The Shenandoah Valley Juvenile Center is tucked away on a dead-end road in rural Virginia, just off a highway named for a Confederate general. It has a beige-brick exterior and a green roof, and from the outside it doesn’t look especially intimidating. There’s no barbed wire or fencing around the perimeter, but inside it’s a juvenile jail housing several dozen boys and girls, including some as young as 10.

When J.Z., a 17-year-old immigrant from El Salvador, arrived there last summer, he didn’t know what to expect. The Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials escorting him hadn’t told him where they were taking him, or exactly why he was being detained. He’d been arrested for trespassing at his Long Island high school (a charge that was later dismissed) and spent about a month in a local jail before the federal agents came to pick him up and put him on a plane to Virginia.

Videos by VICE

He knew his situation had something to do with his immigration status, but he thought it was a misunderstanding and things would sort themselves out. Now he wasn’t so sure.

“When I first saw that building, I was afraid,” he recalls. “I was like, what am I doing here? I’m not a criminal.”

Inside, he was first ordered to shower, then questioned and assigned to the Delta wing of the jail, which is reserved for kids with good behavior — Alpha was reserved for the troublemakers. But he still couldn’t get any answers. About a week passed before he was allowed to make a phone call to his mom. The staff would only tell him that he was “un peligro para la comunidad” — a danger to the community. It soon became clear they suspected he was involved with MS-13.

“They were always asking me, ‘When did you start with the gang? Do you have tattoos?’ Everything,” he said. “Always trying to have any evidence contra ti.”

J.Z. ended up spending the next month at Shenandoah before he was transferred to a lower-security facility also operated by the Office of Refugee Resettlement, or ORR, the federal agency that’s responsible for the custody of immigrant kids. He says staff taunted him about facing deportation and constantly pressed him to confess to gang membership, which he refused to do. Altogether he was locked up for nearly six months, with little contact with his family.

President Trump’s decision to separate immigrant children from their parents at the border and place them in cages has led to widespread outrage, and the move led to some 2,000 children entering ORR custody in just a few weeks. But J.Z.’s case — and dozens like it — reveal how the Trump administration had already been using ORR facilities to detain immigrant youth, alone and without due process, for months at a time.

ORR’s shelters, treatment centers, and jail-like “secure” facilities like Shenandoah, where J.Z. was held, have been transformed into a de facto juvenile detention wing of the Department of Homeland Security, housing thousands of kids. Most are unaccompanied minors seeking asylum in the U.S. and just a small fraction are charged with any crimes. ORR has the authority to detain these children indefinitely.

ORR did not respond to questions about the agency’s role in detaining immigrant youth on behalf of the Department of Homeland Security. A spokesperson said the agency determines where to hold kids based on information from other federal agencies and that its secure detention policies are intended to “strengthen safeguards” for ORR facilities and communities where kids are placed with sponsors or relatives.

ORR’s founding mission is humanitarian: It’s in charge of helping to resettle refugees, and it has been tasked for more than a decade with caring for kids who arrive alone at the border. But under Trump, its role as a jailer has expanded.

“ORR is not a law enforcement agency,” said Bob Carey, who was the agency’s director under President Obama. “It’s a health and human services agency. It’s not really equipped and the staff isn’t trained to make law enforcement decisions, nor was it envisioned as a juvenile detention provider.”

Federal law and a 1997 settlement known as the Flores agreement require the government to release immigrant kids from detention within 72 hours or keep them in the least restrictive setting possible, which has come to mean licensed child care facilities funded and monitored by ORR. ORR maintains that most kids spend only a few weeks in custody, usually in low-security shelters, before they are released to parents or sponsors. But under Trump, immigrant children are being held for longer periods of time. In October, an agency spokesman said the average length of detention was 38 days. By June, that time had increased to 49 days. Now it’s up to 56 days. For some kids, it can be much longer. A lawsuit filed by the ACLU of New York identified 45 kids who have been detained for an average of eight months.

