This article was published in collaboration with the Marshall Project. Sign up for their newsletter.

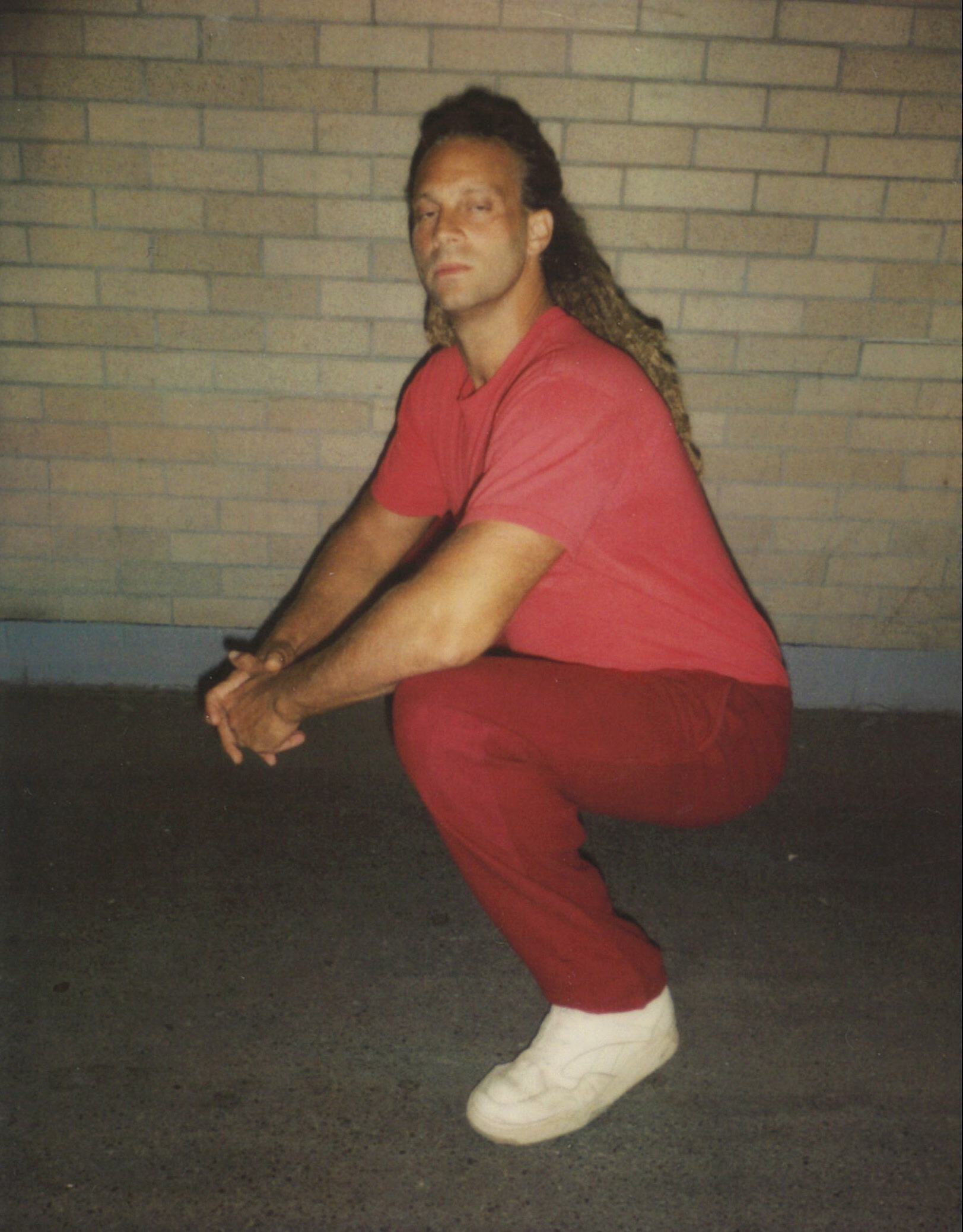

It was January 2006, and Josef Kirk Fischl was tucked away behind a 30-foot-high gray wall in C Block, one of Attica Correctional Facility’s toughest cellblocks. He had already served more than 16 years on a 25-to-life bid for a murder he committed when he was 19.

