When screenwriter/director Jessica Bendinger of Bring It On fame sat down to write Stick It, she had a simple yet provocative idea: what if you dropped a teenage rebel into the most tyrannical, restrained sport in the world?

The character that Bendinger came up with was Haley Graham, a former world-class gymnast who bailed on Team USA in the middle of the world championships, leading to a defeat at the competition. After a judge (the criminal court kind, not the gymnastics type) later sentences the property destroying ex-gymnast to hardcore gymnastics training rather than military school, Haley is perfectly positioned to inflict maximum chaos, and ultimately achieve both redemption for herself and the sport.

Videos by VICE

The film received some good reviews—including one from the New York Times—though most of the critical reception was decidedly lukewarm. But in the years since its premiere in 2006 a long 15 years ago, the movie has become a cult favorite and one of its more memorable lines—“It’s not called gym-nice-tics”—has become something of an unofficial tagline for the sport.

“Stick It is the only good gymnastics movie. It’s the only one that attempts to portray gymnastics correctly,” Kino, co-host of Half In, Half Out, an LGBTQ gymnastics podcast, said during a recent episode. (Morgan Hurd, the 2017 world all-around champion who was a guest during the conversation, seemed to strongly concur.)

Part of this “correct” portrayal that Kino is referring to is that the film features actual elite gymnastics in a movie about…elite gymnastics. The norm, both before and after Stick It, was to show a character doing low level skills, such as a back layout full, and then claim that the athlete was Olympic bound.

Fifteen years on from its release, Stick It remains the best movie made about the sport, which could sound like faint praise, given the quality of most of the pop-culture products created about gymnastics, but it isn’t meant that way. Stick It respected the sport enough to get most of the details right and used that earned credibility to critique gymnastics, which more than deserved the criticism. VICE spoke to the creators and stars of the movie to figure out what exactly Stick It did right—and how it did it.

Bendinger’s interest in gymnastics was not purely academic. She had spent her early years as a gymnast, training in the late 70s at Grossfeld’s, the famous—or depending who you ask, infamous—gym in Connecticut that produced the American women’s first world gymnastics champion, Marcia Frederick. (In 2018, Frederick came forward and said that Richard Carlson, one of the coach’s at Grossfeld’s, had sexually abused her.)

Jessica Bendinger, writer/director: I went there from fourth grade through sixth or seventh grade. And then I grew six inches in one summer. I lost my center of gravity. I was hitting my head. I just started chickening out and I knew it. I just didn’t have it anymore. They held me back to level three after I’d been third in the state on floor. It was a reality check. So I stopped. And then I was forever trauma bonded with gymnastics because I had so wanted it and loved it.

One of the people to read an early draft of Stick It was TV writer/showrunner Liz Tigelaar, who is an avid gymnastics fan and collector of gymnastics footage. (Some of the footage in the movie’s sizzle reel was pulled from Tigelaar’s vast tape collection.) Tigelaar introduced Bendinger to two former UCLA gymnasts—Heidi Moneymaker and Lena Degteva.

Tigelaar: Heidi and Lena are two of my closest friends, who I met because I was a UCLA gymnastics fan. I used to go to all the meets and loved both of them as a fan. Before Heidi became a stunt woman, she had a personal training business, and even though I was broke and couldn’t afford a personal trainer, I decided to just call on a whim to meet with her. I called and thought she’d have an assistant who’d pick up and she just answered her phone. We met, I loved her, of course, and I signed up for two sessions a week. Then later, we were doing a Breast Cancer Walk together and Lena was there. We had both been hearing about each other forever, so we met and became close, too. We basically all spent our twenties running around LA, figuring out our lives and careers together. I just adore them both.

Bendinger: Lena and Heidi and Liz came over. And I just picked their brains about, you know, injuries. And they helped me really get in the weeds.

Once Bendinger had a strong draft in hand, the process very quickly kicked into high gear with the project being picked up on a “progress to production” by Disney. Stick It marked her feature directorial debut.

To cast the film, Bendinger and the casting team cast a wide net, looking at both gymnasts and actors to play the main gymnast roles. Ultimately, the most significant gymnast roles went to actors who had no background in the sport, unlike in 2000’s Center Stage, which featured rising stars of the American Ballet Theater for the main parts. In order to ensure that the actresses without gymnastics experience would be able to plausibly play gymnastics, they had to go through a physical audition in addition to an acting one.

Bendinger: I was sick at home and I was watching TV and this young woman came on screen. And I sat up. I just sat up and I was like, Oh my God, that’s Haley. That’s the energy for Haley. I told Marcia [Ross], the casting director, please bring her in.

Missy Peregrym (Haley Graham): I hadn’t been working for a really long time at this point. I’d just done television and I was on a series Life As We Know It. I was repped by UTA at the time and I had received the script…but it was not from my agency. I was so confused, like how did we get the script?

I loved it. I loved the character of Haley. I wanted to go out for it and [the studio] just said no because I was too green.

Bendinger: I didn’t hear anything. I said, ‘Where’s Missy? Have we seen her yet?’ and [Marcia Ross] goes, ‘She came in. She wasn’t very good.’ I was like, ‘I don’t care. Bring her in.’

Peregrym: She kept fighting for me behind the scenes and I was able to fly to LA.

