feel any less passionately about the grammatical status of “data,” however. In fact, the Wikipedia entry for “data” notes that the word has “generated considerable controversy,” which is pretty surprising when you think about other words that might be labeled controversial.

The controversy stems from whether or not data is to be considered a countable or uncountable noun. As an uncountable noun, it can be used with verbs conjugated in the singular form, but historically it is considered the plural form of the countable noun “datum”, which is Latin for a “thing given” (i.e., “There are 69 datums”).

When I spoke with Peter Sokolowski, a lexicographer for the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, he told me that data’s transition between its historical roots and contemporary use is related to a lexical phenomenon called “semantic bleaching,” where a word’s original meaning is lost or diminished over time. An example of semantic bleaching include the contemporary use of the word “literally,” whose Latin root, littera, means “letter.” In the case of “data,” it has transitioned from “things given” to mean something like “a collection of information in aggregate” when used in everyday speech.

According to Jane Solomon, a lexicographer for dictionary.com, the use of “data” in the singular dates back to the early 18th century.

“In my professional opinion,” Solomon told me in an email, “that’s enough time for this use to be considered a part of standard English.”

Solomon said she understands the desire to correct people on their use of language. Prior to the mid-twentieth century, linguistics was dominated by a prescriptivist paradigm, which sought to delineate the correct use of language. At the same time, Solomon said, the English language was contending with grammarians who wanted to “Latinize” the language.

“This led to the creation of grammatical rules that don’t make much sense in the context of English,” Solomon told me, citing rules against ending sentences with prepositions as an example of this phenomenon. “This use is very common in English, however, and most people would consider ending sentences with prepositions completely grammatical.”

While prescriptivism has its uses, particularly when it comes to establishing communication standards within organizations—for instance, the style guides used by many news organizations or the syntax of a programming language—it also has plenty of weaknesses.

Read More: ‘Crypto’ Means Cryptography, Not Cryptocurrency

For one thing, natural languages are constantly changing and any attempt to nail them down with a set of hard and fast rules is bound to distort how that language is used in practice. (This hasn’t stopped some language groups, like Francophones, from creating organizations dedicated to keeping their languages pure, however.) Moreover, any given language usually has a collection of dialects and choosing one dialect as “correct” has historically been wielded as a political tool that often has racist and classist motivations.

“When we talk about English that is ‘correct’ or ‘standard,’ we’re talking about one specific register of English that is used in certain formal contexts,” Solomon said. “Non-standard English also follows a set of sophisticated rules and patterns, though it’s easy to overlook this if you don’t understand the basics of how language works.”

In the mid-twentieth century prescriptivism was supplemented with linguistic descriptivism, which aims to catalog the ways language is used in practice—like using data as a singular noun, for instance. Indeed, Sokolowski pointed to the Merriam-Webster entry for “data,” which notes that both singular and plural constructions are “standard” in English. Thus, Sokolowski told me over Twitter, “anyone who ‘corrects’ you for noncount use of ‘data’ is being pedantic (and probably rude).”

It’s the job of lexicographers like Solomon and Sokolowski to determine what is considered grammatical based actual usage when compiling a dictionary entry for a word. But at what point is the usage of a word considered widespread enough to warrant inclusion in a dictionary?

According to Solomon, lexicographers use language corpora—large collections of written material—to analyze how language is used in practice and determine what should be included in a dictionary. She pointed to the NOW corpus as an example, which contains 5.9 billion words drawn from 20 different English magazines since 2010. It is the largest language corpus available and grows by around 4 million words everyday.

Solomon used the NOW corpus to look up what verbs are most likely to follow “data” and found that “is” is over seven times more likely to appear after “data” than “are,” so people reading the news are far more likely to encounter the allegedly ungrammatical use of “data” than the grammatically correct version. In short, the use of “data” has clearly changed in popular speech and it’s time to acknowledge that.

“People who take the time to learn grammatical rules in school can sometimes get very, very attached to those specific rules,” Solomon said. “While grammar definitely helps us communicate in a way that can be understood by our audience, it’s not at all set in stone from when we learned in grammar school. Dictionaries are a work in progress.”