TEXT AND INTERVIEWS BY BERNARDO LOYOLA

PHOTOS BY ABELARDO MARTÍN

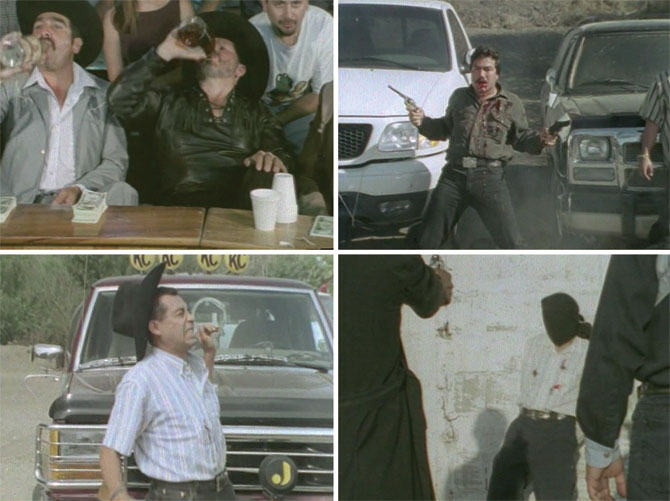

Dos carteles (2000), starring Mario Almada

Dos carteles (2000), starring Mario Almada

During the last few years, Mexican directors have received unprecedented international recognition. Movies like Babel, Amores perros, Silent Light, Y tu mamá también, and Pan’s Labyrinth have won awards at film festivals all over the world. Actors like Gael García Bernal and Diego Luna have drawn attention to a new generation of Mexican thespians. Hooray for them. But can we get some Mexican movies that aren’t all arty and heavy and full of good acting and clever directing? Why isn’t there a Mexican film scene that cranks out movies for the lady making tacos by the side of the road in Juárez instead of for the intellectual guy who teaches film studies in Mexico City? Aren’t the poor and working classes of Mexico clamoring for films that they can relate to?

Well, I guess you aren’t Mexican like I am. If you were you wouldn’t have asked those dumb questions that I just put into your mouth because you’d know about the magic world of Mexican narco cinema. Come on, I’ll tell you all about it.

For over 40 years, a hugely active B-movie industry has been producing super-low-budget films about drug dealers, bad cops, corrupt politicians, trucks, and prostitutes, catering mostly to the blue collar back home and the millions of Mexicans living in the US. In Mexico, this industry is called “videohome” because the movies go straight to video. If you go to a video-rental place in East LA, you’ll find one copy of Amores perros, but it will be surrounded by hundreds of other movies like Sinaloa, Land of Men; A Violent Man; The Dead Squad,; Her Price Was Just a Few Dollars; Coca Inc.; I Got Screwed by the Gringos; Weapons, Robbery, and Death; and Robbery in Tijuana.

This industry is frowned upon by embarrassed and ashamed middle- and upper-class Mexicans, and many people we tried to interview about it felt offended by the fact that we were even interested in narco cinema. A movie like Chrysler 300 sold thousands and thousands of DVDs last year, but many people in the trendy neighborhoods of Mexico City have never heard of it even though it was playing on every TV in the working-class areas. As Hugo Villa, a former official at the Mexican Institute of Cinematography, told us, “This is not a surprise when you realize that only 18 percent of the population in Mexico can afford to go to see movies in the theaters.” The reality is that videohomes are a far truer reflection of the tastes of Mexico than the kind of stuff that makes Frenchmen pee champagne into their tux pants at Cannes.

These low-budget action flicks are often based on violent stories from local newspapers. They can be written, produced, and released mere weeks after the stories are published. They are also often based on myths and legends about the all-mighty drug cartels from the northwest region of Mexico and stories about Mexicans crossing the border. Also, hilariously, tons of narcocinema movies revolve around cars or trucks. In any store that carries videohomes, you can easily find movies like The Black Hummer, The White Ram, The Red Durango, and two of the most famous classics of the genre, The Gray Truck and The Band of the Red Car.

