Gregg Wallace is at the bar with all his mates. Shots, pint, shots, pint, brandy, brandy, shots. Someone says “Millwall” and everyone shouts, “MILL—WALL!” Someone drops a load of pint glasses and everyone shouts “wahey”. What I am saying is: it is A Big Night. Gregg Wallace is feeling good: head freshly shaved, smooth and soft; Gregg Wallace has slapped his dewy cheeks with a heady aftershave; zip-down polo freshly ironed, suede loafers newly brushed. Smell good, feel good, look good.

Gregg Wallace goes round each of his geezer mates in turn with a single pointed finger: Drink? Drink? Drink? And then the world stops— he sees her, across the room, back turned to him, surrounded by three or four of her friends. They are laughing, so light and airy, that magical way women do: all of them in heels and tight dresses in all the right places, and their hair huge and primped, glamorous eye shadows and perfect strong lip lines, all of them gorgeous, all of them, but her: her, she was something else, firm and curvaceous and caramel-dark, time slowed around her, every head in the room turned to her. (The joke here that we’re getting to is this: Gregg Wallace fucks puddings. The woman you think is a woman is actually just an enormous sticky toffee pudding in a bandeau dress. He is going to fuck this pudding.)

Videos by VICE

“Cor,” Gregg Wallace says, peeling a single flat palm down his suddenly sweating face. “I think I’m in love.”

* * *

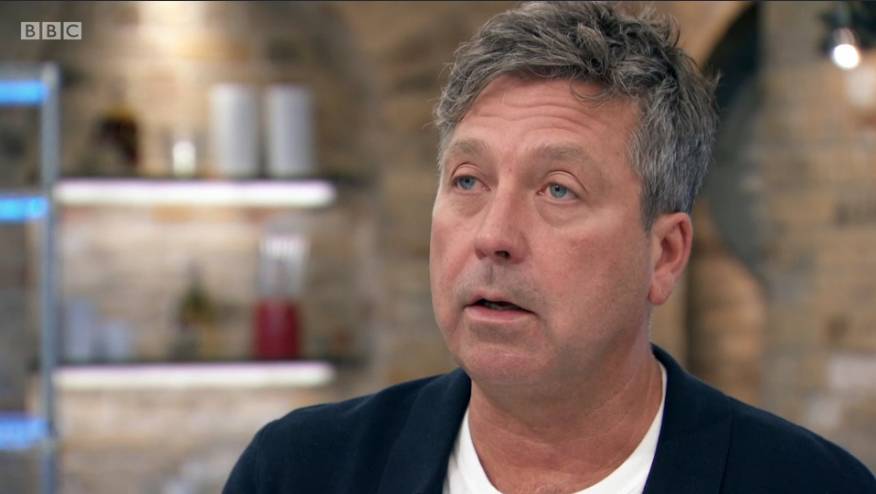

MasterChef is a TV show where home cooks compete for weeks in pursuit of a swirling M-shaped trophy and a shot at a cookbook deal. John Torode and Gregg Wallace host. This is a peculiar dynamic because neither of them seem to especially like each other: as they stand and shout easily-edited bon mots about food they’ve just eaten, six feet away in a coldly-lit studio, their dynamic is more like two ageing advertising executives who know each other’s names but are tired of seeing each other at the same party, or two university art teachers grading coursework ahead of the Easter break. Two father-in-laws, briefly forced to make friends as their sons marry each other. John Torode is tired of being alive, and tired of eating food, and too tired to do anything much more than wear zip-thru over-shirts and say “this better be good”; and Gregg Wallace, the polar opposite of this spectrum, is TV’s greatest living madman, who wishes to die by putting his head in a bucket of cream cheese. Both men want to die, is what I’m saying. It’s just how they want to go that colours their opinion of food.

The format is this: the first rounds, held over a three-day week, see seven cooks compete for a place in the Friday quarter-final, with the winners of that going through to the next rounds. This is the fun part of MasterChef, and it is deeply un-fun. Three cooks are lost from the first heat – the “Market Round”, where they go into a faux shop and panic grab a series of seasonal items and store cupboard essentials – lentils, rice, vegetables; poussin, parma ham, mince; somebody always, derangedly, does something with prawns – with the instruction “cook something that tastes good”.

Very often, competitors fail at this low hurdle: they will lurch between two extremes – “doing something both technically and flavour-combinationally insane, and failing at both, like deep-frying an orange and serving it with beef”, or, “playing it too safe and failing to alight the palate or the crotch; someone always makes pasta with meatballs for some reason”. Three competitors are shorn from the process after making exactly one meal, and they retreat to a small alcove-like room, panting, exhausted, to cry. “These home chefs love to cook,” the breathy voiceover tells us, as we watch people psychically disintegrate after fucking up a rack of lamb. And I think: do they? Do they?

