Twelve years ago, a criminal justice master’s student named Philip Stinson got into an argument with his grad school classmates about how often police officers committed crimes. His peers, many of whom were cops themselves, thought police crime was rare, but Stinson, himself a former cop and attorney, thought the problem was bigger than anyone knew. He bet a pint of ale that he could prove it.

On Tuesday, Stinson made good on his bet with an extensive police crime database offering the most comprehensive look ever at how often American cops are arrested, as well as some early insights into the consequences they face for breaking the laws they’re supposed to enforce.

Videos by VICE

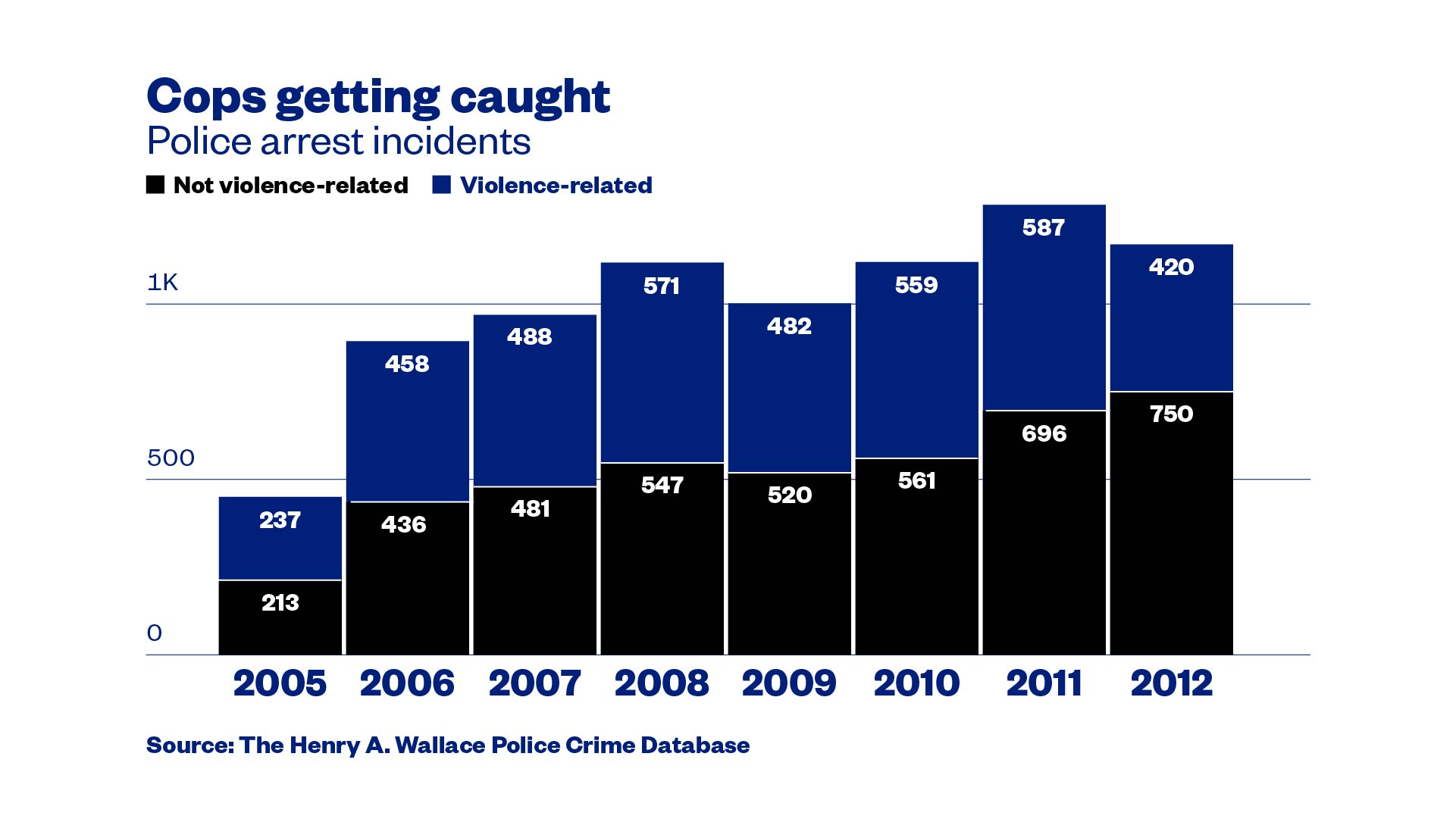

The data set includes 8,006 arrest incidents resulting in 13,623 charges involving 6,596 police officers from 2005 through 2012, with more years of data to come. Nearly half these incidents, Stinson and his research team concluded, were violent.

