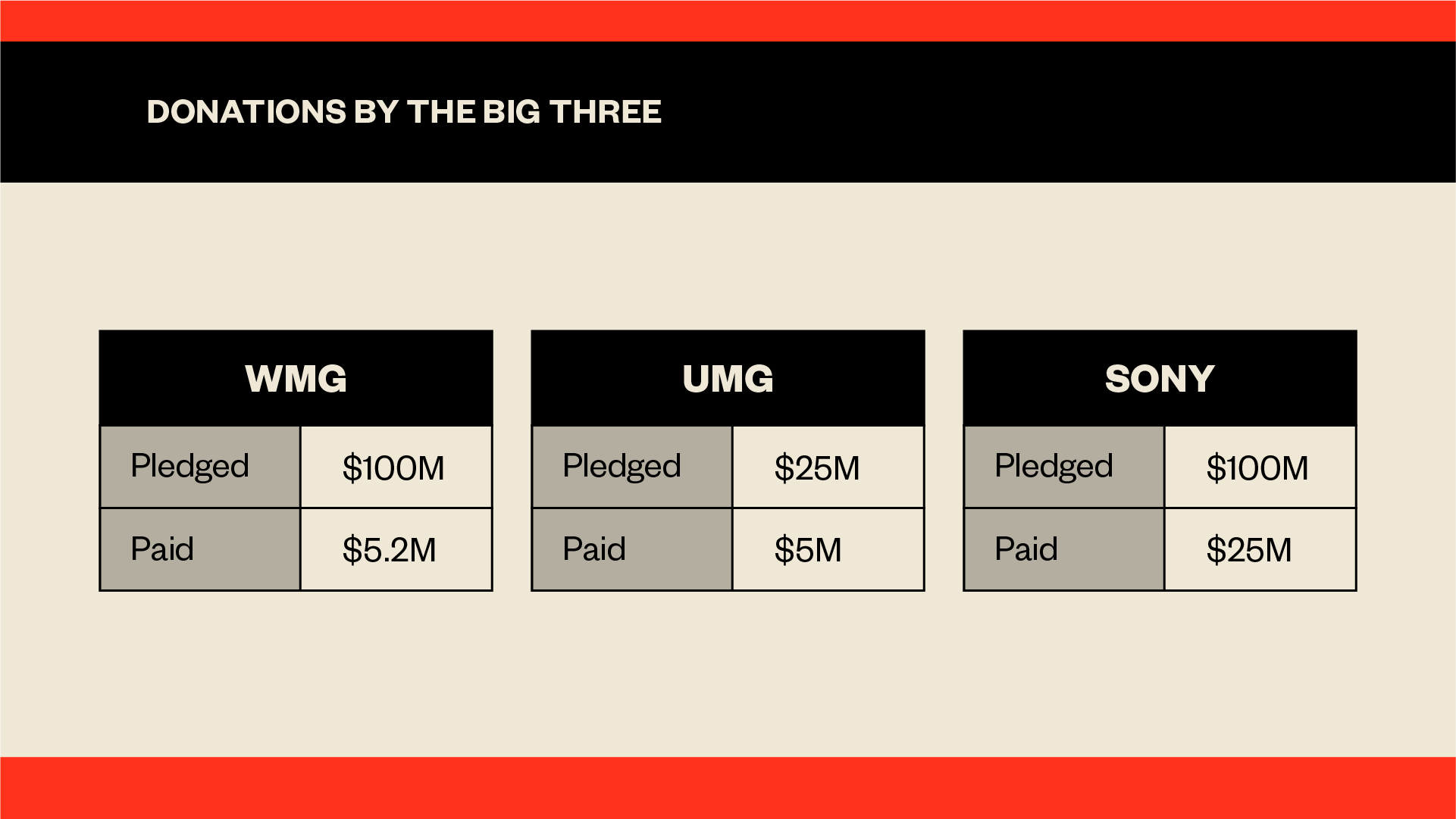

On June 3, 2020, Warner Music Group announced it would donate $100 million to racial and social justice organizations through a newly established “social justice fund.” Within days, Warner’s competitors followed suit: Sony Music Group and Universal Music Group announced they would donate $100 million and $25 million, respectively, through similar funds of their own.

The timing wasn’t a coincidence. The announcements were a direct response to George Floyd’s murder and the crusade for racial justice his death galvanized. At the time, Warner, Sony, and Universal faced intense public pressure to donate to the cause. Each company had put operations on pause for “Blackout Tuesday” and released statements expressing solidarity with the Black community. But Black artists at the “Big Three”—so called because they command 70 percent of the recorded music market share, earning a combined $22 billion in revenue last year alone—demanded they take a step further.