Conditions inside ORR facilities, especially the restrictive ones, can be horrific. An ongoing class-action lawsuit claims that staff and guards at Shenandoah stripped kids as young as 14 of their clothes and strapped them to chairs with bags placed over their heads. In another case, ORR has been accused of placing kids in mental institutions and forcibly injecting them with drugs without permission from parents. (ORR denies the allegations of abuse and says it acts in compliance with state child welfare laws.)

Holly Cooper, one of the lead attorneys on the Flores case, said holding kids in ORR detention is intended to coerce them into accepting deportation as a way to end their confinement. Recently, kids separated from parents at the border have reportedly been pressed to accept “voluntary departure” as a way to reunite with their mothers and fathers.

“You put a human being in a cage, they want to get out of the cage,” said Cooper, co-director of the Immigration Law Clinic at the UC Davis School of Law. “If that’s accepting a plea bargain or deportation, people will make that choice, even if it’s not in their best interest.”

Nearly three dozen other kids found themselves in a situation like J.Z.’s after they were picked up during a pair of anti-gang sweeps on Long Island last year. Some were shipped across the country to another ORR-contracted jail in Yolo County, California. In August, the ACLU of Northern California filed a class-action lawsuit on their behalf, alleging that the detentions were unconstitutional and based on flimsy evidence. In 30 of 35 cases, including J.Z.’s, judges ruled there was no cause for them to be detained, though they are still facing deportation.

J.Z. asked for his full name to be withheld due to fears of reprisal at his school and from immigration officials. He said that part of the reason he wanted to leave El Salvador for the United States was that he believed it was a country that wouldn’t put innocent people behind bars. He agreed to tell his story because he doesn’t want others to relive his experience.

“I don’t want to have this happen with another kid,” he said. “I believed that the U.S. was more organized than El Salvador, like it would never go wrong, like you are never going to make an error and you go to jail when you don’t have to be there. That was my mistake.”

J.Z., who is now 18, recounted his story in his family’s living room, in a humble apartment about an hour east of Brooklyn in Suffolk County, Long Island. He had just walked his little brother home from the school bus stop, and an episode of “SpongeBob Squarepants” blared on the TV.

Short and baby-faced, with a mess of shaggy black hair, J.Z. spoke Spanglish peppered with American slang and talked excitedly about his dream of becoming a chef and opening his own restaurant: “It’s going to be so lit!”

He grew up in a small town on the southern coast of El Salvador, near the border with Honduras. He didn’t know his father, and his mom migrated to the U.S. when he was 1, leaving him in the care of an aunt. His mom supported them with money she earned working as a hotel housekeeper, but in 2014 when his aunt fell ill with complications from diabetes and gangsters in his community began to threaten him, J.Z. felt he had no choice but to trek north alone through Mexico to the Texas border.

“I was thinking, I’m not going to be someone here,” he recalled. “Probably I’m going to die. My aunt is going to die, and who is going to take care of me? I took the decision to come here [to Long Island] to be someone.”

