This article originally appeared on Noisey UK

It’s a bit weird interviewing Paul McCartney. A day and time is agreed, your phone number is taken, and in the following weeks you tell your mates about it, you tweet about it, you tell pub smoking areas about it, you tell your mum about it. Everybody knows Paul McCartney. Everybody loves Paul McCartney.

Videos by VICE

But it’s not until an unknown number calls you two weeks later, you answer it, and the voice at the other end says, “Hey Joe, it’s Paul here,” that you fully comprehend what is happening—“Shitting hell, I’m on the phone to Paul McCartney.” You’re talking to a living Beatle, a 21-time Grammy winner, a figure more integral to the history of contemporary music than the humble turntable – he’s waiting for you to say something, and all your questions just abandoned your head and floated skywards like dead souls.

If articulating those questions was hard, writing them was ten times worse. In the build up to the call, I toyed with all sorts of research. Four CDs of Pure McCartney arrived first, his new 67 track brain-busting compilation of the greatest tracks he’s ever blessed—a blueprint, basically, for modern pop music. Then a book arrived in the post titled Paul McCartney: The Biography, written by Philip Norman. Totalling an intimidating 853 pages, it occupied a space on the left of my desk for days; casting a dark, towering shadow on everything within a five metre radius, and taunting me silently like a gremlin. Next, an incredibly in-depth BBC radio interview went online, in which Paul was thoroughly dissected for an hour about his entire career. Finally, as if to twist the knife, he dropped a six part virtual reality documentary containing stories, reflections and anecdotes that span his whole musical output. And this is just 2016, I’m tediously listing off. I’m not including every little bit of McCartneyography that has been happening since “Love Me Do” dropped in 1962.

What purpose can another interview with Paul McCartney serve anymore? What could I ask that hasn’t been asked a million times? How did you write this thing? Nope. How did you meet John? Nope. What do you think of modern pop music? Nope. Something something something Kanye West? Nope. Nope. Nope. As Adam Gopnik wrote about McCartney in April’s New Yorker, “What’s to know is known.” So, what then? Should Britain stay in the EU, Paul? What do you order at Dominos? Do you ever covertly look at people in the reflection of train windows? Are ghosts real?

After two weeks of blank stares, my extremely thorough research reached its conclusion—there was nothing in particular left to question Paul McCartney about. So, I figured, my only hope of an angle was to talk to him about exactly that: nothing in particular. Whether or not a conversation with Paul McCartney about nothing in particular can be interesting or even remotely publishable, I was about to find out.

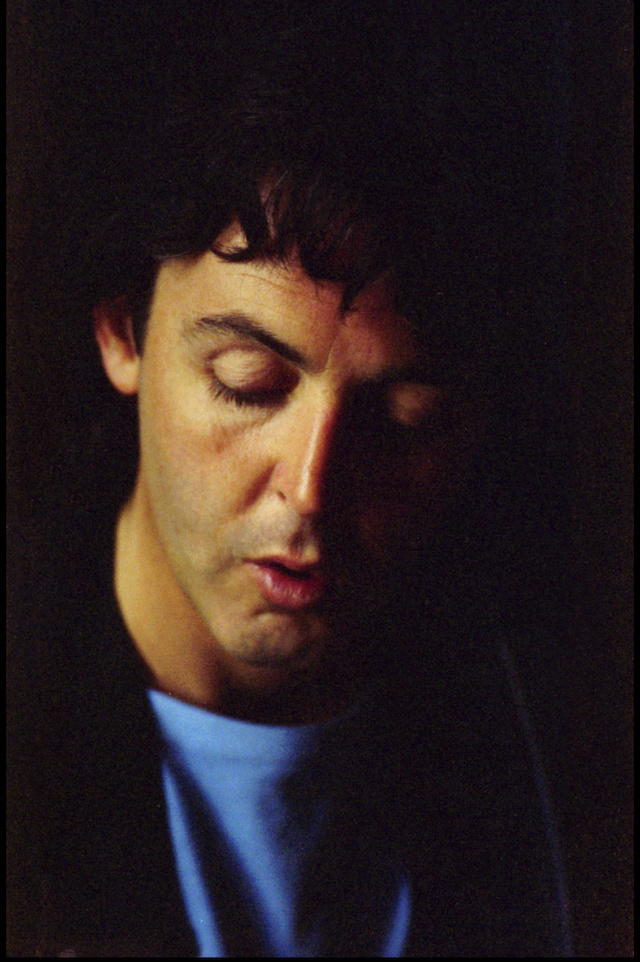

Paul, 1979, by Linda McCartney

Noisey: Hi Paul. Do you ever feel like you have nothing left to tell people?

