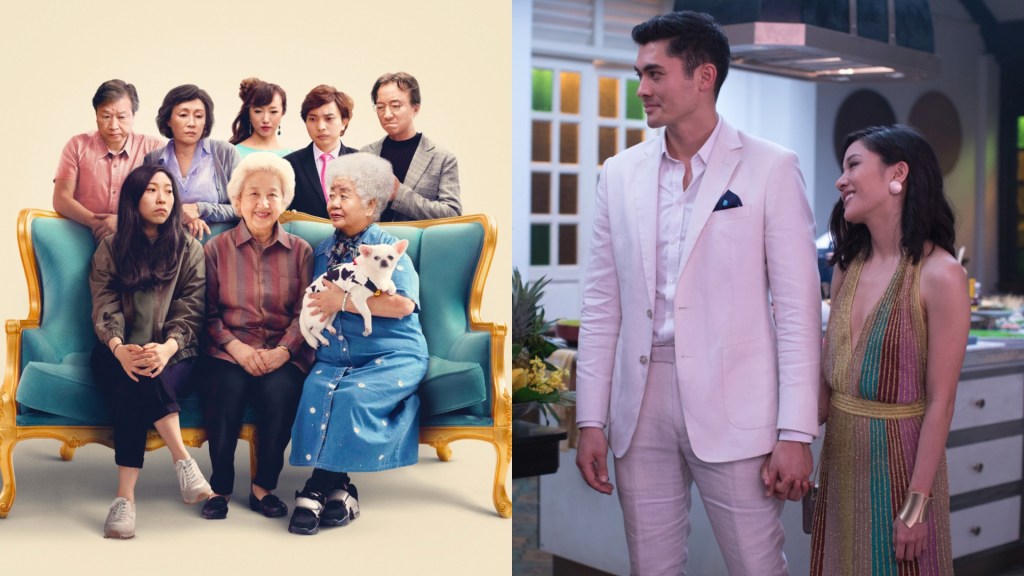

Crazy Rich Asians was just the beginning. The first major Hollywood film in 25 years to star a majority-Asian cast, last year’s adaptation of Kevin Kwan’s 2013 novel soon also claimed the title of the most successful rom-com in nearly a decade. The movie wasn’t perfect—what rom-com truly is?—but for viewers whose stories have been excluded from Hollywood’s mainstream narrative, it suggested a shift. To Hollywood, meanwhile, its success proved the power of the Asian American market, catalyzed by initiatives like #GoldOpen to get people to theaters. Echoing the sentiment around Black Panther, director Jon M. Chu stated, “It’s not a movie, it’s a movement.”

Chu’s film marked an undeniable turning point for modern Asian American film representation. Netflix dropped the wholesome romance To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before starring Lana Condor just days later. In theaters soon after came Searching, an internet-driven tale of a father looking for his missing daughter, which made John Cho the first Asian American actor to lead a major thriller. In May, Netflix released Always Be My Maybe, a food-focused rom-com featuring Ali Wong, Randall Park, and Keanu Reeves.

Videos by VICE

With the release of Lulu Wang’s The Farewell, the current push of Asian American representation has its newest figurehead. The Farewell stars Awkwafina as a Chinese-born American immigrant who returns to China to visit her family’s dying matriarch, who hasn’t been told she’s dying. Hailed for its nuance and humanity, the movie has already brought in the year’s largest per-theater average, unseating Avengers: Endgame. As Wang recently told the Atlantic, The Farewell has been met with emotional responses from viewers who see their own family dynamics reflected.

Hollywood’s shift towards Asian American stories doesn’t show signs of stopping. Less recognized but also in theaters right now is Stuber, a buddy-cop movie starring half-Filipino Dave Bautista and Pakistani American Kumail Nanjiani. Alan Yang’s upcoming Tigertail will star John Cho as a Taiwanese immigrant in the United States in the 1950s, and Lee Isaac Chung’s Minari will tell the story of a Korean family in rural Arkansas in the 1980s. Buzziest of all, at San Diego’s Comic-Con this weekend, Marvel announced Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings, which will also star Awkwafina and make Kim’s Convenience actor Simu Liu Marvel’s first Asian superhero.

The current movement is undoubtedly worth the praise it’s earned. It’s been just two years, after all, since Scarlett Johanssen was controversially cast as the Japanese character Motoko Kusanagi in the live-action Ghost in the Shell. Calls of whitewashing have dogged Netflix’s adaptation of Death Note, Marvel’s Doctor Strange, and Aloha, in which Emma Stone plays a quarter-Chinese and quarter-Hawaiian character. That disappointing standard makes it all the more groundbreaking for Asian roles to actually go to Asian actors.

But while the current wave of movies makes the necessary first steps of representation, we must interrogate whose stories are being told. Judging by the roster of what’s hitting theaters, Hollywood—and the people talking about its successes—seem stuck in the problematic loop of conflating “Asian” with “East Asian,” boiling down the “Asian American experience” to one phrase that doesn’t actually suit all. At best, it’s proof that progress is slow; maybe, in a few years, Southeast Asians might have a Farewell moment, too. At worst, however, it reinforces boundaries around whose representation matters, and alienates people who are already cast aside within the “Asian” category.

An Asian, defined by the Census Bureau, is anyone who has origins in “the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent” including “Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine Islands, Thailand, and Vietnam.” According to a 2018 fact sheet, the United States’ Asian population is led by 4.9 million Chinese (excluding Taiwanese), 4.1 million Indians, 3.9 million Filipinos, 2.1 million Vietnamese, 1.8 million Koreans, and 1.5 million Japanese.

