The world’s largest mass suicide took place on November 18, 1978, inside an isolated compound in Jonestown, Guyana. There, more than 900 members of the Peoples Temple cult ingested a drink mixed with cyanide. The horrific event was orchestrated by Reverend Jim Jones, a charismatic and manipulative preacher from Indiana who gained prominence in the Bay Area.

Jones established the Peoples Temple in 1964 in Redwood Valley, California. He quickly gained a following that made him a powerful political force with connections to men like California governor Jerry Brown. From the outside, the church seemed to embody the spirit of the 60s, extolling socialism and championing black radicals like Huey Newton. They offered free services like food for the indigent. And they had a diverse congregation. But behind closed doors, Jones manipulated his followers into giving the church all of their assets. He ruled over them with humiliation, coercion, and physical abuse. Paranoid that the media and lawmakers would expose the brutal side of the Peoples Temple, Jones moved the church to Guyana, where he claimed he would establish a socialist utopia. Instead, he led his followers to slaughter in the name of “revolutionary suicide.”

Videos by VICE

Deborah Layton is one of the few people who followed Jones down to Guyana and survived. While she suffered from the abusive tactics of Peoples Temple, she plotted her escape, which involved subterfuge of Jones’s armed followers and procuring a new passport. She fled by plane on May 12, 1978, leaving behind her brother and her mother who would eventually die of cancer in the camp. Back in the US, she testified before the State Department, warning of the potential for mass suicide. Unfortunately, she was too late. Inspired by her address to the State Department, Congressman Representative Leo Ryan (a Democrat from California) led a fact-finding mission on November 15 to investigate the religious settlement. On November 18, the politician and several others were murdered by Peoples Temple followers when they tried to leave Guayana—Layton’s brother, Larry, was arrested and later convicted for his role in the killings. That same day, Jones ordered the mass suicide—those who didn’t drink the poison willingly were stabbed with syringes of cyanide.

