It’s more than 90 degrees on the Saturday afternoon of Coachella, but leave it to Michael McDonald to not break a sweat—though the heat is the least of his concerns. In a few hours, the Doobie Brother, Steely Dan collaborator, and prolific songwriter and solo artist will take the stage for his Coachella debut, joining Thundercat for a surprise performance of their Drunk collaboration with Kenny Loggins, “Show Me the Way.” The tent will be packed with peacocking bros and spliff-wielding jazz heads alike, and the announcement of his name will only send more running. Solange, Moses Sumney, The Gaslamp Killer, and, perhaps most nerve-wrackingly, McDonald’s 25-year-old daughter Scarlett, watch from the sidelines.

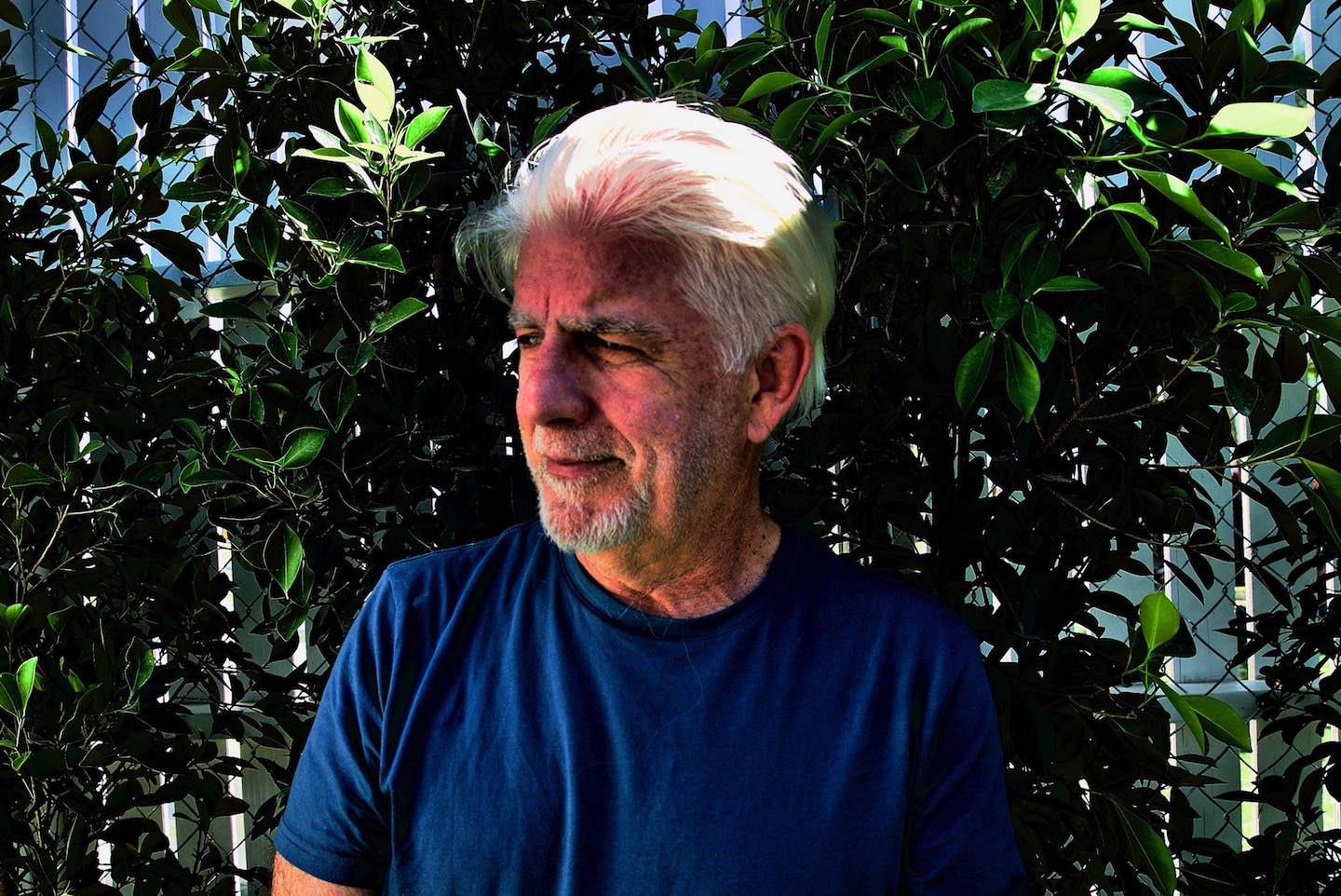

But right now, lounging on a couch in the shade, the 65-year-old is, of course, the smoothest. He removes his Topa Topa Brewing trucker hat, running a hand through a shock of dramatic yet unruffled white hair and extending the other forth in greeting, like the captain of a ship—nay, yacht—returned from a satisfying day at sea.

Videos by VICE

What is yacht rock, really? Is everything yacht rock? The go-to answer, typically, can be found in the term coined by the eponymous mid-00s web series lovingly spoofing the late 70s/early80s blend of soft rock and smooth jazz that McDonald pioneered alongside the likes of Loggins. Though easily mocked and at times critically derided for its deeply earnest “sophomoric musical exercises” (as McDonald himself puts it), the genre’s distilled R&B and unapologetic tenderness has endured beyond the naysayers, embraced by everyone from Thundercat to Solange and embedded in the sound of rising acts like Khalid. We sat down with McDonald to discuss his enduring influence, playing Coachella, his new album, and staying free in the face of Trump.

Michael McDonald performs with Thundercat at Coachella / Photo by Christina Craig

Noisey: How did the collaboration between you and Thundercat come to be?