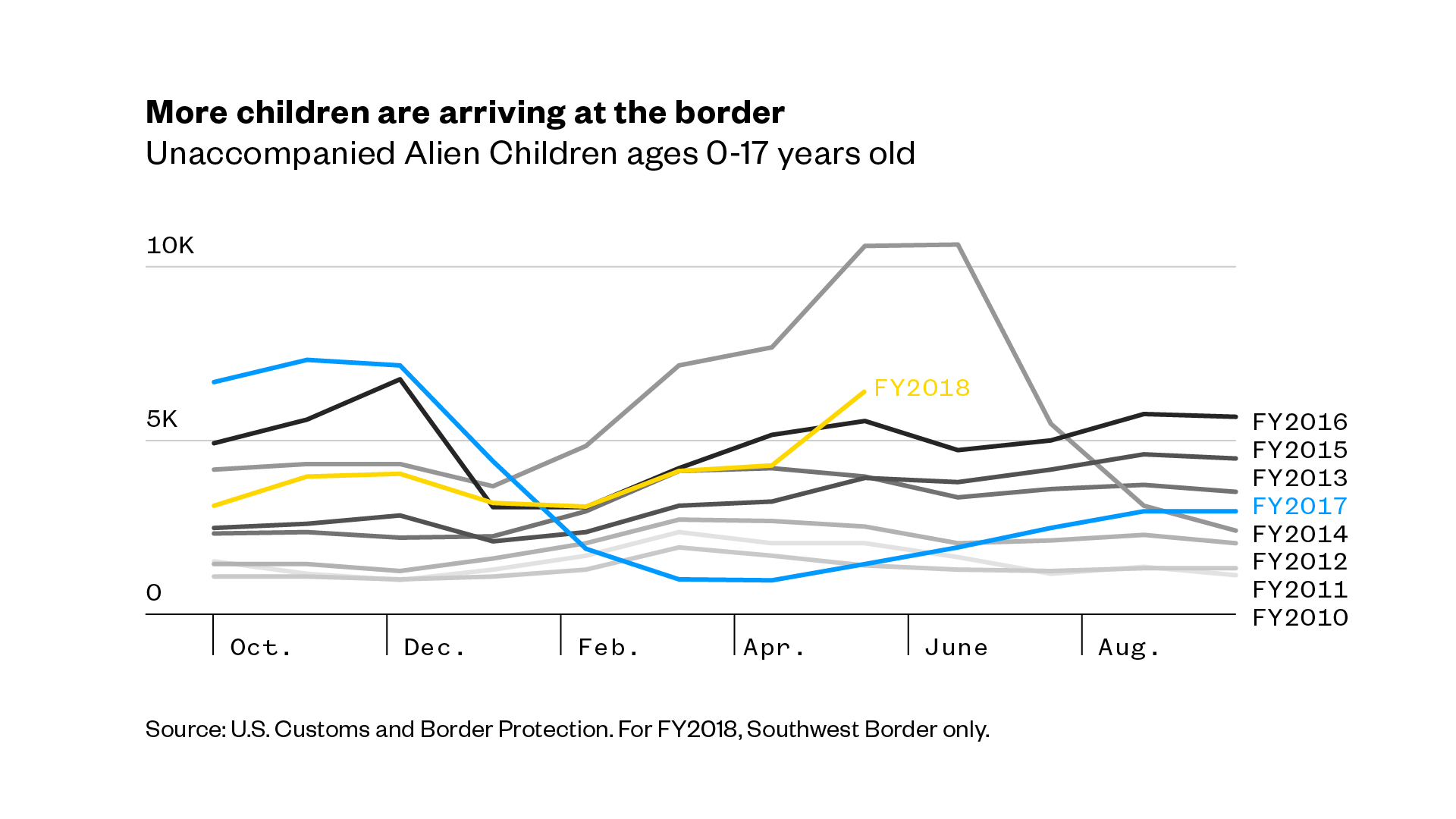

He is one of more than 210,000 so-called Unaccompanied Alien Children, or UACs, from Central America and Mexico who came to the United States from 2013 to 2016, many of them fleeing violence at home.

Responsibility for dealing with the ongoing crisis is split between Homeland Security, which enforces immigration law and oversees border security, and ORR, which is under the umbrella of the Department of Health and Human Services. Most unaccompanied kids aren’t trying to cross the border illegally; they are turning themselves in to Border Patrol agents and seeking asylum. So ORR cares for them and places them with family members or sponsors while their cases work their way through immigration court, a process that can take years.

J.Z.’s path through the immigration system when he first arrived as an unaccompanied minor was typical for how things used to work prior to the Trump era. He turned himself in to Border Patrol and spent three miserable days in a temporary holding cell commonly known as a hielera or icebox because of the frigid temperatures. He was soon transferred by plane to a shelter operated by ORR in the Bronx, where he stayed for 11 days. He wasn’t free to come and go, but he had no complaints about his treatment.

“It was really good,” he said. “If you are hungry, anytime, they can make you food. You can go to school. You have clean clothes. Everything you need, you can have it.”

The agency connected him with his mom, who came to claim him from the Bronx shelter, and he quickly settled into life in this country. He was wowed by his first glimpses of the Manhattan skyline and equally impressed with his family’s living situation compared to how it was in El Salvador.