The data covers 2,830 state, local, and special law enforcement agencies across all 50 states plus Washington, D.C. That’s just a fraction of the approximately 18,000 law enforcement agencies and 1.1 million sworn officers in the U.S., so the data set is not comprehensive, but it’s the most extensive and ambitious look at cop crime to date.

“It’s not as rare as you might think. It happens at all stages of officers’ careers, and at all ranks,” Stinson said.

Police misconduct — and seeming impunity — has drawn increasing scrutiny in the United States since the 2014 protests in Ferguson, Missouri. Stinson, who is now an associate professor of criminology at Bowling Green State University in Ohio and a leading expert in the field, has contributed to earlier national efforts to track police misconduct and is the go-to resource for information on police violence. This new database, shared first with VICE News, is the only public effort that attempts to track all alleged crimes by police.

The federal government doesn’t collect data on most arrests or convictions of police officers, in part because such an endeavor would have to rely heavily on self-reporting from law enforcement agencies. Stinson tracks these incidents using a combination of media reports and court records.

The topline numbers indicate about 1,000 officer arrests per year over the eight years of the data set, and nearly 1,140 arrests per year from 2008 through 2012. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that police crime has increased since 2005, or gotten more violent. Stinson’s methodology has become more sophisticated over the years, and it’s possible the figures could change because of variations in the search algorithms he uses to find cases.