Videos by VICE

At the time, Fischl was sporting dreadlocks down his back. One day, filing out to the yard, he walked through a gauntlet of correction officers holding wooden batons, their arms sleeved in tattoos—skulls, dragons, spider webs wrapped around elbows. He was ordered to put his hands on the wall. It hadn’t taken long for the COs to home in on the white guy with dreads.

Once the corridor was cleared of other prisoners, an officer said to Fischl, “Cut those dreads. Take it back to your cell.”

The next day, a different CO stopped Fischl on the way to the mess hall and told him that only Rastafari were allowed dreads and that he had to cut his. Fischl said no, according to the officer, who gave him a misbehavior ticket for refusing a direct order. By the time of the ensuing disciplinary hearing, Fischl had already written to the chaplain and changed his religion from Jehovah’s Witness to Rasta. He was found guilty of the infraction but allowed to keep his dreadlocks.

Twelve days after the hearing, Fischl’s company (a tier of cells) had a seemingly routine shakedown. But when his cell opened, he recalled, two officers wearing black leather gloves rushed in and rained down blows on him. Beaten and handcuffed, Fischl was dragged off to “the box,” also known as solitary.

To Fischl, the beatdown was no mystery: The C-Block COs had been slighted when the reprimanded inmate got to keep his dreads. So they got payback.

Fischl received a misbehavior report saying he had assaulted the officers by lunging at them with a shank. At the disciplinary hearing, it was Fischl’s word against the COs’. At the time, there were no surveillance cameras in the cellblocks at Attica—Fischl had no evidence to counter the allegations against him. He was found guilty, and received nearly a year of box time plus the loss of all privileges during that period: commissary, phones, packages. (The New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision, or DOCCS, declined to comment on specific incidents described in this story.)

It’s worth pausing to note that Fischl has been on and off the caseload of the state prison system’s Office of Mental Health (OMH) and is sometimes given to psychotic episodes. So his account may not be entirely reliable.

Among many New York State prisoners, Attica has long been considered the worst maximum security joint to serve time in.

But for those of us who have served time in Attica, one of America’s most notorious prisons, Fischl’s ordeal was business as usual. Attica’s dirtiest little secret, as documented by Tom Robbins for the Marshall Project and the New York Times, is that for years, officers had been falsifying misbehavior reports and lying about being assaulted to justify using force on prisoners. From January 2010 to November 2013, there were 228 assault on staff tickets filed at Attica, according to a 2014 report by the Correctional Association of New York, a watchdog nonprofit. At the disciplinary hearings, 227 prisoners were found guilty of at least one infraction on the ticket. And the large majority, 212, were found guilty of the assault on staff claim, which typically meant several months in the box. The CO’s word prevailed against that of the prisoner in every case but one.

Among many New York State prisoners, Attica has long been considered the worst maximum security joint to serve time in. Near Buffalo, about 350 miles northwest of New York City, which is home for most prisoners, it’s a haul for families to visit. Seventy-six percent of the 2,026 prisoners are black or Hispanic; the approximately 600 COs are mostly white. The wall, the skies, the mood—they’re all gray, seemingly every day. Stories about setups and beatdown crews have long reverberated throughout the prison system. Over the years, the Correctional Association of New York has documented harrowing tales of harassment, pervasive racism, retaliation against prisoners filing grievances, excessive box time in disciplinary hearings, and more.

But that was before video surveillance came to Attica. By April 2015, cameras were being installed throughout the prison—as of January 2018, there were 1,875 cameras and 915 microphones, according to DOCCS. “The cameras are a valuable tool in the ongoing battle against drugs and contraband in the State’s prisons, as well as an asset in investigations into incidents involving both inmates and staff,” a DOCCS official said, adding that plans were underway for the installation of additional cameras at other state prison facilities.

Cameras at Attica have provided an unprecedented level of transparency and accountability for correction officers. And they’ve been followed closely by a remarkable occurence: Official reports of assaults on staff have dropped drastically. In 2014, the last year without surveillance, there were 64 assault on staff reports, according to a DOCCS report. The ten-year annual average was 50, and in no year during the period before cameras did the number drop below 30.

