“There was a guitar convention in this hotel where each room was dedicated to a different manufacturer,” explains Robert Trujillo, the Metallica bassist who is painting a personal experience from the 80s to me, with all the excitement of a hysterical child. “Suddenly this huge loud noise started filling the building, so loud the windows were shaking. I walked into a room and Jaco was just sitting there, playing the bass. I was too nervous to actually say anything to him so I just sat down in front of him to listen. Before long the whole room had filled up. I remember him looking around the room, eyeing everybody up, as if to say ‘Yeah, I’m the man!’” Trujillo hung on his words, silent for a second, palpably recalling the unparalleled significance of seeing Jaco Pastorius in person. “Then after a while his girlfriend Teresa came into the room and said they had to go. He mumbled ‘ok’, propped up his bass and walked out.”

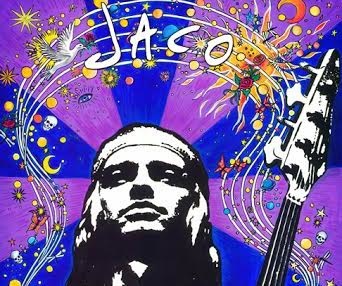

In a few weeks time at SXSW Festival, a documentary will screen that explores the almost mythical story of Jaco Pastorius, an electric bass pioneer – an invisible icon who was an enduring inspiration for artists like Trujillo, but also Herbie Hancock, Joni Mitchell, Flea, Bootsy Collins and so many more.

Videos by VICE

If you already know his name you are probably either also a bass player, or the type of muso that hangs framed vinyls in place of family photos. Every generation has musicians like him, categorically changing the game but never really having their legend realised in the moment, and the documentary will be another addition to the canon of projects that attempt to attribute long deserved recognition to these sorts of figures. Be it Nigerian funk artist William Onyeabor, or 2012’s academy award winning ‘Searching For Sugarman’, the cinematic scope in trailing the fates of nearly-superstars is clear. We want to know where these pioneers dropped off, and, more importantly, why?

Born in 1951 and growing up in Florida, Jaco began his musical career playing the drums, before a wrist injury forced him to try another instrument – the bass guitar. The rest has become pure folklore. As a composer he went on to stretch the potential of the bass like a steel-thumbed sorcerer pulling on the very fabric of time; experimenting with harmonics and fretless improvisation in such a way that managed to be both highly technical and totally funky all at once. But he met his maker far too soon, on one bad night in 1987, and his story was left largely untold.

For Trujillo, who is the documentary’s producer, his involvement in portraying Jaco’s life is an obligation to an artist that not only inspired his craft, but negotiated his entire creative perspective. “I’ve been good friends with Jaco’s son Johnny for many years, and I’ve always been saying, ‘You have to make a documentary, you have to tell his story.’ After years of this, he eventually asked me, ‘Well do you want to be involved?’”

The legend of Jaco informed Trujillo’s entire education in music. “In my younger years I could go and see shows at a venue 5 minutes away from my father’s house. I saw Jaco then and I’ve never forgotten what an amazing live performer he was. He played jazz mostly, but even people like Zack Wylde, who played guitar for Ozzy Osbourne, cite Jaco as an influence on his performance. It was the attitude.”

The brief career of Jaco Pastorius is built on stories like this. Encounters and jams characterised by his in-built skill for dominating a room. The documentary features a host of musicians from all genres and corners who cite him as an inspiration. All of them speak of an artist who changed the game, with Collins going as far as to say: “Before Jaco, bass didn’t know what it was.”

Trujillo is keen to remind me though, that the love these musicians have for the bassist goes way beyond the instrument. “Everybody spoke about Jaco as if he was their friend. Not just a musical influence but someone they were close to.” For Pastorius as well, it seems his connections and collaborations meant more than high profile feature credits. “This is someone who worked with Joni Mitchell without really knowing who she was. They just met and had a connection, so made some beautiful music.”