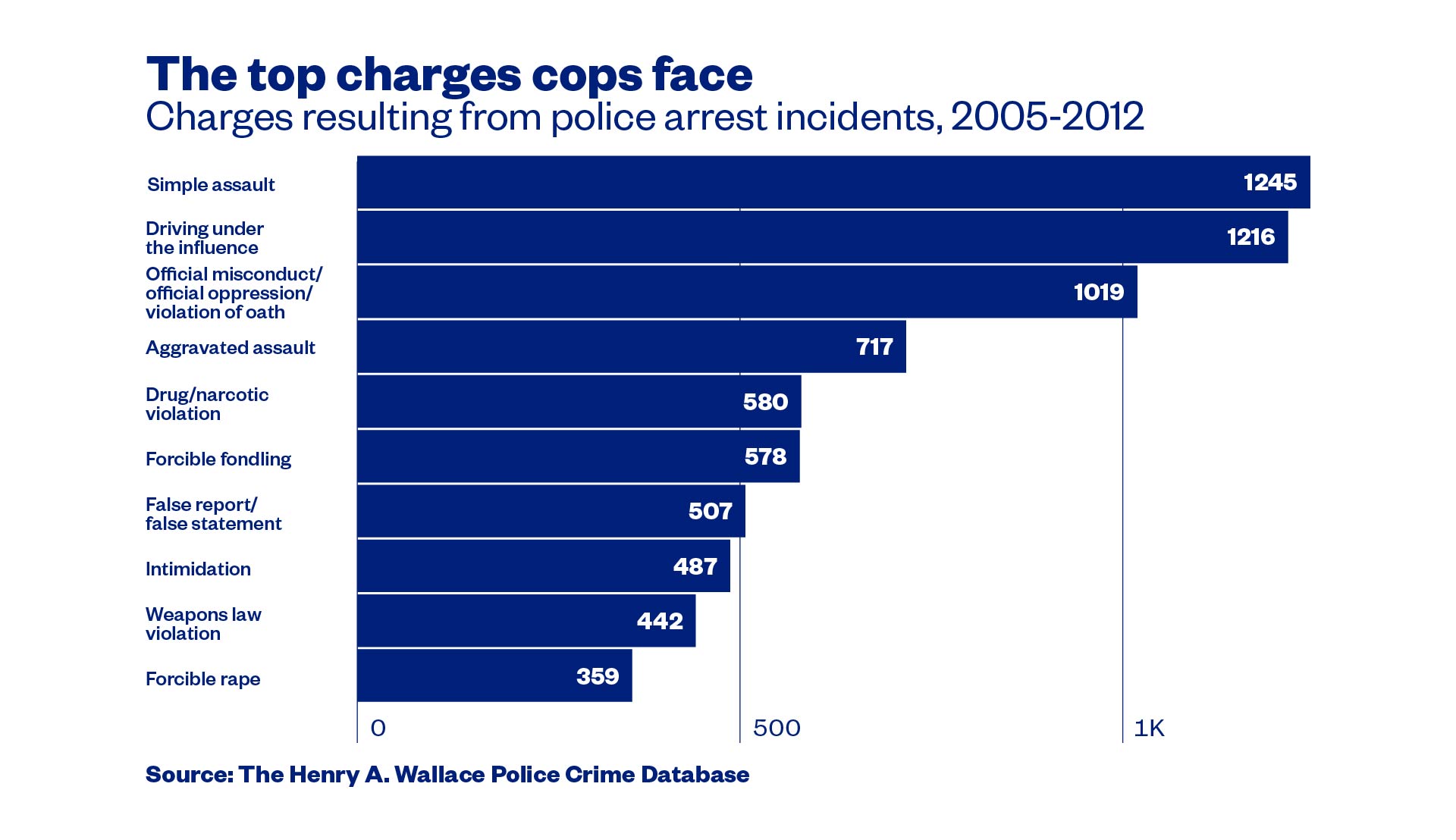

The most commonly charged offense across all police arrest incidents in the database was misdemeanor assault, with driving under the influence a close second. Forcible fondling and forcible rape also made the list of the top 10 charges.

Stinson and his team track the outcome of whole cases but not whether individual charges result in a conviction. This means we can’t use his data to determine how often cops are convicted of specific crimes.

We should also bear in mind that an arrest is not equivalent to a conviction. Just as with the general population, officers are presumed innocent until proven guilty. But Stinson thinks looking at arrests is a fair way to examine cop crime, because that’s how law enforcement (including the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report) collects information on crime in general.

The database has the potential to transform the way the public thinks about police misconduct and criminal activity. Stinson expects other criminologists, reporters, and law enforcement officials will use the information for research, and he envisions members of the general public using it too. The database is searchable online and users can generate state- and county-level maps and search by crime — such as drunk driving, sexual assault, planting evidence, drug trafficking, and using excessive force on a civilian, to name a few.

Norm Stamper, a former Seattle police chief and longtime officer for the San Diego Police Department, said there’s merit in taking a national look at criminal behavior among cops. Stamper contends there is a culture of impunity within law enforcement that hasn’t really changed since he started his career in 1966.

“There’s a tendency on the part of too many officers to abuse their authority,” Stamper said. “Too many officers whose first impulse is to cover their asses and try to cover up the misconduct or the crime. Too many supervisors who look the other way.”

Stinson hopes that people will look at the data and understand that police crime isn’t isolated or infrequent. “What they don’t realize is that this shit is happening in communities across the country every day,” he said.

An overview of cop crime

Law enforcement experts reached by VICE News weren’t surprised by Stinson’s findings, especially the top three most common charges. They pointed in particular to the prevalence of domestic violence among cops, which studies have shown occurs at a rate two to four times higher than in the general population.

Seth Stoughton, an assistant professor with the University of South Carolina School of Law and a former officer in the Tallahassee, Florida, police department, said that while officers might have turned a blind eye to their peers driving drunk or beating their spouses 30 years ago, when society as a whole was more accepting of both crimes, that isn’t the case today.

“There’s been a lot of pushback on giving officers a pass for those things,” he said. “Those are the ones where we’ve seen significant shifts in public opinion.”

1,219

officers were arrested for sex-related crimes from 2005 through 2012.

- More than half of the alleged victims were underage — 17 or younger.

- The most common sex crime was “forcible fondling” (388 cases), followed by “forcible rape” (355 cases).