From May 2016 to May 2017, as cameras came close to being fully installed, incidents dropped nearly 80 percent from the last year without cameras, to 13. In about this same period, staff reported 40 percent fewer injuries than the previous year.

According to DOCCS, the decline of assaults on staff can be attributed in part to the cameras but also to several other recent initiatives, including additional training for security staff, de-escalation tactics, and a pepper spray program. These changes were introduced around the same time the cameras were being installed.

But I have a different interpretation of this data: Under today’s watchful eyes, Attica COs are less inclined to falsify misbehavior reports and make bogus allegations of assaults by prisoners than they used to be. They are also less likely to file false injury claims, which can result in months of paid leave at the taxpayers’ expense.

After reporting this story for two years as a prison journalist, gleaning data from official corrections reports, interviewing prisoners, COs, and the former superintendent, I can also say that cameras and microphones seem to have accomplished what once seemed impossible at Attica. They have begun to tame a violent us-against-them culture that formed decades earlier in the prison’s most defining moment.

The only question is, will the relative peace continue?

When people think of badass American prisons, they better think of Attica and the 1971 riot. Ever since, the prison has been romanticized—in Hollywood (Al Pacino in Dog Day Afternoon), in music (the other John Lennon’s “Attica State” or Nas rapping “I’d open every cell in Attica, send ’em to Africa”), in those iconic photos of prisoners in the yard, fists up (Power to the people!). The Attica uprising has also been demonized—lies told about the event, according to Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Heather Ann Thompson, helped fuel mass incarceration. A state commission wrote in 1972 that the police assault that ended the uprising was, with the exception of late-19th century Native American massacres, “the bloodiest one-day encounter between Americans since the Civil War.”

I landed at Attica in 2007. Six years earlier, while caught up in the drug-dealer lifestyle, I shot and killed a man on a Brooklyn street. Soon after, I was caught, tried, convicted and sentenced to an aggregate term of 28 years to life—25 for the murder and three more for drug sales. Of my more than 16 years incarcerated in jails on Rikers Island and in maximum security prisons in upstate New York, I spent nine in Attica.

I was fortunate to get involved with programs at the prison that helped me change my life. In a 12-step meeting hosted by civilian community members in recovery, I got sober. In a privately-funded college program, I earned an associate’s degree. In a creative-writing workshop taught by an English professor, I learned how to write. I took to journalism and soon saw Attica as a never-ending story.

Still, it was a nasty joint. I’d served time in other max prisons, but only in Attica did I see COs make their own rules. Only in Attica were men subjected to random frisks entailing the infamous “credit card swipe,” in which a CO would run his hand up the crack of a prisoner’s ass. Only in Attica did they restrict prisoners to once-a-week law library access. Only in Attica was I limited to two showers per week (in other joints, it’s three.) Only in Attica did shirts, sweatshirts, even sweaters have to be fully tucked. (It looked ridiculous.) Only in Attica did COs constantly carry their batons strapped to their wrists, tumbling them in and out of their hands like yo-yos. It was unsettling to be walking the corridors with a CO right behind you, baton in hand.

Turn around and you got, “Eyes forward!”

Wrapped in more than a mile of wall are piles of brick that make up Attica’s five cellblocks—A, B, C, D, and E. At one time or another, I lived in every one of them. The action—between prisoners, between COs and prisoners—went down in the corridors, in the cellblocks (A and C were the worst), the foyers, the companies, and the yard. Until recently, none of these areas had cameras.

Beatdowns were so common and calculated, we’d hear them but never see them.

For the most part, discipline in Attica followed this drill: Head down, clipboard and pen in hand, a CO would speed-walk the tier, taking the mess hall and yard list. Prisoners who weren’t on their bars would miss the list and starve and go stir crazy. No mess hall. No yard. If a prisoner yelled a heads up that the officer was coming, or if there was loud singing, maybe a freestyle rap battle, the COs would cut off the electricity on the entire company.

