On a Friday afternoon in late July, Bethany Beal and Kristen Clark stepped onstage inside an empty convention center in San Antonio, Texas, to kick off the first day of their annual summer conference. If not for the pandemic, the seats would have been filled with approximately 600 teenaged girls and their mothers, all hoping to grow as women in the eyes of Christ.

The event, which began five years ago under the title “Radical Purity,” is an extension of the sisters’ highly visible online ministry Girl Defined, a collection of blog posts, videos, and instructional books aiming to provide mentorship to young Christian women. The name refers to Beal and Clark’s foundational message—that one must work against the odds to be “a God-defined girl in a culture-defined world.”

Videos by VICE

Their ministry doesn’t say exactly what it means by “culture,” but those who follow Girl Defined understand the subtext. The pursuit of Christian girlhood is more difficult than ever. The church has bent to the will of progressive ideologies. Traditional ideals of femininity are seen as outdated, if not offensive to the general public. Purity has been traded in for a blanket ethos of “sex positivity.”

But faced with a country renegotiating its relationship with a biblical God, Beal and Clark are hopeful in their virtual conference, which was live-streamed to a private audience of some 800 girls on Facebook.

“God is looking for courageous women like you to go against the grain of modern culture,” Clark said in the opening session. “He is looking for brave women who will set a new trend, think outside the box and raise the bar for femininity. He needs women who refuse to live for the applause of this world, and instead live for the applause of their King.”

Sheltered from outside judgments, Beal and Clark began to present a new way forward for each woman watching, a vision of life where the burdens of conservative conviction did not have to be faced alone. Here, there would be strength in solidarity. All of the difficulties of evangelical girlhood would be addressed by women who worshipped in the same way.

For the better part of the past decade, Beal and Clark have worked in the influencer realm, moving from their early twenties to their early thirties with an audience that remains, in their estimation, around 18. The pair are only a year and a half apart, raised in a family of 10, and were homeschooled all their lives, plugged into the church and church life in a way that made them natural communicators. There is almost no online platform the sisters have not participated in at one point or another, but their mission has stayed largely consistent—young Christian girls deserve role models who don’t mince words, and Beal and Clark know they have a knack for getting through to them.

Their first online venture, the now defunct website bairdsisters.com, landed flat, but the vision was there. In 2014, Beal and Clark rebranded as Girl Defined—Clark’s idea—and narrowed their focus to the issues that mattered to high school and college aged girls, namely sexual politics and temptation. From there, it all seemed to fall into place.

A few months after the launch of the new blog, Clark wrote a post that quickly funneled traffic to the site and set the tone for the content to come: “Why Christian Girls Post Seductive Selfies.” It was both confessional and prescriptive, with Clark describing coating on makeup and waiting for the wind to blow in the right direction for a Facebook photo shoot until she turned to Ephesians and realized the error in her vanity. The post was noticed by Baker Books, a Christian publishing house, and led to the release of the sisters’ debut novel Girl Defined: God’s Radical Design for Beauty, Femininity, and Identity.

In 2016, shortly before the book went to print, Beal and Clark branched their ministry into YouTube, creating a channel that now has more than 150,000 subscribers, and began preparing for their first conference. It would be a space where girls could come and listen to the testimonies of older women, at once building friendships with other attendees who shared similar views on how best to serve Christ.

This year, in main stage sermons, Beal and Clark preached the importance of submission in a world that has fetishized women’s independence and self-sufficiency. Bri Clark, Kristen’s sister-in-law, advised girls to layer t-shirts under dresses and order skirts in tall sizes to combine modesty and fashion. Jasmine Jacob, a one-time attendee, led a breakout session where she suggested pouring oneself into devotional life to bide time in “seasons of singleness.”

In earlier years, girls in attendance may have introduced themselves to those they stood next to at worship performances or ran into in the common areas of nearby hotels. Now they were left to socialize in the comment section, a place filled with praise for the sisters and gratitude for a community that welcomes scriptural interpretations of womanhood.

