If you ask someone with no interest in combat sports to name two boxers, there’s a good chance that they will name Muhammad Ali and Mike Tyson. They are the two great heavyweights who are so easy to recall and they are often painted as polar opposites.

At the height of his popularity Ali was probably the most recognizable person on the planet. You could take his photograph to parts of Africa and children there would know him before they recognized the president of the United States of America. His exile from boxing through three years of his physical prime for his refusal to be drafted to the US military, and his support of the Nation of Islam made Ali one of the most divisive figures of his generation and served to see him transcend his sport in a way that no other athlete has to this day. Many remember him for his comeback and his out-thinking of the seemingly unbeatable George Foreman, though he is just as easily remembered for not knowing when to call it quits and his brutal shellacking at the hands of Larry Holmes.

Videos by VICE

Mike Tyson is remembered primarily as a villain. Or rather as a lost cause and wasted potential. The greatest fighter who ever lived, mislead after the loss of his father figure. Under the charge of Cus D’amato and Kevin Rooney, Tyson won the world heavyweight title at the age of 20 by knocking out almost everyone in his path. Then it all fell apart. Convicted of rape, Tyson was sent to prison and remained out of the ring from June of 1991 until August of 1995. When he returned he wasn’t the Tyson of old, he was just a flat footed brawler. The fights became grinding slogs and when he met the best of the best in Evander Holyfield and Lennox Lewis, he was convincingly bested.

There’s more to both men’s stories. It would be easy to turn Ali heel by recounting his misuse of his stature in the black community to turn it against Joe Frazier. It would be equally easy to show Tyson in a positive light. But simplifying a man into print will compress him into a one-dimensional cliché. What was captivating about each was their approach to the game of fisticuffs—each so unique that it could draw in the most casual of observers. Let us examine these styles and play with that most important of hypothetical match ups—Muhammad Ali versus Mike Tyson.

Living and Dying By the Jab

Classical boxing is lead by the jab. In fact the terms ‘jab’ and ‘lead’ are often used interchangeably. As a 5’10” heavyweight, Tyson was always going to be at a disadvantage in a straight up jab-off. Working with Cus D’amato, who trained fighters in “elusive aggression”, Tyson was built around drawing the jab and getting past it. The jab that is expected and prepared for is easily countered—and through aggression, paired with constant, disciplined head movement, Tyson was able to draw panicked jabs and counter them.

Due to his extensive use of hooks and uppercuts rather than the traditional straight blows, Tyson is often remembered as an infighter. The truth is that Tyson’s best punches connected on the way in. He wasn’t the kind to press into his opponent’s chest and chop away with grinding, short blows to the body. The opponent jabbed, it flew over one of Tyson’s shoulders, and he immediately retaliated. It could be a left hook, it could be a right across the top of the jab, it was the timing and the movement of Tyson that made it more than the power of the blow.

The more Tyson’s opponents became concerned about not letting him close, the more they’d pump the jab. And the more often they pumped the jab, in hopes of a solid connection to keep him away, the more openings they exposed for Tyson to score through.

But the fact that Tyson was Tyson didn’t undermine the principles of boxing. He was still a short heavyweight, and the jab was still a problem. He was just exceptionally well trained and disciplined in getting around it and using his opponent’s jabs to his advantage. In the worst performances of his career, when Tyson tired and couldn’t maintain the constant head movement through the rounds, Tyson found himself on the end of the jab and unable to get inside.

Tyson lived and died by his opponent’s jab, and his ability to manipulate and draw it through intimidation and crowding.

Cassius Clay to Muhammad Ali

Young Cassius Clay meanwhile, as a 6’3″ heavyweight, with a seventy-eight inch reach (seven inches on Tyson’s) recognized the jab as his key weapon from day one. He didn’t throw out the piston-like jab that had been the fashion though. He wasn’t Liston or Foreman, driving a railway spike through his opponent’s head. No, Muhammad Ali’s jab was more sinister: flicked out with his hand loose inside his glove. He targeted the eyes like no-one else in the game and made a habit of cutting his opponents in his early career. Poor Henry Cooper’s face seemed to be coming apart at the seams when Clay was done with him.

