Bangladesh is one of the fastest growing economies in the world. And while this can be good news in the long run for the livelihood and stability of the country, the growth also means the population is expanding. About 65 percent of the country’s population lives in rural areas, most without reliable hospitals or medical services nearby. That lack of resources—both in the form of emergency response as well as more longterm medical care—has created a set of dire circumstances. Solutions are coming from somewhat unlikely places: Recent grassroots efforts are taking victims of a failed system and arming them with skills needed to save lives.

One of the dire circumstances stemming from lack of medical care: maternal mortality. Each year, 5,200 women die due to pregnancy and childbirth related issues. To add to the health concerns, two out of every three girls get married before they turn 18, and teen pregnancy is pervasive. And while 64.9 percent of married adolescent girls report not wanting a child in the next two years, only 55.3 percent of them are currently using any method of contraception—largely due to a lack of family planning services and health information.

Videos by VICE

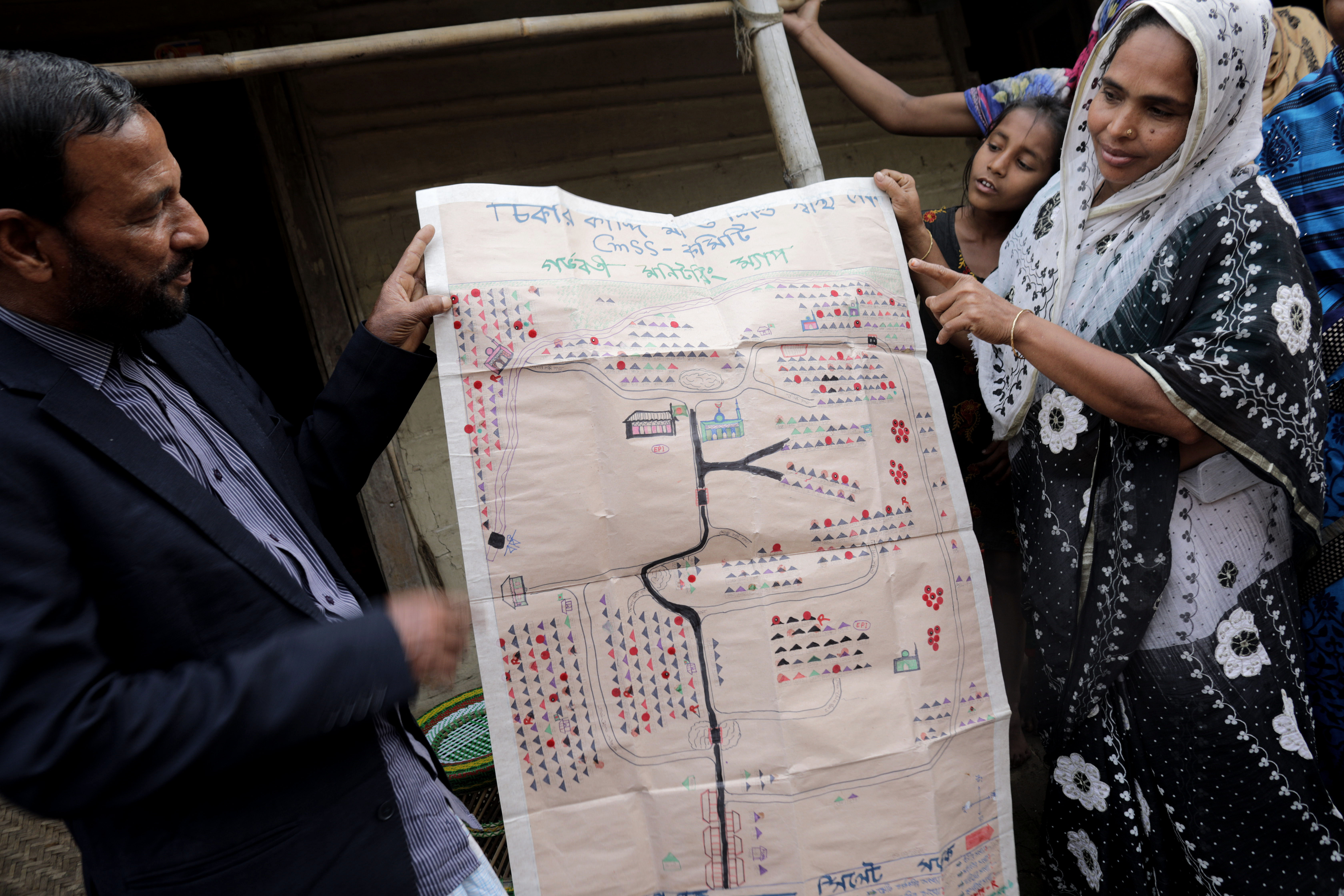

Amena isn’t technically a doctor. The 37-year-old mother of three has no formal education past high school, but she wears a white coat and stethoscope and everyone knows her as the village healer. For the last year she has been going door-to-door to 7,500 homes in Sumagang, making sure pregnant mothers are healthy and prepared for birth. She and the village elders track where expecting mothers live as well as homes with children inside using a map they made themselves on parchment paper with markers to denote different types of households with different colors.