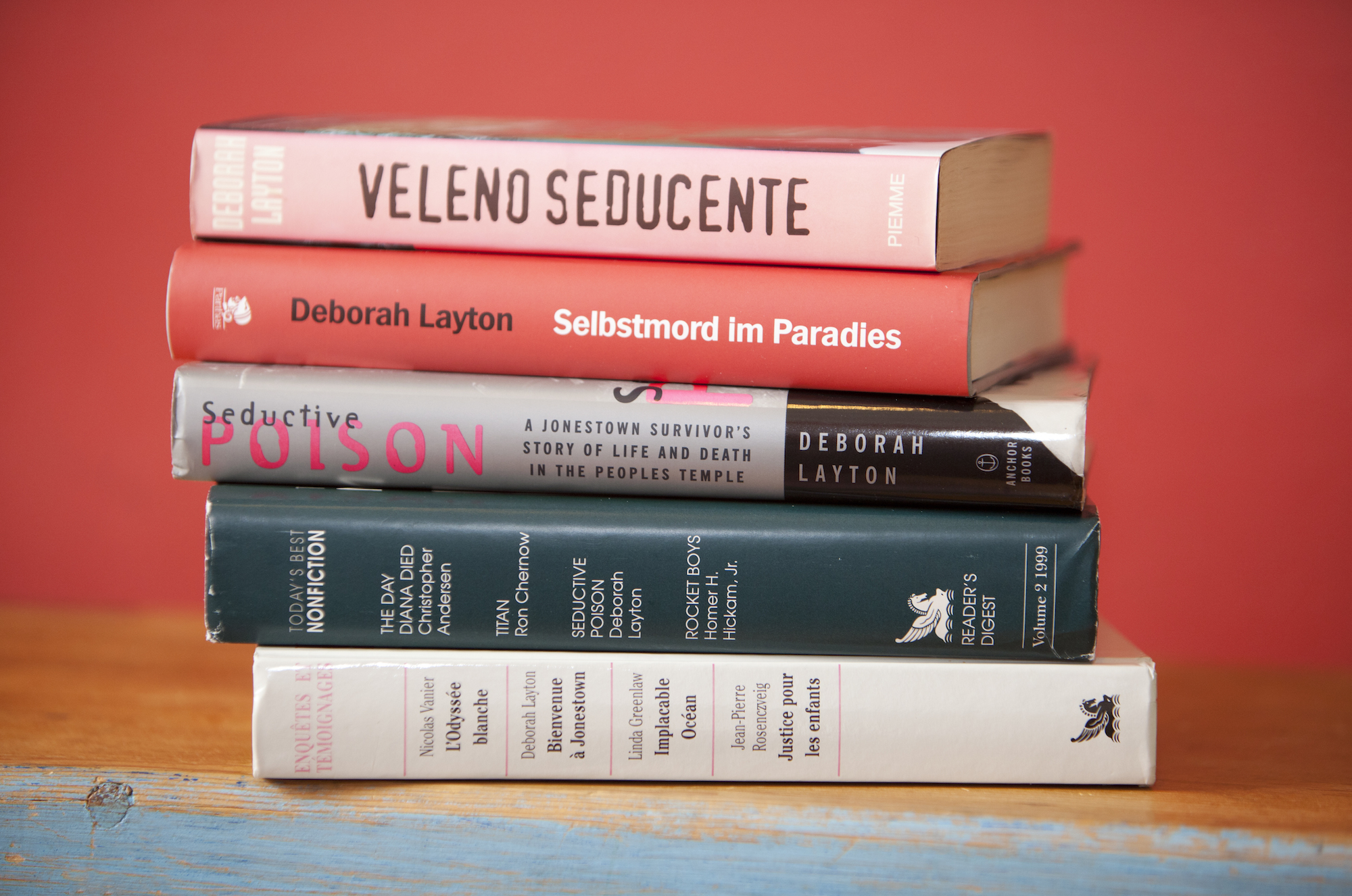

It’s a story that still haunts the American psyche. But Layton’s book, Seductive Poison: A Jonestown Survivor’s Story of Life and Death in the People’s Temple, gives an insightful look into what drew people to the church and how it all devolved into death and suffering.

While some people might wonder why Layton would write a book like Seductive Poison, I can totally relate. Like her, I was raised in a religious, cult-like movement. Several years ago, after I broke all ties with my traumatizing “spiritual” upbringing, I started a band called King Woman, and used it as a vehicle to work through some of my own pain. The project has helped free me from my past and essentially saved my life. As we approach the 39th anniversary of the Jonestown Massacre, I reached out to Layton to talk about her experiences overcoming psychological trauma.

VICE: What drew you to Jim Jones and the Peoples Temple?

Deborah Layton: I was searching to be a part of something. When I was 17 and I went to a Peoples Temple meeting, and Jones kept on saying, “You have qualities your parents don’t recognize.” Suddenly a grown-up thought I was special. That was the hook. That was the beginning.

What were some of the red flags you noticed once you were immersed in the Peoples Temple?

No one was allowed to smoke or drink. At the great age of 18, I thought this was going to be difficult. I had just come home from boarding school in England and was still a troubled kid. My parents thought the Peoples Temple’s college campus was a great place because they had a dormitory. But unbeknownst to them, we were driving all the way up to Ukiah, California for all-day meetings… The intense indoctrination had begun. With Jones, it was, “Can’t you give up a little bit of your own life and not be so selfish?” He preached as if we were joining the Peace Corps.

How’d you get to Jonestown, Guyana?

First, you had to fly down there from America. He had paid Guyana millions of dollars to have this piece of land in the middle of nowhere. If you tried to get out, you couldn’t find your way back. The jungle became our bars.

Why did you decide to escape the Peoples Temple?

It was terrifying. The minute I got there, I knew I wanted out. I knew I had made a really scary decision: I had taken my mother, who was previously in Nazi Germany, into yet another concentration camp.

The people I had known as so vibrant in the United States looked like a leper colony. Once you were in there for a while, you were not the same person. Jim Jones was so fucking scary. He knew how to lure people in and then frighten them to death.

For example, every grown-up was subjected to “the box.” It was used to frighten us into shutting up and abiding by frightening rules. Plus, there were armed guards, and you only had rice water soup. [I couldn’t even] spend time with my mother because that would show I was weak, and I had to prove otherwise.

You were subjected to humiliating “catharsis meetings,” where everyone would criticize whoever was “on the floor.” What was that like?

Catharsis meetings were to break your spirit. He wanted me not to trust anybody but him. He wanted me to lose all faith in myself so he could come back in and say, “What they made me do to you is horrific.” It’s all an evil mind game. You become so afraid, you try to live within these frightening borders that they’ve created. My God you want to run away. But you think that if you run away, they are going to find you.

What was the worst thing you saw in the meetings?