“We were driving to Long Island, I was just looking at all the buildings,” he said. “Then I took her phone — I’d never seen an iPhone before. I was like, my mom is rich!”

In truth, his mom worked long hours to support him and his younger brother, who his six years his junior, and a younger sister, who was born last year.

And there were more similarities to life in El Salvador in his immigrant enclave on Long Island than he expected. The worst was the realization that he hadn’t entirely escaped from MS-13, which police have linked to several grisly murders in his community and nearby towns. The area’s high schools are considered fertile recruiting grounds for new members.

“I was like, OK, I’m safe — it’s like, no more problems, no more gang stuff,” J.Z. recalled. “Then when I heard about the gangs, I’m like, ‘Yo, gangs don’t exist in the United States.’ I was really thinking like that.”

It’s fair to say J.Z. was not a model student. He struggled with English and took a job in a restaurant, working long hours to help support his mother. School records show that he came late and slept in class. For classes where he could speak Spanish, his mom found teacher comments on his report card like “It’s a pleasure to teach your child.” In other, he got remarks like “Not working to potential.”

He also became a target for bullies, as evidenced by dozens of Facebook messages he received from one boy in his class. The boy and his friends mocked J.Z. for riding a skateboard to school, speaking poor English, and working in a kitchen. In one, he threatened to hit J.Z. with a baseball bat. When they followed him after school one day, a fight ensued. J.Z. says he threw one punch that connected, knocking the other boy down. The school said the fight was proof of gang activity, and he was suspended for the rest of the year.

The incident might have been shrugged off as a minor skirmish between high school boys had it not unfolded in the wake of Trump’s declaration of war against MS-13. The president has repeatedly referred to MS-13 members as “animals,” and claimed that the gang is exploiting the “catch and release” system at the border to sneak into the country.

In reality, the acting head of Customs and Border Protection testified at a Senate committee hearing last June that out of 250,000 unaccompanied minors who came to the U.S. since 2011, only 56 were suspected or confirmed of being affiliated with MS-13. That works out to less than one-tenth of a percent of all such cases.

J.Z. suspects that his high school’s resource officer profiled him as a gang member, which led local police to report him to ICE. Multiple reports have detailed the “school-to-deportation pipeline” that exists on Long Island, where school officials, local cops, and ICE work closely to identify gang suspects. In some cases, wearing the wrong color shirt or merely being seen speaking with a suspected gang member can be considered damning evidence.

One day shortly after his school’s classes had ended for the summer, J.Z. tried to enter the auditorium for a cousin’s graduation ceremony. When a security guard stopped him and said his suspension was still in effect, J.Z. apologized and left. The school still reported the violation to local police, and a week later he was arrested at his home for third-degree trespassing, the lowest level of the offense. His mom was at work when the cops came calling, and he says they searched his room for weapons and other evidence of gang affiliation, only to come up empty-handed. He was held at a jail on Long Island for about a month while the local cops waited for ICE to take him to Shenandoah.

“When I took that plane, I was thinking, ‘I’m not coming again to New York. I’m not coming back,” he said. “I was really sad. It’s like I feel like I spent half of my life in there. Six months. I felt so alone that time. So alone.”

ORR’s history dates back to 1980, when the modern U.S. refugee resettlement program was created. Since its founding, the agency has provided cash, medical care, language classes, job training, and other services to help refugees adjust to life in the United States. It still offers those services, but its responsibilities expanded in 2003 following the creation of the Department of Homeland Security.

As the migrant crisis worsened in the mid-2000s, ORR began building up a network of shelters to house kids who showed up at the border until they could connect with sponsors, usually relatives living in the United States. Since October 2014, ORR has placed nearly 142,000 such kids in communities across the country.

