The first photographic portrait ever made was a self-portrait: a daguerreotype shot in 1839 by Robert Cornelius, who held still for over a minute as the exposure slow-burned into place. As culture and technology have evolved, naturally, so has the practice of photographing one’s self. Since then, countless photographers from Claude Cahun to Paul Mpagi Sepuya and Talia Chetrit have used it as conceptual exercises and expressions of their identity, as well as to discuss a range of cultural and political issues.

And then came the selfie, the 2013 Oxford English Dictionary Word of the Year, which has been equally praised as an empowering cultural exclamation and hated-upon as a dumbed-down vanity exercise. At times, it’s spawned debates about the future of self-portraiture—an on-the-nose question akin to “is painting dead?” “did the Brownie camera kill photography for the masters?” or even “Did Instagram kill photography?”—to which many could rightfully respond: “Yeah, so what?”

Videos by VICE

While it’s undeniable that selfies have forever altered contemporary culture, they are one piece of a long, splintering technological and photo historical puzzle. Selfie or not, self-portraiture continues to evolve. Below are seven photographers who continue to move the genre along. Some, like Tim Davis, directly reference absurdity of selfie tropes. Others, like Angela Cappetta, have been making photographs that resemble the selfie-aesthetic before selfies were even a thing. Still others, like Rafael Soldi, Tommy Kha, Stacey Tyrell, Pixy Liao, and D’Angelo Lovell Williams, use it to examine gender, sexuality and/or the experience of feeling like an outsider.

Tommy Kha

Through performative self-portraits, photos of Elvis cutouts, portraits with his mom, Memphis ephemera, and even video, Tommy Kha uses humor to reconcile his sense of displacement as a gay man of Chinese Vietnamese descent who grew up in a homogenous, racist South.

“Through the lack of seeing my representation reflected growing up in the South,” says Kha, “I try to echo that absence in my work.” Kha started making self-portraits when he moved to New York City in 2010 when his regular sitters were no longer available to pose for him. This early work— which Kha continues to this day—was a series called Return to Sender, in which Kha stands awkwardly, almost like a digital stand-in, while different men and women kiss and embrace him.

Kha’s discomfort and chameleonic identity take on different forms across multiple series—a jigsaw puzzle with only a third of his face assembled, a stack of photocopies of him equal to his weight, life-size cutouts haphazardly placed in a Southern landscape. “I find my photographic self constantly changing forms,” says Kha, “which I find more accurate to our own complex identities.”

Branching into video, in Awkward Film Series (in collaboration with Jonathan Myers), Tommy inserts himself awkwardly into popular movies. In one of the most hilarious vignettes, Kha combines footage from Titanic of Leonardo DiCaprio drawing Kate Winslett, but replaces the actress’s character with nude footage of himself as DiCaprio’s muse.

Kha’s ability to address serious issues with playful, lighthearted irony is sharp and refreshing, and it provides wide-reaching access points often hard to tackle in today’s increasingly contentious culture. “There is a sense of freedom in video,” he says. “That allows my photographic body room to play, though how much [of that playfulness] I like to replicate in my still work remains to be seen.”

D’Angelo Lovell Williams

D’Angelo Lovell Williams makes self-portraits that, like Tommy Kha, respond to his feeling of absence in popular culture and visual history. He’s been photographing himself since high school—wild, Avatar-referencing digitally manipulated snapshots of D’Angelo and his friends—but his formal engagement with the genre began a few years ago when he was working on his MFA at Syracuse University.

“My images are visual narratives as much as they are autobiographies.,” Williams says. While “biographical” might imply a clear-cut set of personal facts, Williams’s work communicates a personal history that’s a bit blurrier and less easy to define. His photographs, sometimes made solo, sometimes with other men, are formal and direct, and they encourage a slowed-down approach to looking and being seen. Many of his photos use the body as a sculptural tool for self-reflection.

In one image, A Day Apart, 2018, collaborator Clifford Prince King, smoking a cigarette with a stern sense of cool, wears a white dress that conceals Williams sitting naked before him. Warm, magic-hour light spotlights the couple’s mysterious amalgamation, while the protagonist stares back at anyone daring to look, owning their gaze.

In another image, Hieroglyph 1, 2018, Williams and another man stand back to back, naked in a grass field, holding hands, butts touching. Like A Day Apart, while their relationship is ambiguous, their performance, pose, and direct, almost defiant gaze back at the camera suggests a sense of personal reclamation and agency. For Williams, these photographs are a means of amplifying “who will not be seen, have a voice, have resources, or live a life that so many black people and people of color don’t get to live out loud.”