Sometimes the officer would make it more personal, taking to the catwalk in the back of the cells and yanking out the electrical wires or pulling the fuse for a cell of a particular prisoner. The prisoner singled out for special attention usually got an “asshole” tag on the cell electrical panel in the COs’ station, meaning his cell likely wouldn’t open for mess hall or yard runs. If the guy was lucky, some passing friend would toss him a few ramen noodles from commissary so he wouldn’t go hungry. It’s called being “on the burn.” It sucks.

On rare occasions, a prisoner would lash out in response. This is what I believe happened when Shondell Paul stabbed two A-Block COs in 2004. Back then, I was in Clinton Correctional Facility in Dannemora with his brother, Tajuan Paul. Tajuan, or “TP,” was my poker buddy, and we worked as porters. Together, the Paul brothers were serving more than 200 years for robbing and killing people at street craps games in Syracuse. What we heard was that Attica COs had been harassing and burning Shondell. He got tired of it. When his cell finally opened for a mess hall run, he had a seven-and-a-half-inch shank taped to his wrist. He casually walked into the foyer, slid the shank into his palm, and unleashed fury.

But calculated attacks like that were rare. When they happened, prisoners were happy to spread the news, as if they were celebrating a winning battle in the us-them war.

Most incidents were frustratingly reported by the prison rumor mill, and sounded a lot like this: Kenneth Harris, whose nickname is Justice, was nearly four years in on an 11-to-20 year sentence for robbery. After a disagreement with a favored prisoner, Harris said, it didn’t take long for C-Block COs to red-flag him, especially since his pedigree indicated he was a Blood. On March 19, 2014, Harris’s cell opened, he thought, so he could help cut hair in the C-Block barbershop, as he’d done a few times before. When he entered the cellblock lobby, he told me, COs told him to grab the wall. It was the so-called beatdown crew. They latched the foyer doors and posted officers at both ends of the corridor.

The history of false misbehavior reports at Attica goes back at least as far as the uprising.

Then it went down—blows to the back of his head. Harris hit the deck, curled up and covered up. Then they put the boots to him, chipping one of his front teeth and loosening another.

I was in C Block when this happened. Beatdowns were so common and calculated, we’d hear them but never see them. I’d be in my cell, hear batons tap on the floor—clack clack clack—and then two bells like fire alarms. Then the boom of the boots, keys jangling, COs running to the scene.

“Stop resisting!”

“I’m not resisting!”

Then screams. Then silence.

Harris’s incident sounded like so many before and after. I’d become numb to them. Apathy provided a psychological safe space in Attica; it’s better to appear stoic and indifferent than shocked and empathetic. At first it’s an act. Then it’s not.

A lumped and bruised Harris was taken to the prison hospital, where he told a nurse about his teeth. Then it was off to the box. Two days later, he said, he was called out to the dentist, who bonded the chipped tooth and performed a root canal on the loose one. When Harris received the misbehavior ticket—assault on staff, weapon, and more—it said that while he was being frisked on the wall, a shank fell out of his waistband and as an officer bent to grab it, Harris kneed him in the head. Then, a report detailing the use of force claimed, three COs used strikes, mechanical restraints, and body holds to get a combative Harris under control. According to the report, the only injury Harris suffered during the incident was an abrasion on his left clavicle.

At the disciplinary hearing, Harris pleaded not guilty and tried to explain that he’d never seen the shank before and that the incident didn’t go down as described in the ticket. Nonetheless, he was found guilty and received 160 days box time, 200 days loss of privileges, and three months recommended loss of good time on his sentence.

The history of false misbehavior reports at Attica goes back at least as far as the uprising. On September 13, 1971, the fifth day of the takeover, COs and state police troopers in Grim Reaper get-ups—gas masks, raincoats, no name tags, locked and loaded—fired more than 400 rounds in the D yard. Among the dead were 29 prisoners, six officers, and four state workers, including CO William Quinn, who was pummeled to death when the uprising began. Adding three prisoners stabbed to death, and another CO who died a month later from injuries sustained during the riot, the toll was 43. When the gas cleared, state officials reported that the prisoners had killed hostages—slit their throats, mutilated their faces, disemboweled one, and even castrated a CO and stuffed his genitals in his mouth. All lies.

