A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

I’ve only dealt with the theft (or potential theft) of computers a handful of times in my life.

Videos by VICE

One of those times came about five years ago, when someone stole a laptop of mine, but was caught before the device was gone for good.

Perhaps I could have prevented its movement and near-theft had the device had a physical lock on the side. This locking capability, while perhaps not used by many home users, is actually fairly common on many modern computers, particularly of the laptop variety. The device that was nearly stolen had it!

Clearly had I thought ahead, I could have stopped it from being pulled away—at least that’s the theory. The truth about the Kensington security slot, the predominant security device found on portable computers, is a little more complicated than that.

1984

The year IBM first released the Personal Computer AT, a device that featured a physical lock on the front. The high-end machine, which sold for more than $4,000 in 1980s money, used the lock not to prevent the machine from being picked up and taken away (its large size helped on that front) but to prevent the machine’s keyboard from being used when the primary user was away. It was effectively a physical version of a password. As How-To Geek notes, this feature became a key element of many PC clones through the early ’90s, though, like the Turbo button, it eventually faded away as cost-cutting won the day.

The company behind the Kensington security slot is also behind a lot of other things

A paper clip would make a terrible lock. Made of a thin material, paper clips can be easily bent out of shape and rejiggered any which way but Tuesday. And most people could bend it with their bare hands, no special lockpicking tools needed.

But a company that became famous for turning a paper clip company into a stationery conglomerate is largely responsible for the rise of the Kensington security slot in the modern day.

Founded in 1903, the American Clip Company became an office and stationery supply giant initially off the back of the paper clip. It eventually evolved into ACCO Brands, a firm responsible for many innovations in the office and classrooms you take for granted—and some you’re probably not even aware of. A few of ACCO’s well-known brands:

- Mead. This well-known maker of stationary materials, most famously the Trapper Keeper, sold most of its office-supply offerings to ACCO Brands in 2012.

- Five Star. This maker of school supplies, at one point a Mead product line, has evolved into a brand of its own, and is the one you’ll likely run into if you’ve needed a giant binder of some kind in the last decade.

- Advanced Gravis. This now-defunct company, acquired in 1997, was famous for creating game controllers targeted at PC users—most famously its Gravis Gamepad, a necessary element of any worthwhile Commander Keen session. (PowerA, a gaming accessories company, carries the torch for ACCO today.)

- Swingline. A famous maker of staplers, the company’s best known stapler—a bright red one featured in the movie Office Space—was not actually something the company offered at the time of the film’s release, but eventually became a big seller once they resolved that.

And that brings us to Kensington. Started in 1981 as Kensington Microware, the company found its footing making accessories for the IBM PC and Apple II, largely surge protectors and input devices. An early hit for the company was the TurboMouse, an early trackball device for the Macintosh that dates to the late 1980s. As Anil Dash will tell you, Prince was known to use Kensington trackballs.

In many ways, Kensington, which ACCO acquired in the late 1990s, has become the key umbrella brand for ACCO’s digital efforts. To this day, the company has interests in trackballs, but it’s expanded its product base into docking stations, laptop bags, standing desks, mouse pads, travel adapters, and (of course!) device security.

Around the late 1980s and early 1990s, the market for computer notebooks was growing in earnest, and concerns about security were growing. Kensington, a firm with an interest in computer accessories in all forms, was early to the endeavor, selling the endeavor initially as the MicroSaver, a brand name that dates as far back as 1984 (though not in its later context as a locking mechanism).

And as laptops became more common, physical security elements were directly baked into them. A 1992 article in PC Magazine described the benefit of this strategy as helping to sell the concept of laptops to businesses, which clearly might have misgivings about allowing machines that cost thousands of dollars to leave the building on a daily basis. In that sense, the security slot was an effective way to ease the concerns of early ’90s IT departments.

“When the lock is closed, the notebook is secured to the desk,” author Christopher Burr wrote. “If someone tries to steal it, they’ll either be discouraged or they’ll destroy the notebook case in the process, making it practically worthless.”

At the time, laptop manufacturers’ support of this endeavor was seen as essential to making this possible, and Burr wrote that major laptop makers of the time, such as Toshiba and Compaq, were working to support locks such as Kensington’s.