There was one inner-circle meeting when one of the husbands had molested a child. When it was found out, he was brought in. The whole thing was filmed so that he could be blackmailed with it. We all had to whip his scrotum and penis with a rubber hose. But he was never taken to a hospital. The man was cared for in Jonestown so no word would get out. Jim Jones subjected people to stuff like this when he wanted to teach them a lesson, or he thought they might want to leave. Jones was the closest thing to God that we knew.

What was it like after you left the People’s Temple?

When I returned to the United States, I started working at an investment banking firm that was all about following the rules, keeping your mouth shut, and working long hours. All the guys who worked there were into Erhard Seminars Training, which was an empowerment cult that took you on these long retreats where people would scream and yell at you. People could spit in your face. After seeing this, I thought, What is the difference? Everyone is susceptible to getting involved in something like this.

Since Jonestown, what have been your most powerful tools for wellness and recovery?

I think I was very lucky in that my father never turned his back on me. I took my mom, his wife, away from him to some place where she died. When I returned, he would cry. He would say, “Why didn’t you tell me?” But then he would hold me and say, “I got my baby girl back.” He was so conflicted. He loved me. In a lot of these places, these people have nobody to run to because their whole family is in there. But he never turned his back on me.

After being around an overwhelming amount of religious abuse, what does spirituality mean to you?

I would say I’m spiritual. I do not partake. I don’t like group stuff anymore. I don’t want to do that every Sunday. I did that for so many years. I just can’t do it now.

Yeah, church gives me the creeps. I can’t be there. Did the process of writing and releasing a book bring you a sense of closure?

It did. My book was just going to be about Jonestown, but when my editor saw it, she said, “Wait a minute, Debbie, you can’t just write about that! You need to go all the way back. People need to understand where you come from and why you were susceptible.” Then it became really hard for me to write.

Was there any information that you wanted to leave out at first?

When I got on that plane to escape from Guyana, I had to compartmentalize that I was leaving my mother behind. I felt I could not ever go back and visit it. When I was writing Seductive Poison, my editor said, “You have to write about your mother,” and I stopped writing for several weeks. I had a six-year-old. I found her little acrylic paints. I went outside, and I started painting our chairs and our planter boxes. It was a super hot day. There was no wind. And the back door of our house blew open, and I felt as though my mother was saying, “It’s time to come back and say goodbye to me.” That’s when I went back in and started writing about my mom.

Even after writing the book, has it been hard to talk about it?

When I finished the book, I went to Stanford to speak. That was outrageously cathartic. I thought the students were going to say, “Shut up!” But I got this standing ovation. I spent 20 years so afraid for anyone to know who I was and what I’d done, even though I blew the whistle, even though I was the one who went to Washington, DC. I spent so much time afraid that everyone would hate me. That shame is so vile.

Have you been back to Jonestown?

Right before my book came out, I was asked to fly down to do a documentary. When we got into Jonestown, I was going to go and find where my mother had been buried. Well, the jungle had completely retaken everything except for one area that had no plants in it. That was where the pavilion was, and that’s where all the people had died from cyanide poisoning. No plant had grown back.

Did you feel her spirit there?

I was intent on finding her essence and apologizing for leaving her, and then I realized she wasn’t there. I felt no spirits there. If you die in Auschwitz, your memory is not in Auschwitz. Your memory is where your wife was, where it was made before these horrific events. I felt relieved that I didn’t feel her or anybody else’s essence there. They had all fled… if there is such a thing.

Looking back, what is the single thing you want people to understand about this tragedy?

Nobody ever joins something they think is going to kill them. Nobody joins something that they think will rip them from their family forever. It happens over time. By the time you recognize it, you do not know how to extricate yourself because you have children, you have loved ones, you have family inside that you will never be allowed to see again. That’s why for so many of these organizations, there are people that want out, but they know if they leave, they will never see the people they care about. If we can figure out how to let people know they won’t be harmed if they run away, and that there’s some place for them to run to, I think we can save more lives.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

To purchase Deborah Layton’s book, visit her website.

To listen to King Woman, visit its BandCamp.

More

From VICE

-

Collage by VICE -

The author lurks outside an estate agents, Voigt-Kampff machine just out of shot. Photo by Zuka George -

Screenshot: Battlestate Games -

Jesus, Mary Magdalene, Judas Iscariot, and some fourth wheel at the Last Supper (All photos by Paige Taylor White)