Later that week, Dr. John Edlund, a medical examiner, revealed that all the hostages had died of gunshot wounds. But the prisoners never had guns.

After the uprising, there was payback. Prisoners were prosecuted, most for their roles in Quinn’s murder and the deaths of the three stabbed prisoners. A couple were convicted, a few were acquitted, and scores were indicted. Only one state trooper was ever indicted—for reckless endangerment (the charges were later dismissed).

In March 1975, a lawyer from the prosecution’s camp leaked to the New York Times that overwhelming evidence, which would implicate some of the COs and troopers in some of the killings, was being ignored. Weeks later, the Times ran an expose and the administration started scrambling. In December 1976, New York Governor Hugh Carey gave sweeping clemency to the prisoners and blocked disciplinary action against law enforcement. Since then, my take is that many Attica COs, some of whom were related to or friends of officers killed or wounded in the uprising, felt peer pressure to live up to the prison’s notorious reputation and enact payback. They maintained control by instilling fear, battering prisoners who were easy prey.

For decades, the Correctional Association, and prisoners themselves, called on state legislators to put cameras in Attica to help protect the population from violent COs. In 2007, when I arrived, Attica had cameras in only a few areas of the prison. One was the mess hall, which was housed in a sublime neo-Gothic brick structure with vaulted ceilings and thick, marble-like columns, and contained row on row of metal picnic tables. A CO sat in an elevated glass bubble with his thumb on the tear-gas button. But nothing ever really happened in the mess hall. Cameras were also installed in the special housing unit cellblock, or the box, as well as the secure therapy areas. But nothing much happens there, either, because everyone is locked in.

In 2014, a swath of eye-in-the-sky cameras were installed in the ceilings of Attica’s two visiting rooms. While there was a need for them (they would probably deter and catch some smuggled contraband like drugs, which contribute to much of prison violence), I was curious why cameras weren’t going where they would capture the real eyebrow-raising stuff. According to the rumor mill, the correction officers union had a say in where the cameras were being installed—I think the security staff just didn’t want Big Brother in Albany watching how they maintained order.

Then, in February 2015, the Marshall Project and the New York Times co-published Tom Robbins’s story “Attica’s Ghosts,” about three officers who were indicted for the near-fatal 2011 beating of a prisoner named George Williams—the first in a series investigating violence by COs against inmates in New York state prisons.

It was the first time in state history that a guard had been prosecuted for brutality against someone in prison, according to the Correctional Association. A plea deal was struck a day after the article was published: In exchange for quitting their jobs, the COs pleaded to a single misdemeanor count. (In April 2016, the Marshall Project and New York Times series was named a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in investigative reporting.)

By the summer of 2015, a few months after Robbins’s first piece ran, cameras and microphones were being installed throughout Attica: in the corridors, yards, cellblocks, foyers, stairwells, companies, everywhere.

I wanted to ask the man in charge what prompted this sudden surge in surveillance. At the time, that was Dale Artus, a clean-cut man in his 50s who sports a politician’s smile. Artus began his career as a CO and came up through the ranks to become superintendent. In August 2016, he strolled into the cellblock while I was swinging a mop. It was good timing—Artus doesn’t usually give interviews.

“There’s been some hiccups, but those cameras are HD clear.”—Attica correction officer, 2016

“I give you a lot of credit,” I said, preparing to lay it on thick. “A lot has changed since you’ve been at the helm. The cameras have really made a difference.”

“Yeah, I agree,” he told me. “A few days ago, in the metal shop, an inmate punched a civilian.” (Civilian instructors work in the metal shop at Attica, where prisoners make desks and lockers for New York municipalities.) “COs responded, contained it, and took the guy to the box. If that had happened a couple of years ago, John, you know what would have happened.”

“So let me ask you this, how are the COs feeling about the cameras?”

“Some couldn’t handle them,” Artus explained, cocking his head to the side, palms upward. “So, they had to go…. Some retired, some transferred to different prisons, some bid different posts.” In the end, it was the right thing to do, he said, and it’s made a huge difference. (In an email, a DOCCS spokesperson said that attrition and requests for reassignment for correction officers have not changed at Attica since cameras were installed.)