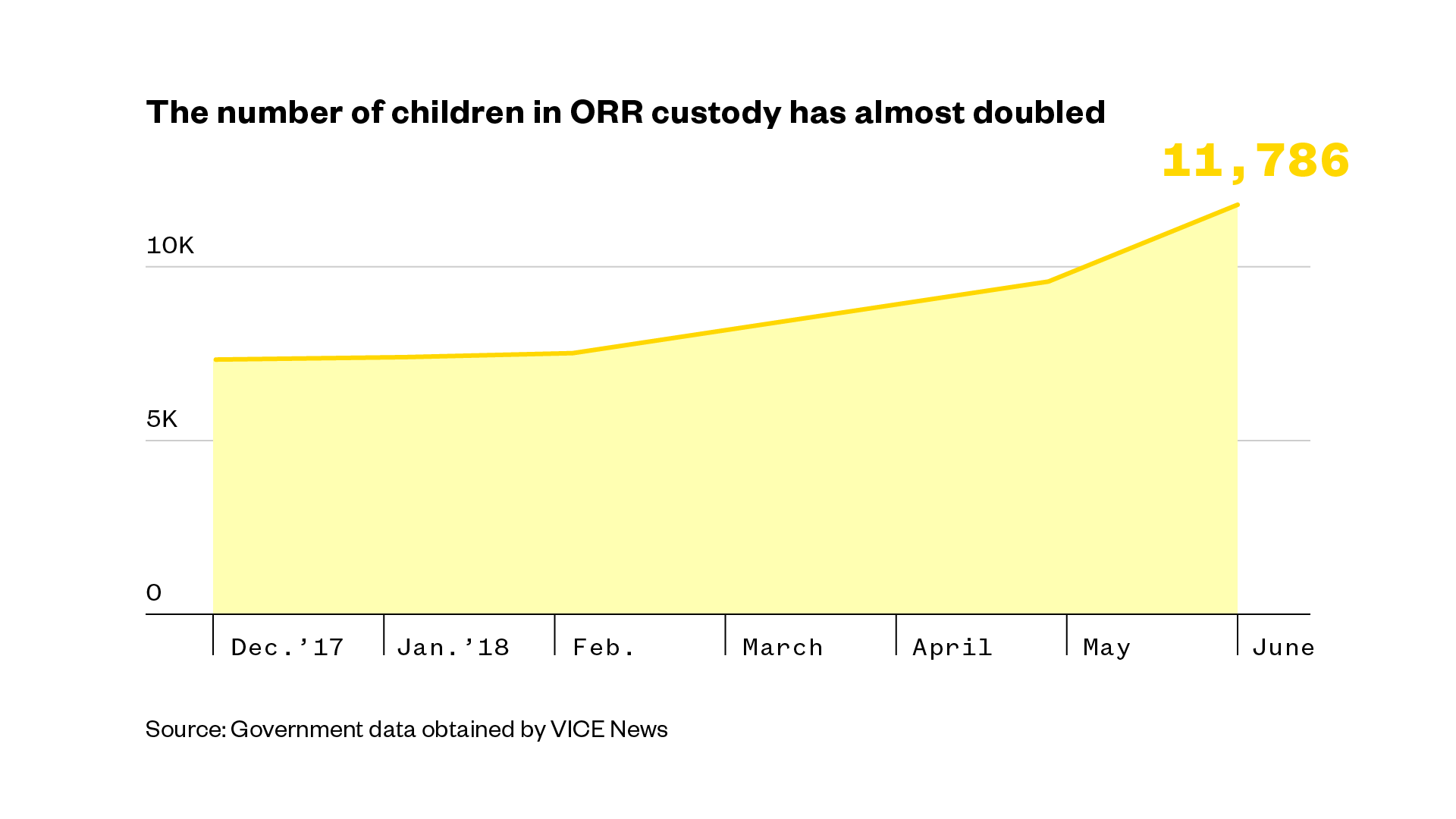

The agency’s detainee population has soared in recent months as a result of increasing border arrivals and Trump’s “zero tolerance” policy to prosecute adults and take away their children. Data obtained by VICE News shows it climbed from around 7,300 last December to 9,500 in May to nearly 11,800 as of June 19.