Making self-portraits with other men expands the narrative beyond his own. “There are certain images I can make alone,” says Williams, “but there are certain ideas that involve other people that I can’t make alone or might not want to be in.”

Tim Davis

While on sabbatical in Indonesia with his family, Tim Davis began South Seas Selfies, a departure from his more widely known formal, brooding social documentary photographs of the American landscape. In these photos, Davis playfully recreates vacation selfies—cheesy images you might see on a photo slideshow, with self-aware jabs at how Westerners behave (often disrespectfully)— while vacationing in developing countries.

“I’m mostly horrified at how centered on ourselves photography has become,” says Davis. “That being said, the camera is like a golden retriever and the world is a tennis ball, meaning it’s an uncritical tool without our guidance, and in a desperately foreign environment I found it hard to say much about the world around me.”

Uncomfortable making photographs of a culture he knew nothing about, he turned the camera on himself. In one picture, Davis’s head juts into the bottom of the frame, backlit by a beach sunrise that reflects off his camera, spotlighting his eye. In another, his hand holds a printed snapshot of his family posing for the camera. It’s the kind of photo one nervously asks a stranger in a strange land to take again and again—Davis and his wife smiling while his son stares off, missing the “smile” cue.

And, in another, Davis’s eye peers through a hole cut in a lotus leaf—appearing almost superimposed. “Making the work became a way of navigating these new spaces,” he says, “always acknowledging my presence and role as a dumb tourist.”

Stacey Tyrell

Stacey Tyrell’s self-portraits respond to her identity as an Afro-Caribbean Canadian with European heritage. In her series Backra Bluid, taking its name from a hybrid of Afro-Caribbean slang—backra, meaning “white master,” and bluid, the Scottish word for “blood”—the artist dresses up as various female archetypes and lightens her skin to appear white.

She titles the images with a made-up name and ages that somehow feel tied to who we think each woman might be. Ertha, 44 Years, for example, wears a luxurious fur coat and expensive-looking earrings. She’s a character you might have seen in a TV show like LA Law, a mid-90s soap opera or a Tina Barney photograph. Wealthy, extravagant, but a little out of place. Or Bonnie, 35yrs. and Twins Lara & Maisie, 9yrs—a mother and twins dressed in prep school regalia and photographed in front of a nondescript background—or Ailis, 21yrs. (2012), who poses with her tennis racket and other signs of wealth in front of a wood wall.

The women in each of these photos confront viewers with distant, emotionless stares that, exaggerated by the digital tools used to lighten their skin, feel conscious and almost sci-fi. Tyrell isn’t trying to fool viewers, but instead, creates a sense of questioning or unease. While each woman has a nearly identical lightened skin tone, their non-European features vary. Perhaps they are “passing” as white, inspiring an additional layer of questioning for viewers.

This work reflects Tyrell’s experience growing up attending predominantly white schools, and receiving strange, inquiring stares when she mentioned her European heritage. Backra Bluid was not only an opportunity to confront a racist glare but to imagine what her white relatives may have looked like, as well as her own perceptions of white identity. “It allows me to step outside of myself for a bit,” Tyrell says, “by donning a costume and trying on a gaze that I never experience in my actual life.”

In one of her latest photos—published for the first time here in VICE—Tyrell presents two photoshopped versions of herself. In one, she’s dressed in the 1700s Georgian style, whitened skin, with an elaborate hairstyle popular among the aristocracy of the time. On the other is Tyrell as a black woman holding a papaya, a vague allusion to Caribbean slang for vagina. “I’m trying to convey,” says Tyrell, “the way that both white and black femininity have been intertwined and codependent of one another in a historical and colonial context.” Across all of Tyrell’s work, self-portraiture is a tool for figuring out larger ideas and potential universal truths about the construction of identity, Western history, and to “ flesh out ideas with no one watching.”

