Image: VICE

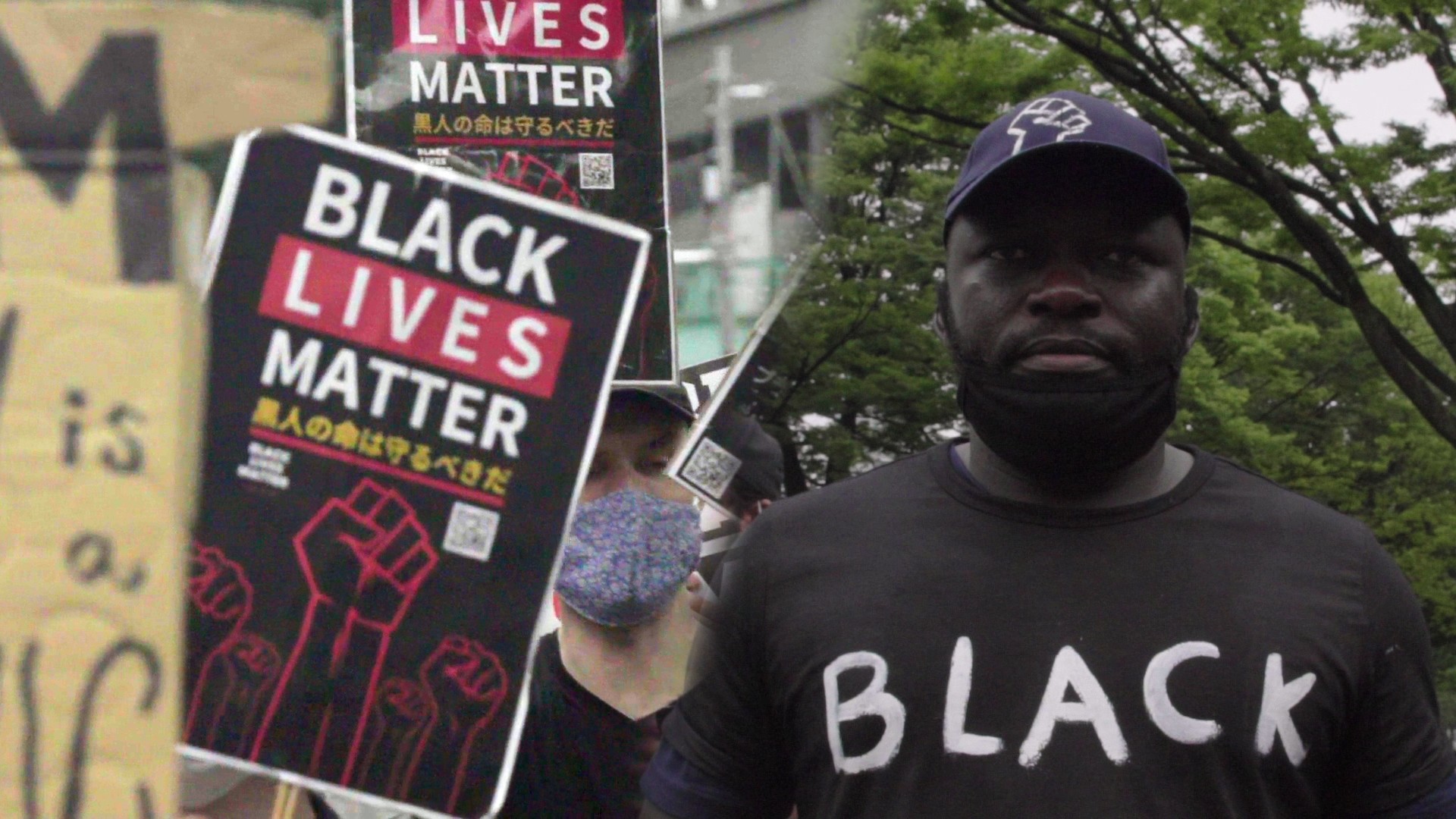

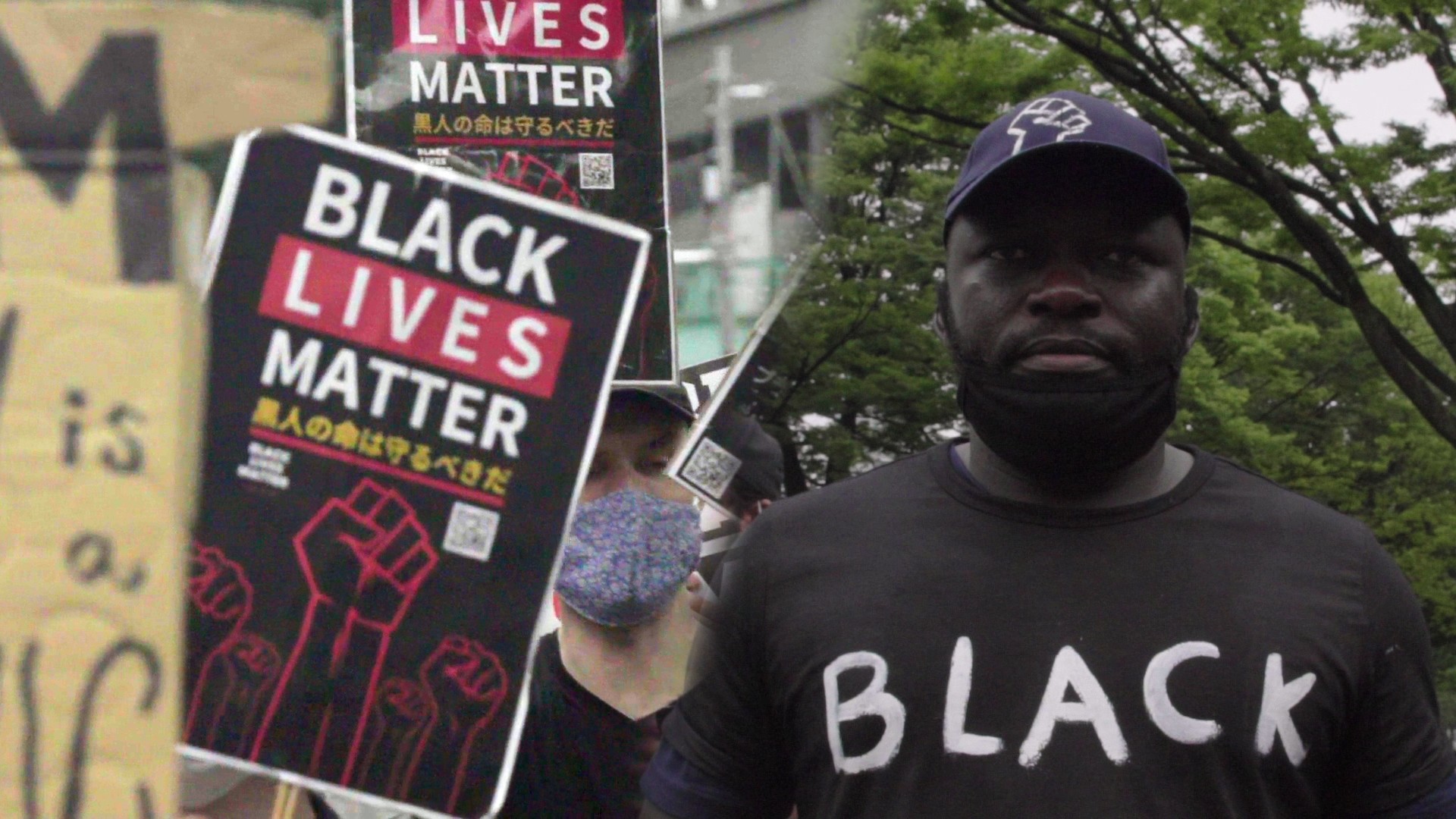

It’s long been obvious that the Black British community has a unique way of engaging with Twitter, whether it’s inventing new internet vocabulary or just its wacky sense of humour. “Black Twitter”, more generally, refers to the network of Black users who’ve cultivated an online community through shared interests, humour, and political concerns. While the term was first attributed to African-American users, there have been offshoots in countries with large Black diasporic communities, such as France or – in this case – the UK.The British corner of Black Twitter has been through a drastic transformation since the launch of the platform in 2006. As podcaster Victoria Sanusi recalls, “it used to be a space where people would [engage in] storytelling and go viral”, but now “it’s short verse”. It’s serious statements about Black Lives Matter, but it’s also memes and arguing about who has the best jollof rice.Over the last year, the community did not disappoint. During the pandemic and re-emergence of the BLM movement, we’ve not only had to process traumatic events internally, but also alter how we engage with others. Twitter offered a convenient platform for many Black people to stay connected, engage in topical discourse, have a massive laugh and find joy through pain.In this roundtable, some of the most popular users in the community talk about everything from the way Black Brits interacted on Twitter during the height of the pandemic, to their recollections of “black square” summer, to the infamous saga involving a baker selling monkeys online. Only on Black Twitter.Ava Vidal AKA @thetwerkinggirl: When I saw the COVID deaths [toll] coming through, it didn't feel real. What I did find interesting, as a Black person on Twitter, was how the attitude changed. So, I remember when it first started, there were a lot of Black people saying “we don't get COVID” and they were super confident about that. Then the numbers of Black people who were dying from COVID started coming in. I was trying to use the platform to say “look, you've got to stop saying this, people are dying!” We were trying to speak to aunties and uncles and basically say “stop it, garlic doesn't kill COVID!”Stefan Bertin AKA @stefanbertin: You use that platform to escape, but then that platform becomes really dark and draining. So, then what do you do?Victoria Sanusi AKA @victoriasanusi: You're going on [Twitter], you're seeing the death toll. Then you're seeing how the British government are handling it… and they're not doing well, they're being disrespectful. We're hearing all these things that are coming out from the government [about] what they're doing behind closed doors and it's making you feel “do you ever rate us? Like, is this a joke to you?”Paula Akpan AKA @paulaakpan: We were all just trying to make sense of this completely unprecedented situation. I think using Twitter actually made me more anxious towards the beginning of the pandemic, and I had to consciously step back from it a few times.Victoria Sanusi: There was definitely a time when I had to delete the app for a bit because it just felt like it was just too much to deal with and, at the same time, that coupled with [the murder of] George Floyd was just a lot. I was looking back the other day like “how was I on the internet last year?” It was just so much to be on the internet as a Black person.Kelechi Okafor AKA @kelechnekoff: I think that people were on [Twitter] a lot more [last summer] and I think that contributed, obviously, to the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement and certain topics that wouldn't usually have gained much traction.Vidal: Around [George Floyd’s] murder, [Twitter] was very sympathetic. It was very