A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

The situation with the tariffs is pretty weird, isn’t it?

Videos by VICE

Whatever your opinion of the ongoing trade war between the United States and China, the fact of the matter is, it represents something of a proxy battle over where American interests stand in the world of manufacturing.

And computers are no exception. The Mac Pro, a product that has in recent years been produced in the U.S., was recently rumored to be moving to China—but after the president said he would not protect the company from tariffs, Apple suddenly changed its tune.

We closely associate modern computing with Chinese production apparatuses, to the point where it makes no logistical sense to slap a “made in the USA” sticker on the box. But just a few decades ago, a lot more computers were assembled in the U.S. Why did that change?

As with a lot of modern tech tales, a story from the past has a lot of answers—in this case, the tale of a company whose boxes literally screamed Americana.

Let’s discuss how globalization disrupted Gateway 2000, once the largest direct seller of PCs in the country.

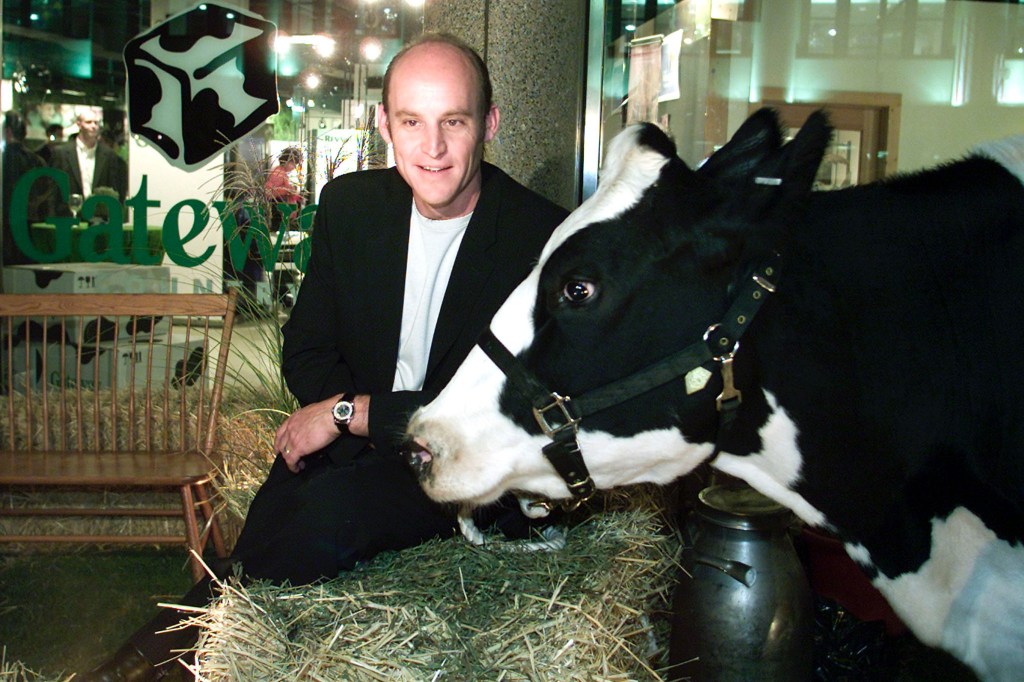

“So I said, where did this logo come from? And he said, ‘It’s spots on a cow.’ He said, ‘We started in South Dakota and Iowa and people said, how can there be a computer company in the farmland of America?’ And now there is one in the farmland of America that happens to be in Ireland.”

— President Bill Clinton, discussing Gateway 2000’s expansion into an Irish factory in a 1998 news conference in Ireland. Yes, Gateway had a factory in Ireland, which it opened in an attempt to bring its computers to the European market. It wouldn’t be the first time the company outsourced—not by a long shot.

If a company like Gateway 2000 existed today, it would be hailed by politicians as an example of American ingenuity