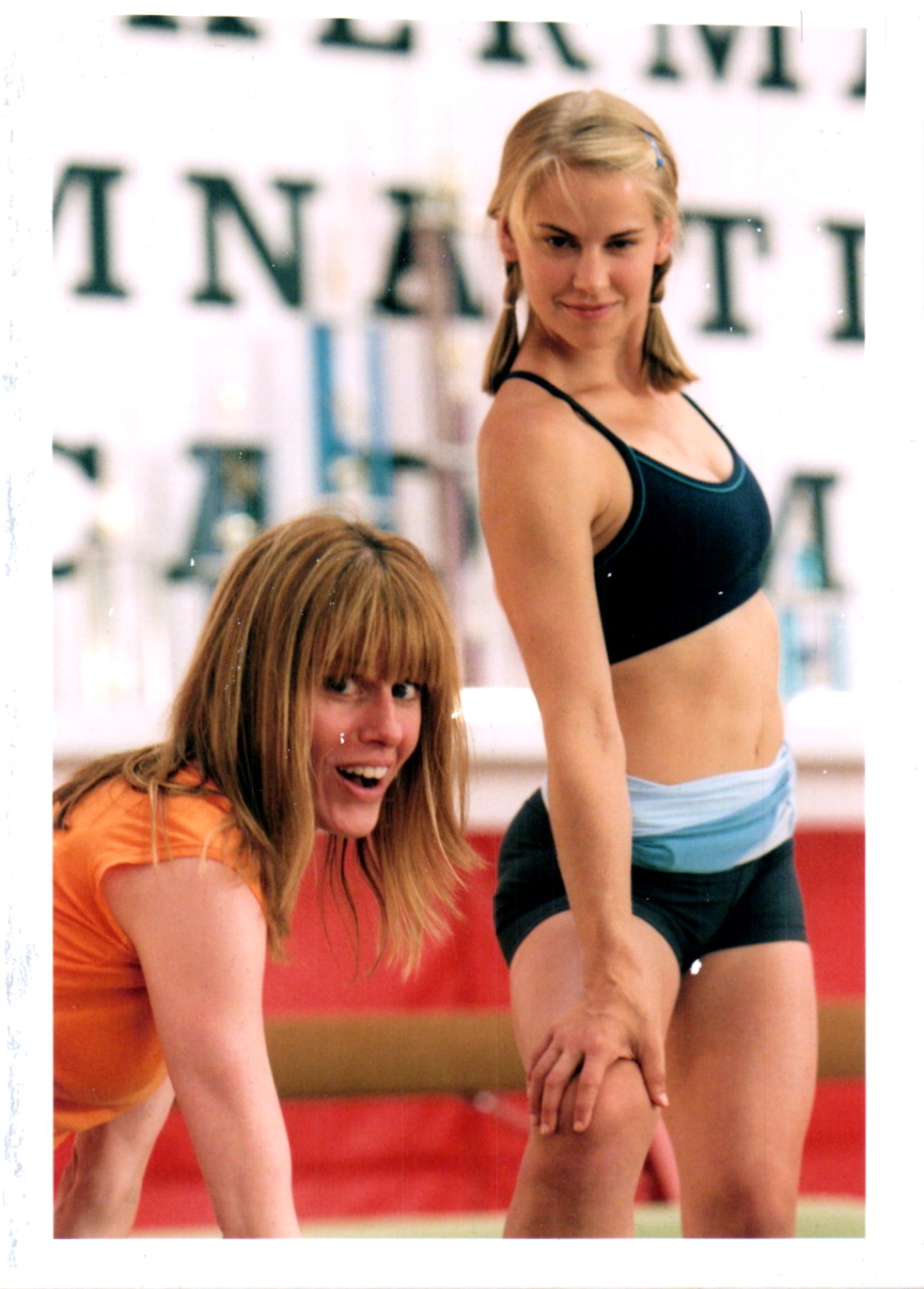

Tigelaar, who had worked on American Dreams, suggested one of the show’s actresses, Vanessa Lengies for the role of Joanne Charis, Haley’s foil at the Vickerman Gymnastics Academy.

Vanessa Lengies (Joanne Charis): First, it was an acting audition where we just got the lines and you just went in and read with a reader for a casting director. They loved that and said, the next audition there will also be a physical component to the audition where we’re going to test, not your skills in gymnastics, but your physical abilities to see if you can even portray somebody who might look like they know how to do gymnastics. I think it was two weeks between my first audition and my second audition. I looked up the local gymnastics training facility near me in Marina Del Rey and I went there and asked them if for two weeks, I could come in every day, and somebody could just try to train me as much as they can to look like I know what I’m doing.

The second audition, [they asked us], how many crunches can you do and how many pull ups can you do? Can you run? Let’s watch you run. They filmed the whole [thing]. I had bought this really uptight tracksuit, kind of like the ones that we wear at the end of [the movie]. I was so proud of this tracksuit because it just instantly made me feel pretentious. But I’m 5’1”/5’2” on a good day and this tracksuit was made for all sizes of women. You’re supposed to hem the tracksuit. I didn’t know that. When I did the audition part where we were supposed to run as fast as we could across the floor, I was halfway there and the tracksuit just caught my foot and I was eating that mat so hard. Everyone was there on that day because we’re in a gym. So it’s not like in an audition where you go in and the next girl is in the waiting room. All of the girls at that audition were watching. It was a screeching halt moment and then I just got up and I pretended as if I stuck the landing.

Peregrym: The scariest part was they made me do a dance routine and I’m not a dancer. I remember getting my sister to teach me. She came up with a whole routine for me to do, which I’m pretty sure I screwed up halfway through my audition. I had no idea what moves were coming out of me because I completely lost track of what I was doing. It was an out of body experience.

The physical audition was somewhat less daunting for Nikki SooHoo, who was cast as Wei Wei Yong, because the actress studied dance at an arts school.