Tragically, unlike the stories of William Onyeabor or Sixto Rodriguez, Jaco Pastorius is no longer around to enjoy the intense appreciation the roster of names featured in the film feel towards him. Despite staying sober for many years, in the late 1970s he began drinking and using cocaine, the start of a slope that eventually led to his mental decline. In 1987 he attempted to kick down the back door of a bar called the Midnight Bottle Club after being ejected from the venue. Upon discovery, the bar manager beat him, fracturing his skull and ultimately ending his life.

Trujillo considers the incident a true injustice, “He wasn’t with us for as long as he should have been.” It is clear from his words, and those of the film’s other contributors that the death should not be seen as the inevitable result of hedonism but rather as a consequence of mental illness in an environment that failed to recognise it. In a piece for the Jaco Pastorius website, the bassist’s daughter has written: “If you are living in the throes of manic-depressive illness, your mistakes are going to be on a much grander scale and with far greater consequences.” It is a sentiment echoed by Trujillo, who somberly comments, “if you are suffering from mental health issues even a little bit of the party lifestyle can push you over the edge.”

It is perhaps because of his decline and death that Pastorius has never been celebrated in the appropriate way. He hasn’t been around to collect hyperbolic legacy awards, be consulted by Kanye, or to appear on a Daft Punk album. Moreover, because his career slid off-piste before his death, he didn’t die at his peak in the same way as John Lennon, Ian Curtis or Janis Joplin. Rather, as interest in his output waned, paired with his erratic behaviour, his death was written off as the messy conclusion to an almost brilliant life.

It says a lot about how we narrativise the lives of musicians, throwing nuance out of the window in favour of a rock n’ roll story that plays on drugs and booze driving geniuses over the edge. Trujillo certainly appreciates this misconception as essential to how he is telling the story. “The film is as much about the musician as it is someone’s struggle with manic depression. It has given me a huge amount of empathy and understanding, to the point where now, if I see a homeless person I see this whole story that could have led to that point.”

I thought it was worth asking Robert where a newcomer to Jaco should start, and before long he was rifling through his record collection agonising over what to suggest. “Well, the one that hit me first was the Weather Report song “Teen Town”. Oh, okay, one of the funkiest songs ever – and I mean EVER – is a song called “Come On Come Over” (below). That will open your eyes, I mean Jaco could have made a full album of vocal R&B music if he hadn’t wanted to.” Within seconds though, he is backtracking. “It’s so hard though, I know people will be yelling ‘What about “Continuum”?’”

With the film heading off to Texas for SXSW, the Metallica bassist is preparing to show it to people for the first time after a trying gestation period. “This project has been about 5 years, in the trenches, trying to make it happen. At the start I had the money but it has ended up costing a lot more than anticipated.” Fitting though, for a documentary about a man who inspired so many people, Trujillo hasn’t been alone. “Many people love documentary films, but they don’t understand how much time and money they require. Without my director of photography Roger De Giacomi, Jaco’s son Johnny Pastorius, the bassist Jerry Jemmott this couldn’t have happened. Of course I owe the most to my director Paul Marchand – that’s his artistic statement on the screen.”

The pride with which Trujillo gushes name after name speaks of the family that have pulled together to make the project happen, a family drawn together by their unbreakable devotion to a musician and person who changed their lives. Robert Trujillo’s hope now is that with his film, the family will grow even bigger. “I don’t think being a bass player has anything to do with why I’m trying to bring this story to the world. It should motivate people who want to be artists, be that musicians, filmmakers, or writers. Even if you don’t want to be an artist, it will just inspire people who want to discover really great music. Jaco loved all styles: jazz, country, rock, gospel. That’s really one of the messages in the film… music is for everybody.”

You can follow Angus on Twitter.

Learn more about Jaco: A Documentary Film here.

More

From VICE

-

Photo by Neil Lupin/Redferns -

Eva Pascoe, founder of Cyberia, poses at the cyber cafe in London. All photos courtesy of Eva Pascoe, Ali Knapp, and Roger Green. -