Jayla Scott, a 19-year-old from Fairfield, Illinois, told me she found Girl Defined through their videos on keeping a “servant’s heart” in marriage. As a senior in high school, Scott became engaged to her boyfriend of six years, and they married this past July.

“People focus on the sexual aspect of it, but it’s not just that,” Scott said of the transition from single woman to wife. “There are many other aspects than just physical.”

The conference introduced her to a number of like-minded Christian women from different parts of the country whom she messages every day and considers some of her first female friends. It was an experience she called “life-changing.”

“These women follow God with their whole hearts,” Scott said. “They uplifted each other and encouraged each other. It wasn’t a competition, we were united.”

Here, it is easy to forget that to most people, Beal and Clark are wildly unpopular internet characters. In 2018, YouTube comedians Cody Ko and Noel Miller posted their first of two videos mocking the Girl Defined channel, zeroing in on Beal and Clark’s expectations for godly men and biblical advice for “guy-obsessed” girls. The video hit more than 20 million views and brought the sisters’ relatively unknown platform to the fore of the online zeitgeist. Now it is difficult to sort out how much of Girl Defined’s following subscribe to their religious views and how many come to try their own hand at comedy.

In the comment section of every public video, viewers throw shots at the sisters’ looks and speculate on their sexual performance. Some state as fact that Beal’s husband is a closeted gay man who went to conversion therapy, referring to a legless conspiracy theory born out of a 2019 “Dear Mr. Atheist” video and repeated on Ko and Miller’s podcast. (Jimmy Snow, the online commentator behind the “Mr. Atheist” alias, apologized for advancing unsubstantiated claims a week later, but by then the rumor had stuck.)

Ahead of the conference, Beal agreed to an interview with me, which she began with a procedural set of her own questions. “People have a lot of opinions and a lot of things to say about our ministry online,” she explained. She wanted to know if that is what this article would be about. I told her my interest is in the relationship evangelical girls have with online content creators and the way Girl Defined has been able to effectively build a young coalition against these antagonisms, to which she nodded and agreed that it’s a topic worth exploring.

In our conversation, Beal was reluctant to suggest that any of the ridicule they experience is gender-based, even when the comments are at their most degrading. She spoke fast, in long, roundabout sentences, pausing only to adjust the six-month-old baby tucked into her elbow.

“We don’t come up with our content out of the blue. We listen to what girls are asking and try to create content that best serves the majority.”

Her main theory is that it’s a combination of strong personality traits and counter-cultural ideas that make the pair such an appealing target. But after an aside on the general brutality of internet trolls, she grants the public might not get the same “thrill” from anatomizing a pair of outspoken evangelical brothers.

The Christian girls of Gen Z are as online as any of their peers. Those who follow Girl Defined closely enough to invest in their conference—the “sisterhood”—see the jabs and know to be fiercely protective of Beal and Clark. The negativity surrounding them only confirms their suspicion that, yes, the world has become hostile to the word of God.

For the evangelical women in attendance, the internet has long felt like a source of constant othering. TikTok and Snapchat ask them to compromise their values in sexualized trends, and platforms like YouTube see their devotion as a joke. That isn’t an accident, one girl told me: it’s the devil working. Girl Defined takes on a big sister role, offering ultra-specific advice for these novel problems, usually framed in binary questions: should Christian girls use TikTok? (Short answer, probably not.)

“We live in a culture where our view on sexuality is so skewed,” said Alyssa Stephens, a 21-year-old freelance marketing consultant who has attended the conference for the past four years. “It is condemned as a sign of weakness to embrace your calling as a woman of God.”

Stephens lives in Paris, Texas, a day’s drive from San Antonio, and kept the hotel reservation she booked for the conference months ago, using the virtual pivot as a way to indulge in a getaway weekend. She likens Beal and Clark’s ministry to the story of Jesus and the woman at the well in the Book of John—rather than waiting passively for the world to accept salvation, Jesus met with someone who did not accept His truth, speaking in terms she would understand and reaching her through common ground.