Nikki SooHoo (Wei Wei Yong): I was like, I think I can swing this floor routine because I know how to dance and I had done gymnastics for dance so I could do an aerial. I could do a back handspring or a front handspring. I was like, ‘Oh, let me just work those things in and maybe it will be good enough.’ I remember them taking me to the bars and then asking me to do a pull up. That was like, no way. I could barely hang on those things.

In the original script, my character was really good at bars. They ended up changing my character to be good at beam because I was really flexible.

The only person cast in a major role that had any kind of gymnastics background was Maddy Curley, a former elite gymnast who had recently graduated from the University of North Carolina where she competed on their gymnastics team.

Maddy Curley (Mina Hoyt): I had majored in drama but then I went onto Teach for America right after I graduated. One of my friends was working at this casting agency in D.C. and was like, ‘Are you still acting?’ I was like, ‘Yes.’ She’s like, ‘You should come audition for this gymnastics movie.’ So I got a substitute teacher and drove up to Washington, D.C. and auditioned, and then got called back and then called a third time. Then they called about flying me out to Los Angeles to audition.

Then I didn’t hear anything for two and a half months. Then I started training at my old college. I had [been out of gymnastics] like seven months, maybe eight, but that feels like forever in the gymnastics world. I had gained 15 pounds so I had to lose 15 pounds. I would send pictures to show how I got my abs back and looked like a gymnast again, rather than like a retired gymnast.

Donagene Jones, gymnastics coach and choreographer: Maddy and I kept in touch. Not that I knew her prior, but she was so motivated to get the part. I was like, ‘You need to keep sending them videos. You need to keep sending them information that you’re getting fit and you absolutely want this part more than anything in the world.’

I saw Isabelle’s body and was like, I’m fucked. How am I supposed to look like that? She was the strongest person I’d ever seen.

Curley: I would teach a normal 8 to 3 and then I would drive to my old college about 40 minutes away, and I would train with the girls there with my old gymnastics coach, and then drive back home and grade all the papers.

I got a call from Jessica and she’s like ‘You got it.’ And she kind of jokingly said, ‘Please don’t ever email me again.’ I had written her so many times.

When Bendinger called Peregrym to let her know that she had gotten the role of Haley, it wasn’t a moment of unalloyed joy the way that it was for Curley.

Peregrym: I was outside in the alley at the vet, having just the worst day. My puppy was hit by a van. I had to leave for a second to take the call and Jessica tells me that I got the movie and I was just beside myself, like what’s happening in my life right now? Just the fullest experience of the best news and the worst news at the same time.

Whereas virtual unknown actors were being auditioned for the roles of the gymnasts and Haley’s male friends—Frank was played by a pre-Twilight Kellan Lutz—the male actors who offered the role of Burt Vickerman, the aging, somewhat domineering gymnastics coach who takes Haley under his wing, were decidedly A-list. The script for Stick It was sent to John Travolta and Kevin Costner, both of whom passed.

Bendinger: [Producer] Gail [Lyon] very wisely said to me, ‘Look, let them go through their list. Don’t freak out.’

I was freaking out so I did what all people in Hollywood do when they freak out—I called a psychic. I called a psychic that I love named Jo Madrid, who’s still around to this day. She had been very accurate about something weird that happened in my life. Don’t get me wrong; I make my own life choices, but every now and then I just want somebody to stick their finger in the wind of the unseen. So I told Jo, ‘I sold this movie. I need somebody to play lead.’ And she goes, hang on, ‘Bridges, the good looking one.’ And I go ‘Jeff Bridges?’ And she goes, ‘Yeah, the Bridges brother, the good looking one.’

So I wrote him this letter in script form about doing the script and [then] I heard Jeff will do a call with you. So we did a call. That was like an hour. And then it’s like, ‘Jeff needs to meet with you.’ I drove to Santa Barbara and met with Jeff. I think it was like a three hour meeting at the Biltmore in Santa Barbara. And Diana Ross, by the way, was having a meeting across the room, and so as I’m leaving. She’s like, ‘Jeff, Jeff!’ I’m like, ‘Oh my God, what is happening in my life right now? I’m with Jeff Bridges and Diana Ross.’ They offered him [the role]. It was his biggest offer [to date], $3.25 million.

It was like getting a Lamborghini when you just barely have your driver’s permit.

[VICE reached out to Bridges, who is currently undergoing treatment for lymphoma, via his representative, but didn’t receive a response.]

You can’t have a gymnastics movie without gymnasts. Bendinger turned to Paul Ziert to help him find the gymnastics talent for the film. Ziert used to be the head coach of the University of Oklahoma’s men’s gymnastics team where he trained Bart Conner to his Olympic triumph in 1984. He’s currently the publisher of International Gymnast Magazine.

Paul Ziert: I said [to Bendinger], ‘The gymnastics has to be authentic. And it has to be high level.’

Bendinger and Ziert were determined that the gymnastics showcased in the film would actually be world class, the kind that you might plausibly see in elite competition. This meant finding gymnasts who were either still competing or had only recently retired who could work as stunt doubles for the actresses and as the extras.

Ziert: I thought this would be easy, because there’s so many college gymnasts that are in still good shape. I was sure that they’d love to do this. Well, it turns out that because it was a Disney supported film, they required everybody on set to get paid so you couldn’t come on free. We had a huge list of college level, elite gymnasts who are willing to do the movie for nothing, just to be a part of it. But they were suddenly ruled out because it would have eliminated their [NCAA] eligibility. [The elite gymnasts likely had the same concerns re: eligibility because many, if not all, planned to compete for NCAA teams after their elite careers were over.]

