Somewhere deep in the polluted heart of Los Angeles—maybe East LA or Boyle Heights or South Central—there’s probably a backyard punk show going off right now. At first, it might look like any other punk gig: Kids with mohawks, dye jobs, and spiked collars moshing, drinking, and having a good time. But look a little closer and you might notice that the drummer is sitting on a lawn chair, not a drum stool. There’s no mic stand, so the singer/guitarist’s buddy is holding the mic for him. Oh, and pretty much everyone here is brown: These are Latino punks with their own scene, their own bands, and no need or desire for attention from the mainstream—or even, sometimes, the wider punk community. Before long, a police helicopter circles overhead, its spotlight strafing the crowd. Then the ground troops move in: LAPD’s boys-and-girls in blue run crowd control and dispersion tactics. Maybe they’re polite about it; maybe they’re not. You just never know how the night will end.

Filmmaker Angela Boatwright captured all of this and more in her new documentary, Los Punks, which will make its New York premiere on May 26 and become available on iTunes the following day. After spending years as a NYC-based photographer working with metal bands and skateboarders, Boatwright moved to LA in 2012 and went to her first backyard punk show the following year. She initially started filming the punks for short video webisodes sponsored by Vans. Before long, she found herself making a feature-length documentary with financial support from the famous footwear company. “It’s a self-sustaining scene,” she says of the previously hidden culture she spent three years shooting. “At the shows, you might see a Bad Religion or a Black Flag shirt here and there, but for the most part people are wearing the shirts and patches of the backyard bands. They support each other. It all goes back to family and community.”

Videos by VICE

Noisey: How did you end up at your first backyard show?

Angela Boatwright: I moved to Los Angeles in 2012, and I was trying to find some like-minded people to hang out with. Through a couple of people, I heard about backyard shows in East LA. The first show I went to, I was going to scout for people for the webisodes. My friend Ron Martinez invited me to see his band Lower Class Brats play in the Valley, and that’s when I saw all the kids at the shows and it was like, “Holy shit—what’s going on here?” That’s when Vans asked me to pitch them a [movie] idea, so it all happened at once.

You’ve been going to underground shows for a long time. What about these particular shows stood out to you—other than the fact that they happen in backyards and are populated almost entirely by Latinos?

It felt like I crawled into another dimension, like I time-travelled. And that’s exactly the kind of adventure that I love. To get to the heart of it, it felt secret. And if you think about it that way, I’m the enemy because I’m the one bringing the secret to the public. But I personally feel like the backyard scene is so special and so distinct that even a movie like Los Punks isn’t going to eliminate it. I think it can maintain its anonymity regardless of the movie. That’s my hope, at least.