While there have been some changes over the years, the Kensington slot survived on many Apple laptops through to the unibody MacBook Pro, which was sold until 2016; many modern Windows PCs and Chromebooks still have it, and for devices that don’t have one, like iPads, the company has been known to create custom proprietary designs to secure them.

There’s just one problem, and it’s on YouTube.

“Many of the locks are now nothing more than expensive scrap metal and many bicycle owners are in jeopardy of having their bikes easily stolen.”

— Sean Dewart, a biking enthusiast and a plaintiff in a 2004 lawsuit against the bike lock maker Kryptonite, speaking out against the weaknesses of the well-known lock variant, which used a tubular pin tumbler lock that was notably defeated through the use of a ballpoint pen of the kind Bic makes in the billions each year. Kryptonite was forced to start an exchange of its locks as a result of this incident, and changed the design to something that could not be taken out by a standard pen.

A lock-developer responsible for many of Kensington’s lock patents is frustrated with the state of lock security

I tried to reach out to Kensington multiple times through multiple avenues to write a nice feel-good piece about an object so common on modern computers that many tech reviewers don’t even bother to mention it if it’s there, but the company didn’t respond.

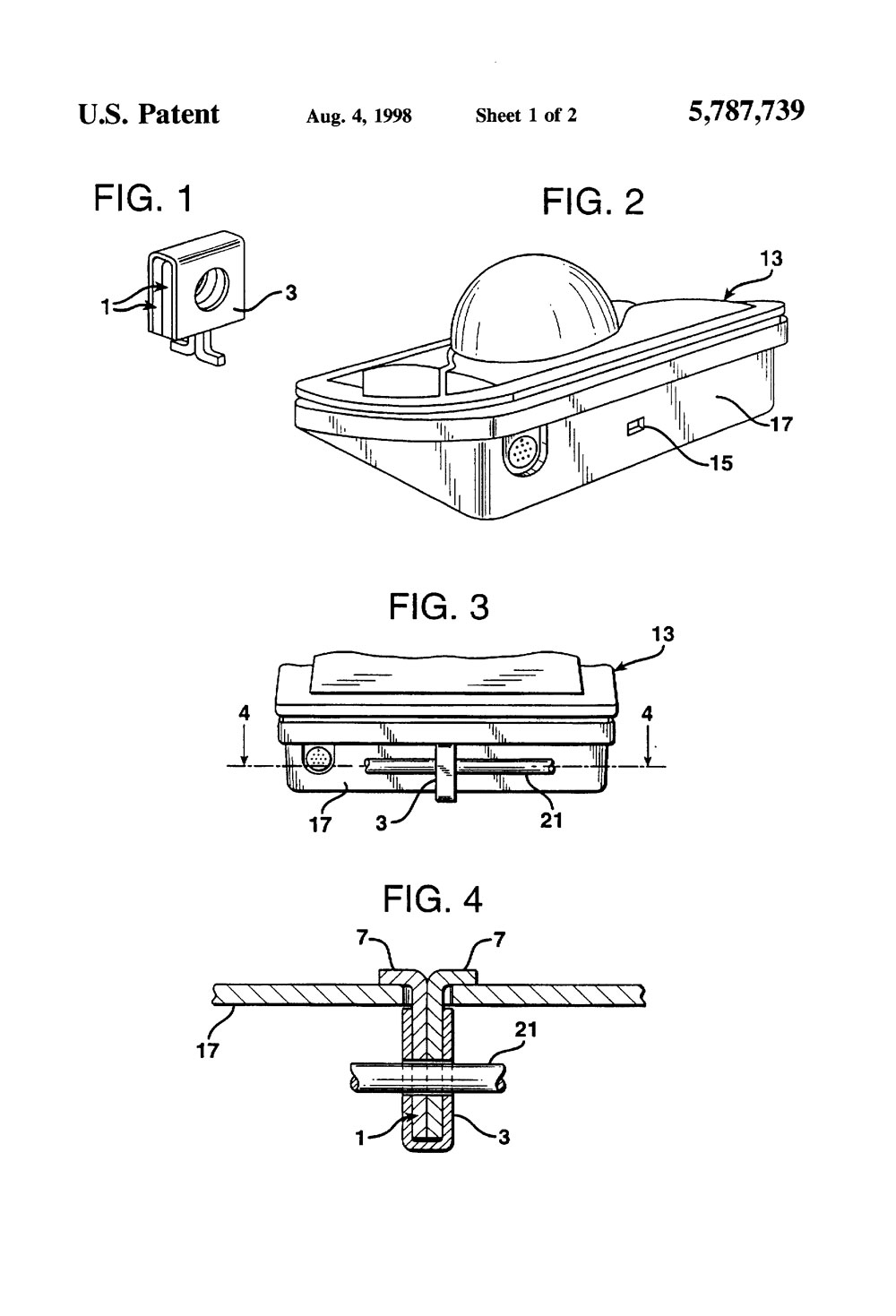

So I tried another avenue, and got decidedly different results. I dug into Google Patents and looked around and saw who had helped to patent the devices that had come to define physical computer security over the years. One name in particular kept popping up, and he had both a website (a number of websites, actually) as well as a Twitter account with an avatar featuring a Kensington security slot (32 followers as of this writing, including me).

And honestly, I kind of got the impression that the person was still smarting from the existence of the LockPickingLawyer.

If you watch a lot of YouTube, you most assuredly know the channel, which has more than 3 million subscribers; it’s a channel where an unnamed man of a presumably legal background takes every single type of lock known to man and dismantles them in short order.

Locks of the kind that fit into the Kensington security slots are not immune from the interests of the Maryland-based lawyer—and in fact, when said LockPickingLawyer took his talents to a Kensington laptop lock in 2019, the effect was downright embarrassing for Kensington.

For one thing, the LockPickingLawyer noted that he didn’t actually need to pick the lock to remove the device, because of the thinness of the cable it was attached to. With the right cutting tool, he said, a person could break through. But then he proceeded to pick the lock anyway with a basic tool, one that dismantled the device in mere seconds.