Why do we watch cooking shows? There are two kinds of cooking shows: warm, cosy, hug-like ones, where a soft-spoken wonder chef in a sparkling and immaculate kitchen makes three dishes over the course of a half-hour, speaking to you directly, intimately, like a friend might, smacking their lips and making semi-orgasmic sounds, making you – yes, you! – believe that you have the tact and flame control to seal a chicken breast with that hard, almost-caramelised outer skin like they do (you do not). The second is something more high-pressure and manic, akin to the genius-cum-chaos we are told abounds in every professional kitchen on earth: shouting, wailing, pressure, noise, cauldrons of hot water boiling over, Gordon Ramsay, resplendent in white, just yelling.

MasterChef is this one. When people fail to set a fondant they throw a tea towel at their forehead and exhale all the air in their body. When Gregg Wallace tastes a ravioli dish that falls slightly short of the promised punch of flavour it was supposed to deliver (someone has spent more than an hour of their life making these three pieces of ravioli) he delivers the news with the face and tone of a doctor telling you your dad has died. “It’s good,” he says, about pasta that undoubtedly tastes better than everything I have ever cooked in my life put together, Gregg Wallace tiptoeing up to you like he has to tell you he just strangled your dog. “It’s just: Not. Showing me. What you can really. Do.” Go to the small brick room and cry about it, amateur. You’re going home.

Cooking shows are here to make you hungry, but they are also here to make you stressed. MasterChef mainly does this by throwing the same seven or eight chefs into the same challenges and watching them collapse under the same challenges, again and again and again. You’ve got:

– Woman with a fine mastery of her cultural food background (curry, perhaps, or Asian flavours), which is all well and good early rounds, but then is consistently marked against her when she cooks literally anything that doesn’t have a bell pepper in it;

– Large thin pale boy who is almost certainly wearing a fitness tracker and today has decided to Play It Safe;

– Real Big Lad who seems to physically be falling apart at the very seams and always seems to forget something very crucial about the dish he is preparing, e.g. he is making chips, and had cut and seasoned the chips, but now he’s got the one-minute warning and has realised, with a jolt of panic, that he has somehow forgotten to fry the chips;

– Nan-aged mum who has replaced her kids w/ Moroccan cooking;

– PhD student who is really horny for gadgets and constantly seems to be sprinting towards a fridge;

– Mum-of-three who absolutely cannot plate for shit and was just happy to be here;

– Bloke in interesting glasses who ALWAYS does some weird shit (“A fennel and pomegranate pancake!”);

– Uptight former police officer who absolutely NEVER does any weird shit (“A very ordinary three-egg pancake!”)

– Small neat girl with high pony and eyeliner who quietly impresses Gregg and John with a new twist on an old classic;

– Entirely sexless 40-year-old bloke who fuses nine or ten cuisines at once, Always Does A Puree;

The ultimate winner is normally “quiet short woman who shows iron-core of determination” or “bloke w/ beard who rolls his sleeves up”. “Wonky 24-year-old who’s best mates with his dad” might take it this year, but you never really know until the end.

A BRIEF CONTENT SIDEBAR THAT IS POSSIBLY ONLY TRULY RELEVANT TO ME AND ME ALONE, BASED ON THE BIZARRE NICHE CONSUMPTION OF TELEVISION I HAVE, AND MAYBE IT MAKES SENSE TO OTHER PEOPLE BUT NOT A LOT OF THEM; WHAT I AM ABOUT TO SAY IS EITHER THE MOST ACCURATE THING YOU (YOU.) HAVE EVER READ, OR IS ENTIRELY POINTLESS AND WILL LEAVE YOU UTTERLY COLD, THERE IS A WILD BINARY HERE, IT CAN ONLY BE ONE OF THE TWO: HOWEVER I’VE THOUGHT IT NOW SO I HAVE TO GET IT OUT OF ME—

Spiritually, Gregg Wallace from MasterChef and James “Arg” Argent from The Only Way is Essex are the same person. They are the same. The same person. Gregg Wallace is just an older version of James Argent. I don’t want to elaborate on this because I don’t need to. It is objectively correct. Gregg Wallace is James Argent. Same person. Thanks for listening.