Ali’s best power punch was always the right hand counter as his opponent retracted their jab. He called it the Anchor Punch when it became the focal point of his controversial second fight with Liston (which Liston likely threw), but it had been winning Ali fights for years. He laid out Zara Foley with the same blow, and Ali’s sparring partner Jimmy Ellis made his mark timing the same counter through the heavyweight tournament to decide a champion during Ali’s exile from boxing.

When Ali returned from his three years away from the ring, he looked shoddy. He couldn’t coast on his speed against the grinding journeymen, and against the best fighters with the best coaches, he found his flaws being exposed to the world. The change in Ali was noticeable. He went to the clinch more and he would conserve his strength. There would be brief periods of activity from Ali, and then periods where he would deny his opponent activity through the clinch.

Where there was a point where one could clearly say “that’s complete Tyson”, there is no such point for Ali. When his speed and footwork were there, his ability to tie opponents up and wrestle with them were not. Ali’s shortcomings on his return forced him to grow and adapt in order to stay relevant, and in that we saw him become a more complete scientific boxer. Had he come back to the ring with the speed and dazzle of his youth, or had success with the same he had used back then, we might not have seen him grow to out-think George Foreman or take many of the biggest victories of his career.

The Dip and the Bob

One of Ali’s greatest bad habits was punching down on his man. His success in spite of this caused the habit to become even more ingrained. Go back to Ali’s bout with the Old Mongoose, Archie Moore (who had trained Ali for a while before a falling out over doing chores at camp). Moore was well past his best and relied on his unorthodox cross guard and the habit of heavyweights and light heavyweights to get tired after a few rounds of good punching at him. They’d stand still in front of him after hitting his guard and eventually he’d crack them with a good counter. Archie could hit too, he holds the most professional knockouts of anyone in ring history and in fact lectured a young Cassius Clay of the importance of developing punch for when his feet eventually slowed down, but Clay didn’t want to hear it.