- 17 percent of the officers arrested for sex crimes (213 cops total) were charged in multiple sex-related cases, meaning they were either repeat offenders or had multiple victims.

846

drug-related arrests occur in the data from 2005 through 2012.

- 227 of these involved more than one drug.

- The most common drugs involved in these cases were cocaine (251 charges), marijuana (202 charges), and the prescription opioid oxycodone (110 charges).

- Opioid-related charges increased from 2005 through 2012, but the sample size is small: There were just 11 arrests involving opioids in 2005, which grew to 55 by 2012, driven largely by the prescription painkillers hydrocodone and oxycodone.

Drug violations are by far the most common arrest category among U.S. civilians. In 2012 alone, there were more than 1.5 million arrests for drug violations. Cops, on the other hand, are much less likely to be arrested for abusing or possessing drugs. Jonathan Blanks, who heads the Cato Institute’s National Police Misconduct Reporting Project, said the difference may have to do with the fact that most law enforcement agencies regularly screen their employees for drug use, so fewer officers use drugs than their civilian counterparts.

1,019

of the arrest cases involved charges for “official misconduct,” “official oppression” (a fancy way to say abuse of power), or violation of oath. Because doing anything illegal is a violation of the police code of conduct, these charges often get tacked on to other offenses. “It’s thrown in with the kitchen sink,” Stinson said. These were the most serious offenses charged in only 15 cases.

What we don’t know about police crime

Stinson makes it clear that his database does not capture the full extent of crimes committed by U.S. police officers. First, it covers only eight years and more recent data hasn’t been fully coded yet (his team hopes to complete 2013 data by later this fall, with more years added after that).

Another reason is that not everyone who commits a crime gets caught — and many criminal incidents involving police officers, in particular, don’t end in an arrest or charges. In some departments, cops enjoy a certain amount of “professional courtesy” from their fellow officers, Stinson said — rather than arrest a colleague for driving drunk, an officer might look the other way, or even drive him home.

This idea is in line with Stamper’s experience in the San Diego Police Department. “It was understood that when you stopped a police officer off-duty, if you rolled up to his home on a domestic violence call, you would extend professional courtesy,” Stamper said. “Over time, many police departments have corrected that; they’ve come to the realization that it doesn’t just look bad — it is bad.”

Tracking police crime

Since 2010, 49 student research assistants at Bowling Green have worked in Stinson’s research group, helping to code and shape the data. They gather the data on arrests primarily through media reports, which they find using 48 different Google alerts — variants of “police officer was arrested,” “detectives were indicted,” and “trooper was charged,” for example.

Researchers code each case in this database with up to 159 variables — things like the officer’s age, rank, and years of service, and the type of crime, location, gender of victim, and whether the cop was on or off duty. They then set up alerts for each case both in Google and legal document databases in order to track what happens to an officer as he moves through the criminal justice system.

Efforts by the federal government to track arrest-related deaths have also incorporated open-source data such as news reports, due in part to the unreliability of law enforcement agencies self-reporting crimes or wrongdoing.

James Lynch, a former director of the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics and now a professor at the University of Maryland, said there’s a simple explanation for why the government doesn’t track police misconduct more broadly. “You’re asking the police to tell you about the sins of their workplace,” he said. “I suspect that they wouldn’t expect high levels of compliance. The data quality would not be good.”

Lynch cautioned that Stinson’s Google alert system is a relatively new technology, and new technology can be flawed. “It’s a legitimate method,” he said, ”but it’s not foolproof.”

Other experts said that credible media reports are a good foundation for this kind of research because journalists do some of the work to verify the incidents.

“While news searches will not collect all misconduct, particularly internal misconduct that is handled administratively and away from the public eye, the stories can be tracked to see how the cases are resolved through the criminal, administrative, and civil processes,” said the Cato Institute’s Blanks. “While imperfect, tracking misconduct like this is a public service to try to hold police accountable to the public they serve.”