By the year 2000, South and Southeast Asians made up about 12 percent more of the country’s Asian population than East Asians, according to the website AAPI Data, which analyzes demographic data and research on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. That divide has only grown: in 2016, South and Southeast Asians made up over 20 percent more of the entire Asian population than East Asians.

At its core, the current breakdown of Asian American film representation falls short because it doesn’t quite line up with what Asian America actually looks like. The stories and the people in them skew mostly East Asian—but what about everyone else? In the big picture, prioritizing the East Asian narrative in terms of Asian American representation pushes South and Southeast Asians out of the conversation, groups whose ownership of the term “Asian” is already unfairly contested.

As part of a post-election phone study, the 2016 National Asian American Survey asked people across the United States to identify who they considered Asian or Asian American. The majority of the Black, white, and Latino participants considered people with Chinese, Japanese, and Korean descent to be Asian or Asian American, but when asked about South and Southeast Asians, people were more resistant to inclusion. Forty-one percent of white participants and 15 percent of Asian American participants considered people of Indian descent as “not likely to be Asian,” and the rate of doubt was even higher when it came to people of Pakistani descent.

As Jennifer Lee and Karthick Ramakrishnan, two authors of the study, wrote in an analysis, creating boundaries of a specific and selective Asian American narrative “affects our understanding of anti-Asian prejudice and discrimination.” While media representation is just a small step in larger political struggling, perpetuating divides in the demographic conversation “risks promoting an incomplete portrait of Asian Americans that ignores more threatening, dangerous, and even deadly forms of anti-Asian discrimination.”

In Hollywood, Asian actors with backgrounds outside East Asia have faced a troubling bind when it comes to casting: appearing “ethnic,” but not in a way that falls in line with the roles available. Disney’s early 2000s classic Lizzie McGuire starred Lalaine Vergara-Paras as Lizzie’s Mexican American best friend, Miranda Sanchez. Her identity on the show was bolstered by things like a family trip to Mexico and a Dia de los Muertos scene with her parents, but the mononymous Lalaine was actually Filipino and encouraged throughout childhood to “look as ‘white’ as possible.”

In recent years, to be fair, TV has given more spotlight to South and Southeast Asians. While the criticisms of her approach to diversity have been valid and vocal, The Mindy Show and The Office made the Indian American Mindy Kaling a household name. The creators of the CW’s Crazy Ex-Girlfriend put an active focus on Filipino American culture to mirror Vincent Rodriguez III’s background, and NBC’s Superstore stars Manila-born Nico Santos as a Filipino worker at a Walmartesque store in Missouri. ABC is developing the Hawaii-based Ohana, in which “each of the four protagonists is of a different mixed ethnicity—half-white, half-Japanese, half-Filipino and half-black,” according to the Hollywood Reporter.

Even in Hollywood’s current climate of creating space for the Asian American story, the ideas of South and Southeast Asians being somehow not the “right kind of Asian,” or not being “Asian enough” remain. “A talented Filipinx actor friend of mine is meeting with new agents and one just told him that Filipinos are a ‘hard sell’ and that she ‘couldn’t do anything with that,’” Crazy Ex-Girlfriend actress Tess Paras tweeted on Friday. “Pursuing dreams is so hard and I read shit like this and want to give up,” Filipina American actress Charlene deGuzman wrote in response. “But then I remember when I was little I never saw anyone like me on TV or in film and it made me feel like we didn’t exist and I really really want to be that person for someone and I’m going to die trying.”

These problems are compounded when it comes to mixed-race Asians, but especially to Black Asians, who feel the brunt of both erasure and anti-Blackness. With a Black father and a Filipina mother, actress Asia Jackson is an advocate for Black Asian representation and a critic of the colorism that can pervade Asian communities.

After Teen Vogue published a round-up of “29 Asian Actors You May Not Know But Should” last year, Jackson highlighted the difference in perceptions of who counts as Asian by pointing out that “10 were mixed with white, and 0 were mixed with black.” Her viral Twitter thread that followed identified notable Black Asians and Pacific Islanders, including On My Block‘s Jahking Guillory, who is Guamanian and Black; the Chilling Adventures of Sabrina‘s Tati Gabrielle, who is Korean and Black; and Insecure‘s Tiana Le, who is Vietnamese and Black.

“Being half Black instead of the default half white, I find that Black Asians are nearly entirely erased from the conversation of being Asian,” Jackson recently told Inkstone News. “Like, I’m not even allowed to audition for Asian roles because Hollywood’s vision of Asian is just East Asian, even though there are Southeast Asians who look exactly like I do: same brown skin color, same hair texture, all of it.”

Hollywood’s continued focus on a “certain type” of Asian might also be working to its detriment in a logistic sense. Deadline’s recent announcement of Taika Waititi’s Thor: Ragnarok sequel was coupled with a note about the now-postponed Akira reboot. “The project had been on the rocks for weeks,” it read, “with word in town that it is a difficult film to cast ethnically at its high budget, in this moment of political correctness.”

If Hollywood realizes there’s value in telling Asian American stories authentically, then perhaps it will start to look further than the faces who’ve spearheaded the movement thus far, creating opportunities for a broader range of actors to live their own stories and identities and for a broader range of viewers to find something to relate to. For now, some viewers remain eager to see closer approximations of their experiences, even if Hollywood remains imperfect.

“I know CRA won’t represent every Asian American,” Constance Wu wrote on Twitter last year in a statement to the movie’s critics. “So for those who don’t feel seen, I hope there is a story you find soon that does represent you. I am rooting for you. We’re not all the same, but we all have a story.”

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Bettina Makalintal on Twitter.