* * *

We’re back to Gregg Wallace now. Gregg Wallace, eyes open, lungs panting, deep in the blue-black darkness of his bedroom. Toffee sauce all on his hands, his legs, his chest. Especially around the cleft of his chin. It’s been a few weeks since they met. Their hands find each other in the dark (the monster has hands). When new relationships start, everything you say in these blissful post-coital minutes feels as significant as the entire universe around it. Like everything might be etched in stone one day. Recounted to the grandchildren. Like every moment you’re living through is something eternal for the two of you to share. The start of something with a capital-S. She’s got her legs together (the monster has legs) and is clutched against him on her side, quiet, snug, still but still awake. He takes his toffee-stained glasses off and puts them on the nightstand. Kisses her sticky forehead. “Pud,” he says (Gregg Wallace affectionately refers to the monster as “Pud”). “Pud, I…— I love you, Pud.”

* * *

Round Two and things start to escalate, and soft spots are formed for series favourites (I am currently rooting for a cheery Welsh mum with a Foo Fighters tattoo and a crush on Gregg Wallace who always does exactly enough to get through each round, proving once again that most competition shows can be won simply by neither fucking up or excelling, for 12 weeks, until a war of attrition leaves you as the only competitor standing: it’s fun to watch her beat down gadget nerds who always serve up a puree and some sort of flavour dust by just doing a nice trifle or some pasta or something). At this point, though, the stress starts to escalate.

It’s hard to capture exactly the chaos of MasterChef: in the quarter-finals, chefs are tasked with cooking exactly one dish, to a broad brief, and every time they tell John and Gregg what they are going to cook J&G retreat to a small room and shout about how shit it sounds and how they don’t have the technical ability to pull it off. Slowly, incrementally, MasterChef invests you into its central stress – fundamentally, this is a show where the worst thing that can happen is a sauce splits, or some meat is a bit underdone, but in the MC kitchen these disasters are akin to death – tugging you into its conceit, until, oh: you find yourself, hands clasped against your chest, gasping as a Scottish PE teacher fucks up a langoustine.

* * *

MasterChef, in its current form – i.e. a sort of multi-sensory assault, and not Lloyd Grossman quietly tapping around a black-floored empty studio politely asking middle class people what pesto they’re making – has been around since 2005, which means you have, at some point, found yourself sprawled on a sofa-chair watching it once with your dinner. And that means, too, that you have at some point wondered how you would do on the show: I had a flatmate once, who, convinced, told me he would win the first heats with his spaghetti bolognese, which I had tried and was mediocre at best. How many things, really, can you cook? I wonder what I’d do if I came to – sweating, as if from a nightmare – strapped in an apron in the MasterChef kitchen. “Gregg, John, I’ve cooked for you: mildly salted chicken”? “John, Gregg: today I’ve prepared for you avocado mashed on a bagel, w/ some halloumi I lost track of a bit and let go over, no sauce”? “John-John, Greggo: I’ve mixed granola with yoghurt, which I have for dinner maybe three nights a week because I properly can’t be arsed. I’ve spiced it up with the addition of: honey”?

And so it’s weird, then, when watching MasterChef, finding myself calling people idiots for simple mistakes like not resting meat long enough (I have never rested meat in my life) or leaving a smudge of sauce on an immaculate white plate (I still cannot consistently poach an egg). This is how it hooks you in: those first few rounds, watching people mentally implode while trying to bring fruit flavours to a meat dish; the quiet satisfaction of watching someone plate up a gourmet meal and getting a tight nod from John and Gregg; those endless, endless final rounds, all the energy and joy of cooking finally sucked out of it, as competitors cook for army squadrons, and restaurateurs, and a vast array of food reviewers who wear blazers with jeans. MasterChef starts quite joyless and somehow gets more chaotic and depressing, and somewhere in that backwards alchemy from gold to shit it makes you fully invested: and then, come final day, when (hopefully) Foo Fighters mum beats all comers with some turkey dinosaurs and a fun new take on beans on toast, you weep, emotionally exhausted, weep into the same stir-fry you’ve been making two nights a week for five years now. MasterChef takes someone silently making a sauce and turns it into high drama. How is that possible?

And the sea washes up against the shore. Gregg Wallace, toes soft and naked in the clean muscovado sand, white linen pants, white linen shirt, wind fluttering the flower arch above him. She’s late, but not too late, the sun dizzily setting out there beyond the sea. Organs play. A few close friends rise to their feet. He turns and sees her, a vision in white: she looks— God. She looks like the most beautiful girl in the world. Touch the veil, kiss the bride. Lift her by the legs and hoist her to your cheek. Finally, he thinks, finally, I feel peace. He has married the woman of his dreams. Carry her towards the sun.

“I love you!” he shouts, spinning her in his arms. “I love you, Pud!” And then he drops her joyfully in the sea. He watches her sticky toffee head bloat and soak apart. He watches caramel sauce leak out of her like an artery burst. “N—no!” Gregg Wallace screams. “N—no! NO!”

“NO!”

“NOOOOOOOO!”