In the mainstream Mexican film industry, it is rare to find a movie that eventually gets a sequel. There’s no Y tu mamá también Part 2. But in the videohome industry, any successful movie will become a franchise, so you have Dos plebes 5, An Expensive Gift 4, Chrysler 300 Part 3, and so on. Most sequels are revenge stories based on the original movies.

A few decades ago, these movies used to be westerns or straight action movies, but over the last two decades, the focus has shifted to drug trafficking. Mexico is the number two producer of both marijuana and poppies in the Americas, the majority of meth that seeps into the States is being made in Mexico, and the whole country is basically a superhighway for US-bound cocaine. Drug trafficking is a $100-billion-a-year business, and about 30 percent of that is estimated to go into paying off the government and the police.

Today, the narco wars going on in Mexico are out of control. Every day on the news you hear about shootings, executions, beheadings, and corruption. But it’s not only the cartels that are at war with each other. The current government has tried to stop the cartels, effectively militarizing entire areas of the country. This has sparked even more violence. So we have the cartels fighting the government, the government fighting the cartels, the cartels fighting each other, brutal killings every single day, and a group of dedicated workhorse filmmakers turning the whole thing into video faster than you can say arriba.

We recently met and spoke with two of the biggest narcocinema men in Mexico. Here’s what they had to say.

Watch The Vice Guide to Narco Cinema on The Vice Guide To Everything tonight at 11/10 central on MTV.

Narcocinema actor Mario Almada

If there’s one person who represents this industry, it’s Mario Almada. He’s kind of like the John Wayne of Mexico—a total legend. He’s 86 years old and he’s still making movies. He actually holds the Guinness World Record for the living actor who’s appeared in the most movies. We visited him at his house in Cuernavaca.

Vice: Have you made any movies lately?

Mario Almada: I just came back from Dallas. I was shooting a video there.

How many movies have you made?

I’ve starred as the lead in well over 300 films shot on 35 mm. That’s just counting films shot on film. I’m not counting videohomes. I’ve probably acted in more than 1,000 of those.

Hence your winning the Guinness record.

That’s what I’ve been told, but I’ve never seen it.

What’s the difference between working in 35 mm and in videohomes?

It’s very different. The big movies are shot over months and videos are made in six days. That’s why I’ve managed to act in so many movies.

And do you usually play the good guy or the bad guy?

Usually I’m the hero: an avenger, a cop, a sergeant, a sheriff. I’ve played priests and pretty much everything else. Except for a gay guy. Not that. If I played that, it wouldn’t even be believable. My characters always fight against violence and against the drug traffickers. Always. The only time I played the role of a drug trafficker was in The Band of the Red Car.

Who watches your movies?

Mostly the working-class people, but very often I run into women from the super-rich neighborhood of Lomas de Chapultepec and they tell me, “Mr. Almada, I watched one of your movies on TV last night. They are great. Please keep making them.” But the main audience is the working class in Mexico, the US, and South and Central America.

Is it true that a lot of these movies are shot in the US?

We’ve shot a lot of great movies in Brownsville, Texas. The Band of the Red Car was shot between Brownsville and Matamoros, Mexico.

And is that because the millions of Mexicans living in the US are really the market for your movies?

People there really like Mexican songs, but they also like the stories about the border, about illegal immigrants, and about drug trafficking. Movies like The Death of the Jackal and The Revenge of the Jackal were huge hits. We also shot those in Brownsville.

You just mentioned Mexican songs. There’s a very close relationship between narcocorridos [drug ballads] and the videohome industry, right?

There are so many of these songs. There are lots of characters who have been very famous, like bandits and such, and eventually someone writes a corrido about them. And based on that corrido, a movie gets made. And they are always very successful, because they are based on a song that’s already well known. For example, The Band of the Red Car. That started as a corrido that was made famous by Los Tigres del Norte, one of the biggest bands in Mexico. It tells the story of four friends who get killed. They were carrying 100 kilos of coke in the tires of the car. The movie came out of that song. You can see it all in the movie. We take the tires apart and all that.