When I asked him if the cameras were a direct result of Robbins’s article, he told me they had been approved for some time. “But what that article did do was put Attica under a microscope,” he added. “And because of that, cameras and mics were installed all over, every crevice, no blind spots. And I welcome that.”

(Reached by the Marshall Project and VICE in February, Artus declined to comment on the conversation.)

With today’s transparency, officers are compelled to be more professional. In October 2016, I spoke to a chatty, old-timer CO.

“There’s been some hiccups, but those cameras are HD clear,” he told me, asking to remain anonymous to avoid angering his colleagues.

“And the mics…. Oh boy! If a mouse pissed on a cotton ball, you’d hear it.”

If he were telling this to me, I thought, then he must have been telling his peers, too—which meant COs were changing the way they operated.

A young officer, who also asked me not to use his name for fear of reprisals, told me he welcomes the oversight. “Look man, in many ways the cameras are good,” he said. If they had been in place earlier, he added, there would have been countless fewer violent incidents between prisoners and officers.

With Big Brother watching, some prisoners are now more nervy with COs. Take an incident in the fall of 2016 when Gary McKenzie—21 years, manslaughter—was walking with a group of prisoners, including me, headed to evening program. Paired off, no talking, we knew the deal. As we passed some COs, McKenzie was pulled off the line by an officer who told him to tuck in his shirt. McKenzie replied that his shirt was tucked in. (It was sloppily tucked.) A back and forth ensued. The CO told McKenzie to get back in line, calling him an “asshole.” McKenzie returned the insult. The COs did nothing. I was shocked. The next day, McKenzie received a misbehavior report for refusing a “direct order.”

At the hearing, he pleaded not guilty and requested the videotape in order to prove that his shirt was indeed tucked in. The lieutenant reviewed the tape and dismissed the ticket. Before cameras, prisoners hardly ever got around direct-order tickets because the word of the CO had always trumped the prisoner’s. Now, the tale of the tape decides.

Many of the old guard feel Attica has lost its “overall team spirit”—or at least that’s how CO Gary “Preacher” Pritchard characterized the changing Attica workplace culture in a deposition for a lawsuit against him. It’s possible Preacher got his nickname from prisoners mispronouncing his real name, yet, with tattoos of “Jesus” and quotes like “Angels All Around Me,” the name fits. He is given to self-righteous comments in an eerie drawl, posturing in front of his peers and prisoners in earshot with lines like, “We’re the ones who protect society from these guys.”

Over his 25-plus year career, Pritchard’s been named in at least 24 federal civil rights lawsuits filed by prisoners, as reported by Robbins. I was around Pritchard for years. With a blond crop cut, baton in hand, backed by his crew in blue, Pritchard talks slow and fishes for fear in wide-eyed newbies; he’s on the prowl especially for sexual predators and LGBTQ prisoners. In 2015, the state settled a federal lawsuit against Pritchard and another CO for allegedly beating up transgender prisoner Misty LaCroix, blackening her eye and breaking her rib. LaCroix received $80,000.

At the end of 2015, a sunken-faced Pritchard appeared while working on my company in A Block. Cameras and mics in the area were recently operational. There was loud music, weed in the air, shouts echoing up and down the company—and, surprisingly, Pritchard kept his cool. The prison din was something he’d never tolerated in the past. Now, he’d sit at his station, often in conversation with another CO, seemingly tamed by the cameras and mics.

That’s when I realized Attica’s culture really was beginning to change.

And yet it bothered me that society would define the lives of me and my peers by our worst deeds and be none the wiser about Pritchard’s. It bothered me that he would never be punished for his actions and that he was protected by a corrections union and received, through their negotiations, a comfortable six-figure salary and generous pension.

On November 15, 2016, I was transferred to Sing Sing, just up the river from New York City. The prison is much less intense. Batons stay on hips. COs talk to you, not at you. As a group, they’re more diverse than Attica officers; here they are mostly black and Hispanic, and many are women. When taking the mess hall and yard lists, COs stop at your cell and make sure they hear your request. When prisoners yell “walking” to alert others, COs don’t take it as a slight and cut the electricity or burn men on the mess hall and yard. Sing Sing houses about 1,600 prisoners, several hundred fewer than Attica. Cameras are not installed throughout the prison, and yet the ten-year annual average for assault on staff reports is 30, dropping as low as 15, according to DOCCS data from 2005-2014.