Michael McDonald: Kenny Loggins had reached out to Steve Bruner, Thundercat, after he had heard an interview where Steve mentioned Kenny and I. Steve showed some interest in writing with us, so he called me and I really didn’t know what to expect. But when I met Steve and I heard some of the stuff he had been cutting for the new record, I really was jazzed, and I became immediately aware of his past stuff. He’s an amazingly talented kid and got a great musicality, so I just wanted to kind of be a part of it on any, whatever level. We wrote the one song, and I’m hoping to write some stuff in the future. I was thrilled that he asked me. I did the Hollywood Bowl with him at the Flying Lotus festival. I love playing with this band because they keep it very simple. It’s very much a live experience, you know? Where the song is kind of a template, and the musicians bring whatever they’re gonna bring to it in the moment, you know?

What do you think about the yacht rock revival that’s been happening in recent years? How does it feel to see your legacy being embraced by a younger generation that way and kind of repurposed, and now participating in that as well?

It’s very flattering, really. I really enjoy the chance to get out and play with the younger artists and kind of—we had been working the whole time, which I think in a way was a good thing. The only way you stay in shape playing is if you play. And so I’m more glad now that I did that through the years, even though I was just playing casinos and whatever we were doing to stay busy. And that’s the level I’ve always enjoyed music on, is just being able to play. I don’t know if I’ll ever enjoy what I do as much as I did when I was 13, 14 years old playing crappy clubs with no air conditioning, but it was a thrill. I was getting to play with older guys back then. This is kind of the same kind of thing but in reverse, for me. Getting out and playing with the younger guys, and getting to play with really great rhythm sections. I guess all I’m saying is that I’m glad I kept busy in the meantime. I would hate to have to come out of mothballs to do something like this, you know?

Does it feel vindicating in a way to have your work embraced like this and to be involved in these new collaboration, in spite of past critics?

