All photos by the author

The southern Asian nation of Burma, also known as Myanmar, has a welcoming and friendly nature contrasted by a dark, criminal underbelly. It’s a regular destination for wealthy families on packaged bus tours and backpackers, and yet it’s fighting numerous ethnic armies on multiple fronts, is the third largest producer of opium in the world, and one of the most dangerous places on the planet for ethnic and religious minorities outside of the territories held by the Islamic State.

I first visited Burma in 2010, when the country’s beloved opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi was being released after 15 sporadic years of house arrest. On my third day in Burma, I found myself staring at Aung San Suu Kyi as she addressed a crowd of no less than 10,000 die-hard supporters who were crying, screaming, and fainting. I saw genuine hope and happiness in the their eyes—it was a beautiful thing to witness and I wanted to tell this story of a democratic transition for this country. However, things didn’t go quite as planned.

Videos by VICE

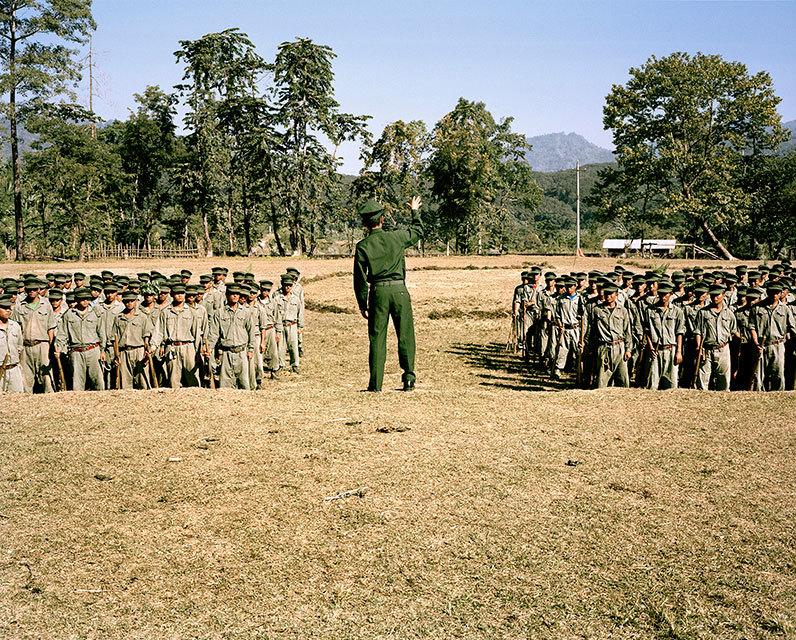

Shan army soldiers

As I got further into the story, I realized that Burma’s “transition” is a volume of smaller stories that must first be looked at and understood before one can actually comprehend modern Burma’s state of affairs. This is why I named my book Little Pieces; this is only a small piece of the puzzle that is Burma.

I wanted to focus on Burma’s ethnic civil war after hearing stories of attempted extermination at the hands of government forces and other atrocities from refugees along the country’s eastern border. There are a total of 17 government recognized opposition armies active within Burma. This all stemmed from an agreement between the various ethnic groups and the government in 1947 called the Panglong Agreement that was never recognized by the military after Aung San (the author of the agreement and the president at the time) was assassinated. The agreement laid out a road to autonomy for the ethnic states once held together by the British Empire. Since 1947 over 30 different ethnic armies have fought the Burmese military for autonomy on some scale, so I decided to focus on the three most active armies: the Kachin, Karen, and the Shan.

The Kachin army

This conflict has been grinding along for six decades, making it hard for it to get coverage in the mainstream media unless an untold tragedy happens. Each ethnic group has such a diverse and unique history I felt the story warranted a full book. Looking back at the shots I cut out, I could have made three volumes. These images try to tell the story of the struggle faced by ethnic minorities living within the Burmese apparatus of oppression.

Because Burma is still an obscure country for a North American audience, I decided to release my book at a point when people might be talking about Burma. On November 9, Burma held its first national democratic election in 25 years. With the country’s main opposition party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), winning a house majority, Burma looked distinctly like a newly blossomed democracy. But looks can be deceiving.

A soldier from the Karen army

There is one Achilles heel to Burmese democracy that the military has expertly put in place to consolidate their power over the populace: the 2008 constitution.

In 2003, in a bid to change the government’s international reputation as an oppressive military dictatorship, state media announced the Seven Step roadmap to democracy. The steps included reassembling the National Convention and holding free and fair elections. However, the most significant step was to draft a new national constitution, and the government at the time knew precisely what it was doing. Changing one general for another went poorly in the past, so the government and military got smart and made a constitution that gave them ultimate control from behind the scenes.

In 2008 the new national constitution was drafted by the government, which set out clearly defined parameters for keeping the military in key power positions indefinitely. The 2008 constitution guarantees 25 percent of parliament’s seats be designated to the military while any amendments to said constitution requires over 75 percent approval of parliament. Furthermore there is a committee called the National Defense and Security Council comprised of over 50 percent military personnel that have the ability to veto any decision and happen to wield more constitutional power than the elected government. To make matters worse for government opposition in the country, there is a special clause that many believe to be solely directed at keeping Aung San Suu Kyi from power, which states you are ineligible to run for the presidency if you have children who are foreign citizens. Since Aung San Suu Kyi married Michael Aris, a British citizen, in 1972 and had two children with him who also subsequently hold British citizenship, she is barred from running for president.

Another Karen army soldier

On top of all of this, the military was granted unimaginable powers such as selecting the defense minister, the border affairs minister, and the home affairs minister while key departments such as the judiciary and police are beyond reach of the elected government’s authority. The military even gets to set its own budget that the government has no say in, which gives the armed forces full independence from any elected government.

The first time I visited the country it was illegal to wear or advertise your support for the NLD, Aung San Suu Kyi, or any other government opposition group. Today it is hard to look anywhere in the cities of Burma and not see an NLD flag or portrait of its beloved leader.

To say that Burma’s national elections will change nothing is a false statement. The amount of change, however, is up for debate.

You can find Little Pieces on Bryan’s website.