I’d surmise that most of those reports are accurate. In Sing Sing, some prisoners forget that officers have the same power to make or break their day, just like the ones upstate. One recent morning, a group of us were waiting in the corridor to go to the yard. A CO at the end of the corridor was also apparently waiting for clearance to let us out. A voice from the crowd yelled, “What you waitin’ on, house nigga? Let us out!”

That would’ve never happened in Attica. In my short time here, I’ve seen prisoners yell at COs, get in their faces. I even saw a fist fight in the yard between a prisoner and an officer, who at one point was dropped by a left hook. When backup came, they didn’t pound on the prisoner; instead, they cuffed him and took him to the box. Prisoners made dopey comments, laughing at the CO. I felt like we were the villains. For the first time, I felt, maybe Attica COs knew what they were doing all along.

It was a fleeting thought.

Recently, a prisoner I was with in Attica arrived in Sing Sing, and told me the worst of the old guard had left, the setups and beatdowns were over, and COs now use pepper spray instead of batons. He also told me the prisoners have turned more aggressive as COs demonstrated their restraint before the cameras. I can’t help but sympathize with the new generation of Attica COs, who enjoy less generous pensions and closer scrutiny while paying for the sins of their predecessors.

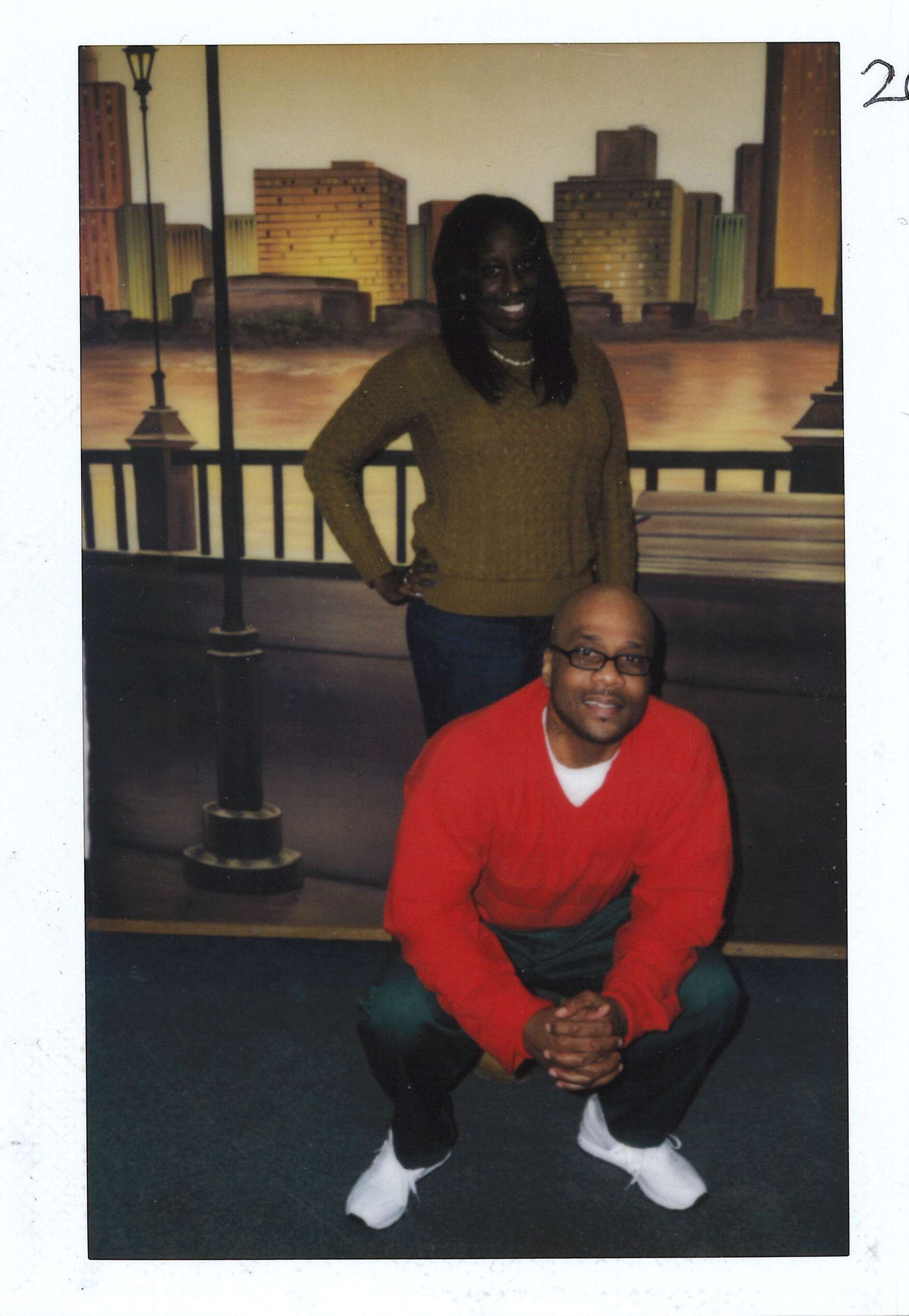

Today, Kenneth Harris, the target of that Attica beatdown, is here with me in Sing Sing. He told me the only violent blot on his ten-year institutional record was that alleged assault on staff. “That shit was crazy,” he told me in the barbershop, where he was buzzing another prisoner’s hair. “From the box I went to Clinton, couldn’t get a program, my people were harassed on the visit—all for some shit I didn’t even do.”

Until a recent transfer, Josef Fischl, of the dreadlock incident, was also here with me in Sing Sing. He was sporting a buzz cut. His institutional record is packed with misbehavior reports, but in almost 30 years he’s never cut or stabbed a prisoner or CO—the Attica report is the only one, as of fall 2017, that said he was violent with a weapon. He has been written up for other assault on staff violations, however. “I have these episodes,” he said, smiling, “and things sometimes get out of hand.”