“We’re not lacking in a mission field,” Stephens said. “We just have to meet people where they are, exactly how Jesus did.”

Emmy Spelman, an 18-year-old from New Jersey, agreed that her generation has fallen prey to lax views on physical intimacy. Since discovering Girl Defined, she has reevaluated her commitment to purity, now choosing to abstain from kissing until her wedding day as Beal and Clark did. Even in Christian circles, it can be a lonely promise.

“I face a lot of judgment from people that are close to me and I need to remember the motivation behind it,” said Spelman, who started her first year at Liberty University a few weeks ago. “They inspire me to stand firm in the midst of that and to continue being open with people, not to hide my faith or pretend to be something that I’m not.”

It can be tempting to write off this type of worldly defensiveness as the paranoia of privilege; Evangelical Protestants remain the largest religious group in the United States. But in recent years, the fire has burned from within—flocks of women have spoken publicly about the lasting trauma of fear-based abstinence teachings and expressed resentment towards being reduced to their sexual behavior inside the church. Rhetoric that falls under this umbrella was given a name: “purity culture.”

In 2016, author Joshua Harris called his fabulously popular abstinence memoir I Kissed Dating Goodbye a “mistake,” apologized for its 20 year legacy and announced he was no longer a Christian. That same year, writers and activists used the hashtag #KissShameBye on Twitter to denounce ritual paraphernalia like purity rings and True Love Waits pledges.

Beal does not associate Girl Defined with the evangelical ministry of decades past. She argues that it is possible to celebrate God’s design for purity and not engage with the toxicity of purity culture.

“It’s so important to emphasize that sex is a good, beautiful, wonderful thing,” she said. “I wish I could shout it from the rooftops: our choices on whether or not to save sex really have nothing to do with our value. Yes, God has a design for that, but God loves us in spite of everything we choose to do.”

While Beal’s statement shares the progressive language of some of Girl Defined’s critics, there are two different interpretations of freedom at play. As with all sin, falling short of the model of purity—physical, emotional and spiritual—is seen as almost inevitable. That does not change the fact that it is the model. The ultimate sexual freedom, in the ministry of Girl Defined, comes when one acknowledges this losing battle and chooses to pursue abstinence anyways.

In conversation, Beal speaks of a secular world that has failed young women in its permissiveness. She wants more for the girls struggling with anxiety and eating disorders, girls who she says participate in the “crazy cycle” of trying the same things and hoping for better results. She has seen biblical womanhood transform her life and the lives of those around her. She believes it can work for others, too.

But proselytization isn’t the goal at the conference. Unlike the public ministry, Beal and Clark are not trying to convince an unfriendly audience that they should reserve kissing for marriage or pray to break free from the sin of masturbation. Those watching have paid to be here. It is reasonable to assume they all agree.

On Saturday evening, after the conference closed with a group prayer, the Facebook group flooded with posts from attendees vowing to stay in touch and continue together in spiritual growth. From her parents’ home in the rural Midwest, Audrey (a pseudonym), added her own contribution: “Just wanted to say, if any of you are LGBTQ+, Jesus loves you! And I’m so sorry if anyone (especially in the church) has made you feel otherwise.”

She received one response: “Yes, but Christ is enough,” with a heart emoji. The responder followed up with a reading list, each relating in some way to the sin of lust: Sam Allberry’s Why does God care who I sleep with?, Rosaria Butterfield’s The Secret Thoughts of an Unlikely Convert and Jackie Hill-Perry’s Gay Girl, Good God. Audrey was loosely familiar with the last title, a memoir from a woman who describes her same-sex attraction as a product of original sin, a struggle she was able to overcome through salvation.

Before Audrey had the chance to respond, she received a notification that an administrator had deleted her post. “I cried,” Audrey said. “I called one of my best friends and I cried when I saw that.”