I told [Bendinger], we have to go out around the world. I nudged my old friends to see who they could bring. I was a very good friend of Peggy Liddick [beam coach of 1996 Olympic gold medalist Shannon Miller and then the head of Australia women’s gymnastics program]. She sent us four girls from Australia, which helped a lot.

Ziert also reached out to the head of the Spanish women’s team, Jesus Carballo.

Ziert: He had two girls who were really, really good. We needed him to shoot stuff and he [would’ve had] to depart on a Sunday, which was supposed to be the finals of the Spanish national championships. He literally changed the start time and did it as an earlier competition. They finished up, ran to the airport, and flew to LA for the shoot. We got a lot of wonderful cooperation like that.

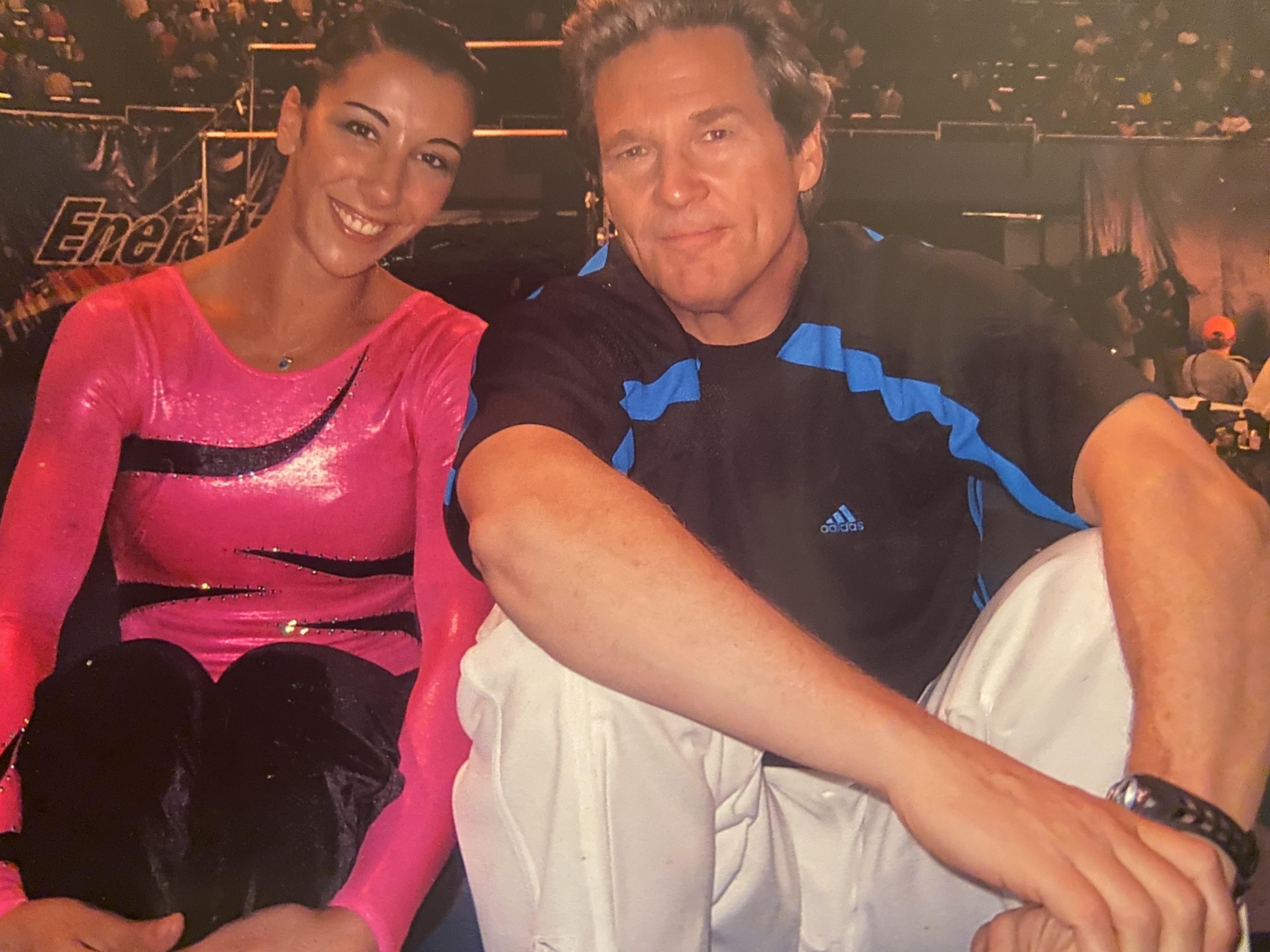

It wasn’t just a matter of finding high-level gymnasts who could be compensated; they also needed to find gymnasts who could physically match the actresses, at least in appearance from the neck down. But casting Peregrym, who is 5’6”, made finding an elite-level gymnast who could double for her particularly challenging. One of the only plausible options was Isabelle Severino, an elite gymnast from France who won the bronze medal on the uneven bars at the 1996 world championships. At approximately 5’7”, Severino was unusually tall for a gymnast. At the time that Stick It was in production, Severino was in her mid 20s and in the second phase of her elite career; she had retired in 1998 and performed with Cirque du Soleil before resuming training to make the 2004 French Olympic team.

Ziert: I had known Isabelle Severino for years and years and I was able to talk her into doing it.

Isabelle Severino: They asked me because they wanted a tall woman. In gymnastics, there are not many tall women with a good level [of gymnastics]. I came to LA to audition and I met Missy Peregrym for the first time.