Yeah, it’s thrilling and vindicating. What I have to remember, and what I think is a good thing, is that I’ve been around long enough in the music business to know that everything is seasonal. And this is wonderful. It seems like a lot of things that are happening to me later in my career are things that I wouldn’t have dreamed would be happening if I would have looked back. I’ve been working lately with guys that are my own age—you know Steely Dan and the Doobies and stuff. When I’m on stage with them I kind of get taken by the feeling of, did I ever think that when we were in our 20s that we’d still be doing this in our 60s? I don’t think I would’ve bet on that. As a lifestyle, as a culture, I think as a kid I was one of those kids that didn’t feel like I necessarily had a place in the high school strata, social strata. I was always kind of one of those people that walk in a room thinking, “How do I make these people think I’m OK?” You know? So I found in the music culture it was much more open, and people didn’t judge you by the same criteria that they judge you in a normal society. You just kind of bring what you bring to it, and you participate on whatever level you can find to participate on. You’re allowed to do that.

Why do you think your music is being embraced or revived by these artists now, as opposed to, say, ten years ago?

I think a lot of that is each generation tries to separate itself from the generation before. I remember a friend of mine I was writing with saying to me, “Yo man, with all due respect, you need to be more 80s and less 70s,” and I remember thinking “God, I’m already old.” And this is the 80s! So now, when I see radio stations that are like, nostalgic 80s radio stations, I laugh because, shit, I was already old in the 80s—much less now. But it takes about a good 30, 40 years for people to all of a sudden rediscover what you might have been doing back then.

This goes beyond the trend cycle though. Specifically, there are real overlaps in the bones of the music of artists like you and Thundercat—or even Solange, Khalid, Frank Ocean. To me, it seems more like a sonic aesthetic than a generational rediscovery.

I remember back in the 70s, when the Doobies were touring a lot, having a conversation with some of the guys in the band about music that we didn’t necessarily… that we secretly loved, you know? I grew up listening to a lot of Rogers & Hammerstein, Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, Nat King Cole, and songwriters like Cole Porter. And I remember making the statement that it’s a shame songs that were written by Gershwin, and Cole Porter, and writers like that, you’ll never hear them on the radio again probably. It’s not the kind of thing that today’s audiences would even identify with, you know? And yeah, there was a certain level and sophistication of pop music that seemed profound, really. And sure enough, a year later, Linda Ronstadt does the Nelson Riddle album. And it was a huge hit. And it just goes to show you, you can’t discount anything. With time, people are willing to rediscover it somehow and reinvent it, maybe.

“You can’t discount anything. With time, people are willing to rediscover it somehow and reinvent it, maybe.”

What do you think about the term “yacht rock”? What does yacht rock mean to you?

I thought it was very funny from the get go. And for a while I watched as many episodes [of the web series] as I could. I always thought it was uncanny how everybody was portrayed, because in some weird, psychedelic way, it kind of hit on everybody’s personalities in some strange way. But, without knowing any of us. I think what it means is that it was kind of a making fun of the smooth jazzy kind of style that a lot of our music was. I’ve often said that we used to try to put as many chord changes in one song as we could, just to see what we could get away with. It was kind of, in our own way, sophomoric musical exercises, and I think that’s what they were referring to. You know, enough of that already. But there would be some world or some boat floating out in the vast ocean where we would be confined for the rest of our lives, as a public service! [Laughs]

Are guys like Khalid or Frank Ocean yacht rock, in your eyes?

No! Not at all. And like you said, I think in a way that’s kind of validating. Because I never got that they were; I was surprised when Thundercat said, “Oh man, I grew up on you guys.” ‘Cause, you know, he does such a good job of reinventing R&B that I hear a lot of influences, and the last thing I would have guessed would be that me and Kenny were in there somewhere. So I was flattered. But all these guys, the kind of neo-soul thing, it’s right up my alley, I like that kind of harmonic, somewhat kind of more sophisticated harmonic sound sensibilities. For a while, in the 80s everything was like, it’s gotta be kind of primitive. I mean the punk rock thing was a real backlash to the 70s. But like I say, every generation has kind of their backlash reaction to the generation before it. Until that got ridiculous, you know? People worked too hard at trying to be rock ‘n’ roll, and I don’t think that any of us will ever return to the era when people were just discovering this stuff like Chuck Berry, and Bo Diddley, and those people. They weren’t trying to be anything, they were just being themselves. They were just talking their own language. And I think almost all of us since then have been trying to reinvent them in some form or fashion. But I don’t get that from these young guys. When I first heard Thundercat’s stuff I thought, “Man, this is so original.” A lot of his ballads to me had such a beautiful harmonic, almost classically Hispanic feel, or like Brazilian kind of feeling. I don’t think he does that intentionally or anything. It’s just I think those are his influences on some level. And I think we all kind of did that growing up.