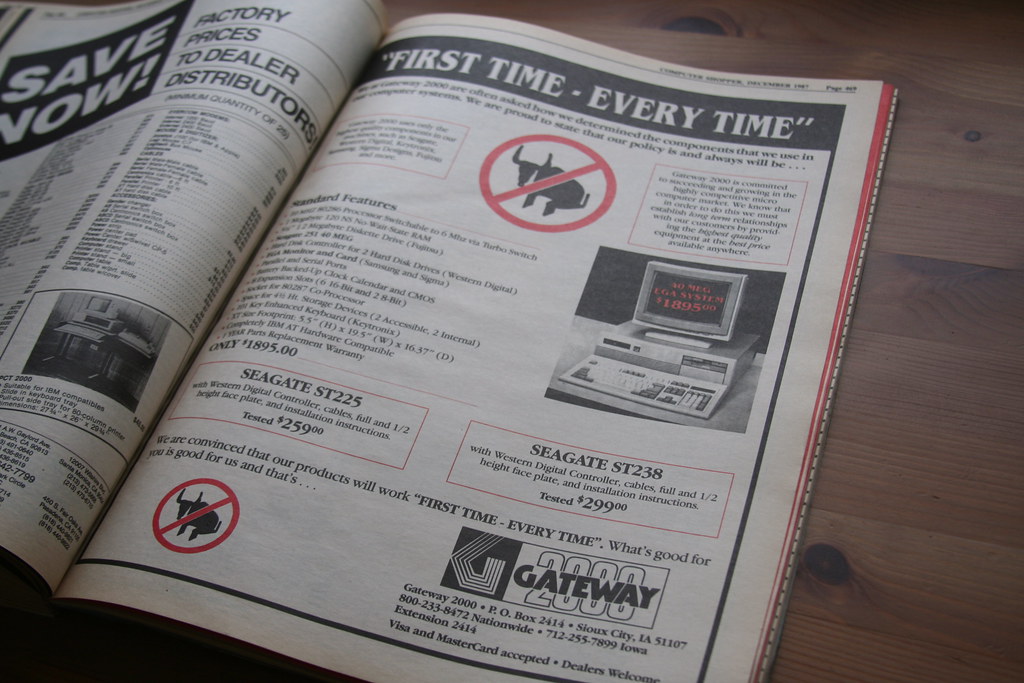

The story of Gateway 2000 is one I’ve long been interested in, and touched on in the past, in the context of a piece on Computer Shopper, a magazine where it frequently advertised.

But, given the tenor of the recent trade talks, its story is particularly telling because it highlights some important questions about globalization.

If a company like Gateway existed today, its factory would be the kind of place that the president would visit just to highlight the fact that someone was building computers in the U.S. and having a lot of success at it—just like Bill Clinton did in 1998 … in Ireland.

Here was a firm that, throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, kept overhead low and profits high by bringing jobs to a part of the country that might have struggled to attract a high-tech firm otherwise. It was homegrown, and founders Ted Waitt, his brother Norm, and Mike Hammond did something impressive: Early on, they kept it local, taking advantage of the community’s unique resources, and even underlining that point with their marketing.

The company, at first, eschewed things that other competitors deemed necessary. It was located far from other centers of tech-field activity of the era, like Texas and Silicon Valley, and it didn’t function like those companies, either. Initially launching out of a barn, it later moved to Sioux City’s Livestock Exchange Building, meaning the firm had literally displaced cows to build computers. (Later, it moved to its own facility in North Sioux City, South Dakota, just across the Iowa/South Dakota state line.)

According to the corporate history database FundingUniverse, rather than doing market research, they built their computers based on Ted Waitt’s specifications, believing that common sense was the best way to spec out and price up a computer. (His instincts were often correct.) And rather than bringing in a marketing team to publish its first big ad, Waitt designed it himself—coming up with the iconic “Computers from Iowa?” line in the process.

The ad approach was so unusual that the company became downright famous for its print ads. While, admittedly, it’s hard to get a hold of a full array of Gateway magazine ads in 2019, it’s worth noting that their print advertising game was possibly some of the most ambitious being produced during the era—in any industry.

Gatefold spreads? Over-the-top photography? The founder seemingly in every photo shoot? Gateway knew that it was in a field where its competitors hadn’t gotten past product shots, and there was serious concern about the small guys being fly-by-night companies. Putting the brand out front allowed it to differentiate itself from the rest of the herd in 1992.

By carrying itself like a big guy when it was still a small guy, eventually it became a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Gateway, within just few years, was on a massive hot streak, seeing its mail-order-only sales soar. By 1991, it was the the top company on the Inc. 500, with the article about the win noting that Gateway had managed to stand out in an incredibly difficult business—to the point where the story trailed the owner of a competitor who felt compelled to travel nine hours to Gateway’s headquarters to investigate the suddenly overwhelming competition.

In the article, Waitt pointed to the folksy style and the inexpensive locale, of course.

“People try to make things more complicated than they are,” Waitt told the magazine. “There’s no magic formula. It all revolves around the way we do things.”

Gateway was notable in that, like Dell, it leaned hard on the ability to customize computers. The company did not have a place in stores at the time, so much of its sales took place via mail order. And by using mail-order, the company could give users specific say in what they wanted for their laptop or desktop.

