Photographers Sunil Gupta and Charan Singh met at an HIV conference in Delhi in 2009. Both had been a part of India’s queer scene for years. Gupta had been photographing LGBT Indians since the 1980s, and had recently moved back to Delhi from London. Singh had worked to build a network of public health educators for working-class queer men in Delhi. Immediately, the two began talking about ways to interact with and capture what it is like to be queer in India.

In many ways, the country has transformed rapidly. Gay men and women are increasingly coming out and not marrying, according to the two photographers. But queer culture is still secretive and being LGBT in India can be dangerous.

Videos by VICE

So when Gupta and Singh were asked by the New Press to put together a book showing the ways India’s LGBT scene had evolved over the years, they knew they’d be in for a big challenge. Not only is it hard to gain the trust of Indians’LGBT community and navigate secretive queer spaces, it’s also hard to translate those spaces into something readable to a global audience without glossing over the thins that make India special. But in Delhi: Communities of Belonging, the duo have managed to paint an intimate portrait of Delhi’s queer scene that still feels universal. Through photos and text, the book follows several queer Indians as they navigate their daily lives, such as closeted men with wives and children who go cruising in secret, and openly gay couples who fear that one day they will be persecuted for their relationship.

VICE spoke with the two authors about how they approached the process of documenting LGBTQ Indians, and how the queer community has changed over the years with increasing globalization.

Zahid and Ranjan are among the few openly gay couples in Delhi. “Even though people are more out today, there is that thing in the back of the mind saying this is still illegal in this country. If they decide to crack down on it, we are too exposed already, so we would be in a lot of trouble,” says Ranjan.

VICE: How long have you been photographing the LGBT community in India?

Charan Singh: I’ve been working on this since 2011, I suppose, but before that I was working with HIV NGOs in India. I was primarily working with the lower and middle class groups, then at some point I felt that I needed to do something else with it, with my work, with the kind of community activism I was doing. I felt that photography is the way to tell these stories. I took up photography as a medium.

Sunil Gupta: I’ve been shooting the LGBT community in India since the 1980s. I left India in 1969, the Stonewall riot summer, to live in Canada as a migrant. Within a year, I realized this Indian identity that I’d brought with me had virtually no value as a teenager. Then, this homosexual activity that I’d also brought with me suddenly had a name, “gay,” and it suddenly had a voice and a presence. And so I became a fashionable young gay liberation activist at a very early age.

After a little while, it occurred to me that I wanted to know if similar things were happening in India. The 70s was the period in the West where I got assimilated into a gay politics, which made me curious about what the gay politics of India might be. I’d never lived there as an adult. I didn’t know what it was like speaking to [queer] people there. I’d only lived there as a teenager, which meant it was all about sex, not about speaking. When I got an opportunity to go [back to India] in 1980 to shoot something different, I thought I’d do some personal research into this. That’s how it was for a few years. I would get work to shoot in India, and then I’d do some private research into what gay life was like. When I got there, I was relying on a combination of going to cruising sites, and also relying on a social network of gay men that I’d encountered, which I found was very efficient in terms of passing me on from person to person.

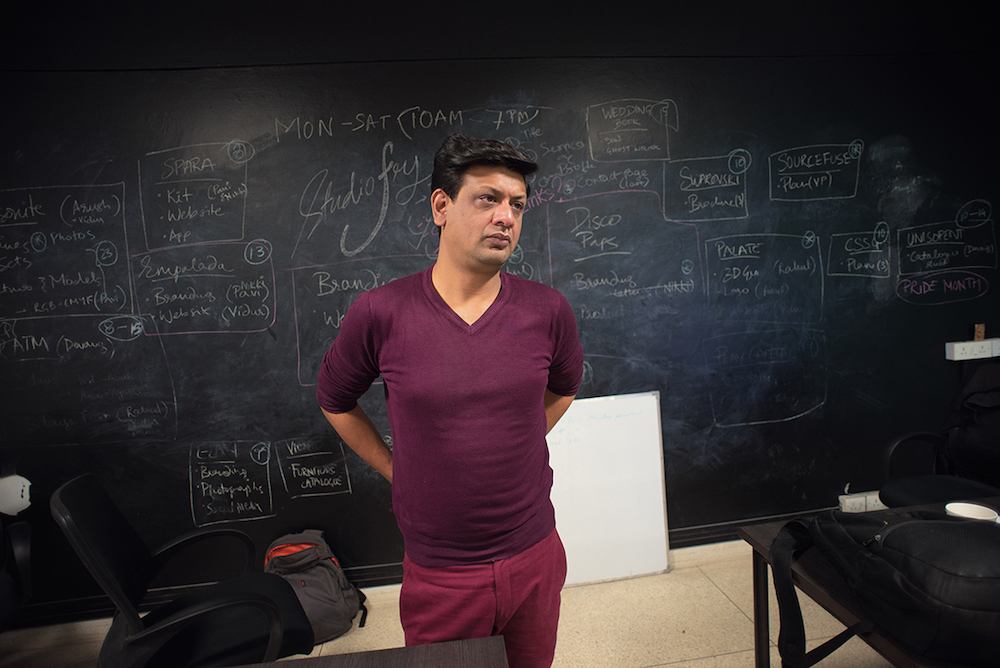

Pavitr, a graphic designer, comes from an affluent family. An activist in the LGBT movement, he shares a flat with another man and is single with a busy social life. “My family didn’t hassle me after I came out. From then on there was no marriage pressure,” he says.

Can you describe how the LGBT scene has evolved since then?

