My mistake was hoping that A Way Out would be good. That it would deliver on its ambitions as a piece of interactive, collaborative narrative. I didn’t expect that its storytelling would or could rise to the level of the crime movies that so clearly inspired it, but I hoped that it might work successfully in their shadow and make you feel, if only for a moment here and there, like you and your partner were participants in prison break and outlaws on the run.

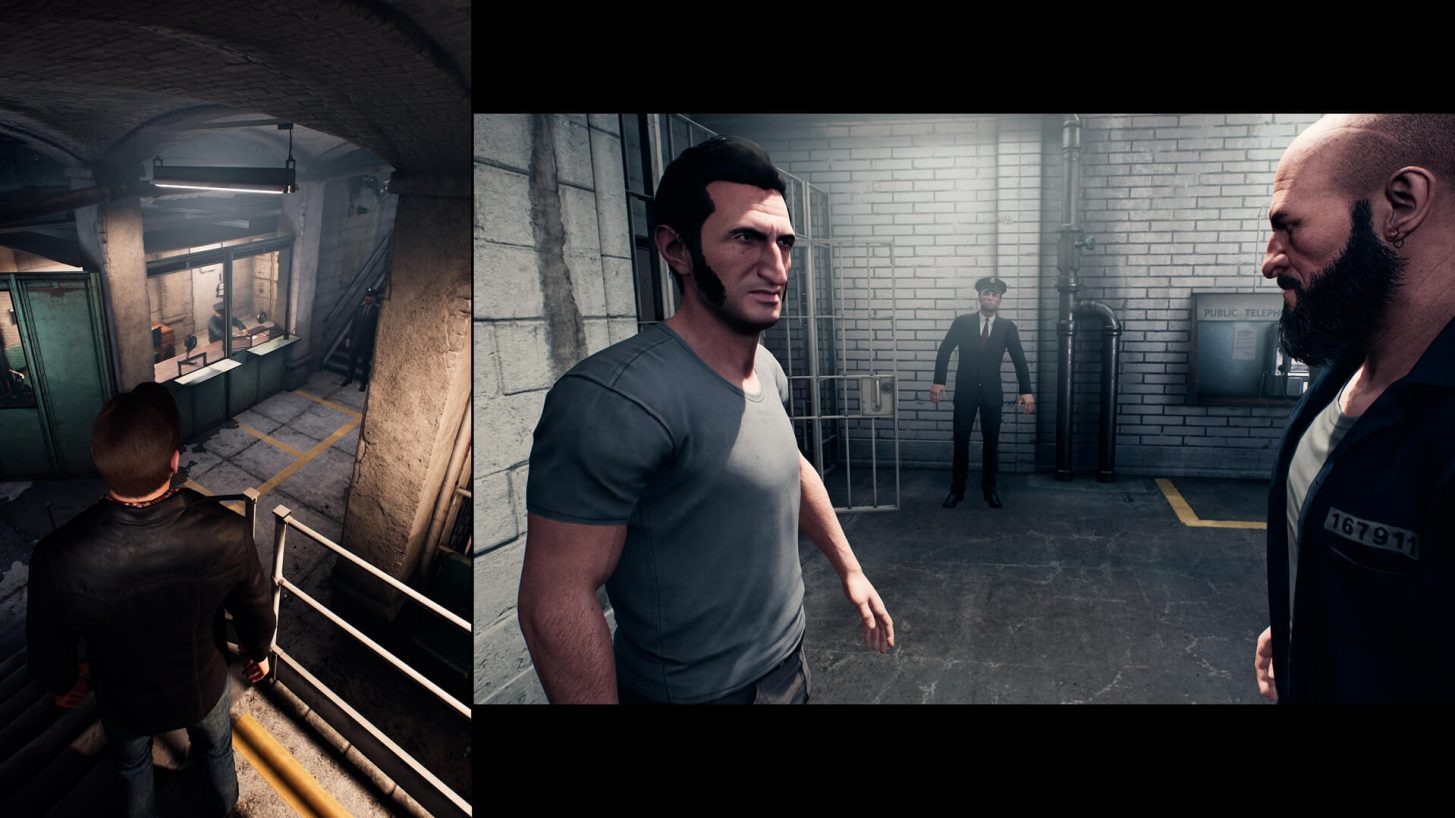

The entire game is set-up to evoke that feeling. It unfolds via split screen, with you and your partner each controlling a different character on one half of the screen. You share the space, work together to solve puzzles (often meaning that you tab buttons together to move an object, or you pass objects from one character to another). The entire thing occurs in a version of 1970s America that owes a lot to familiar cinematic influences. On paper, it’s exactly my kind of game.