Fischl has been variously diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. In past lives, he told me, he was crucified between two men in a desert; he helped build the pyramids; he was an American Indian. One time, he said, he felt the strength of the T-Rex dinosaur he had been in one of his fantastic incarnations. “I was too big for that prison,” he told me. “Those measly human COs couldn’t hold me.”

Several months ago, Fischl had an episode in Sing Sing. He was crawling like a crab in the yard, vibing the sea creature he told me he used to be back when Earth had no land. Sing Sing COs escorted him to disciplinary, tested his urine for drugs. When he became psychotic, they restrained him, non-violently, and took him to mental health. He was sent to the Central New York Psychiatric Center.

Psych meds make him feel like a zombie, so he doesn’t take them. He’s intense, almost to the point of being annoying, but in our conversations, he’s been lucid. I asked him if, given his file at the Office of Mental Health, he was sure his story of the Attica COs wasn’t a psychotic episode. He smirked, leaned his head to the side, and squinted his eyes at me as if I were stupid.

“Nah man, I wasn’t even seeing OMH back then. They beat me up and set me up because they didn’t like my dreads,” he said. “Come on Johnny, you were there, you know what they do.”

I nodded.

John J. Lennon is a contributing writer at the Marshall Project whose work has also appeared in the New York Times, the Atlantic , Quartz, the Chronicle of Higher Education , the Hedgehog Review , and other publications.

More

From VICE

-

Mandatory Credit: Photo by Jordi Boixareu/ZUMA Press Wire/Shutterstock (14463923d) Oasis Of The Seas (Royal Caribbean International) cruise ship's funnel give off smoke in the port of Barcelona. Sulphur oxide and nitrogen oxide emissions makes Barcelona port worst in Europe mainly for cruises ships air pollution. Environment Air Pollution Barcelona Spain – 05 May 2024 -

VICE host Matt Shea with Andrew Tate, before their relationship went south. Credit: VICE/BBC -

Jake Burghart -

Flooding in Nigeria in 2022. Photo by Xinhua/Shutterstock.