You made other movies based on songs by Los Tigres del Norte, right?

Well, there was that one in 1978, but yes, we also made The Golden Cage, The Gray Truck, and Three Times Wetback. In The Gray Truck I play the father of a young guy who’s a drug trafficker. I’m his father but I’m also a cop, and that’s the main conflict in the movie.

I love the lyrics of that song. “It was a gray truck, with California plates/The truck was tuned out/Pedro Marquez and his girlfriend had tons of dollars to buy drugs/Their destination was Acapulco, that was their plan/Enjoy their honeymoon and on their way back carry 100 kilos of the fine stuff/Back in Sinaloa, Pedro tells Inez/‘Someone is following us, you know what you have to do/Take out the machine gun and make them disappear.’” And in the end, they crash into a train and die. I love that movie too.

Yeah, it was a very beautiful movie. The Golden Cage was very good too. That’s about a guy who wants to go back to the US, but his family doesn’t want to go with him. In the end, he manages to cross the border and takes his family with him.

Now, I’ve heard that some of these movies are financed by…

By drug traffickers? Well, yes. It might be true. I’ve never looked into it. I have a lot of producer friends who wear gold chains and diamonds, but I don’t try to find out if they are drug traffickers or not, because they’re nice. They’re good people.

Have you ever met any big drug dealers? Any capos?

I met Rafael Caro Quintero in the 80s in Guadalajara. He invited us to his table at a restaurant and I had drinks with him. He was a very charming man, a very generous man who did a lot for his people. He built schools. We made Operation: Marijuana about the beginnings of Caro Quintero, when he had those plantations everywhere. He got into something illegal and he ended up in jail, but he was a good man.

What do you think of mainstream Mexican films being made today?

There are a lot of good movies being made today, but they are not for the majority of the people. They are made for an elite. There need to be films that everybody can watch, not like Y tu mamá también. That’s pornography! Filmmakers come out of school today with weird ideas. People don’t like those complicated themes that they make their movies about.

Will you continue making movies?

I will, long as my body allows me, but it might not be for too long. I’m 86. That’s too many years! I’ve seen so many things in my life!

Watch The Vice Guide to Narco Cinema on The Vice Guide To Everything tonight at 11/10 central on MTV.