Peregrym: I saw Isabelle’s body and was like, I’m fucked. How am I supposed to look like that? She was the strongest person I’d ever seen. I just couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t believe her ability. I was so scared that if I didn’t look like her, the whole movie was going to be terrible that it was not going to be believable at all.

That’s where the intense training regimen came in. Ziert recommended gymnastics coaches Pat Warren and her daughter, Donagene Jones, to train the actresses, the stunt doubles, and the extras during pre-production and filming. (Warren and Jones also assisted in the casting process.)

The actresses primarily trained at All Olympia Gymnastics Center (AOGC) in Hawthorne, California. The gym, which was owned by Artur Akopyan and Galina Marinova, produced 2010 world silver medalist Mattie Larson and 2012 Olympic champion McKayla Maroney. That location has since closed—though there’s another in Calabasas—after former gymnasts like Larson, a Larry Nassar survivor, sued the gym and the coaches, alleging that coaches engaged in abusive coaching practices.

Jones: We just started with Missy and Vanessa first and just gave them every insight into what a gymnast does, from putting on our grips to finding their mark on the vault runway to just how you would act in the gym.

Lengies: We did five days a week and probably six hours of training. The gymnasts who were in Level 10 gymnastics at [AOGC], 11 or 12 years old, they did six days a week of training. And on their seventh day, they still had to do cardio and stretching.

This is the first and only time that I went through such intense training. I literally lived on Aleve.

Peregrym: I would see these seven year olds in the gym who could just kick my ass in any of these things. I’m watching them just in awe of their discipline, of their ability, of the bravery to do what they’re doing. After watching them, training alongside these kids, and then going to a competition and seeing them at such a young age deal with that intensity, I still don’t know how I feel about it.

Pat Warren, gymnastics coach: Those kids were so wonderful to work with but they were so blown away with the conditioning that we had to do. We did an hour conditioning a day. I said, ‘Girls, you’re not going to look like gymnasts, you’re not going to get through this mess if we don’t condition.’

For arms, we did chin pullovers on bars, like when you pick yourself up [as in a chin up] and then you pull [your hips up and] over. Handstand presses. Well, they couldn’t do a press. So we had them put their hands down, stand on their feet, jump to a handstand and then try to come back down again to a [seated] straddle. That was a killer, trying to get them to do fricking leg lifts [hanging from a wooden bar against the wall]. We had to spot them. We said, ‘Just pull your legs at least to horizontal.’

Jones: [The] on the bar stuff was really hard, like where you’re hanging and you’re doing toe to the bar and legs lifts, yeah, body extenders, where you’re in a pike position you’re lifting, we had to spot them through so much. We’d make them hold handstands for at least like we got them up to a minute for sure.

Lengies: Dona and Pat had the monumental challenge of taking grown women and teaching a person who has never done gymnastics how to look like they might do gymnastics. They did not have an easy job.

I was most proud that by the end I could do like 100 leg lifts or something and in that first audition, I could barely do three. Missy and I loved that at the end of our training we could climb the rope with our legs pike with no legs support because at the beginning, you looked at rope and you’re like yeah you climb to the top with just your arms—you’re like no, no freakin’ way.

Peregrym: Climbing the rope is the worst thing. It’s awful…The first time I tried to do a giant [swing]…I just didn’t have what it took to get around and I just fell right on my hips and it killed. You can’t do anything about it cause you’re strapped in so it’s not like you can just get off and take a minute. I remember my hands constantly bleeding.

This is the first and only time that I went through such intense training. I literally lived on Aleve. Every morning, I woke up, I was like, it’s fine, my body’s gonna get used to it, eventually, I’ll be okay. I wasn’t okay the whole time.

Curley: Pat and Dona made them do everything. Did all the same conditioning as us. They were not holding back for them. I remember at one point, Vanessa might have fractured her back, I think….but she got a serious injury, which is so on par for the sport. We started telling her all about our injuries, and she’s like, ‘Why do you guys do this?’

Lengies: I got tennis elbow. I got tennis everything. I didn’t know you could get that in things other than your elbow. I fractured my sacral bone.

It was also so fun. We got super fit in a very short period of time…I remember my grandparents being so impressed that I carried their luggage into the car like it was a feather. I could just lift anything at that time in my life. I was so strong.

SooHoo: I remember it being intense. I was eating so much. In the end, I don’t even think I got in shape, look wise, because I was eating so much. And I was young so I still had my baby fat. But I was stronger. I could do a lot more.

Severino: I saw [Peregrym] before for the casting. She worked a lot and her body just changed when I came back for the movie, we were matching up like 100 percent better.

Curley: Missy and Isabel Isabelle Severino, her stunt double, like from the back, it’d be like, Missy? Isabelle? You were afraid to yell out because it was so much the same from behind.

The four months of training, in addition to preparing their bodies for their respective roles, also helped both actresses slip into their characters.

Lengies: There was something I wanted to play that I think was, ‘Who are the gymnasts here whose parents dream this is, not theirs?’ I think in any walk of life, people are living out their parents’ dreams. And sometimes it’s a beautiful thing we call lineage and sometimes it goes against the fiber of the kids being. I definitely did see that in the gym and I wanted to play the truth of that, capture what it would feel like for somebody to make their own choices for the first time.

Peregrym: I think that by being in the gymnastics world for four months before filming, that was the best thing I could have done. To understand Haley to understand what she was walking away from and the work it took to get back into it. I can’t think of a better thing to do.

The gymnastics education didn’t end for the actors once they finished their training before the film shoot. After all, in addition to Curley, there were several world class gymnasts on set as well as highly experienced coaches around. Curley taught Peregrym and SooHoo some uncomfortable truths about wearing gymnastics leotards.