Michael McDonald performs at Coachella / Photo by Christina Craig

What else is coming up for you?

I got a record coming out in September, and we’ll be touring all summer. This record is a different kind of record for me. It’s a very eclectic record; there’s no real fixed genre to it. And I think the reason for that is it’s about eight years in the making. I went off and did Motown records, and in the meantime I was always cutting demos because I was a songwriter. And I had a studio with a friend of mine who’s a drummer and a great engineer, and I would sneak in at night or on days off, for him, and try to cut as many demos as I could for songs I was hoping I’d get other artists to do. But he would go in and redo the drums and put real bass on it, real guitar on it. So about five years into this he goes, “I’ve been working on some of those tracks a little more, I wanna play them for you.” So he played me this stuff and I was utterly surprised at how good it sound it. And he says, “I think we should do this record.” It’s got kind of a weird, multi-textural feeling to it. Some of them are kind of rock, some of them are R&B things you would normally expect. It’s a very wide open kind of concept record. But it’s the first original record I’ve done in probably ten years, 15 years.

So it’s a concept record?

Well, the concept is just all the different places. It’s more of an album of reflection. All of the songs seem to do with just the normal kind of thinking that we all do about personal conflicts, personal identity, the society around us as it takes shape. There’s one song, called “Free a Man,” and it’s basically just the conversation that we’re all having right now, about what it means to be—what does the Constitution really mean? How does our government really serve us as a population, as a humanity? What does it mean to be gay, what does it mean to be black in America? What does it mean to be a kid that has to grow up under the pressure of a society that tells him that religion and finance are really what life’s all about? And then they get to that age where that—like it did to all of us—scares the shit out of you, and you have to rebuild your whole thought process so that you can live with yourself in a world that would tell you otherwise, would tell you that there’s something wrong with you for not being in line with striving for monetary success and adhering to certain ideologies politically, or religiously. What does it mean to actually be free? To be a free person living in a society that claims to be free but really isn’t. And the chorus of the song is pretty simple: “Free a man and love will follow.” The impetus on us as a humanity is that we have to really redefine freedom all the time and raise the bar of what freedom is so we can actually get around to knowing what love is. Because religion, governance, occupations do a really good job of killing the possibility that we’ll really understand the primary job of being human, which is to experience love.

“Religion, governance, occupations do a really good job of killing the possibility that we’ll really understand the primary job of being human, which is to experience love.”

Has any of your work actually tackled the subject matter this overtly before?

In some ways it’s the most honest record I’ve done, without trying to be too honest—because that’s kind of a rabbit hole too.

What is it about you and where you are in your life now that makes you feel like you can take that on versus in the past?

I love the perspective that comes with age. I don’t like the physical aspect, but I’m a happier person than I’ve ever been, and I’m a more accepting person than I’ve ever been. I’m more likely to be grateful for what I got these days than frustrated by what I don’t have, or what hasn’t happened, or what I didn’t do in the past. And I think that just comes with time and staying one step ahead of destroying yourself as you live your life, because all of those things can take a toll on your life as a human being. So this record’s just about seeing the blessings in disguise and understanding that probably one of the most important things we’ll ever experience in our lives is learning to forgive, learning to move on, and learning to not blame. And learning to accept other people’s version of what it is to be free, and to be human.