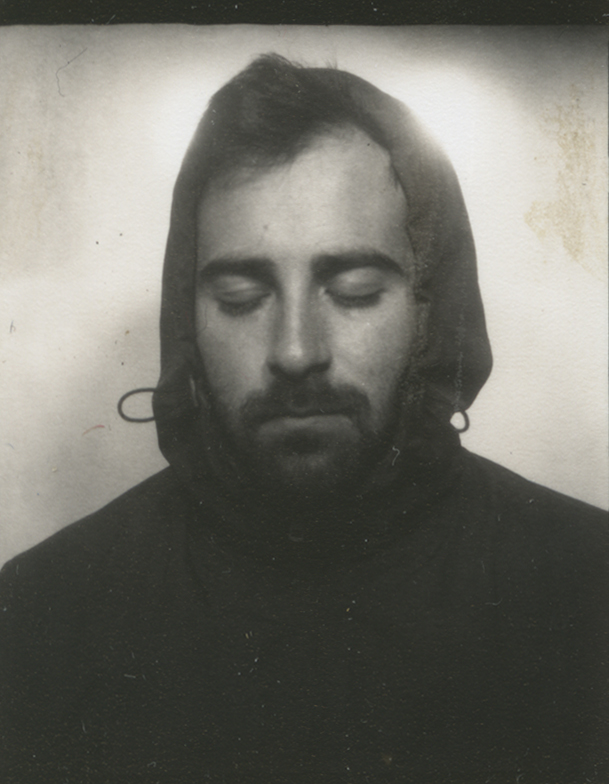

Rafael Soldi

Rafael Soldi hates photographing himself. When asked if it helped him figure things out about his identity, he responded, “It forces me to face the questions I’m often too scared to ask myself.” Whether or not he is physically present in his photographs, it’s not far fetched to consider his larger artistic practice to be one spanning self-portrait.

