Claudia Weill’s 1978 film Girlfriends pre-dates the Bechdel test, but it was one of the first movies to truly, thoughtfully explore the intricacies of female friendship. When I watched it for the first time a couple of years ago, I was jarred by its immediacy and relevancy, despite its being nearly 40 years old.

When I saw the film for a second time recently, at the Quad Cinema in New York City, a line for the sold-out screening extended the length of the theater lobby. I was surrounded by women who could have seen the film when it first came out, as well as young girls with silver-dyed hair. There were twenty-something men in thick framed glasses and older gentlemen reading newspapers. The crowd was a testament to the film’s enduring resonance and its status as a cult classic, beloved by filmmakers like Wes Anderson and Greta Gerwig.

Videos by VICE

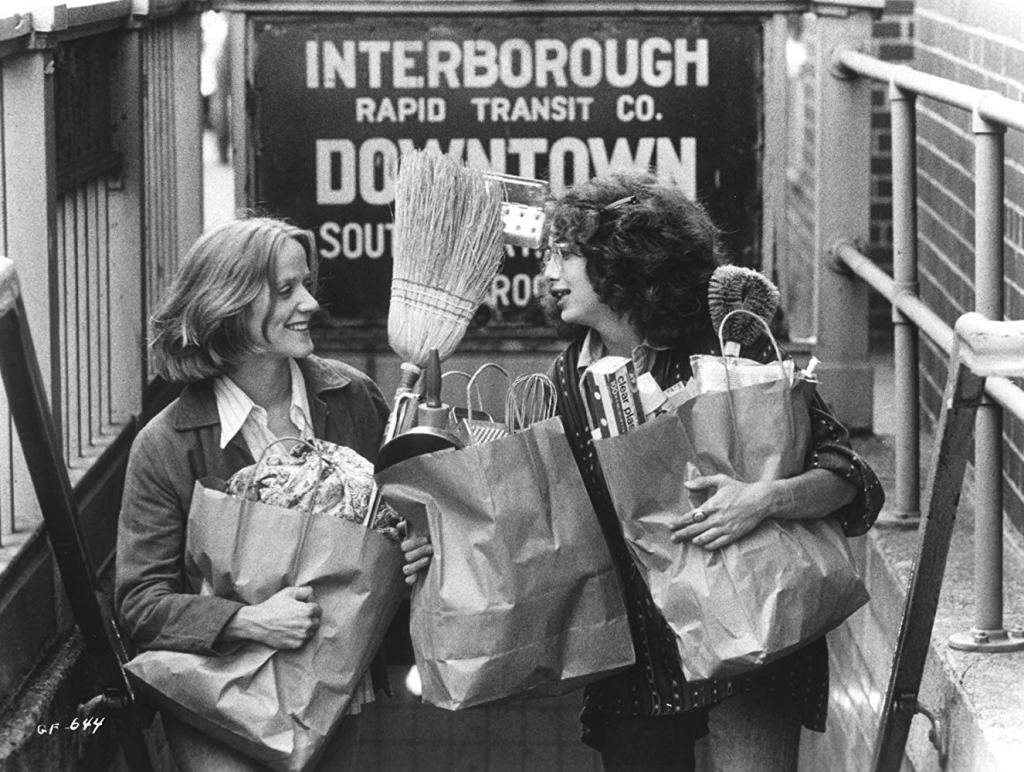

Girlfriends was one of the first films to remove male-centric narratives from its major plot points. Romantic interactions with men form its secondary stories, not its primary ones. Instead, it follows two friends, Susan Weinblatt (Melanie Mayron) and Anne Munroe (Anita Skinner), as they navigate their changing, individual lives alongside, and sometimes in reaction to, their relationship with each other.

Susan and Anne start out sharing a one-bedroom apartment in New York City, piled with boxes and bereft of ornamentation save for Anne’s mattress on the living room floor. Jewish and bespectacled Susan is an aspiring photographer, while slim, WASP-y Anne is an aspiring writer.

Theirs is a close friendship with nebulous boundaries, as so many friendships between young women are, with Susan photographing Anne in the early morning light while she sleeps, and Anne asking for feedback on a poem while Susan uses the bathroom.

Via short beats that punctuate the film and illustrate the passage of time, we learn that Anne has met a man she will marry and have a child with, often struggling to find time to write. Susan challenges herself as a photographer while also traversing the terrain of singledom (and relationship-dom) while living alone. We see Susan transform the apartment she shared with Anne by adding accoutrements like red paint, a hammock, and a shoe rack—cementing her solitary path yet beginning to achieve her goals.