Can we expect collaborations from other folks on your record?

I always want to, and then the problem is this day and age, when you ask somebody, it gets very complicated legally and all that. And everybody’s doing a record, so it’s usually bad timing. I wanted to do a couple duets, but the people that I thought really might be great for it weren’t available. I wanted to do something with Brittney from Alabama Shakes, and I thought it really was the song that would have been perfect for her, but it didn’t work out. I don’t even know that she got word of it. I’d like to do something with Frank Ocean, you know, and I love working with Thundercat, and I’d love to do more with him. If the opportunity arose on the next record, if I could get something going with him and pull him in on that project that’d be great.

Have you ever met Frank? Do you know him?

No, I don’t. But I’d love to do something with him. Oh gosh, there’s so many people. I’ve always been that way. Even back in the 70s, I was working as a studio singer and I had the opportunity to play on a lot of other people’s records. I always enjoyed that.

I think one of your strengths has always been your collaborations. Talk a little bit about what collaborating brings out for you creatively that you can’t do on your own.

Yeah, I find [solo work] harder. Collaborating I like because the other people kind of encourage you to move forward. When I write alone, I can write a song for five years, and I mean that literally. Some of this stuff on this record, I cut the demo eight years ago, and I was still finishing the lyrics while we were mixing, and that’s because on my own I can get a little frustratingly unsure of myself. You go down the rabbit hole.

Is that a perfectionism thing?

I don’t think of it as a perfectionism thing, I think of it as a fear of it not being as good as it can be. And I guess that is a perfectionism thing. It’s a neurosis for sure, you know? But deadlines are good for that; they make you finish something. This record, unfortunately I didn’t have a deadline so it lasted way too long. But I’m hoping for the better. It’s done, and I’m pushing it off, out into the world. And then I’m really looking forward to jumping into some new projects that I’m hoping will be a lot more simple and go a lot quicker. One of the best records that I’ve had the most fun with was a record I did literally in two weeks. Wrote the songs, recorded ’em, mixed and mastered the record, literally in two weeks.

Which one was that?

It was a Christmas album for a Hallmark label. The guy that was supposed to do it, dropped out. So they called me and said they were looking for somebody to fill this year’s Christmas album that we do every year. I said, sure, and they said the only trick is it had to be done in two weeks for us to meet our release date. And I said I’ll try, and we literally pulled it off, me and this guy that produced this record. And it was just he and I and I played all the instruments pretty much. We had some guys come in, horn section and stuff, but for the most part it’s just he and I playing the tracks. We had some choirs, but miraculously we were able to do the thing in a short time, and I never had more fun. I wish I could do them all that way.

Are you nervous at all to be playing Coachella?

Little bit. The fact that I relate to the band and what they’re doing is all that matters to me. I can get up and play with them and I know what they’re doing, so that’s all I gotta do just keep instep with them. But you know to me the whole thing in this music business has always been I’m a combination of things; I’m not great at any one thing. I’m not a great keyboard player, even a great singer. I’m not even a great songwriter. But I do three of ’em, and once in awhile the combination hits a certain chord, and I’m always looking for that: How do I combine these things to pull it off in the moment?

Do you think our cultural and political climate has anything to do with why your music and yacht rock in general are being embraced again right now?

Yeah. Music has always served a lot of purposes, and it’s just like painting. Every new movement has brought its ire, and every old movement has had its set mentality. But I think a lot of times people, when they look into music in times like we’re in now, they’re looking to escape and into the beauty of something, so they tend to lean toward things that are more musical. Maybe I’m overanalyzing it, you know, whereas when things aren’t as bad as they can be, sometimes people want to point out what’s wrong with the world more, because you have the freedom to do. Because nobody’s gonna come and arrest you, or it’s not so bad, so you just don’t even want to think about it. We’re in scary times right now. The world around us is imploding, but that’s always been the case. We just kind of forget that, but society is one of those things where you always think, could it get any worse? And it’s like, be careful what you say, because it probably will. But at the same time it’s getting better, and you gotta step back enough. And sometimes music allows you to do that, and go wait a minute, there’s other perspectives to have here. And I think people tend to look for one or the other, and I think sometimes we get overly negative when we can afford to, and we look for the positive when it looks like things suck so bad that you wanna find anything that gives you hope.