Videos by VICE

When they unveiled their social justice funds, the companies received heaps of positive press coverage. But those stories, and the press releases they were based on, were short on details. Warner and Sony didn’t name a single organization they planned to contribute to; Universal named only a handful. None of them specified when, exactly, the millions of dollars they promised to donate would be awarded.

Nearly one year later, VICE has found, the Big Three have donated just a portion of the money they pledged to give. Warner’s fund has paid out $5.2 million in donations, a representative for the fund told VICE. Universal’s fund has paid out “close to $5 million,” a company representative told VICE. Sony’s fund has paid out $25 million, a company representative told VICE.

Those numbers, which the companies have not previously disclosed, have proved difficult to verify. In an attempt to authenticate them, VICE contacted all 312 charitable organizations Warner, Sony, and Universal have named as grantees. Of those, 51 confirmed that they had received donations. Just 32 divulged how much money they were awarded, making it impossible to confirm the totals company representatives shared with VICE—and revealing how what we know about the Big Three’s charitable giving is limited, almost entirely, to what they’re willing to say about it.

Warner plans to pay out the $100 million it pledged to donate over the span of 10 years, a detail the company didn’t include in its initial announcement but clarified nine months later in a press release. When asked, representatives for Sony and Universal didn’t say how long it would take the companies to donate the entirety of the money they pledged, though they said all of it would ultimately be disbursed. The donations the Big Three have made to date range in size from $10,000 to $1.5 million, according to grant recipients and company representatives.

When a corporation announces it’s donating a large, specific sum of money to a charitable cause, most people assume it will do so soon—that, essentially, “the check is in the mail,” according to David Callahan, the founder and editor of Inside Philanthropy, a digital media outlet that covers charitable giving. By quietly spreading their donations over a span of years, corporations can receive all of the positive publicity and goodwill a high-dollar announcement brings without taking a commensurate hit to their bottom lines.

“They want to put out big numbers in the heat of the moment. But it becomes a much smaller, more manageable expense if it’s drawn out over time,” Callahan told VICE. “You get all the PR benefits without the cost, which is ultimately a big goal of corporate philanthropy: Get the most PR for the biggest number that you can put out. The bigger the number, the better the PR. And then you want to find ways to hit that number with as little real cost as possible.”

Though that practice might be “deceptive,” Callahan said, it’s not uncommon. Any time a corporation pledges a large amount of money to charity, those who work in philanthropy presume it will be donated over a stretch of time—typically between three to five years, Callahan said. From an outsider’s perspective, that might seem self-serving, and to some degree, maybe it is. But according to Callahan, logistically, a corporation needs time to disburse all of the money it promises to give away.

“Practically speaking, it takes a while to get the money out the door,” Callahan said. “If you’re accepting grant applications, you’ve got to set up a process. You’ve got to review the applications. You’ve got to find out who to give it to. To do philanthropy carefully can reasonably require payout over time.”

Those who help run Universal, Warner, and Sony’s social justice funds told VICE there are good reasons they’re making donations over the span of years. According to Towalame Austin, the executive vice president of philanthropy and social impact at Sony Music Group, the issues Sony’s fund is trying to address demand it.

“In philanthropy, we tend to try to solve problems in three to five years. That’s just not the way life works.”

“This issue around social justice is systemic in nature, and we understand that there has to be an ongoing commitment to these issues to impact change,” Austin said. “We’re not going to make change overnight. Sony understands that, and they made that commitment to stick in there and help make change over years.”

Dr. Menna Demessie, who oversees Universal’s social justice fund as the senior vice president and executive director of the company’s Task Force for Meaningful Change, said that speeding up the fund’s grant-making process would be a disservice to the organizations it wants to help.

“If we gave our money away just to say we gave it away, [we could] miss the mark of actually empowering the community,” Demessie said. “Meaningful work takes time. We don’t want anyone to not have a chance to receive funding if they most need it, and they meet our mission.”

Yvonne Moore, who helps Warner’s social justice fund write grant agreements and issue donations as the head of Moore Impact, the fund’s fiscal sponsor, said that for the fund to make a difference in the fight for racial justice, “it can’t just be deploying money.” A spokesperson for the fund added that while Warner may have donated only $5.2 million to date, it has committed more than $12.9 million, meaning the organizations that will receive that money know it’s coming.

“We’re talking about literally generations of racism and systemic racism and power dynamics. This work is very deep, and it has to be thoughtful,” Moore told VICE. “In philanthropy, we tend to try to solve problems in three to five years. That’s just not the way life works. It’s just not the way these kinds of issues and these kinds of challenges work.”