SooHoo: It was very different than [how] dancers wear leotards because I remember I’d always wear it like a dancer wears and Maddy would be like, ‘You need to hike it up.’

Peregrym: I kept pulling mine down and Maddy and the real gymnasts were like, ‘Why are you doing that?’ Like because it’s up to my boobs. It’s so uncomfortable. They’re like, ‘You want to show your hips.’ I was just constantly trying to cover my body with it. They were just laughing at me.

Bridges didn’t need guidance on how to properly attire himself in spandex; rather, he was particularly invested in learning exactly how a coach would behave in the gym and at competition. Ziert helped him get a credential so he could be on the floor at Junior Olympic nationals that year. And on set, he turned to Warren and the gymnasts in the cast for guidance.

Jones: Any sort of thing that needed to be done, [Bridges] needed to know what Pat thought. ‘What’s gonna happen here?’ So Pat would do a lot with him, and then I would take care of the kids. The credit goes to a lot of the athletes too, because they were there and Jessica Miyagi [Peregrym’s second stunt double] or Isabelle would take Missy and be like, ‘No, this is how you’re going to stand. This is what you’re going to do.’

Curley: [Bridges] would pull me aside and be like, ‘Maddy, when you’re doing this’ [referring to] pretend spotting me on a double back off bars—‘what do the coaches do here?’

But no matter how method Bridges was in his approach to becoming a gymnastics coach, he still wasn’t a real coach who actually knew how to spot high-level skills.

Curley: Jeff is pretending to spot me so this was very scary. I know he’s not a real coach. He’s not gonna do anything if I fall. And I’m forced to fall; that’s like the point of the scene. So I’m doing this gienger [a back flip with a half turn uneven bar release], and oh my gosh, it was the most perfect setup, ‘Oh, this is the best gienger I’ve ever done. I have to catch it.’ I got the bar and I finished and did my bail handstand and Jessica was like, ‘What are you doing? You have to understand that time is money.’ But the nice one, they did end up using that as part of one of the montage sequences where I did catch the bar so I didn’t have to feel as guilty. But like from then on, if I was supposed to fall, I fell and if I was supposed to land it, hopefully I did.

Peregrym: My god, the things I saw them do and the fails I saw happen. I mean, I did a lot of the falls in the movie and by lunchtime, when I was falling off of the bars, I couldn’t move. Jessica had to get her acupuncturist to help release the muscles in my body so that we could continue filming that afternoon. The wear and tear is so unbelievable to me. You have to have such a strong mentality to be able to continue doing this and learning the skills because the fails hurt so bad.

Though he couldn’t actually spot Curley, Bridges was generous with her and the rest of the young cast, which was memorable for someone like Curley, who was on her first set.

Curley: I remember one day in particular, I just felt like I did a horrible scene. I was on the verge of tears and he was like, ‘Come on, come here.’ Only he would have this kind of pull; he asked to watch the dailies. He was like, ‘Show me what you don’t like, we’re going to watch it.’ And he got the people to pull up the dailies for me. So they pull it up and we watch this together. And you know, it wasn’t that bad. I’ll never forget that, him just helping. He would show me all of his notes along the side and how he became the character.

SooHoo: I had lost my team jacket, and they only had one, and that was what was needed for the shot in the next shot. And it was like, obviously a huge problem. Wardrobe, I remember, got really upset, which was very warranted. I lost it somehow at lunchtime. And I think she yelled at me and I started crying, which then made it worse because then they had to break everything and redo my makeup, wait till I was back on track again. I remember he had come to my trailer, and he brought his guitar and he just like, serenaded me to try and make me feel better.

Peregrym: I can’t remember what scene we were doing…[but] we get into a fight in that scene and he wanted to run lines, but he said, ‘Run the lines but don’t say the words on the page.’ I was so confused. He’s like, ‘Just paraphrase.’ I was so nervous but we did it and it was so brilliant because what he did was teach me how to drop into my own body with the work that I was going to do in a character so it connected me immediately to what the intention was in the scene. It was the most important thing I’ve ever been taught about acting in terms of connecting in a moment and connecting with another person and understanding where what it is I really wanted and how I really felt without being told.

When Haley first arrives at the Vickerman Gymnastics Academy, she refuses to train. Vickerman engages in an age-old—and inappropriate—training tactic to motivate Haley to work out: group punishment. After putting the girls through hours of conditioning, including having them run outside while he follows them on a lawnmower—a reference, Bendinger said, to a tactic allegedly employed by Bela Karolyi at his Texas ranch—Haley’s teammates later lock her out of the boarding house where they all live. That’s when Vickerman arrives to pick her up and drive her to a diner to try to persuade her to give a damn about gymnastics again. There Haley turns the tables on Vickerman, reciting the pep talk she had heard so many times before from so many others before.

Bendinger: Paper Moon was a very big influence. And Bad News Bears. Those were very formative movies in my childhood and my adolescent development. And I remember sitting with Darrin Okada, we really were trying to capture the dynamic of Paper Moon, which is visually like the adolescent is actually wiser than the adults. And Bad News Bears has that as well. I remember that being a big influence, the protagonist who’s too wise for her years.

Peregrym: I can only relate to that stuff from my own life, being a pastor’s kid. I understood that deeply. You just obey. You just are told who to be how to be and that’s, that’s what you do. Which makes you feel invisible to a certain degree. Everybody has an idea for you. You don’t get to be your own person.

And so for that scene, it’s very, it’s very much about once that happened with her family, and her family broke up because of [gymnastics]. She didn’t believe in herself. She believed in what others said about her.