Photo by Andrea Domanick

It seems like you’ve always been able to maintain this place of this tenderness, and gentleness, and vulnerability. What’s allowed you to continue to tap into that?

It’s funny because I’ve never been too much of a topical, like what’s in the news or what’s politically this or that. Ideologies, or anything like that, even social ideologies, because I always felt like the real conversation was just, how do I remind myself what being a human being is? Because I haven’t really found anything that makes me understand what I’m doing here more than loving someone else, learning to love myself. Because there’s really not too much else that makes a whole hell of a lot of sense. Cause we’re all gonna get sick and leave this world. It’s a short ride. So if you look at all of the things you could possibly accomplish while you’re on this physical plane, not many of them really matter, other than the love that you share with other people. That topic always comes up for me, and I can’t really think of anything else that is as important to write about. Maybe to a fault.

Maybe that’s needed though. It’s an easy way out to not do that.

Yeah, in most real arguments, I’d like to say I’ve written songs and I take it to the streets about such things. But when you get into the argument nowadays—I have so many friends who are just so intense about what’s going on in America, and suddenly, I’d go right there with them, but you know, I suddenly realized, I’m just drinking the poison hoping they’ll die. Because after a while, I’m carrying a bat but I’m hitting myself a lot harder than anyone else. And what’s the best thing I can do with the way things are and the people that are in charge in this moment. It couldn’t look worse to me, but all I can think of is pray for the sons of bitches and hope that they have an epiphany along the way. It ain’t lookin’ too good, but that’s what I would hope for. Me sitting around criticizing them, I can do that to a certain point, and we should all resist this movement which is towards dehumanizing people based on their religion and their sex and their sexual preference. We can’t go back there. People think that’s what makes America great; it’s just such bullshit. It took things like World Wars for us to see what was wrong.

“I always felt like the real conversation was just, how do I remind myself what being a human being is?”

How do you see music responding to all of this? Because usually with these political shock events, you see music take a turn. You know, the rise of punk, the rise of something else.

Music has a very big role in forming society and culture. You know, awakening culture to what the society they’re actually living in. And that’s the reason I think arts should be kept alive. We need to pull art into the fabric of our culture because it tells us who we are. It exposes us to ourselves. That’s what really makes us human in the end, but we gotta be careful, it’s a stage that this side of society, we’re gonna start arresting journalists and artists. I’m waiting for that any day now, where this administration starts arresting journalists. And when that starts happening, it’s the beginning of the end, as far as this country being anything close to freedom. How anyone doesn’t get that you can’t ban a religion or a race of people and call yourself a free country—it stops right there, it ends in that moment. So, that should be self explanatory, but apparently not.

Do you think that music is something where we’re gonna see people retreat further into as an escape, or do you think it’ll be a vehicle to catalyze change?

Hey, I hope it’s the latter. Not that music is the end all. Journalism has a bigger part in that, I think, because it’s the literal conversation. Music is more of a metaphoric conversation in many cases. Whereas journalism is the literal conversation that has to say. And seemingly more and more a great risk. I hate to say that, but that’s the scary part about what’s going on today, to me.

I hear you. Is there anything else you’d like to add?

I’m just kind of taking it as it comes, pretty much and hoping that when it’s over, whatever these things happen in seasons, and right now I’m enjoying this one, you know?

Andrea Domanick is Noisey’s West Coast Editor. Follow her on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

Collage by VICE -

Screenshot: Electronic Arts -

(Photo via Sonsedska / Getty Images) -

Screenshot: Ubisoft