Trained in basic maternal health by a partnership between the Bangladeshi government and Glaxo-Kline Smith, Amena is the only person in the area with the skills needed to provide basic prenatal care. That can be the difference between life and death for moms who often don’t know if that they are at risk.

While rates of maternal mortality in Bangladesh have dropped dramatically over the past ten years, the rates in the northern province of Sumagang are still twice the national average.The fixes are often simple: Trained birth assistants to prevent bleeding during labor, iron tablets (which are affordable, but not widely accessible) to help with anemia, which mothers commonly acquire when having many babies in a short period of time.

More From Tonic:

Even when childbirth goes safely and as planned, children can have the risk of falling into the country’s stunting problem—meaning they may not grow to healthy heights because of chronic undernutrition. Stunting often leaves 11-year-olds looking like 8-year-olds. Perhaps the hardest part about this prevalent issue is that because it’s so common people don’t recognize it’s a problem at all. “If every child in the same village is malnourished and no children are actually a healthy height, it becomes hard to decipher there is anything abnormal,” says Rina Paul, Bangladesh local and researcher for CARE, a global organization committed to ending poverty through economic empowerment and health initiatives.

Throughout Bangladesh and the rest of the global south, the stunting issue could be eased by raising awareness about the importance of vegetables that they can afford and are accessible. Amena and the other 600 Skilled Health Service providers across rural areas of Bangladesh help educate new mothers on nutritional health, but also check blood sugar, do pregnancy tests, look for jaundice and refer any serious issues they find to the closest health facility.

Amena’s role doesn’t just help the villagers, it changed the way she saw herself the power she had as a woman in her family. Her income from selling the medications—where prices are offered on a sliding scale depending on what people can afford—has given her power and a voice inside her family. Before she got her white coat, Amena stayed home with her kids while her husband worked on a farm. But when she heard about the six-month training program, she jumped to take the qualifying exam.

“I am educated, but before this I was kind of non-functional,” she says. “I wasn’t doing anything other than cooking and household work, so then I thought, if I apply for this, it will give me an opportunity to work and also help others. My husband now values me and I have a strong ground in my family. He sees me differently. It is inevitable, when you have an income, you have power. I even saved some money this month to buy myself a present; I would never have done that before.”

While Amena has made a difference for women and the health of their babies in her village, her limited training can’t fix everything. “Sometimes, when I go to do a health check, I find it’s really serious. I’m not a doctor. When that happens, all I can do is refer them to the closest facility to make sure they stay safe.” she says.

Since the program started, there have been 22,000 skilled safe deliveries performed by 3,000 workers trained across the country. This same program has been replicated in Afghanistan, Cambodia, Chad, Laos, Myanmar and Nepal.

Another grim reality of a growing economy and population is the traffic problem in the capital city of Dhaka—a result of city planning not designed to support the now almost 15 million people who live there. Those not stuck in some of the world’s worst traffic are vulnerable to a different risk: becoming a roadside statistic themselves.

Accidents caused by a lack of enforced road rules and reckless driving are on the rise not only because of growth, but also a lack of proper services, like reliable ambulances, or a national hotline like 911 or reliable ambulatory service. As one local paper recently reported, 22 people were killed on the road in one 24 hour period this past February. The World Health organization estimates there are 20,000 deaths on the road every year, and joint study by the Accident Research Institute and the Center for Injury Prevention and Research noted that 65 percent of those deaths happen on the spot, while 35 percent happen within two hours.

When American emergency room doctor Jon Moussally saw this firsthand when visiting in 2012, he also noticed the abundance of bystanders trying to help but often failing. “It occurred to me when seeing the rate of fatalities and people around, that with with a few supplies and basic training, they could be saving lives,” he says.

So he started TraumaLink, a emergency volunteer service for victims of roadside injuries. The services recruits and trains people who work and live along a stretch of highway outside Dhaka, where many traffic related incidents occur. Fruit sellers, gas station workers and the like participate in a two-day course with hands-on training led by a physician. With distributed first aid kits, these roadside business owners become makeshift EMTs who are able to help stop bleeding, which is a leading cause of death at the scene. They then coordinate transport to medical facilities.

TraumaLink also created a 24/7 hotline serving as a makeshift 9-1-1 for bystanders and victims to call, with operators quickly identifying the location of the crash and number of parties involved. Using a software program, it sends a text message to all qualified volunteers in the area. 500 volunteers have been trained and responded to 260 accidents, treating almost 450 since the program started in 2014. “Our goal is to continue expanding our operations to create a national service, focusing first on the major rural highways where most fatal crashes are occurring,” Moussally says. “The speed at which we’re able to do this depends primarily on our ability to access funds.”

While it takes time for Bangladesh’s infrastructure and government to catch up with its economic growth and booming population, makeshift medical heroes like Amena and those training under TraumaLink are gaining more traction to fill the gap in the best ways they know how, one patient at a time.

This reporting made possible by a CARE Learning Tours sponsored by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Correction: A previous version of this story says that Moussally funded Trauma Link through an Harvard/South Asian Institute Grant.

Read This Next: Why Our First Responders Are So Burned Out