The post was not meant to be controversial. She figured it was a numbers game—if 800 girls attended the conference, at least some would have experienced same-sex attraction. For them, the message was a plea to stay in the church. She now worries the deletion netted the opposite result.

“I didn’t want to start a debate,” Audrey said. “I just wanted to repeat Jesus loves you.”

Girl Defined did not address same-sex relationships by name at any point in the two-day conference, and it is rarely brought up in the ministry. There are other issues the sisters avoid as well: political behavior, scientific dissent, denominational identity. An early blog post on showing compassion towards prostitutes, homosexuals and Muslims in spite of their “brokenness” was deleted from the site, and their first and only video addressing race or racial injustice was released in June.

This shift away from discussing issues outside the bounds of “godly” relationships may have been a product of the sisters’ sharpened awareness of their target audience over time: “We want to focus on the things we best understand,” Beal said, although she did not refer directly to posts that have been deleted. “We don’t come up with our content out of the blue. We listen to what girls are asking and try to create content that best serves the majority.”

When I asked Beal if it bothers her that silence on these topics could lead to new viewers drawing their own conclusions on where the ministry stands, she said that it’s “not really a concern.”

Heather White, a professor at the University of Puget Sound who specializes in the history of sexuality and religion, explained that these are lines that are drawn, blurred, and redrawn in every generation of evangelicalism. They remember similar tensions at Young Life 20 years ago. Among highly religious peers, teenagers were encouraged to block out the noise of culture and look inward to search for their identity within God. Some of those teenagers looked inward and found they were gay, which was not the kind of introspection ministry staffers intended.

“It may be that there is a tipping point we’re reaching,” White said. “But it does make me wonder, is that tipping point going to be clear and decisive? There’s a piece of that openness and shut-down response that just keeps on happening.”

After experiences of hostility in ministries that claim to offer unconditional belonging, there is usually a crossroads for queer evangelicals: a compartmentalization of identity or a dissociation from the church. For those who maintain a belief in modesty, purity and other traditional social mores common in evangelical teachings, options for community become smaller, and they require even more compromises.

There are churches that actively and publicly affirm their LGBTQ+ members, should teenagers choose to wait it out and pursue a life of faith in adulthood. But even if they are willing to abandon denominational ties and have the means to move to a place where these churches exist, there can be a crisis of authenticity and a struggle to replicate that “evangelical feeling,” White tells me.

“It doesn’t feel like Christianity in the same type of way,” White said. “You sometimes feel like it’s not real spiritually.”

Both Beal and Clark declined to respond to multiple requests for comment on the removal of Audrey’s post specifically. But in our conversation, Beal was careful to argue that the ministry’s focus on sexual discipline was a strategic decision, and one born out of compassion. While it’s common in evangelical spaces for men to have support groups to openly discuss pornography and unwanted desire, women and girls are usually left to suffer in silence. Opening this dialogue was not meant to suggest that sexuality is, or should be, the basis of a young woman’s faith.

And for the young women who attended the conference, this seemed to resonate. Even under Girl Defined’s branding, abstinence was far from the most popular topic of discussion in the Facebook group.

Through October, posts and responses continued to appear on the page. There were prayer requests for healing through grief, illness and a bevy of personal tragedies. There were confessions of anxiety about the rapture and what it might be like to be torn from friends and family without warning. A few girls went back and forth on how they imagine heaven.

These are conversations that Audrey, and almost certainly other women of devout faith, want to have. But the sisterhood is splintered within its own otherness. There are terms of entry, even for those who share Girl Defined’s vision of a Christian life. In a generation that is significantly less religious than any before, the places where these women can turn for a young and comparably observant community are few and far between.