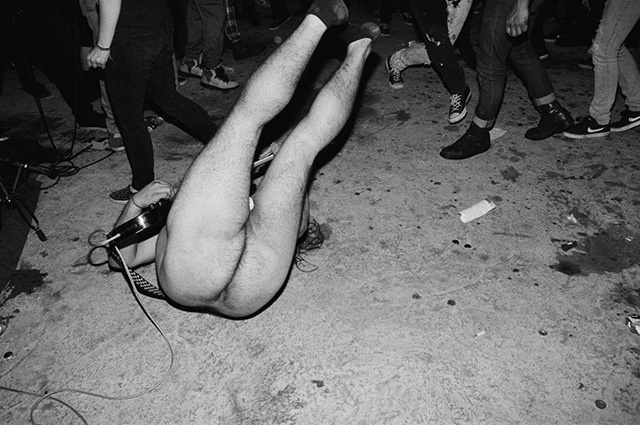

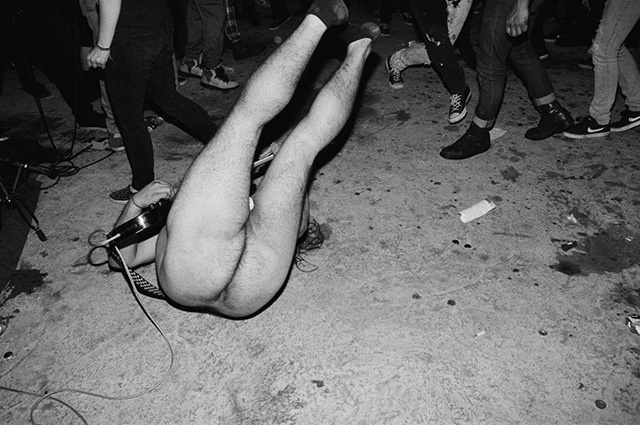

Eighteen year old Nathan in the mosh pit, South Central, October 13, 2014.

When you started filming, did you get the sense that some of the punks didn’t want you there exposing their scene?

Yes, and some of them still have that feeling. But I worked a lot with skateboarders in New York, who can be very fussy, especially because I’m a girl who doesn’t skateboard. They don’t care if you’re cute, or whatever—if you’re not born and raised in New York, get the fuck out of here. I was also picked on all four years of high school, so I’m used to people not wanting me in their scene. It’s a consistent pattern in my life that people don’t want me around. My parents didn’t want me around. People in high school didn’t want me around; people in New York didn’t want me around. So fast forward to being 40 years old, and it’s like, “Try me, dude.”

How did you deal with punks who didn’t want you at the shows?

I stayed. Some of them warmed up to me, but there were some punks who were really excited about me being there at first who actually backed away. And then there were some who didn’t want me there at all who love me now.

The Casualties play a backyard in South Central, July 20, 2015.

The Casualties play a backyard in South Central, July 20, 2015.

Kat from Las Cochinas performs at the Euclid House, Boyle Heights, August 17, 2013.

Kat from Las Cochinas performs at the Euclid House, Boyle Heights, August 17, 2013.

Now that it’s being released, is the film still getting resistance from punks within the scene?

No, but the webisodes got a lot of hate because it was just like shining a mirror onto their scene. An example is something as simple as going into the mosh pit and you feel like king of the world, like a badass, and you’re pushing people around, but then you see yourself in the movie and it’s not like that at all. So it’s hard. The hate ripped through the scene—it was bad—but I kept going to shows. The punks saw that, so I worked on people one at a time.

But I’m not a director who’s like, “I’m gonna find the most valuable thing to direct that’s gonna make me famous.” I don’t really care about that. I could just teach, you know? My motivations are to help people, to get into young people’s lives and change them. If directing a documentary is the vehicle to do that, great. If becoming a teacher is that vehicle, that’s fine, too.

Seclorum play in a parking lot, South Central, August 1, 2014.

Seclorum play in a parking lot, South Central, August 1, 2014.

Were you confronted by anyone at the shows?

Yeah, all the time. Our crew was not very big—sometimes I was the only one there. At the show [in the film] where the cops show up and accuse someone of stabbing a person, I was the only person there. But the biggest crew we had would’ve been maybe ten people max, including security.

Did you feel like you needed security?

When you do a production like this, there are legalities involved. If you hire a security guard and your stuff gets stolen, they’re more likely to replace it because you did your due diligence. But we would always hire people of color and we always made sure they showed up in plain clothes. A lot of times I’d end up hanging out with them or they’d end up hanging out with the punks. In a couple of cases, the security were people who used to go to punk shows. But for the record, nothing ever happened to our camera crew.

Crusty Drunks perform in a parking lot, South Central, August 1, 2014.

Crusty Drunks perform in a parking lot, South Central, August 1, 2014.

The police shut down these shows fairly often. How did that affect the filming?

Oh, I love that stuff. The very first show I went to got raided by the cops. The police are 50/50, you know? Sometimes they’re shitty and sometimes they’re cool. Sometimes they’re cool to me and not cool to the punks—that was really common. If anyone believes that white privilege is not a thing, I can tell you it absolutely is in this city. I have a lot of examples. But I’d have long conversations with police officers after they raided shows—even along with the some of the punks. I like that stuff. I don’t like it if people get hurt, though.