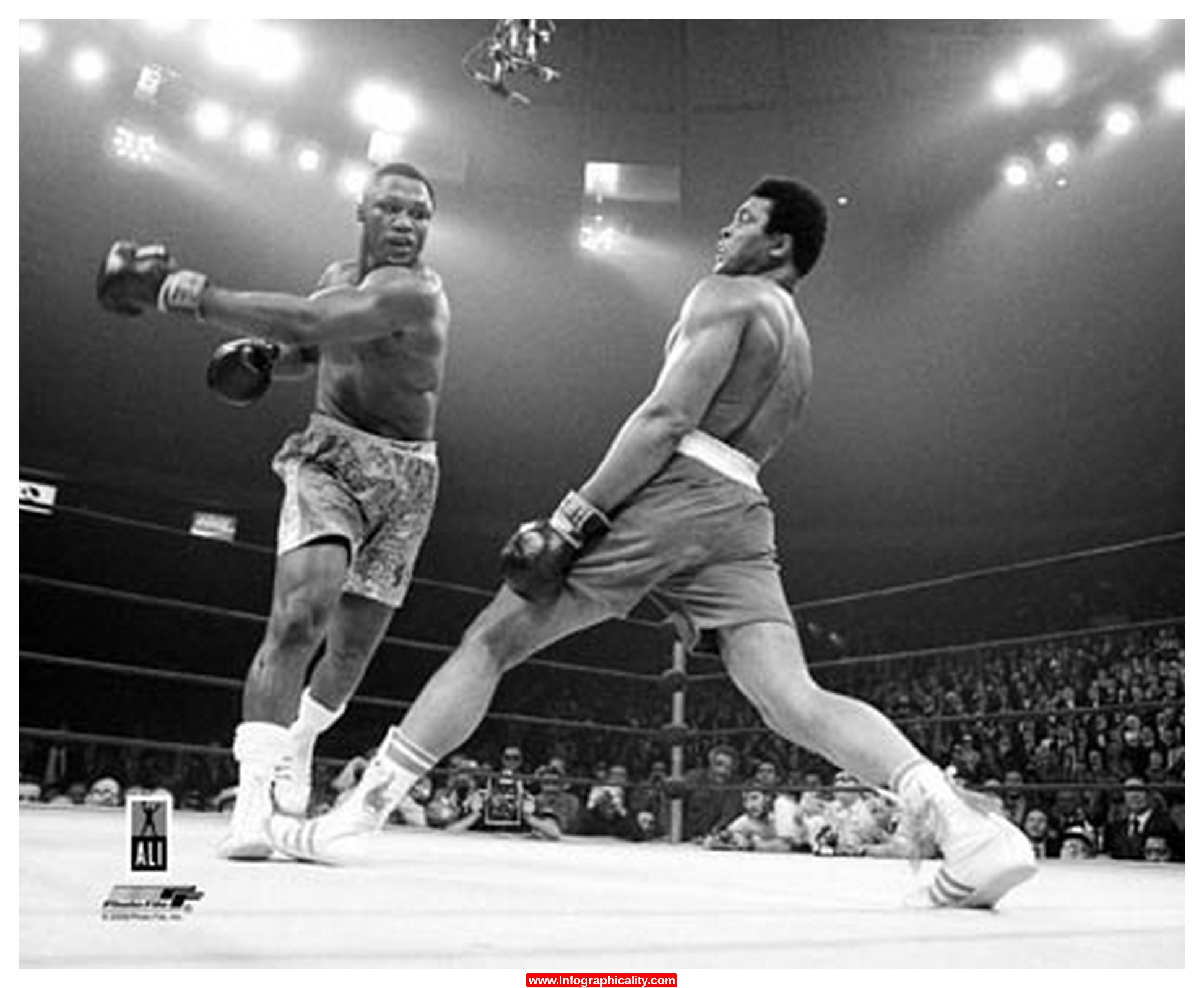

Ali punched down on Moore, and on Joe Frazier in their three fights, relying on his length and speed to pull him out of the way when they returned. The danger of punching down at an opponent is, of course, that you are standing close enough to hit, with your hands down by your waist. Against Frazier, this resulted in plenty of moments like this:

Here an already aged Cus D’amato demonstrates the same principle in discussing a prospective match up with Joe Frazier with a young Ali. Ali’s dropping his hands for the uppercut cost him in the bout with Frazier exactly as D’amato predicted it would:

The reason Ali could do this was partly his reach advantage, but partly because both Frazier and Moore bent over at the waist to avoid punches. This worked well for them the majority of the time, but it also meant that they had to come out of the stoop to counter. You can’t advance across the ring with any rapidity while doubled over. What you will notice over and over in the Frazier is constantly advancing, except when he is bending to avoid punches.

When Ali hit the ropes, or slowed down, that was when Frazier cracked him with the left hook in answer to Ali punching down on him while he bobbed. Frazier was at a mechanical disadvantage in his dip, at a tremendous reach disadvantage, and he was still able to get in good blows on Ali when the latter committed the sin of punching down on him. One of the really interesting points of the Tyson – Ali match up is that Tyson’s vertical movement was not like Frazier’s at all.

Tyson would bend forwards at the waist when appropriate, but he would more often utilize a bending at the waist to the side, or rather a deep slip. With these deep slips he could get to the side of straight punches and underneath hooks. They aren’t a particularly natural maneuver and the stories go that Tyson used to practice them up and down the gym while holding a barbell plate.

Much more of Tyson’s movement was performed by bending at the legs and this is highlighted in this nice clip of him showboating:

Where Joe Frazier would bend straight forwards almost every time with his forearms in front of his face, and this made him very susceptible to the best uppercutters, Tyson kept his eyes up, his back straight, and had control over his body even while deep in a crouch or dip.

The main point was that Tyson was more varied in his evasions than Frazier, but more important he could advance upon his target much faster while he was evading punches—where Frazier had to come almost to a dead halt while he bent over at the waist to avoid the blows.