Paul: Yes, definitely. There is one story for every situation. I do it in my live show. I’m talking and a story comes up. I think to myself, “If anyone’s been to my show before then they’ve heard all this.” There’s only one story about how I met John. I can invent another if you like, but everyone knows it wouldn’t be true. I always think to myself, “I’ve told this a million times.”

Is there a positive to all the documenting? Has anything recently ever triggered anything you’d totally forgotten? Or have we literally milked you dry?

That’s interesting, and it does happen. I enjoy it when it does. I did a poetry book a few years back. I had a reading coming up, so I asked my poet friend Adrian Mitchell, “What do I do?” He said just think of something to say about how the poem came about. I was planning on reading out “Blackbird.” I started to remember writing it. It was in the 60s when all the civil rights stuff was happening in America—Arkensas, Little Rock, and Alabama. I remembered that I had first started writing that song as something that I thought would give hope to the people going through those struggles. Now, I’d not thought about that in a long, long time. Now, when I do the song, I always remind people that’s what it was originally about.

You’ve been stupidly famous for over 50 years. You haven’t publicly shamed yourself, suffered a breakdown, wrestled with addiction, or even just mysteriously disappeared for a decade. How do you survive something as deadly and unpredictable as fame?

It’s something I’ve asked myself a lot. I think it all stems from my Liverpool family. They are very down to earth. Whenever I would go up there, it’s as if I’m not famous. I’m just “Our Paul.” It’s all, “Alright Paul, how you doing man? OK, great.” I got grounding from them. Once we got famous, you could remember that. You’re just an ordinary Liverpool person. Yes, it all spirals out into the fame thing, but as long as you remember who yo–

[At this point in our call, there were a couple of sudden thuds and bangs, and a small McCartney sounding yelp—then the line went completely dead. Obviously, after about ten seconds, I started to think, “Oh no, what if I just heard Paul McCartney die?” By 12 seconds, I was feeling the sadness of a world without him. I saw the news reports, the tributes, the Tweets, the respectful street parties in Liverpool, the content, all of the content, the gigs, and the widespread national mourning. By fifteen seconds, I overcame my grief, and selfishly started to see newspapers interviewing me about it all: “We spoke to the guy who was on the phone to McCartney when he snuffed it.” Pull quote: “I couldn’t believe it. One minute we were talking normally then bang.” Then my phone rang, and it was Paul again.’]

Paul: Sorry, I dropped the phone and all the batteries fell out… Anyway, I grew up with quite a good idea of how to keep things normal. I wasn’t always successful, but most of the time I was keen to keep it grounded. I go on public transport, I keep cool.

Have you seen fame swallow those around you?

Yes I have. That is what happens. That’s another way to keep yourself grounded, by seeing how fame goes for others. Once you’ve seen the “Do you know who I am?” syndrome in full effect, you know you’ll never do it yourself. If you do, then the minute you leave the room, everyone you were shouting at will just laugh and go “Fuck off!”

Have you ever mentored others struggling with fame?

There have been a few people I’ve tried to help over the years by chatting to them, but not always successfully. Some of them I could see were too heavy into drugs. I’d tell them to ease off a bit or be careful. But I wasn’t always successful, and some of them are no longer here.

Does it feel different being on stage now to how it felt as a teenager?

It’s different. You used to be unsure of what people thought of you. That is the basis of stage fright. You think, “They are going to hate me and something is going to go wrong.” In the early days, I used to get very nervous. I remember thinking about giving it all up one time in the early days of the Beatles.

The difference now is, I just say to my promoter, “Just stick one show on sale and see how it goes.” He calls back he says, “Chicago just sold out in 2 minutes!” That boosts your confidence. Now, I’m more confident that people want to come and see us play.

Is there anywhere in the world music hasn’t taken you that you wish it would?

China. I’ve never been to China. Lots of people have. I’ve never been. I quite fancy that. Maybe one of these days. It could be pretty cool couldn’t it?

Have you ever fallen out of love with music?

It’s always something I love. Before I called you, I was noodling around on one of my guitars. I’d pick it up and play a little something. Suddenly you’re writing a song and not just noodling around. That is the excitement; that you can magically craft something that never existed. That is very addictive.

Where is that moment of satisfaction? When you craft it? Or when you’re playing it onstage to thousands?

There are a few moments. The moment when you craft it is one. The moment you record it is another one. Then, when you play it for the first time to people. They are the three moments of satisfaction.

Paul, 1991, by Linda McCartney

What have you learned from your time on earth?

That’s a difficult question. The first thought that comes to mind is: don’t underestimate anyone. If you saw my Liverpool family, you’d think they were just a bunch of scousers. But once you get to know them, there are all sorts of hidden depths in there. One of my cousins—who was older than me—he compiled the crosswords for The Times, The Guardian, and The Telegraph. They have got to be three of the hardest crosswords in the world.