Were you nervous about the police presence at all? When cops interact with young people of color these days, there’s a very real possibility that a kid could end up dead.

Not when a white girl with a camera is there. By me being there, I change the situation entirely. I hope everyone knows that legally you can film police officers in the United States of America. In Los Angeles, all cops know that all citizens know that. So what they’ll do is go, “You gotta stop using your flash. It’s blinding me.” Of course, all this stuff is happening at night, so it’s like, “You can take pictures, but don’t use your flash.” Sometimes I listened, and sometimes I didn’t. I definitely don’t want to go to jail, and I don’t want to get the punks in trouble, so I’d generally stop using my flash if they asked me. But another police tactic is that they’ll shine their flashlights at the camera. There was one night when two police officers raided a show in Huntington Park, and one of them just stuck to me the whole time, shining his flashlight into my camera. [Laughs] So I have all these photos of him. I call him “Officer Flashlight.”

In those situations—with both the police and confrontational punks—do you think being a woman was an advantage?

Big time. I don’t think a man could’ve done this movie, if only because men ego-trip each other. A guy coming into the scene with all these strong, capable male punks who have been there for years? No way.

LAPD raid a show in South Central, August 1, 2014.

LAPD raid a show in South Central, August 1, 2014.

There’s obviously a long history of DIY in punk music, and many of the punks in the film seem to adhere closely to its tenets. They like being self-created and self-contained and they’re not interested in the mainstream or maybe even the wider punk audience. But there’s a scene in the film in which the backyard band Corrupted Youth open for hugely popular punk veterans the Casualties at a real venue, and Corrupted Youth are understandably excited about the opportunity. What’s your take on that?

You know just as well as I do that there’s a big conflict in the scene about wanting to be successful. I personally have never had a problem aligning with sponsors. If someone wants to support something positive, I think that’s a good cause. But that’s just me. As human beings, you want to achieve success, but you also want to have a core group, a community of people you share your life and ideals with. [By appealing to a wider audience], you can risk losing your group, and for some people that risk is too big to take. So unfortunately some people choose not to move forward with their music for fear of losing their group of friends. But I’ve never really been like that.

On that note, do you think Vans’ involvement in Los Punks affects the conversation about your film to some extent?

Yes, absolutely. In an ideal world, it would’ve been great to do the movie on my own. However, the idea to do the movie materialized through my partnership with Vans. And they’ve been more than supportive. Vans didn’t say one thing to me during the making of this movie. They didn’t say, “We need to see more shoes” or anything like that. They aligned me with a really talented writer and producer, and they let me do my thing. I could’ve said, “No, I will not take money from a corporation to do a film,” or I could say yes and attempt to give a few people some opportunities. That’s what I did.

Crowd at a show in Boyle Heights. August 17, 2013.

Crowd at a show in Boyle Heights. August 17, 2013.

In the end, what do you feel like you accomplished with Los Punks?

I don’t know yet. But at the bottom of it, there’s no music industry anymore. The audience is so much smaller, so these scenes need our support. Bands don’t make the kind of money people think they do. If we don’t support heavy metal and punk, it will go away. So if I can deliver underground music to people in a vehicle they can enjoy, perfect.

Ray from Pleasure Wound, South Central, October 24, 2014.

Ray from Pleasure Wound, South Central, October 24, 2014.

Los Punks will have its NYC premiere at the House Of Vans in Brooklyn on May 26 with performances by the Casualties, South Central Riot Squad, and Age Of Fear.

Nitehawk Cinema in Williamsburg is hosting a special one-night-only screening of Los Punks on May 31. Director Angela Boatwright will be on hand for a Q&A with Cromag’s John Joseph following the film.

More

From VICE

-

Photo by Michel Linssen/Redferns -

Ron Levine / Getty Images -

Schulte Productions / Getty Images -

MacBook Air M1 — Credit: NguyenDucQuang for iStock Editorial/Getty Images