What we know about these cops

Years of service

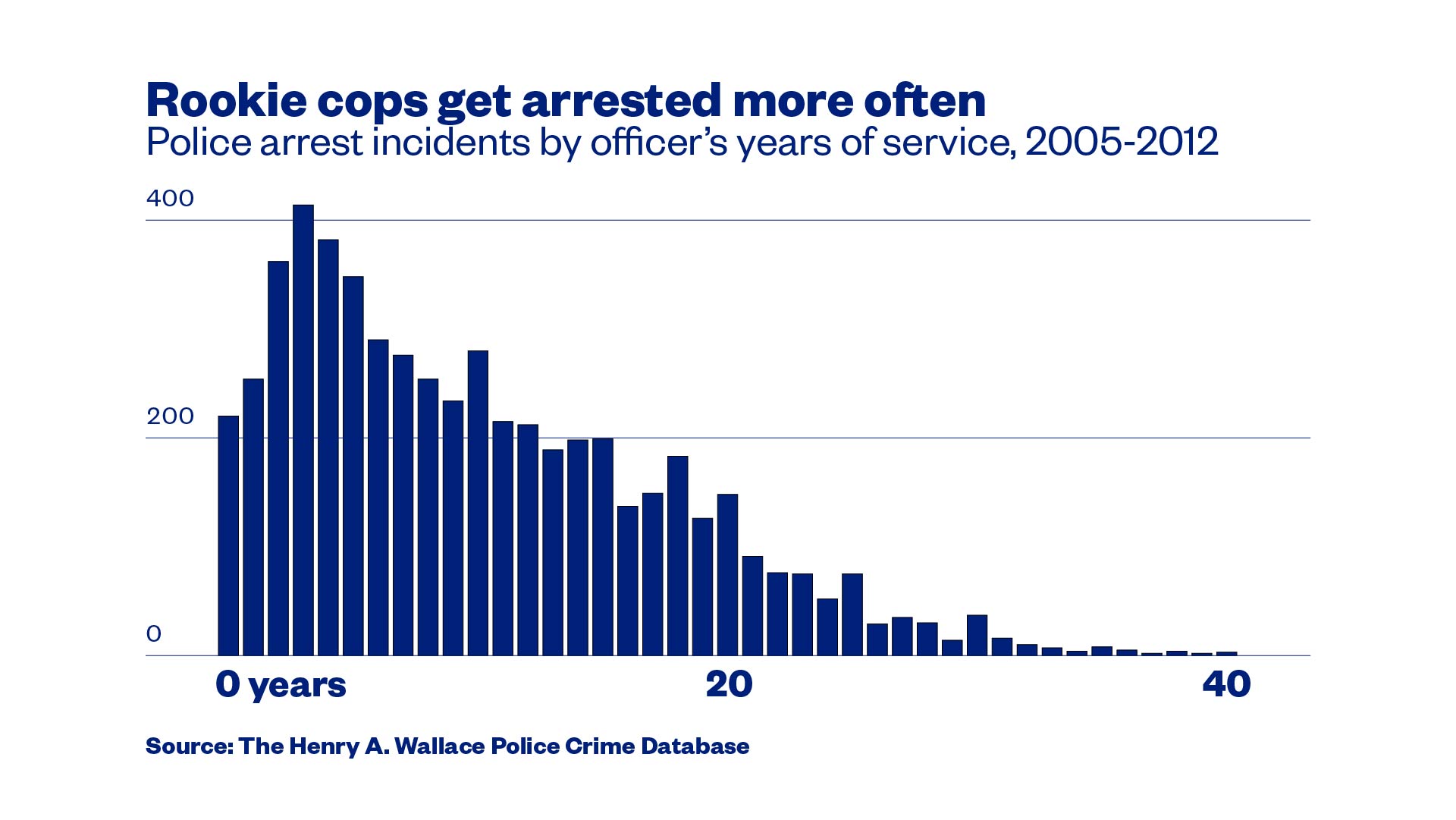

- Stinson’s data is in keeping with previous studies linking rookie cops to professional or personal misconduct. One study from 2008, for example, found that inexperienced cops were more likely to use deadly force than their veteran counterparts.

- Yet it doesn’t seem like the types of crimes cops commit vary much by age or experience; police officers in their first four years on the job were arrested for the same crimes as veteran cops.

Officers’ gender

- Most cops who got arrested — like most officers overall — were men: 93 percent, or 6,176 in total.