In the film’s finale, Haley, after seeing Mina get lowballed by the judges, allegedly due to an exposed bra strap, decides to scratch by pulling out her bra straps, strolling down the runway, touching the equipment but not performing a vault, which resulted in an automatic zero score. Then Joanne, who for much of the movie is Haley’s nemesis, follows suit, strutting defiantly down the vault runway and sacrificing her own ambitions for the good of the group. With every other gymnast doing the same, Mina ends up winning the vault title by default. Then Joanne suggests that they do this on the next three events—all except the gymnast that the other gymnasts have designated the “winner” scratch. Scratching—when a gymnast salutes, touches the apparatus, but doesn’t perform—isn’t inherently dramatic.

Bendinger: I started asking about scratches and what that could look like. And once I got the ball rolling and we were shooting it, nobody got it. People were worried.

For the uneven bars, the gymnast “chosen” by the group to win was Nastia Liukin, who played herself in the movies. Just 15 at the time of filming, she was best known at the time as a promising junior and the daughter of 1988 Olympic gold medalist Valeri Liukin. Just two years after the film’s release, Nastia would win the women’s Olympic all-around gold in Beijing.

Ziert was the one who suggested Liukin for a role in the film; unlike most other elite gymnasts, she had already forfeited her NCAA eligibility the year before when she shot an Adidas ad with Nadia Comaneci.

Ziert: I called [Valeri] and he said ‘There’s no way this was going to work.’

Nastia Liukin: My dad told me that [Ziert] had called and they wanted me to be part of it. I remember thinking, ‘Oh my god, that is so cool. I’ve always wanted to be in a movie.’ And my dad was like, ‘That’s really flattering, but at the same time, your career hasn’t even started yet. This is your first year as a senior; you haven’t even gone to Worlds.’ Our goals that year were to make the world team and to hopefully go onto become a world champion, and then, in a few years, the Olympics.

The coach in him [was like], ‘What does this even mean in terms of training? Is this a three month thing, is it a weekend thing? Can we still train and get ready for whatever competition we had coming up?’ Going into my first year as a senior, and then Worlds a few months after that, it was pretty crucial not to miss too many days of training.

Ziert: [Her father told me that] after he had her turn down the part, ‘she worked out every day, [but] she didn’t speak to me for two weeks.’

Liukin: I was just being a 15-year-old teenager. I knew he was right and I think that is why I was more upset. I wanted the best of both worlds.

Liukin ended up accepting a small role and flew out to LA for the shoot.

Liukin discovered that shooting a bar routine for a movie was just as exhausting as training one for the Olympics, perhaps even more so.

Liukin: They kept saying, ‘Okay, let’s just do one more.’ In training, I really would only do, even leading up to the Olympics, three full bar routines and then like, separate parts, and then work separate skills and connections and whatever. At this point [in filming], I don’t exactly know how many full bar routines I had already done, but they kept asking me to do it again. And my dad would just be like, ‘Are you sure? Can you do another one?’ Then at one point, I remember him being like, ‘I think I’m gonna just tell someone there’s really not too many more full bar routines she can do. But we’re more than happy to keep doing the dismount or keep doing parts or separate skills.’

So he spoke up and they were like, ‘We are so sorry. She just made it look so easy. We had no idea that it was that difficult.’ After that, we did a few dismounts and a few different parts.

I don’t think I’ve ever done this many bar routines in a day in my entire life, like leading up to that moment and ever again, even like at the Olympics, or training for the Olympics.

After Liukin “won” the uneven bars, it was time for Wei Wei to do balance beam. While Liukin performed her usual bar routine—one that she would use to win the world title on the event later in 2005—Wei Wei ended up performing a routine that was a tad unorthodox. It featured hip hop and breaking, in addition to acrobatics. For this scene, Bendinger brought in HiHat, the choreographer who worked on the performances in Bring It On. And while SooHoo did some of the dancing, the breaking parts, like the headspin and freezes, were performed by B-girl Shorty.

HiHat: [Bendinger] wanted me to come on board and put an interesting twist for a character called Wei Wei, for her to do the interesting routine on the beam was filled with hip hop and floor freezes. I included a head spin in there. Just very edgy, hip, and unusual for gymnastics. [We had] to find a girl that could do all the stuff that males could do. Shorty was that person who was dope at headspins, dope at freezes.

SooHoo: That was a fun day. They made me a 12-inch-wide beam that I danced on, which was still four feet off the ground. But it was so much wider. My whole foot and fit on the beam. So I felt a lot safer to do a whole dance routine. I had to do some of it on the four inch beam because they would do some top shots.

For the last event, floor, Haley—who has been designated the “winner” by all of the other gymnasts, save one—performs to Fall Out Boy’s “Our Lawyer Made Us Change the Name of this Song So We Wouldn’t Get Sued.”

Bendinger: I thought Marty [Kudelka, Justin Timberlake’s choreographer] did a great job with Missy’s, the fuck-you energy of the character, and letting the character driver the choreography.

Peregrym: At that point, I just had to own it. I just had to be comfortable in my body and trust that it was going to be enough. It’s all technical, like all of the things that we had been training for four months—your toe point, your wrists—as much as we make fun of it in the movie, we were also training all of those things because that’s still the sport.

Just last week, we had a guest star come in and she just came up to me and whispered, ‘Did you really do gymnastics?’

Bendinger: [Peregrym] was dancing to “Like That” by Memphis Bleek. The song we were listening to for the playback for her while she was moving was completely different [than what was played in the movie].