They sure are.

He’s just some scouse bloke. You’d never spot him in a crowd. You’d think he’s nobody. He doesn’t look like anything. But he is. That’s why I love talking to different people. I ask them “Where you from?”, “What you doing?” It sounds like I’m being nosey, but I just want to know. Because sometimes you find out the most amazing things about people. The world has taught me to never to assume somebody is nothing. You might be completely underestimating them.

What would you tell a sixteen year old Paul McCartney if you could?

Don’t go into the music business.

Wow.

No, I’m joking. What would I tell him? Be careful, son. Take it easy. Be true to yourself and enjoy it.

So, you wouldn’t change a thing?

You have certain regrets just like anyone does in life. Moments I look back on and think I wasn’t cool enough in that situation, or I wasn’t very kind to someone. But that’s life. When you’re growing up, you’re not always sensitive to people. But apart from that, I’d do it all again.

What scares you?

I suppose the way you can’t nail life down. You grow up thinking that if you learn enough stuff and get the right education then you’ll be able to nail life. I’ll know what’s going on. One thing you discover is that the goalposts are always changing. The rules change. The world changes. When that happens, you realize you still don’t have a clue. And it shocks you. You think, “I don’t have the information I need to deal with this.” That scares me.

I do that a lot. I think, “If I just read this one book… If I just finish this one project… If I just go running for three months… I’ll be bossing life.” I never am bossing life.

Then you read that book, you get that done, and somebody changes the rules. It’s this book now, it’s this thing now. The unpredictability of life. Other than that, I’m not too bad. I don’t live a fearful life.

Has the internet made your life better or worse?

I kinda like it. In music specifically, it had got very boring to do everything the traditional industry way. Releasing a record had become the worst part of making a record. You created it—a labor of love—you’ve played it as nice as you could. Then suddenly it was like you’d finished your exam paper and you had to wait for the teacher to judge you. I wasn’t making music to be judged; I was making it for the love of it.

I don’t know if I can even remember a pre-internet music industry anymore.

One of the funniest clichés about the old music industry was ‘going to Cologne.’ They’d always send you to Cologne, and they’d invite everyone from France, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, and Germany. You would do a series of interviews, and it was so mind numbingly boring. We talked earlier about having the same stories to the same questions? Well, you would do that all day long. “What is this song about?” I’d answer. [Affects German accent] “Hey, what is this song about?” I’d say the same thing again. I remember saying, “I’m never going back to Cologne.” The Cologne syndrome.

But in answer to your initial question, I like that the internet has made it an open game now. Anything that opens up the game is good. The Internet does that. Having said that, I’m not sure I would just ‘drop’ an album.

Would you ever get Snapchat?

Yeah! Sure! But I’m not technical. I’m barely technical with guitars. Someone tells me, “Hey Paul, I have an L130.” I have absolutely no idea what they are talking about. Could be a train for all I know. This translates to the computer and Internet world. I watch stuff on my iPad and take photos on my iPhone, but I’m not, you know… a gamer.

Do you think you’ll ever be a gamer?

I wish I had the time. But there is always something to do. Like this interview. If I didn’t have this interview, maybe I’d be gaming?

Did you learn anything from becoming a grandfather that you didn’t from becoming a father?

You just remember it all again. I suppose the thing is, your grandchildren are different from your own children. Time has passed. Now they are all on screens. Should kids be on screens all the time? There’s new stuff around that weren’t for my kids. So that’s what you learn from becoming a grandad… you learn how to operate a computer.

You said in one of the episodes of your new virtual reality documentary, that you discovered the meaning of life in Bob Dylan’s hotel room one night, and you wrote it down. The next day, you found the piece of paper and it just said “There are seven levels.” First question: Were you on drugs, Paul?

OK, first answer: Yes! I think that was our first pot experience. Yes! Answer: yes! Moving on.

Second part: has your interpretation of the meaning of life changed since then?

I never quite knew what I meant that night, but the weird thing is, I’ve run into people who have said they got something from it. They start going into scriptures and ancient texts and stuff, and apparently there are people who say that, about levels. All I know is, it seemed very definite to me at the time. And because it was my first pot experience, my overriding concern was telling everyone back home. You know how you do that? If you do something great, you can’t wait to tell your mates? Like, “I’ve just been there!” or “I’ve just met this person!” or “I’ve just been to Disneyland!” Well I thought I’d cracked the meaning of life, so I couldn’t wait to tell everyone back home. Who knows… Maybe “There are seven levels” is right. It certainly seemed very right that night.

You can follow Joe Zadeh on Twitter.

Pure McCartney is out now.

More

From VICE

-

Thinkhubstudio/Getty Images -

Screenshot: Kwalee -

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki -

Screenshot: Capcom