At this point, the Big Three may have only paid out a portion of the money they pledged to donate, but what they have given has made an impact. Sony’s fund has awarded grants to more than 300 organizations, according to a representative for the company. Among them are the Pennsylvania-based Project Libertad, which provides legal representation to immigrant children facing deportation, and HomeFront, which operates a shelter for homeless families in New Jersey and helps them secure affordable housing. Warner’s fund has made donations to six organizations, according to a representative for the fund, and recently named three additional recipients. One Warner grantee, the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, has used Warner’s donation to help more than 40,000 people formerly convicted of a crime become eligible to vote by paying their remaining legal fees and other bills. Another, the Rhythm & Blues Foundation, provides financial and medical assistance to legacy R&B artists impacted by the pandemic. Universal’s fund has donated to more than 100 organizations, according to a company representative, including ESCAPE, a nonprofit working to prevent child abuse in Puerto Rico, and Lotus House Shelter, which accommodates more than 500 women and children at its shelter in Miami each night. The donation to Lotus House, a spokesperson for the nonprofit told VICE, has been “nothing short of life-changing.”

Without question, the donations the Big Three have made to date, along with the millions more in grants they plan to award over the coming years, are significant. But given how much these companies earn, some say the amounts they’ve pledged to racial and social justice aren’t enough.

“All three of these companies could have committed a lot more,” Megan Ming Francis, a political science professor at the University of Washington who studies philanthropy, racial politics, and social movements, among other subjects, told VICE. “What they are committing is such a small slice of the pie.”

In fiscal year 2020, Universal Music Group earned roughly $9 billion in revenue; Sony Music Group earned roughly $8.6 billion in revenue; and Warner Music Group earned roughly $4.46 billion in revenue, according to financial reports from the three companies. The amounts each company says it has donated over the past year—Universal’s $5 million, Sony’s $25 million, and Warner’s $5.2 million—represent .05 percent, .3 percent, and .1 percent of their FY2020 revenues, respectively.

A fairer way to measure the Big Three’s donations, perhaps, would be to compare them to their profits. The companies don’t report their profits according to the same metric, and the reports cited above only include a limited amount of financial information. That said, in fiscal year 2020, Universal Music Group reported an EBITDA—earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization, a rough measure of profits—of about $1.8 billion. The roughly $5 million the company says it has donated to date represents about .3 percent of its FY2020 EBITDA. In the same fiscal year, Warner Music Group reported an adjusted EBITDA of $837 million. The $5.2 million Warner says it has donated to date represents about .6 percent of the company’s adjusted EBITDA in FY2020. Sony Music Group didn’t disclose its EBITDA for fiscal year 2020, but it did report its operating income, another rough measure of profit, at $1.7 billion. The $25 million the company says it has donated to date represents about 1.5 percent of its operating income in FY2020.

“The way that so many companies think about what’s important, and the way in which they measure success, is revenue—is money,” Francis said. “So it’s crucial to think about: How much of that are you willing to put to this other issue, if it really is important? By putting only a slice of the pie toward the issue of racial justice, you’re telling us that it is only marginally important.”

According to representatives for Sony Music Group and Universal Music Group, the money in their social justice funds is derived specifically from their earnings—not the overall earnings of Sony Music’s parent company, Sony Group Corporation, or Universal Music’s parent company, Vivendi. According to a representative for Warner’s social justice fund, a portion of the money in the fund is derived from Warner Music Group’s earnings, and a portion is provided by the Blavatnik Family Foundation, which is self-funded by WMG’s owner, Len Blavatnik. Blavatnik has a net worth of $39.9 billion; his foundation donated $51.4 million to charitable causes in 2018 alone, according to a filing with the IRS. A representative for Warner’s social justice fund wouldn’t say how much money Blavatnik’s foundation contributes to the fund.

When considering the net cost of these companies’ donations, it’s important to note that they can likely use them to reduce their tax bills, according to Phil Hackney, an associate professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law who studies the tax code that governs nonprofits and charitable giving. Under U.S. tax law, corporations that donate to qualifying organizations can take a charitable contribution deduction of up to 10 percent of their taxable income each year. Put simply, that means that if a corporation earns $100 million in taxable income but donates $10 million to charity, it only pays tax on $90 million.

“Part of the story here is that behind those headlines, which get great PR, there’s a lot of fine print. And there’s a total lack of transparency.”

Using a charitable contribution deduction, the Big Three will be able to donate money to charity they otherwise would have had to pay in income taxes, Hackney said. As a result, the net cost of making these donations is effectively smaller than it seems.

“Maybe it costs them 70 cents on the dollar to make a $100 million contribution,” Hackney said. “The government is pitching in, in some part, because they don’t have to pay tax on that money.”