The comments implied that the lock was more posture than security, though he wasn’t the first to point this out. In 2007, an early YouTube video with horrible acting pointed out that, not unlike the Kryptonite locks that faced a recall in the mid-2000s, the Kensington locks could easily be defeated with just a piece of rolled-up cardboard. Designs have admittedly changed over time, but point taken.

For years, Jay S. Derman played a key role in developing locks just like these, used in offices, kiosks, and retail locations the world over. Derman, an inventor of locks and other security-related equipment, has been developing different kinds of physical security mechanisms for nearly 50 years, first starting in the mid-1970s during the fuel crisis.

“Rather than waiting in line and not wanting my gasoline stolen when it was $1 a gallon, I made a locking gas cap,” he recalled in a phone call with me. These gas cap locks ended up becoming a viable side business for him and eventually turned lock-making into his full-time job. (Side note: passionate guy; he did most of the talking.)

Eventually, as gas cap security became less of a consumer need, he began building security mechanisms for electronics, with his first couple of patents reflecting the security needs of their time—car stereos (whose myriad security issues we’ve discussed previously) and VCRs (as a really ambitious parental lock of sorts). After he found success building those, he moved into slot-locking mechanisms for floppy disk drives.

Those early patents actually explain how Derman became associated with Kensington. Long story short, the company violated his patents by creating slot-based locking mechanisms that were very similar to his—leading him to file litigation against them in the mid-90s. But the lawsuit actually turned into the start of a business relationship when Kensington and ACCO Brands acquired his early patents and kept him on as a designer for hire, a regular gig that was quite lucrative for him when he was doing it, receiving payment in the five-figure range for some of his inventions, which he produced regularly, and only some of which he patented.

“On some of the prototypes, they paid me money for it; some they didn’t care for,” he said, adding that not everything was turned into a patent, but he kept inventing at a regular clip. “I would make one a week, then. I know that seems like a lot, but it’s true.”

Derman’s work with ACCO and Kensington led to numerous patents over a period stretching out longer than a decade, though he says the collaboration ended around 2010 or so, as the company decided to bring its development work in-house.

It was a good run, but Derman didn’t strike me as a particularly nostalgic guy who focused on his prior victories; most of our call, in fact, barely even focused on the Kensington security slot. Instead, he was really focused on the state of modern physical security—or lack thereof.