much white people in your inbox asking if they've ever hurt you…Then [the tweets] just got nasty again.Sanusi: I think at the time, I just felt so much rage from the George Floyd murder [and] the whole world “waking up” to what racism is? I think that just sparked a lot of rage. I saw a lot of people who were racist in the past wake up to be like “oh my God, if any Black people need help, blah, blah, blah” and I'm here like, “really?” So I think for a lot of [Black people] it was a time where it sparked a lot of rage in us… and rightly so.Zeze Millz AKA @ZezeMillz: With Instagram, people might post a picture and sometimes you don't really read the caption, you just see the picture. Whereas [on] Twitter, it’s obviously word-based, so there's a lot of different emotions going on [and] a lot of angry hurt people.Okafor: For Black people, Twitter hasn't always been escapism because should a Black person, especially young Black children, be killed at the hands of police or any sort of brutality, you'll find [their pictures] flying across your timeline. You came to laugh about Real Housewives of Atlanta and suddenly you're seeing a six-year-old [Black] girl being dragged by her hair out of her school because apparently, she “misbehaved”.Sanusi: I feel like sometimes you go on Twitter and it's like a game, like what's going to rage Black people today? What is going to make Black people annoyed? And I feel like sometimes for your own mental health you have to be like “I can't, not right now”.Okafor: Because there was this collective focus on calling out organisations and people that needed to do better, I think that a lot of people felt safer to be like “okay, this is the time that I need to do this”.Richie Brave AKA @RichieBrave: To see people finally understand the things that you've been saying has been a great comfort, and I feel like the minds of our community have been opened now. We can't go back to how we were before. I think it'd be unfair to label people [as] performative, but I feel like some [Black] people were grifting off the back of [BLM], and built platforms and built careers for themselves off of the back of Black pain that they were never interested in in the past. Okafor: We call French [Black] Twitter “Lupin Twitter” or “oui oui Twitter”, and they call us “Top Boy Twitter”. I just think that those things are hilarious because it's like that jest of siblings mocking each other.Sanusi: It makes me laugh when African-Americans cuss the way we talk and call us “cup of tea” lads [or] “innit Blacks”.Millz: I remember, specifically, when the African-Americans were trying fufu and pounded yam and Black British Twitter went for African-Americans because we felt they were being a little bit disrespectful. Then there was just this whole divide – sometimes it's like a sitcom.Okafor: I like the upbeat, kind-spirited diaspora wars that are jollof wars. We argue about who has the best jollof rice, and things like that, I just think all of that's fun. That's lovely. When [it comes to] conversations around the wounds that we have, that manifest differently based on the places that we find ourselves – that's when the diaspora wars kick in.Brave: I feel like Twitter has the potential to be a connecting force, and it has been, but I feel like the difficulty sometimes is we jump into these arguments, because maybe we've got a bit of hurt and tension and misunderstanding about other communities, and we just project it onto each other. And [we] see more of that with the lockdown and the pandemic and after Black Lives Matter. I feel like a lot of us are holding a lot of hurt and a lot of trauma and rather than processing that internally, and processing that together, what we do is we project it onto each other, and it moves us further apart.Ash X AKA @ashindestad: The past