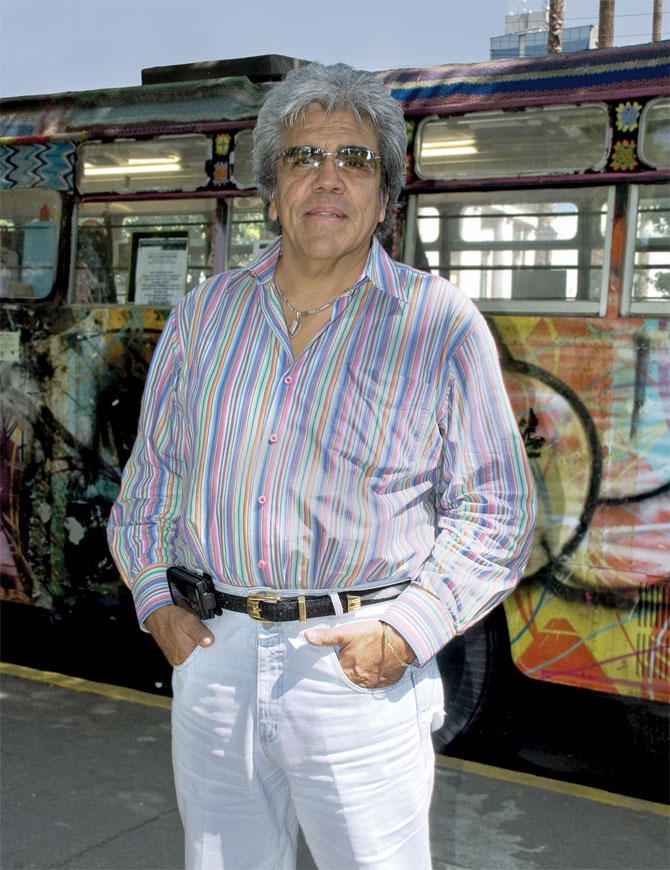

Narcocinema producer/actor/director Jorge Reynoso

We really wanted to talk to film entrepreneur, director, producer, and actor Jorge Reynoso. As opposed to Mario Almada, Jorge usually plays the most badass of bad guys. He was hard to pin down. He canceled on us a couple of times and when we finally met him in Mexico City while he was supervising the editing of his latest movie, he explained to us that he had been busy, traveling in Asia on someone’s yacht, visiting factories in China to start the production of his very own hot sauce: Rico, Picante y Sabroso, el Sabor de Jorge Reynoso [Good, Spicy and Delicious, the Flavor of Jorge Reynoso], which he plans to sell at Walmarts in the US next to the DVDs of his movies.

Vice: What’s the difference between making films and making videohomes?

Jorge Reynoso: It comes down to distribution. Theatrical films are shot in HD or 35 mm and then they are projected in theaters. Videohomes are shot in 16 mm, HD, or DVCAM and they go straight to video and are distributed in supermarkets or video stores.

So how much money and how much time does it actually take to make these movies?

The costs are between $40,000 and $50,000 for a well-made movie. We ask someone to write the script, which is done in three or four days. There are some great Mexican writers. So in a week and a half, I have the preproduction of the movie ready. After that, we have two weeks to shoot it. So in five weeks, the movie is already on the market. I’ve made as many as 26 movies in a year.

That’s incredible. What do you think of the Mexican film industry? What’s the difference between the mainstream Mexican films that are known internationally and the kind of movies that you make?

I think there are some great movies being made today, but I also think that they are made for people who can afford to watch them. They are not really films for the majority of the people, because the working class doesn’t have access to them. First, there are no movie theaters in the small towns and rural areas, and second, I think that the themes they talk about are a bit off from where they should be, in terms of culture and values. I think those movies are too risqué. I think they’ve gone too far, but they win awards and compete at the major film festivals. The kinds of movies we make are very different.

How so?

This style of action movie that we make today, based on news stories, about the mafia, was started by me, and I made them popular by working with the record labels and by including popular corridos in them. People actually know me as “The Lord of the Guns,” because I’ve killed lots of people… in my movies. Most of the movies I’ve made are about the mafia. These movies are very well received by the Mexicans living in the US, because they can relate to the characters in them, who are very respected, and loved by people that live in small towns, and also by the musical groups that sing corridos.

So you are saying that Mexicans celebrate their drug dealers?

What happens is that drug traffickers in Mexico come from the countryside. They are people who make their way out of poverty. Once they succeed, they do good things for their hometowns. They build schools and hospitals, they create jobs, and, obviously, people love them. There’s even a patron saint of the drug traffickers. His name is Jesús Malverde and his shrine is in Culiacán, Sinaloa. People go there and they leave candles and they sing songs for him. It’s a fascinating culture, and it’s the reality of Mexico.

Have you ever met any big drug dealers while making your movies?

I’ve had the opportunity to meet many of them. In fact, we’ve made some important movies with these people where they’ve worked with us. They’ve been with us, but obviously I was never a snitch and that’s why I’m still alive. I’ve never betrayed the trust of any of them, who always gave us and continue to give us their friendship. The first movie that I made about the mafia was called The Mafia Trembles, a movie made about Rafael Caro Quintero, who was a very important drug trafficker in Mexico. We made La Mafia 1, La Mafia 2, and La Mafia 3. They were highly successful.

Watch The Vice Guide to Narco Cinema on The Vice Guide To Everything tonight at 11/10 central on MTV.