Videos by VICE

But the truth is that A Way Out is really more successful as a piece of camp, because it is as camp that all badly-written lines that are compounded by bad readings and lifeless animations go from being engagement-killing stumbles to beloved laugh lines, in the tradition of literally any David Cage character affecting a regional accent. The “square peg, square hole” nature of the—puzzles? obstacles? plot devices?—become characters in their own right: the prison toilet with no pipes, the hardened prisoner who starts a brawl because he’s told that someone insulted his mother. What A Way Out really reminds me of is an RPG campaign whose narrative has been lovingly preserved in journals and notebooks, waiting for the day when one of its creators will turn it into a story. This is the interactive-community theater version of that story.

And when I was watching other people play, I saw and enjoyed that version of the game. Watching Austin and Patrick play the act of A Way Out on stream the other day was the most I’ve enjoyed the game, both because their heads were in the right place with the game and there was a Twitch chat full of people sharing the same hallucination.

The problem is that’s not the experience I had earlier in the week, when my girlfriend and I were playing it on the couch. This is far from the first game we’ve played together, and God knows we’ve enjoyed our share of campy and B-grade genre trash. But A Way Out slowly let all the air out of the room to the point where we were both playing it solely out of obligation. The long silences the middle of conversations, while particular lines and animations queued up, felt interminable. Every scene had a frozen, dioramic quality, but without any of the detail that makes a location into a place. And we were actively discouraged from exploring what detail and characters surrounded us by the shabby and insulting minor characters.

One of the first conversations we had with another prisoner, for instance, was about how he heard voices. As he rambled on in his motormouth way, doing a halfhearted impression of an offensively stereotypical notion of psychiatric distress, it was clear that this was a stock character who existed only to exchange this pitiful, canned dialogue with a player. Again, it’s the kind of move that a juvenile RPG game master makes, rushing a half-conceived notion of a person in front of a player-character because they wanted to explore something off of the path that is supposed to take them through the scripted narrative.

The reliance on off-putting stereotypes is reflexive: The storyteller is trying to justify why further exploration of this character is impossible or undesirable, but also thinks that a convincing character needs to have some kind of readily observable “thing” that defines them and implies a life beyond the confines of this one particular story. This is a regrettable but forgivable and correctable mistake when you’re a teenager sitting around a table with friends, or in a creative writing class. It’s pitiful when it happens in a major video game release.

The major characters are not that much better. The two prison escapees are a kind of taciturn Charles Bronson-movie character named Vincent and a jangly, nervous Pacino-like character in Leo. Each comes across as a decent-if-flawed “man gone wrong,” sharing both a desire to put things right for their family on the outside and settle a score with an arch criminal who crossed them both.

Trouble is, the writing and voice acting combine to make them both, but especially Leo, come across as profoundly weird dumbasses. It’s like someone tried to make Octodad into a gritty crime epic: The story is asking if Leo can ever be reunited with his wife and get revenge on Harvey, the violent thief who double crossed-him, but all you can think about it is whether someone is going to point out the fact this guy is obviously a space alien. Endearing in his strange, inept way, but profoundly strange as he puts on different accents, fixates on random objects, and occasionally chews on words like he’s about the launch into a classic stoner ramble about the arbitrariness of language, the relationship between object and meaning, and how weird he feels, you guys.

And again, in the context of watching people play, with other people, all this narrative and performance malpractice adds up to something much greater than the sum of its parts. But when I was playing it, at night after work with my partner, I found myself hating these unconvincing meatheads and the barely choose-your-own-adventure playable sequences where they lumbered around the world looking for the next thing that they both needed to work together to trigger. I wasn’t transported into the game’s world; rather, it felt like it was intruding on mine.

More than anything, A Way Out left me wondering if the moment for games like this is passing, or if there’s simply more to making them than may first be apparent. Would I now find Heavy Rain as cringe-worthy and grating as I find A Way Out? Or is there something about the way a game like Heavy Rain or Fahrenheit builds tiny, empathetic connections between player and character around the mundane that helps overcome crap writing, conventional cinematic inspirations and aspirations, and roll-of-the-dice voice acting? Why is Life Is Strange surreally haunting while A Way Out feels, at its very best, like a network TV pilot that never finished post-production?

A Way Out might be perfectly suited to its time: There’s never been a better time for a game to wallow in its half-baked contrivances and unconvincing version of reality, because it’s never been easier to share that with friends and peers and marvel at all the ways a game can make the familiar seem magical and absurd. But amidst all that, you can tell it wanted to tell a story, and put you in the shoes of its heroes, and get you talking with your partner about what you wanted to do, and why. It wanted to tell a story with some stakes both for you and your character, and instead it’s a game of looping gifs and laughable one-liners. It might be bad enough to be good, but it’s nowhere near good enough to be great.

More

From VICE

-

Collage by VICE -

Screenshot: YouTube/Assassin JorRaptor -

Screenshot: Warner Bros. Games -

Screenshot: Ubisoft