Peregrym: I remember feeling like, ‘Whoa, well, this is so weird, because it was a completely different song that I was dancing to versus what was there.’

The real finale, however, came when Tricia Skilken (who was played by former elite gymnast Tarah Paige), the only gymnast not on board with the whole scratching plan, actually ended up joining the rest of the gymnasts in solidarity and scratching.

Bendinger: So when she finally decides to do the scratch at the end, it was very mild and Gail [Lyon] was like, you have to have her do it stronger. She was doing the bra strap thing but it was too subtle. Thank god Tarah had had enough of those mount and dismount salutes in her bones, that she was able to really do that. That was a big part of the ending that was new.

Adding a bit of authenticity to this final scene was the presence of two perennial Olympic gymnastics commentators: Elfi Schlegel, an Olympian from Canada, and Tim Daggett, a member of the gold medal winning 1984 U.S. men’s Olympic gymnastics team. (Since 2013, Nastia Liukin has commentated alongside Daggett.)

While the “real” gymnasts involved in the film acknowledged that a mass scratching event was not exactly realistic, the feeling undergirding the plot device—that you weren’t being treated fairly and there wasn’t anything you could do about it—was something that many of the gymnasts understood all too well.

Daggett: I don’t think there’s ever been a gymnast at a high level or even a low level that didn’t have some negative experience with judging. Oftentimes, it’s because you think that you were underscored, or even screwed, which certainly, I felt many, many times. All of the people that I know, both on the men’s and the women’s side, they all have many stories so I found it very appropriate in that regard.

One of the things that was notably absent from the film was a romantic subplot for Haley, something that Peregrym appreciated and something that Bendinger had to fight to maintain from the original script.

Peregrym: I love that she wasn’t in a relationship. She wasn’t trying to win a boyfriend. That’s not what this was about. And there are so many movies, if it’s a girl who’s the lead, it’s all about the guy. [Stick It] is all about what she wants.

Bendinger: This was really about her, her relationship to Burt and her teammates; there was no room for a love relationship. The studio tried to shoehorn that in and it didn’t work.

The film was released at the end of April in 2006. Between the time when Bendinger first wrote the script and Stick It’s premiere, the International Gymnastics Federation had made a significant change to sport’s scoring—it had ended the iconic Perfect 10 score. The movie featured the now obsolete scoring system.

Bendinger: I was like ‘What do you mean the 10 is ending? I just did a movie!’ …I was like, Oh, my God, I can’t believe this is happening the year I’m making this movie can be like there was a part of me as a true diehard that was like, this is a disaster.

But the average moviegoer probably had no idea that the scoring system had undergone a radical change. It was between the Olympic Games, which meant that only diehard fans would know about the new scoring paradigm. What turned out to be a bigger issue was the relatively paltry marketing effort behind the film ahead of its premiere.

Bendinger: We found out on opening day that there was only one newspaper ad…It was really hard to have people emailing me from New York saying there are no ads about where the movie was playing and you just got a rave in The New York Times. I remember having the highest per screen average was an exciting moment, but it was also a ‘what would we have done if we’d been more theaters’ kind of moment?

For the actors, despite the fact that they went onto work in many other projects after they finished filming—Peregrym stars in the CBS procedural FBI and Lengies went on to do Glee and is currently shooting the reboot of Turner & Hooch—Stick It sticks with them.

Peregrym: I think I get stopped the most for Stick It. It was a sleeper hit. It was one of those movies that everyone ended up seeing over time.

Lengies: Stick It is the movie I get recognized for the most with other cast members. When I’m coming onto a project, most people are like, ‘I love Stick It.’ I’m working on Turner & Hooch right now and Josh Peck quotes me Stick It lines all the time. He knows the entire movie. He watched it a bunch of times. He absolutely loved it. And when I joined Glee, Kevin McHale was like, ‘Oh, you’re Joanne. I can’t even see you as Vanessa.’ He just kept bringing it up. He was obsessed with it.

Liukin: To this day, if I’m doing a Q&A, people would ask, ‘Oh my god, were you in Stick It? That’s so cool.’ I didn’t realize then that [this movie] would stick with me for the rest of my life. Nothing wrong with it at all, but looking back at it, I was totally going through my most awkward year of my life, braces and all.

Peregrym: Just last week, we had a guest star come in and she just came up to me and whispered, ‘Did you really do gymnastics?’ That’s it. No context.

TIGELAAR: It’s everything you want in a comedy—it’s funny, compelling, empowering, full of heart—but it also explores women’s collective power against systems that don’t make sense. Knowing what we know now about the sport, it’s a comedic glimpse into a really broken system.

It’s hard to watch Stick It 15 years after its theatrical release and not think about the events of the past five years in the sport. The revelation that former USA Gymnastics team doctor Larry Nassar had sexually abused hundreds of gymnastics. The stories of coaches terrorizing their athletes during training and competition. The eating disorders and the injuries.

Stick It lightly touches on some of these themes but they don’t ever become central to the plot or the characters. The main villains of the movie are the judges and the parents who are living out their dreams through their children. Though Burt is initially supposed to embody an unempathetic way of coaching, he’s not truly cruel in the way that some of the gymnasts have described their coaches over the last few years.

But even if the film’s villains are not the sport’s true baddies, the ending, with the gymnasts coming together collectively to take on an unjust system feels especially relevant and cathartic in 2021.

BENDINGER: What does the redemption path look like when there’s no model role models? I think we showed what a path could look like in that movie if you stood up for each other.

Follow Dvora Meyers on Twitter, or at subscribe to her newsletter Unorthodox Gymnastics.