La Hummer negra (2005), starring Jorge Reynoso

La Hummer negra (2005), starring Jorge Reynoso

Yeah, in the 80s he was one of the biggest drug dealers in the world. I remember that when they captured him in Costa Rica, he actually offered to pay off the foreign debt of the country if they let him go, and he said the same when he was extradited to Mexico.

Yeah, but I think he’s still in jail today.

Do the police ever come and ask you where you get the information to write your movies?

It has happened in the past. The State Department would call me to ask me if I knew where such and such person was hiding. I would answer them, “You should know where he is. You are the police, I’m just an actor.”

Did you start out making mafia movies, or were there other genres for you first?

In the beginning we started making movies about the illegal immigrants. More than making movies, we were making an homage to those people who make it to the “other side” despite all the difficulties. We feel very proud of them. Then we started making movies about the mafia. Although it was somewhat risky because the Mexican mafia is the second- or third-most powerful in the world, I continued making them, often based on narcocorridos. The record labels would approach us and give us songs, and we would make movies about the songs that were playing on the radio. We still do that today. People used to tell me that I looked like a mafioso and that I should play that kind of character, so that’s what I do, and I play those characters with a lot of pride and dignity.

It’s interesting that a lot of these movies are Mexican productions but are shot in the US. Why shoot there instead of Mexico?

We get a lot of support from the Mexicans who live there. People know us and they get very excited when they see us there. When you shoot in the places where they live, like Houston, Dallas, California, or Chicago, the people get very involved. Also, the mayors of many American towns are of Mexican origin, and they help us a lot.

Where do you sell the majority of your movies?

Our main market is the Mexicans living in the United States. Piracy was hitting us really hard, but we realized that if we sold lots of DVDs of our movies at supermarkets at very accessible prices we could make a profit. Walmart has more than 2,000 stores in the US. If we sell five copies at each store, we are talking about 10,000 copies, and they can be sold in just a few days. At Walmart they place our DVDs next to Mexican food products. For example, you can find a movie starring Jorge Reynoso next to some delicious enchiladas. We put four or five movies on a single DVD. We also sell our movies to TV stations in California, Texas, and Illinois. You give the people movies they want, with songs, with a beautiful actress, a handsome guy, and a killer, and they will buy them.

You’ve mentioned narcocorridos. It’s very interesting how this music has changed over the years.

Corridos were songs originally from the Mexican Revolution, originally from the beginning of the last century. They would make songs for the fighters and heroes like Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata or the women fighting with them on the front lines. In recent times, this kind of song is made for and about important characters of the Mexican cartels—dignifying them, and making them into larger-than-life heroes. People in the Mexican mafia love this kind of music.

A lot of these kind of movies are based on popular narcocorridos, but I know that in the past three years, there have been over 25 violent killings of musicians, like Valentín Elizalde and Sergio Gómez, attributed to the drug cartels, supposedly for singing in the wrong territory or about the wrong people. Do you ever get in trouble for making a movie based on the “wrong” song?

The song gives you the synopsis for the movie and, based on that, we make the adaptation. But of course, you have to ask for permission. You need to have good relations with these people so you don’t get in trouble. Because if you make changes to the story that they don’t like, then you will have some problems. God bless, we’ve always done things the way they should be done.

There are a lot of recurring stars in your movies, but it seems that non-actors play a lot of the characters too.

The scripts are written in such a way that everybody can participate. Like the strippers, who are always great with us. They are awesome girls. The security guards, the cops, the drunk guys, the hit men, and all the people who are in that kind of environment always work with us. What you see is what you get. The prostitute is a prostitute, the cop is a cop, and the drug dealer is a drug dealer.

Watch The Vice Guide to Narco Cinema on The Vice Guide To Everything tonight at 11/10 central on MTV.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Archive.Org -

(Photo via brightstars / Getty Images) -

(Photo via Lorado / Getty Images) -

Getty Images