However, the way it did things would quickly run into challenges. Around 1992 or so, the company’s down-home approach started to buckle a bit under the weight of its fast-charging success. The mail-to-order business started to face challenges with shipping its computers on time, and despite having more than 1,400 employees at the time according to Bloomberg, there would be delays of weeks and major quality control issues.

You know a great way to solve challenges with delays and quality control issues? You outsource so you have more access to human capital resources, though at this juncture in its history the company didn’t do that. It faced challenges in finding enough employees in South Dakota, but it kept those workers on the job. (Later, it built other regional factories in other relatively low-cost-of-living cites such as Hampton, Virginia.)

Eventually, though, its values—and leadership—changed.

Gateway’s many experiments—including its brief ownership of the Amiga brand

At its height, Gateway had an effective business model: highly custom PC clones sold through the mail and promoted in magazines, with an audience that attracted enthusiasts and small businesses.

But this model had weaknesses. For one thing, it gave Gateway no real way to expand into international markets; for another, it meant that the company had no retail presence to speak of; and for a third, it meant that any competitor could come in and disrupt it by finding a way to lower prices.

But the company’s attempts to solve these problems arguably destabilized the business over time.

The firm conducted a number of experiments, two of which it was well-known for. The first, the Gateway Destination, was a television-style PC at that it started selling in 1996, at a robust price point of $3,500. The TV screen was a 31-inch monitor—an absolutely massive size for 1996, because it was a giant CRT. While the device wasn’t particularly a success, it was an influential design and an early attempt to bring computers to the living room.

Another influential not-quite success was the company’s specialized Gateway Country stores, which both predated and possibly inspired the later Apple Stores. The mail-order showrooms were interesting to observers but ultimately proved a dead-end for the company, as the stores struggled to have an impact on the bottom line. Eventually, the company started stocking computers directly in the store.

And its moves into the European market, which it eventually left entirely, played a small role in perhaps one of the greatest head-scratcher moves in computing history: Gateway’s 1997 acquisition of Amiga, a merger that on its face sounds like it shouldn’t have happened.

But the truth was that the move was a defensive one, made not because Gateway was particularly interested in Amiga, but because Gateway, which started off by building PCs from off-the-shelf parts, had little in the way of patents. As Ars Technica notes, by getting access to the Amiga’s patent library, it effectively discouraged IBM, which had grown frustrated with the competition it had unwittingly created for itself, from attempting to sue the clone-maker.

Gateway’s attempts to push the Amiga forward—including by switching the basis of its operating system—were met with skepticism from the fan community, and internally, hit a brick wall when Jeffrey Weitzen, a former AT&T executive, replaced Waitt as CEO. In the end, Gateway owned Amiga for just a few years, and sold it off—while keeping the patents that made it valuable in the first place.

It creates an interesting what-if: What if Gateway embraced the Amiga as an Apple-style niche? Would Gateway be around today? Hell, would Amiga be around today?

How Gateway strayed from its down-home roots

All of these things, in retrospect, come across as rearranging deck chairs. By the late 1990s, cultural shifts with both Gateway and the computer industry in general made its original pitch feel a bit less compelling.

One issue was that the company moved its headquarters to California, which permanently shifted the corporate values of the firm. (Around this time, Gateway dropped the 2000.) Waitt eventually admitted the move away from South Dakota was a big mistake.

“It was much more money-oriented. It was much more short-term oriented,” Waitt told the Sioux City Journal in 2007. “And there was different leadership in place at that time that incentivized that—and changed the company, I think, indelibly.”

(Waitt retired from the company in 2000, only to have to return after Weitzen and others screwed things up.)

But those cultural problems also reflected the fact that the computer industry was changing in ways that made it tougher to be a down-home company. New competitors, such as eMachines, had no qualms about outsourcing their components, driving down PC prices significantly and putting upmarket competitors in a lurch.

The rise of eMachines and similar firms negatively impacted players such as Packard Bell, but Gateway was likely more deeply impacted than most—and not just because the company struggled after they appeared on the market.

See, in 2004, Gateway bought eMachines. It was the classic example of a reverse takeover, highlighted by the fact that the eMachines’ CEO, Wayne Inouye, replaced Waitt as CEO—and immediately started replacing thousands of American jobs with outsourcing.

Amid the PC industry’s downturn in the early 2000s, Gateway started outsourcing to some degree basically to keep the bulk of the company afloat. But Inouye, a former Best Buy executive who had turned around eMachines, had no cultural ties to the old model, and the massive cuts he implemented underlined that point. Businessweek reported that the company had cut more than half of the firm’s 8,500 employees in roughly a year.