Sunil Gupta: What I found was that I lost the ability to distinguish who was gay. I think that’s culturally determined. It’s like when I first went to Canada, I thought everybody was straight. I couldn’t tell. When I went back to India ten years later, I reversed that: Everybody seem to be gay because they all walked in hand in hand. They all were limp-wristed. It’s so cultural, but no one wanted to talk about it. That put people off. In a cruising area, for example, people came to have sex, not to have a chat about it. I was trying to collect audio interviews as well as photographs, for artistic purposes. I guess I looked like some kind of social scientist with a tape recorder and a camera, and people were not keen to speak, and they were definitely not keen to be in a picture. Everybody was in the closet still, and I thought it would be very unfair to publicize them all over the world without their knowledge.

Today, many are still not out, but it’s hugely different in terms of documentary and photography. In 1980, nobody would turn their face to my camera and people certainly did not want to have their name on the picture, which they do in the book. The project now, which is portraits of real people with their names, with them facing the camera, is completely a reversal from how it was then. That’s how I experienced it photographically.

Charan Singh: To add to what Sunil said about how the scene has changed or really hasn’t changed: Gay men are all still married. Back in the 1980, when I was taking the pictures meeting these people at the parks, they were claiming to be gay, and I used to say, “Well, you’re not gay because you’re married with five children.” They’re not gay in the sense that the West knows—that you walked of your house, left your biological family home, and didn’t get married to the opposite sex and had children. That’s a huge social pressure and norm in India, and it’s still there [today].

Jatin (right) belongs to a community of Dalits (“untouchtables”) and identifies as a kothi (a term for an effeminate man). He was forced to get married, and lives with his wife and three children in his parents’ home. He seeks out male sexual partners in the park on his way home.

What about the trans community in India?

Charan Singh: There was a subgroup of men who were calling themselves kothis, who were more feminine and equivalent to street queens who would sometimes dress up. Sometimes they’re also involved in sex work. There are trans people, who we called hijras (which has a whole mythology around it), and there’s a big family-like structure, which has been more well-documented in India.

Sunil Gupta: What we think of as “trans” [in the West] is relatively recent. But in India, hijras is an ancient idea. It’s been a living culture for hundreds of years. Indians grow up with it. We all grew up looking at them on the streets and being familiar with it. The word “trans” doesn’t quite get the nuances of India, and its range of people.

For more on queer culture in India, watch the GAYCATION doc ‘Hijras, the Third Gender in India.’

That brings up a point I know you grappled with a lot: How do you make this book and your work relevant and relatable to Western audiences without glossing over the differences in how we view sexuality and gender here versus in India?

Sunil Gupta: My interest in this whole project was to locate images of actual Indian LGBT people in art history. I had no previous history or reference to turn to. All my references were European or American. That’s changed over the last three decades. I’m hoping that the reception of this book will be more widespread than my pictures in the 80s. I think when I showed my pictures in the 80s in London, they seemed very niche. They seemed exotic and foreign. I don’t think people were that interested to even try to figure out what was going on. It just seemed too far away, too exotic, too other. I think now we live a in more globalized world.

Charan Singh: I think that’s the whole debate, and also what we’re trying to do with the book. We were trying to look at the range of people who are accepting their sexuality differently. Also, from different classes, so their entry points are also way different. Some of them are activists, some of them are academics, some are sex workers, some of them are just there and a part of their community.

I know most of the people in my pictures, and I’ve known them for quite a long time. I grew up with them. There is this whole idea about when you’re growing up as a child or like a young person, and you always think about your family and those kind of relations. Then in this community of [queer] men—the men I was talking to, the kothis and thehijras—they’ve adapted to the same culture, the same familial ideas [with each other]. One of the very crucial things is also [queer people’s desire] to get married, but there’s no legal status for marriages between hijras and others, even though some still have partners and they live together. Sometimes the partnership goes for lifetime.

Geeta (let) comes from a wealthy family in Mumbai and only felt comfortable coming out in the United States. She lives part of the year in India, and the rest of the year with her American wife Kath in Virginia. “It matters to me that I’m in India. Sometimes it’s hard to be here… I feel like danger is stalking us in a much more different way,” she says.

And what about lesbian communities in India?

Sunil Gupta: In the 80s, when I was finding that men had no speech about [being queer] and they were voiceless or in the closet, but were able to have a lot of public sex, women had a relatively opposite experience. Streets [in India] can be dangerous to women, so they’re not hanging out on the street corners, and so women did have a voice. Privately, women were talking a lot more about a women’s movement, in which there’s space for sexual difference. Some of India’s more recent gay liberation and the politics of it from the 90s, early 2000s, emerged from the women’s movement.

In what direction do you see the future of LGBT life in India going?

Sunil Gupta: The older people are all married and in the closet, and they’re never going to come out. They’re still completely invisible. I think the [younger] generation is keen to be liberated. India is growing rapidly, and younger people are well-off; they all have jobs. They want what they want, and they want it now. They don’t want to wait for some later time to be freed, so they’re much more demanding of their rights.

My theory is that gay liberation was born in rich Western places like New York and London because it takes money. You can’t be poor and liberated. To be out and leave your family requires that you either have cash or you live in a welfare state like Europe. If you leave your family in India, you’ll starve, and there’s no healthcare, there’s no housing. There’s nothing. You can’t leave them, so it’s very difficult to be outwardly, like, “I’m a single gay man in my own apartment.” That doesn’t work. You don’t have the means for that in India.

Charan Singh: In India, you grow up with this idea that beyond your blood family, there’s no existence of your own. I think you give so much of yourself to the family that you don’t think about life beyond that structure. I think it’s now slightly shifting where people are moving out, with internal migration from different cities within the country. Also going abroad and coming back, and all of that. I think it’s making space for different kinds of voices.

‘Delhi: Communities of Belonging’ is out now via the New Press. Order the photo book here.

Follow Peter on Twitter.