Throughout the film, Susan and Anne simultaneously envy and admire one another’s lives, each feeling stuck in their own. They frustrate each other and are driven apart, only to reconnect when Anne confides in Susan and makes a difficult choice at the end of the film.

And yet, despite their nuanced and individual flaws, the film doesn’t judge or condemn either character—a novel concept in 1978—never deifying one woman’s choices over the other. “I tried not to idealize the single life or the single-r life,” Weill said during a conversation after the screening at the Quad. “The non-married life is not as romantic as it seems. The married life is not nearly as idyllic as it seems.”

“There was a novel by Eleanor Bergstein called Advancing Paul Newman, and she wrote the script for my second feature, It’s My Turn,” Weill added. “The last sentence of the first chapter of Advancing Paul Newman was, ‘This is the story of two girls, each of whom suspected the other of a more passionate connection to life.’ That said, it really intrigued me and really set me off in making this film.” Weill also said that Girlfriends was inspired by the Katherine Mansfield short story “Bliss,” in which a woman gets married and has a baby, thinking her life is perfect, but is then suddenly drawn to the life of a young single woman.

Weill presented her idea for Girlfriends to her friend, the screenwriter Vicki Polon, who wrote the film’s witty and occasionally biting dialogue and helped shape its complex, touching story. The film never questions its characters’ sex drives, their career choices, romantic partners, or even the abortion one character chooses to have. For a film released just five years after the landmark Roe v. Wade decision, it’s no small feat.

Girlfriends earned critical acclaim when it came out. The film was invited to the Directors’ Fortnight at the Cannes Film Festival, won the People’s Choice Award at the Toronto International Film Festival, was proclaimed one of the top ten films of the year by the National Board of Review, and garnered BAFTA and Golden Globe nominations for Mayron and Skinner respectively. Film Quarterly praised Weill’s direction of the film for its “depth of characterization, the economy of the narrative development, the richness of the backstories, and the concreteness of the choices.” Variety called it “warm, emotional, and at times wise.”

And yet, despite its critical successes, the film was not a mainstream success. This greatly befuddled renowned director Stanley Kubrick who, when asked about new trends among directors like Scorsese and Spielberg in the early 1980s, instead mentioned Weill and Girlfriends. “I think one of the most interesting Hollywood films—well, not Hollywood. American films—that I’ve seen in a long time is Claudia Weill’s Girlfriends,” he said. “That film, I thought, was one of the very rare American films that I would compare to the serious, intelligent, sensitive writing and filmmaking that you find in the best directors in Europe. It wasn’t a success. I don’t know why; it should have been. Certainly I thought it as a wonderful film. It seemed to make no compromise to the inner truth of the story.”

Today, Girlfriends is known and beloved by filmmakers, including Lena Dunham, Greta Gerwig, and Wes Anderson, among others. Weill has since had a long, successful career as a director of television, theatre, and film, but Girlfriends is still not known by a majority of mainstream audiences. It’s a cult classic at its most niche. Yet the film’s impact on contemporary narratives is undeniable. Gerwig’s film Frances Ha was accused of ripping off the Girlfriends storyline, but Weill disclosed at the Quad that she is flattered by the film and sees it more as an homage.

Dunham hadn’t seen Girlfriends until after she made Tiny Furniture, but as she told the Criterion Collection in 2012, it still feels like one of her biggest influences. And to be sure, movies like Frances Ha, Lady Bird, Tiny Furniture, Ghost World and TV shows like Girls (Weill actually directed an episode of Dunham’s show in 2013) might not exist without the precedents Girlfriends put forth.

Like so many films made before and since, one of the main reasons Girlfriends exists is because Weill wanted to see a film she could actually relate to. “That situation [between Susan and Anne] had happened to me many times by then. My sister got married, my best friend, everybody got married, and I was nowhere in the ballpark,” she told The L Magazine in 2012. “First of all, how do you meet somebody that you like? And second of all, how could you possibly know you want to be with him for the rest of your life? It was so remote a possibility. Also because I was so involved with my work… I was always that ‘other girl.’ So I just started [making] a film about it.”

The generations of filmmakers (and regular women) who came after Girlfriends entered cultural consciousness owe the film—and Weill—a great debt. It was she who elevated their experiences beyond everyday monotony and gave them a new story—their story—to be a part of.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.