- 13 percent of the most serious charges male cops faced were for misdemeanor assault.

- Just 7 percent of arrested officers were women — 429 in total. The most serious charge female officers faced most often was drunk driving, accounting for roughly a fifth of all charges.

Repeat offenders

- Out of the 6,596 officers in the data set, 802 were arrested more than once. This could mean multiple arrests spread across many years, or it could mean a cop faced criminal charges relating to more than one victim stemming from a single arrest.

- Stinson’s team also found that nearly a quarter (24 percent) of the officers arrested for any crime from 2005 through 2011 were sued at some point during their career for federal civil rights violations, like excessive use of force or verbal harassment. These suits may have come before or after the officer was arrested and might be entirely unrelated, but they could also be a proxy for whether an arrested cop is just having a difficult moment or really is a bad apple. “This suggests to us that these are bad cops,” Stinson explained. “These aren’t just one-offs where they get in trouble.”

When cops get convicted

Stinson and his team track the outcome of these arrest incidents to see how often they result in a conviction, though they don’t have public data yet on which charges lead to convictions. (The exception is for murder and manslaughter.)

Out of 5,148 cases where Stinson and his team know the outcome, 3,716 (or nearly three-quarters) resulted in a conviction. But Stinson said this conviction rate might be misleading — especially when it comes to serious crimes.

A felony conviction, for example, would likely end a cop’s career because convicted felons typically lose their right to carry a gun. So an officer arrested on felony charges may plead guilty to a misdemeanor charge instead, in order to keep his gun — and his job.

When cops face other consequences

Stinson and his team track whether officers who are arrested lose their jobs, in addition to the outcomes of their cases. He knows that at least 91 percent of convicted offers were fired or resigned. The picture for all arrested officers is unclear — it seems they lost their jobs in a little over half of cases where Stinson was able to determine what happened.

“I always assumed that if an officer gets arrested, their career was over,” Stinson said. “What we’re seeing is that this is not the case. Many of these officers don’t get convicted, and many of them who actually leave their job, lose it, or quit, end up working as police officers elsewhere. So there’s a sort of officer shuffle that goes on.”

That’s because it’s pretty hard to fire a cop, even one who’s been arrested — and a lot of that has to do with the strength of the police unions, whose contracts often dictate when a department can fire an officer. Some say a cop can be fired only when he’s convicted of a crime. In other cases, that conviction has to be for a felony.

What’s next?

After spending more than a decade with the data, Stinson thinks he was right about police misconduct being a systemic problem, and he thinks there are a couple of important explanations. One is what he sees as an entrenched attitude within American law enforcement that allows cops to think they can get away with almost anything, because police officers protect one another.

But Stinson also thinks that law enforcement officers don’t receive adequate support to cope with the stresses of the job — and that can cause some of them to turn to crime.

“We see signs where it’s obvious to us that people are unraveling personally and professionally, and we’re left scratching our heads wondering why their agencies hadn’t gotten them help they need,” Stinson said, pointing to cases where officers were arrested multiple times within a short period. “You know clearly there are all kinds of things going wrong in their life with post-traumatic stress, with mental health issues, with addiction issues, alcohol issues, drug issues.”

Stinson doesn’t want the public, or police, to come away from the database thinking that it’s inherently critical of law enforcement — that was never his intention. He hopes that it might offer an opportunity for introspection among officers and even spotlight cops’ need for improved support.

CORRECTION (Sept. 12, 10:47 p.m.): An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the police union contract for officers in Los Angeles stipulates that officers can be fired only if they are convicted of a crime. There are multiple reasons why an LAPD officer can be terminated from the force. In the event of an appeal, an internal review board decides whether an officer stays on the force.

Isabella McKinley Corbo is an associate producer for VICE News Tonight on HBO. Tess Owen is a reporter for VICE News.

More

From VICE

-

(Photos via Softulka / Getty Images; Baltasar Engonga / Facebook) -

(Photo by Jens Büttner/picture alliance via Getty Images) -

Savannah Sly, dominatrix and co-founder of sex-worker vote mobilization group, EPA United. -

(Photo by Manuel Weis / Getty Images)