While new arrivals wait to be placed with a sponsor, they are housed in ORR facilities, nearly all of which are operated by nonprofit organizations funded through grants. The least restrictive settings are more than 100 low-security shelters around the country.

But ORR also operates three kinds of more-restrictive facilities for kids who are perceived to be dangerous, disruptive, or flight risks. Around 130 to 140 children are held in “staff-secure” facilities, and another 30 to 40 kids at any given time are housed in “residential treatment centers,” reserved for youths with mental health or behavioral problems. If children act out in another type of facility or get flagged somehow in the intake process, this is where they end up.

And then there are the actual jails, for kids deemed to pose some type of risk to themselves or others. There are three such facilities — Yolo County, California, and Shenandoah, plus another in northern Virginia — with space for about 70 kids total.

Almost as soon as he arrived at Shenandoah, J.Z. said he was a target for harassment from other kids whom he believes actually did have some experience with MS-13.

“They were doing like gang signs in the bathroom, saying like ‘You have to give me your food, or you have to take something to my room,’” he recalls. “I’m like ‘Yo, I’m not going to do this for you. I don’t care if you’re a gangster. This is jail, bro, where you think you are?’”

He also says facility staff professed to offer counseling but constantly pressured him to confess to being a gang member. It’s reportedly common practice for the government to use information from supposedly confidential therapy sessions to justify detention in stricter levels of ORR custody and in immigration proceedings.

“They were asking me all the time, ‘You’re a gangster. Tell me. This is private. Nobody is going to know. The government is not going to know,’” he recalled. “I never was a gangster or a gang member, so I always say the truth to them.”

Complaints about poor conditions and treatment at ORR facilities have dogged the agency for years. In one lawsuit filed in January, a Mexican youth identified as John Doe said he was hit in the face by Shenandoah staff while he was tied to a chair. According to court documents, he and other kids were punished by being stripped naked and confined to their rooms for more than 24 hours. After Doe attempted hang himself with a curtain, staff allegedly told him, “Kill yourself already.”

Reached by phone, Timothy Smith, the executive director of the detention center, declined to comment about allegations of abuse and referred questions to ORR, which did not respond to a request for comment about J.Z.’s treatment or conditions at Shenandoah. Lawyers for Shenandoah have denied the allegations of physical abuse in court filings.

Doe’s lawyers declined to speak on the record, citing the pending litigation, and they declined to make his client available for an interview, citing fear of retaliation by ORR. Doe has been detained since Aug. 3, 2015, and remains in ORR custody.

Several other attorneys who represent unaccompanied minors expressed similar concerns about speaking out. Because nearly all kids held by ORR are in civil immigration proceedings, they are not guaranteed lawyers like defendants in criminal cases, but the agency provides funding to groups that offer legal aid. Attorneys from these organizations were afraid that ORR would either withdraw the funding or single out their clients for punishment.

At first, J.Z.’s family and friends weren’t even sure where he was. When they found out he was in Shenandoah — a seven-hour drive from Long Island, they couldn’t believe it. His mother, who was pregnant with J.Z.’s younger sister at the time, was distraught.

“It was so frightening,” said Julia Saltman, his former restaurant boss. Saltman helped another local kid who was detained by ICE on gang allegations and became a close friend of J.Z. and his family, supporting them throughout their legal struggle. “It was basically like they disappeared him,” she said. “We were finding out that kids would go down there and go into max security for no reason.”

Carey, the former ORR director, said he could not recall a single case like J.Z.’s, where a kid was taken back into ORR custody after they had already been released to a family member or sponsor. Carey said it’s unclear whether that’s appropriate or even legal. “If they commit a crime in community, it would be an issue for local law enforcement,” he said.

Amid reports of similar cases, the ACLU filed a separate class-action lawsuit last August that challenged the detentions of about two dozen kids who were picked up in gang sweeps and placed in ORR custody. J.Z. finally won a hearing in November where the government was forced to show what evidence they had to prove his alleged gang affiliation.