For example: Each year, Warner Music Group has to pay roughly 30 percent of its taxable income to the government—21 percent in federal income tax, and 8.7 percent in state income tax to Delaware, where the company is incorporated. Warner is donating $100 million through its social justice fund. Ordinarily, it would have to pay 30 percent of that—$30 million—to the government in income tax. But by donating $100 million and writing it off as a charitable deduction, Warner avoids paying $30 million in income tax it would have otherwise owed. Though the exact amounts may differ, the same general rule applies to Sony and Universal.

“It doesn’t cost them $100 million to give $100 million,” Hackney said. “They would’ve had to pay $30 million in taxes, state and federal. So they pay $70 million, but $100 million goes to charity.”

One can only speculate about the corporate motivations behind the Big Three’s social justice funds, and how things like positive PR, tax breaks, and net cost may have factored into their decisions to create them. But the motivations of those who actually run the funds seem clear: to provide meaningful aid to organizations that need it, and to benefit the marginalized communities they serve.

Sixteen people sit on the advisory board that oversees Warner’s social justice fund, 12 of whom are people of color. None of them are paid for their work related to the fund, according to a fund representative, and most are company employees. The advisory board has met once a week, every week, since the fund was launched in June, according to Moore, the fund’s fiscal sponsor.

“These folks have full-time jobs. The fund is actually what they’re doing on the side,” Moore said. “Every single time they meet, they’re trying to understand criminal justice better, understand art and activism better, understand the pipeline to prison. How does it actually work? How do you dismantle it?”

Similarly, Sony’s fund is run largely by company employees who volunteered to join the effort and aren’t paid for their work on the fund, according to a company representative. The company appointed employee “task force leaders” around the world to identify organizations in need of funding, according to Austin, Sony Music’s head of philanthropy and social impact. With help from their colleagues, those employees get to make decisions about which organizations, in their own communities, Sony should patronize.

“These are really grassroots organizations, and we’re able to make an even more tremendous impact when you’re funding at those levels,” Austin said. “These are the boots on the ground doing the work in the community.”

Universal’s fund is also run by a “collective” of more than 40 employees who volunteered to join the company’s Task Force for Meaningful Change, most of whom are people of color, according to Demessie, the task force’s executive director. None of them are paid for their work on the fund, according to a representative for Universal. They’ve taken it upon themselves to research potential grantees and ensure that the money in Universal’s fund goes to those who need it most. The same is true of those who administer Sony and Warner’s funds. Overall, the companies have contributed to a wide range of organizations: The three have overlapped on only eight grantees, seven of which received donations from both Universal and Sony, and one of which received donations from all three companies.

“UMG wants to make sure if we’re going to do this, we’re going to put at the center the people who are close to these issues,” Demessie said. “The same people who are calling for change have been put in the position to make that change.”

None of the Big Three had an obligation to allow employees to make decisions about how the money in their social justice funds would be donated, and ultimately, the companies weren’t necessarily forced to create those funds to begin with. One could argue that any amount of money they choose to donate toward social justice—regardless of how long it takes them to pay it out, or how small of a percentage of their profits it may represent—deserves unqualified praise, considering they didn’t have to donate anything at all.

But donating nothing to social justice organizations wasn’t a realistic option for these companies, according to Callahan, the Inside Philanthropy editor. The amount of pressure they faced to do so in the wake of George Floyd’s murder—both from the public, and from artists and employees who work with them—made it a near necessity.

“The American public increasingly sees corporations as moral actors with moral responsibilities,” Callahan said. “The penalties for corporations being out of step with public sentiment on high-profile social or political issues can be high. Music companies in particular, whose demographics—of both their labor force and their consumers—skew very young, and thus, by extension, more diverse, I would imagine that they would feel that heat even more.”

The Big Three have received an incalculable amount of positive publicity from their social justice funds—and to some degree, rightly so. But the PR windfall they’ve enjoyed is based, at least in part, on the sheer size of the amount of money they promised to donate. Nearly every headline written about the companies’ social justice funds includes the figures attached to them, whether it be $100 million or $25 million. When they launched the funds, none of them explained it would take them years to administer the money they pledged to donate. Even now, only Warner has provided an exact time frame over which it will disburse its fund entirely.

“Part of the story here is that behind those headlines, which get great PR, there’s a lot of fine print. And there’s a total lack of transparency,” Callahan said. “It’s hard to know what’s going on, and to the extent that these actors are acting in good faith, and do really plan to give away the money, there could be legitimate reasons to go slowly. But the bottom line is that what the public thinks is happening—the check is in the mail—is definitely not happening.”

“On the other hand,” Callahan added, “if the money really does get paid out, it’s still $100 million.”

Jasper Craven contributed reporting to this story.

Follow Drew Schwartz on Twitter.