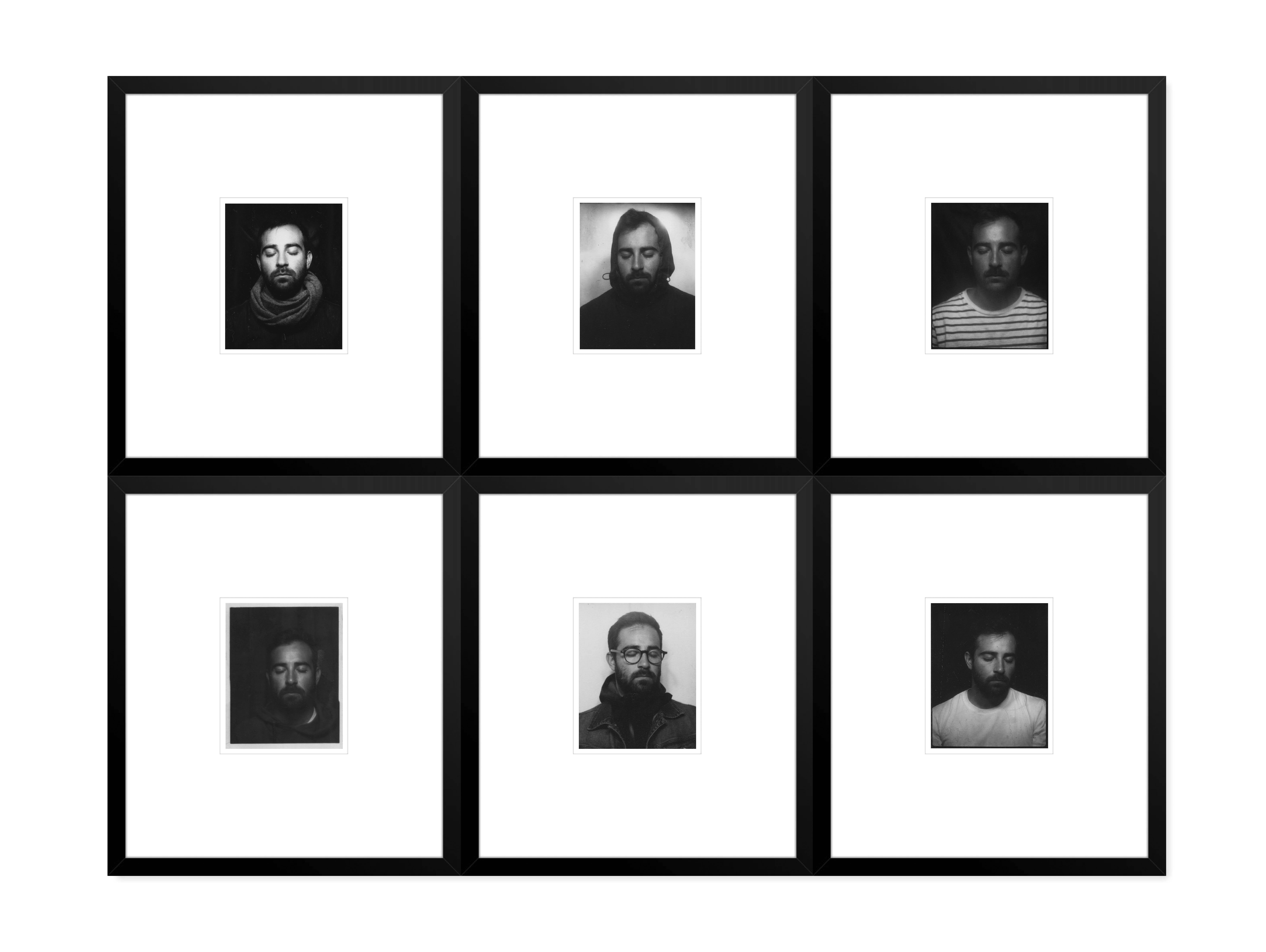

His series Life Stand Still Here, which began several years ago as a response to a devastating romantic breakup, has shifted into a more ambiguous, darker reflection of personal and cultural discomfort. This ranges from monochromatic almost-black photographs of water to a 14-foot installation of 50 near-identical photo-booth self-portraits. The series is a metaphor for grief and loss, whether it’s more literal—his breakup—or something more nuanced—the potential loss of culture as a Peruvian-born immigrant who’s lived in the United Stages for more than 15 years.

For Soldi, the passport-size photo-booth portraits, all made with his eyes closed, pose the question “how do we grieve the life we left behind in order to live this one?” His body serves as a spiritual stand-in for other immigrants shedding their histories, which he describes as “imagined futures,” meditating on what they may have left behind. “The photo booth,” he says, “acts as an apparatus that contains the entirety of my body, a small stage for a monumental performance both private and public all at once, captured once, one of a kind.”

Pixy Liao

Growing up, Pixy Liao’s notion of love was being with someone older than her—a mentor she would look up to, someone with some level of power over her. When she came to the United States from China to study photography and began dating someone five years younger, her understanding of this dynamic broke apart. In 2007, she began Experimental Relationship to respond to it.

Experimental Relationship depicts Liao and her partner, Moro, performing a series of funny, contrived gestures. In one image, Moro massages Liao’s shoulders as they both stare directly into the camera. In others, Liao lays across Moro’s back, almost pointlessly, like planking, T-bowing, or other internet memes, wearing him like a disposable garment. In another, Liao, who is significantly shorter than Moro, picks him up, flinging him over her shoulders, about to carry him away.

Liao’s photos present a loose role-reversal, poking fun at power structures through their absurdity, often flipping, repeating, and jabbing at clichés from popular media and art history. A nipple grab, a hushing index finger, a woman consoling her lover—each humorously commenting on the complexities of their relationship as well as larger stereotypes about heterosexual dynamics.

These portraits are a way of “trying on” the prescribed roles and behaviors for romantic interaction. The camera’s cable release is often visible to viewers, almost always held by Moro, which Liao suggests is a hint at some power she’s giving back to him. “It looks like I’m sending a signal to him to take the photo,” says Liao. “I think it’s like a metaphor for our relationship. Sometimes, the one who seems to be in control is actually the one who is being controlled. Also I think it’s important to give him some control in the photos.”

Angela Cappetta

For years, between commercial shoots and documentary projects, Angela Cappetta has photographed on the fly, grabbing in-between moments with New York City’s chaotic landscape as her backdrop. On a bus, in a cab, somewhere where the available light is convenient and works, Cappetta makes self-portraits wherever she is. “I always shoot cars,” Cappetta says. “I will always shoot an interior. And then I always shoot myself. It’s not very complicated, and it’s always something available to shoot.”

Many of Cappetta’s photos, which, until recently were all shot on film, look like precursors to selfies. She stares at the viewer, inches from the lens, confident, yet unsure of how she’ll come out. While she may have been able to shoot multiple frames, there’s no screen to trigger a “take it again” response. There’s always an element of anticipation or surprise, often another person sharing Cappetta’s gaze back at the camera. A man on a bus, a mother and child walking behind her on the street, a game of chance that might read differently in today’s iPhone-heavy culture.

In other photographs, shot in a mirror or other reflective surface, Cappetta’s camera is visible, front and center. But these photos are different than the posturing avatar-style photos of bro-photographers boasting their wares we’ve come to expect—instead they fit into a larger diary of Cappetta’s in-between moments. Pauses getting from here to there.

And still, other, slightly more formal images show Cappetta in more personal spaces—in her apartment, in bed, on a couch, all spaces that are her own, sometimes staring back at the lens, sometimes off in thought. Regardless of the environment and where she directs her gaze, Cappetta’s self-portraits which she continues making to this day, capture a sense of confidence and self-possession—she is in control of her likeness, whether it’s glamorous, fleeting, or somewhere in between.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Jon Feinstein on Instagram.