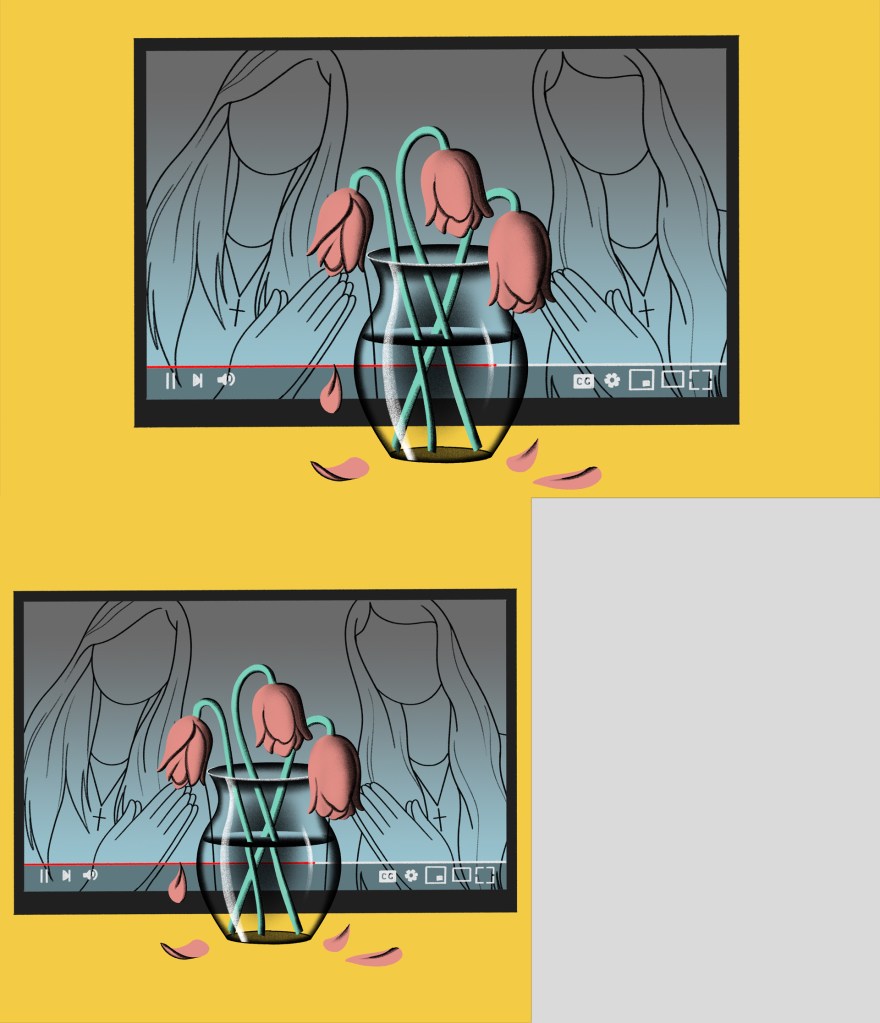

In the last session of the conference, Beal and Clark brought a flowering potted plant onstage. At first, the pair made a show of admiring its beauty and growth, only to cut each flower by the stem, removing them from the soil and placing the blooms in a glass of water.

“We all know what happens over time,” Clark said. “These flowers might look good right now, but what’s going to happen a week from now? These flowers will be wilted, the petals will be coming off and they won’t be thriving anymore.”

If the flower as the emblem of religious purity was unfamiliar to any of the girls in attendance, it would likely be familiar to their mothers. Here, just as in the posies sketched on the covers of women’s devotionals for generations, there is no removing virtue from femininity, and no removing femininity from faithfulness.

Clark went on to analogize the separation of the flowers from the soil to the separation of the soul from Christ. As an audience, we were meant to be distracted by their short-lived beauty, goaded into mistaking it for liberation. It wasn’t our fault—the temporary pleasures of the world are attractive by design. The best we are asked to do is approach with caution and the comfort of a similarly yoked cohort. “You have been adopted as His daughter into His family,” the sisters said, eyes closed, hands to God.

Follow Scout Brobst on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

AstroForge/SpaceX -

Juan Moyano/Getty Images -

Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic/Getty Images -

Screenshot: 2K