2006

The year that Kensington won a patent-infringement lawsuit against another major accessories manufacturer, Belkin, over the design of its security locks. “We created the security slot found on 95 percent of all laptops made today and have made substantial investments in patented locking technologies that benefit consumers,” Kensington’s then-president, Boris Elisman, said. “We intend to vigorously defend our intellectual property rights and protect our patented products.”

Why the guy who helped develop many of Kensington’s locks wants to beat the LockPickingLawyer with his latest lock design

Throughout our call, Derman seemed determined not to dwell on his past successes alone. Much the opposite, in fact. When I tried to lean on the nostalgia angle or the sheer reach of some of his inventions—a bit of a softball that I naturally ask in cases like these—he wasn’t having it.

“My slot lock? Well, it’s not helping them anymore,” he says, explaining that physical locks must adapt with the time just as digital security often does. “If someone wants to steal it, they can steal it. Because there’s someone on the computer or on the cell phone, they can learn how to steal it, if that’s what they want.”

When I pressed him on whether he felt any warm feelings about his past work, I got the impression that, instead, he was concerned instead about the many locks out there that weren’t actually secure, because of the growing interest in videos that reveal the secrets of locks we use every day.

Perhaps for this reason, Derman—who has moonlighted in developing things such as soap dispensers that work with regular drinking glasses and mouse traps that improve on a basic design that is more than a century old—has started to pick up interest in coming up with new types of locks once again. In 2019, he filed for a patent for a lock with a design that he hopes will prevent the LockPickingLawyer (or anyone else, for that matter) from breaking in; he was granted the patent back in May.

The design is built around a standard padlock-style design, but wraps an additional metal chamber around the outside of it, so the lock itself can only be accessed with an extra-long key. He notes that any padlock can be pressed to its limits, but at least his design should prove a serious challenge to anyone hoping to break into it using traditional lock-picking methods.

“If they can’t get in using the padlock and they want to rip the door down, okay, that’s not taking the lock. But they did have to go through an extra effort—but big time extra effort and a lot of noise—to rip a garage or a storage door open or a gate open, you know, break it down. But that’s not kicking it in: That’s using an electric drill, or using a hydraulic cutting tool, or a portable electric saw.”

In many ways, Derman took the underlying point of the LockPickingLawyer’s many videos to heart: Many physical locks—including those sold by large, mainstream brands—represent theater, not security. So he used that knowledge to build a better lock that may be strong enough to represent security, not theater.

He has yet to sell the lock design to anyone (he’s taking offers now), nor has he been able to convince the LockPickingLawyer to take a stab at his patented device, but one hopes it eventually happens.

Having talked to Jay, I can say that he is truly someone who took that YouTuber’s point to heart.

My experience talking to Jay Derman had me thinking a lot differently about the Kensington security slot than I first did when I first decided to look into it.

I think, certainly, that physical security is a real concern for many companies and the ability to secure a device to a specific location matters in areas such as retail and public-facing kiosks. And even if being able to attach a slot lock to the side of your laptop makes you feel better about keeping your device safe, as a Kensington lock does, it may not always be that way in the future.

Maybe Derman is right. It’s hard to see the nostalgia in something that is more likely than ever to be defeated because of a bunch of videos on the internet that explain all their secrets.

The term “arms race” came up in our discussion at one point—implying that there will be changes to how we lock objects in the years to come as tactics shift and modern devices turn old hat. Compare it to, say, the use of SMS for two-factor authentication. At first, it seemed like a good idea, but then information began to spread that it could actually be broken, and now it’s seen as a bad practice.

To some degree, that’s what physical locks feel like right now. Granted, I don’t think people are necessarily picking every lock they see in front of them, and there is something to be said about the role of a strong security posture. Maybe when my laptop was stolen way back when, posture would have been enough to secure it for a short amount of time. But posture alone is not enough to keep your valuables safe in the long run.

I think the complexities of securing digital devices, where once-secure methods of protecting users bend and possibly break over time, will also eventually apply to many physical devices as well. You’re already seeing this with biometric padlocks and other types of locks that combine the physical and the digital. The problem is that, with the right information, even the best physical lock is fallible, even with a digital front door. That’s what folks like the LockPickingLawyer exist to underline.