year’s probably been the funniest. We all use humour as a way of processing the bullshit going on outside. Monkey-gate definitely stands out for me.Sanusi: A guy tried to sell two exotic monkeys and it was just insane. The maddest thing was that apparently the same guy sells sprinkle cakes. It was just so hilarious… he said that the monkeys were going for £5,000 and this influencer innocently said that she spent £5,000 on herself for her birthday and people were like “did you buy the monkey?” [laughs] You can’t write that kind of stuff.Sanusi: I think it's actually become part of Black British culture.Okafor: The things that we thought would be the ostracising facet of the show [is the] saving grace, because [it allows Black people to] just watch white people mess and we're not deeply invested in it because there's no one really that looks like us.Sanusi: It's just escapism. And I think that's why a lot of us don't want Black women on that show because we know how we're treated in the dating world, so we don't want to relive that shit show.Mariam Musa AKA @missmariammusa: [Black people] rarely get featured on reality TV, and [when we have] it was always quite negative. So, we can sit back and watch. We can come together and just laugh about things. It allows us to see what dating is like for the white community.Okafor: I love the energy that [the show] brings to the timeline. Black people deserve happiness, Black people deserve things to be trivial. They deserve to just have that source of fun. Bertin: I definitely think it's a community that that exists.Musa: I think Twitter unifies us. We're all open to have a discussion [and] we all know what's going on. When is there really a place where you can spend loads of time with the same people, with the same culture and have the same banter? It just makes that site a happy place.Okafor: I think that while Twitter does allow for us to unify as Black people, it also does really amplify the things that we should be addressing that are the cause of division within the community: colourism, misogynoir, homophobia, transphobia, these are the things that we do need to address as a community.Akpan: I think that being on Twitter, and specifically being on Black Twitter, brings a lot of joy.Brave: Essentially, we're trendsetters. Let's be real. TikTok, Instagram, Twitter, all of it. The trends, the music, the dance… everything you see comes from us. It starts with us, whether people like that or not.Okafor: Social media has been able to thrive literally, because of Black people. The culture that Black people bring to the internet is what allows these platforms to be profitable and to be popular.Brave: I have seen a bit of clique-ness on there, and I don't think it matters about how many followers you have. I think it's about who your friends are, and who your friends aren’t. But I feel that we're starting to move past that a little bit.Millz: You kind of know who like the cool kids are on there or who everyone's going to like. I just feel as if everyone gets to be this version of themselves on Twitter that they know they could probably not be in the real world or face-to-face with somebody.Okafor: There are different groups of people existing in different areas and I think that’s also based on shared interests. So, if they're interested in economics, you get that economics group of Twitter, then you've got the techie group of Twitter, football Twitter, fashion girl Twitter, academic Twitter and then you've got what people call the “book deal” section of Twitter. You've got everyone kind of spaced out. But sometimes these things, like a Venn diagram, overlap. Sanusi: Banter.Vidal: Inspirational.Millz: Educational.Ash X: Hilarious.Musa: Unique.Okafor: Phenomenal.Akpan: Unmatched.Bertin: Hilarious.Brave: Dysfunctional… family.