By the time Inouye left in 2006, the company had just 1,800 employees. The firm had a profit for the first time in years, as well as a place in traditional retail channels thanks to eMachines’ existing agreements, but it came at the cost of thousands of jobs.

A year and a half after Inouye left, the Taiwanese computer giant Acer bought the company for $710 million, and while the brand lives on today, the cow spots are basically the only signifier of what the firm once was.

Gateway’s record of outsourcing became a political liability for a former company president and CEO

While Ted Waitt probably saw the most financial success from his time with Gateway and remains a multibillionaire to this day, arguably the most well-known person associated with the company was Rick Snyder, a longtime board member who at various times served as Gateway’s president, chief operating officer, chairman, and interim CEO.

Snyder, while having a much smaller net worth than Waitt—smaller being relative, as $200 million is certainly not struggling—found later success in the political realm, serving as governor of Michigan for eight years and even coming up in Mitt Romney’s search for a vice president in 2012.

Romney, by the way, actually has a history with Gateway: He got the company to agree to a sponsorship deal to supply computers to the 2002 Salt Lake City Winter Olympics, which the current senator was brought in to organize. The deal with Gateway was last-minute, the result of having to ditch IBM, whose machines were used to disastrous effect at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta. Romney prominently featured this interaction in a book he wrote ahead of his 2008 presidential run.

But Snyder’s political rise highlights how the harsh economic realities that lead to outsourcing make for bad political optics. When Rick Snyder ran for office, he faced a ton of questions about his track record on outsourcing. One example of this comes from a conservative blog, Republican Michigander, which went to the trouble of actually checking the bottoms of old Gateway accessories to confirm that they weren’t actually made in the United States. (Weird flex, but OK.)

Blogger Dan Wholihan noted that, due to the loss of auto-industry jobs associated with the region, having an affiliation with outsourcing was political poison.

“This is Michigan. Our backbone is manufacturing, and for all this talk about diversifying the economy, all the talk of the cookie cutter new urbanism and creative class claptrap that Richard Florida types say is our future, we can not throw manufacturing under the bus,” Wholihan wrote. “Diversifying the economy must include manufacturing.”

Wholihan predicted that Snyder, if he won the primary, would lose the general election in a landslide. Instead, he served two full terms. Part of the reason for that is that Snyder got ahead of the issue and could make the case that he was a voice of opposition on Gateway’s board.

Snyder, a member of Gateway’s board throughout both its periods of success and struggle, stated that he disagreed with the moves to outsource, and noted that when he became interim CEO in 2006, he brought some of the outsourced jobs back. (This is true, but the company sold off to Acer soon after he left the CEO role.)

“I was a minority voice on the board, saying I didn’t agree with several of those steps,” he said, according to The Ann Arbor News.

Still, the outsourcing issue gave critics a quick way to dig at both Snyder’s business record and his gubernatorial record. Shri Thanedar, a Democrat who ran in the gubernatorial primary last year, pointed to Gateway’s outsourcing when offering his opinion on Snyder’s track record.

“He went to Gateway and managed the billion dollar corporation and he looked at jobs and Gateway outsourced jobs,” Thanedar said when announcing his run in 2017. “They were focused on the bottom line and that’s the kind of mindset he brought to Lansing.”

Snyder had other, more pressing, political crises on his watch—most notably the water crisis in Flint, which has made Snyder the subject of investigation in recent years—but the fact he even had to deal with Gateway’s outsourcing issues at all says a lot about how outsourcing is much less a business liability than a political one.

Analysts cheer on companies that cut the fat—but those are real people and real jobs, and job loss makes people mad.

The thing about Gateway is that the company got really lucky for a few years. It had an enviable hot streak at a time when marketing could make a big impact.

But when the going got tough, though, it turned to outsourcing, just like the rest of the tech industry, as a survival tactic. And while it happened with a trickle at first, when a leader with less commitment to the company’s original goals was installed, it eventually turned into a flood.

Whatever the underlying reasons, the fact of the matter is, Gateway felt it could not execute on its original mandate—computers so Middle American that they wore their affiliation directly on the box—while still keeping manufacturing and assembly inside of U.S. borders.

This is not a new story, and it’s not one limited to PCs. We can debate for weeks whether tariffs are an effective solution for helping to dissuade outsourcing—and ponder whether market disruptions like the one that destabilized Gateway would be prevented if more stringent tariffs had been in place in the early 2000s to discourage lowball competitors.

Likewise, we can debate whether cheaper computers enabled by loose trade regulations help the broader economy by making innovation accessible to more people.

But we should be bummed that a clever, innovative company that was built out of nothing on farmland couldn’t find a way to keep its values intact on the global market.