At the immigration court in lower Manhattan, parents and relatives sat nervously in the lobby as lawyers whispered and scrambled to review documents that had received only hours before from ORR and Homeland Security. J.Z. sat facing the judge with his hands folded, next to his attorney and an interpreter who translated his statements to the court. He wore a black shirt and his already-shaggy hair had grown even longer, so that it was starting to creep down the back of his neck.

An attorney for the Department of Homeland Security told the court that J.Z. had been “identified by a specific source and an unknown source as being an MS-13 gang member,” and claimed his fight at school and the subsequent trespassing incident showed he had “a propensity for danger and violence.” J.Z. explained to the judge that he’d been targeted by bullies, who had followed him one day after school.

“We fought, and by bad luck I won,” he said. “I didn’t think it would be so bad.”

The government claimed that J.Z. had lied about attending a graduation ceremony, but the judge noted that his testimony was corroborated by a school security guard’s statement. At the end of the hearing, the judge said curtly that the government had failed to “meet its burden” to prove that J.Z. was un peligro para la comunidad. He was free to go.

After the hearing, J.Z. wiped tears from his eyes and hugged his mom and younger siblings. He thanked God and said he hoped other kids stuck in ORR detention would have the same good fortune.

“It’s an injustice,” he said. “They locked up everyone for no cause.”

While J.Z. is now free and reunited with his family, hundreds of kids remain in ORR-detention limbo. These include the approximately 2,000 kids who were separated from their parents with no plan to reunite them later and dozens who have been languishing in detention for months with no clear path for release.

As unaccompanied kids continue to arrive at the border, advocates said they are worried the number of kids stuck in ORR detention for weeks or months will increase. Trump’s “zero tolerance” crackdown has spooked potential sponsors out of coming forward, since undocumented families are wary of any sort of contact with the federal government for fear of deportation. Recently, ORR signed a memorandum of understanding with ICE to provide the names, fingerprints, and phone numbers of people who claim unaccompanied children and other members of their households.

And there’s evidence that it’s getting harder for kids in ORR’s secure facilities to get out. A new policy says ORR Director Scott Lloyd must personally approve every release or transfer from these facilities, a situation that children’s advocates say leads to longer detentions. The ACLU of New York has filed a separate lawsuit challenging this policy, which it says has has affected 747 children.

“ORR is inventing excuses to step up or put kids in increasingly more restrictive environments as a way to detain them indefinitely,” said Poonam Juneja, an attorney involved in the Flores case. “They’ve been inventing excuses not to release kids to a willing and able relative.”

ORR spokespeople referred questions about decisions regarding placement of kids in secure facilities to a section on the agency’s website, which says it’s only an option in cases where the child “poses a danger to self or others” and “has been charged with having committed a criminal offense.”

J.Z. returned to school after he was released last November, but his future remains uncertain and he could still face deportation. He has a date in immigration court this week that will determine what happens next.

In the meantime, J.Z. is trying to keep a low profile, attending summer school for math, spending time with his family, and taking cooking lessons from his old restaurant boss, Saltman, who thinks he’s on his way to becoming a gifted chef.

“He’s got a whole community behind him that’s totally invested in his future,” Saltman said. “We know where he’s going. He’s got like tons of opportunities. He’s so easy to back. He’s been so easy to back since Day One.”

J.Z. tries to keep his hopes up, but the recent wave of media coverage has hit close to home for him. The recent audio recording of young boys and girls wailing in terror and calling for their mothers and fathers was especially painful for him to hear.

“I know how they feel,” he said. “It’s not easy for them. They don’t know what’s happening, they don’t know what going on, if they’re going to go to their parents or not. You’re feeling afraid all the time.”

He’s also certain the flow of migrants from his native El Salvador will continue as long as people are being forced to return to places where they face extortion and death.

“It’s never going to stop,” he said. “Donald Trump, he doesn’t know anything. He’s going to keep deporting people, but more people are going to come.”

Keegan Hamilton covers immigration and criminal justice for VICE News.

Carter Sherman contributed reporting.

More

From VICE

-

(Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images) -

(Photo by Stuart Westmorland / Getty Images) -

-

Peerapon Boonyakiat/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images