Bertin: I definitely think it's a community that that exists.Musa: I think Twitter unifies us. We're all open to have a discussion [and] we all know what's going on. When is there really a place where you can spend loads of time with the same people, with the same culture and have the same banter? It just makes that site a happy place.Okafor: I think that while Twitter does allow for us to unify as Black people, it also does really amplify the things that we should be addressing that are the cause of division within the community: colourism, misogynoir, homophobia, transphobia, these are the things that we do need to address as a community.Akpan: I think that being on Twitter, and specifically being on Black Twitter, brings a lot of joy.Brave: Essentially, we're trendsetters. Let's be real. TikTok, Instagram, Twitter, all of it. The trends, the music, the dance… everything you see comes from us. It starts with us, whether people like that or not.Okafor: Social media has been able to thrive literally, because of Black people. The culture that Black people bring to the internet is what allows these platforms to be profitable and to be popular.Brave: I have seen a bit of clique-ness on there, and I don't think it matters about how many followers you have. I think it's about who your friends are, and who your friends aren’t. But I feel that we're starting to move past that a little bit.Millz: You kind of know who like the cool kids are on there or who everyone's going to like. I just feel as if everyone gets to be this version of themselves on Twitter that they know they could probably not be in the real world or face-to-face with somebody.Okafor: There are different groups of people existing in different areas and I think that’s also based on shared interests. So, if they're interested in economics, you get that economics group of Twitter, then you've got the techie group of Twitter, football Twitter, fashion girl Twitter, academic Twitter and then you've got what people call the “book deal” section of Twitter. You've got everyone kind of spaced out. But sometimes these things, like a Venn diagram, overlap. Sanusi: Banter.Vidal: Inspirational.Millz: Educational.Ash X: Hilarious.Musa: Unique.Okafor: Phenomenal.Akpan: Unmatched.Bertin: Hilarious.Brave: Dysfunctional… family.