Of course, Ali had beaten Floyd Patterson, something of a prototypical Tyson, but Patterson had been past his best days and was never as active in his head movement as Tyson. In fact, in their second bout Patterson was troubled by back spasms, which raises interesting questions about the longevity of the D’amato style.

On the Inside

While Tyson was not the infighter that Frazier was, he appreciated the value of aim over power. When Muhammad Ali tired George Foreman out along the ropes in Zaire, he genuinely seemed to think he had found a new way to fight all of his bouts. When he went to the ropes shortly afterwards in his third match with Joe Frazier, he took a fearful beating.

Where Foreman swung wild against Ali’s forearms and lost his temper, Frazier drove his head into Ali’s chest, where Ali couldn’t hit it, and started digging shorter punches inside of the elbow. When the elbow came in, he’d go around behind it. When the head came down, he’d uppercut. When he got the chance to step to an angle and throw the left hook through the center of Ali’s guard like it was a straight punch, he’d take it. And if Ali punched back he’d hook. That’s the difference between punching along the ropes and good infighting—good infighting aims to force the opponent to make adjustments, and then accommodates for those adjustments. It’s tiring to keep up with good infighting, swinging along the ropes only tires the man that’s doing the swinging.

Tyson’s best close range set up was that right handed lever punch. The double up of right hook to the ribs or kidney, followed by the same hand coming immediately up the middle in an uppercut. This scored Tyson a great many knockdowns and even if it failed, it served to keep the opponent upright so that the body shots would continue connecting on a nicely stretched out abdomen.

Tyson’s best method along the ropes was angling off to his left side, into a southpaw stance. Through his best days, this almost always spelled trouble for his opponents as the angle of his right hand changed and it was able to hook or uppercut right up the middle through their guard. Out in the center, along the ropes, anywhere he could hit this slight shift, he would.

But the x-factor through the whole Ali—Tyson match up is the clinch. Ali, like Jack Johnson, used the clinch to separate the men from the boys. Ali loved to cup the back of the head with one hand to bend the opponent forwards, and then use his other hand to cup their arm at the biceps. If he kept the elbow of the hand on the opponent’s neck close, he could effectively muffle or stop all of their blows, but keep the tie up lose enough that most referees would encourage the clinched man to keep working. It was Ali’s greatest trick and he knew it.

Norman Mailer recounted in The Fight going to see Ali in training ahead of the bout in Zaire, and how most of Ali’s sparring sessions in those days were simply him taking young, promising heavyweights like Larry Holmes to the ropes and tying them up. Being Mailer it’s filled with metaphor and Ali somehow becomes a butcher selecting punches like cuts of meat, but it’s a fascinating insight nonetheless.

Ali ruined Joe Frazier in their second fight as Frazier couldn’t get anything off inside this clinch. When a referee was chosen in the third fight to specifically prohibit this, the bout was a grueling back and forth war. And why is all of this interesting? Because an aged Larry Holmes only lasted four rounds with Tyson, but each time he tied Tyson up in this manner, the young banger looked completely ineffectual. Tyson was notably upset by this and even complained to Kevin Rooney between rounds that Holmes was holding him.

The fun thing about a hypothetical fight is that you can never be proved wrong in your pick, but you can remain absolutely adamant that anyone who picks the other guy is a mug. The standard is “prime Ali versus prime Tyson” and I think that is a bout which Tyson could take. “Prime” meaning athletic prime, that is. Young, fast handed, fast footed Ali, dancing and jabbing erratically and hoping he never gets punished for it.

The fight I’d much rather see is Ali of the second and third Frazier fights. The one who would hold for a round, jab for a round. The one who would drag Tyson into the later rounds where he always had trouble with his breathing and with maintaining his head movement. Even with those two fighters, the camps they went through and the strategies they came in with would change the course of the bout. But that is what keeps the match up so important to the boxing fan—the fact that no matter what someone says Ali or Tyson would do, someone else can give you an example of when they did the exact opposite.

Of course, the real interesting question is how they would cope with Joe Louis…

Pick up Jack’s new kindle book, Finding the Art, or find him at his blog, Fights Gone By.