Advertisement

The unprecedented year begins

Advertisement

Summer of black squares

Advertisement

Advertisement

From jollof wars to diaspora wars

Advertisement

Finding humour despite the trauma

Advertisement

Bertin: I remember last year, there was a meme calendar – every month, there would be a picture of which meme was big that month. It's almost like you can't do that anymore because there’s a new meme every couple of days.Sanusi: There're so many memes that have derived from Black Twitter. It's really become like a culture itself and it’s even entered [internet] vocabulary, like that tweet where it said “RIP aunty, the evil you’ve done in this world is enough”.Vidal: I like those moments where one of us has done something so god damn stupid. One moment you're really trying your best not to really say anything and the other you are just liking these wild tweets that are so so funny.

Millz: Even if it's just for you to release some sort of emotion or energy, Twitter is the place. Whether you want to be funny, or you want to be serious, that's where it all resides. I just feel like there're so many hidden comedians on Twitter.Sanusi: I just go to spaces where I feel like I can get my source of entertainment, I can get my sort of representation. That's why I follow people like Oloni. I think she's amazing. She's got such a great platform. She uses Twitter in such a way where she just commands the audience. She’ll be like “ladies let's have some fun” and we're gonna go over there. That's just jokes.

Advertisement

Okafor: What is fascinating about Black Twitter generally, but Black British Twitter specifically in this case, is what it showcases about resilience and how Black people across the diaspora have been able to survive this long at the mercy of white supremacist patriarchy. Humour definitely has to play a role in how you take something that is mundane, maybe traumatic in some cases, and reclaim your power within that by shifting how you interact with it.Akpan: When things get bad for Black people, Black people just get funnier. I think we are completely unmatched in our niche humour. There is just a certain je ne sais quoi. It's our way of speaking in code with one another when we're watching things like Love Island or dealing with the very traumatic and brutal realities of being a Black person in this country.

The popularity of ‘Love Island’

Advertisement

‘Black Twitter’ as a concept

Advertisement

The existence of cliques

Advertisement