This article originally appeared on VICE Sports.

Over the past half a century or so, medical science seems to have come to the consensus that smoking and rigorous exercise do not mix. Indeed, many doctors are even more down on the ol’ cigarettes these days, this despite the fact that, according to the incontrovertible truth of conventional wisdom, every single member of the medical profession is on 40 Richmond Superkings a day. Between reduced lung capacity, limited blood flow and narrowed arteries— this not including serious conditions like COPD and cancer, both of which are real shithouses—huffing on tobacco habitually is likely to curb long-term athletic potential. That said, there have been a select few sportsmen in the modern era who have flown in the face of the doctor’s orders. Using the logic of modern politics, this means that medical science and the so-called ‘experts’ are out of touch, while in reality no one actually gets lung disease and people should be able to light up in hospitals, nurseries, petrol station forecourts and, most importantly, carpeted pubs.

Videos by VICE

In that select group of sportsmen who have defied the findings of several decades of detailed research on tobacco—and the sinister decrees of the nanny state, of course—the most iconic smokers come from the world of football. Discounting the good old days, when everyone agreed that smoking helped exercise the lungs and should actually be used to aid athletic endeavour , footballers who smoke tend to be either rebels, mavericks and bohemian nonconformists, or men who want to be perceived as such. So Johan Cruyff is surely football’s most famous connoisseur of the cigarette, cultivating as he did a serious habit during his playing days and his career as a manager. Growing up in the surroundings of sixties Amsterdam, the cigarette – a very adult luxury – was no doubt an emblem of rebellion at a time when youth culture was coming into its own in the Netherlands. Cruyff was associated, and associated himself, with the liberalisation of Dutch culture and the anti-establishment, so it was little wonder that fags became a feature of his public image, this alongside his louche aesthetic, effortless fashionability and habit of annoying the conservative orthodoxy with his defiant nonchalance.

While the cigarette may have been something of a statement for Cruyff in his younger years, he soon became reliant on that soothing, familiar dose of nicotine. Barcelona folklore has it that, after his debut match with the club, Cruyff lit up in the changing rooms, went for a shower and then promptly lit up all over again. Supposing that the vast majority of medical professionals are right and smoking does indeed limit athletic prowess, the fact that Cruyff still won La Liga in his first season with the Blaugrana – scoring 16 league goals in the process – serves as even greater testament to his indomitable talents. Despite having a significant disadvantage in terms of recovery time and fitness, Cruyff was on a higher plane than almost all of his contemporaries, carried off on a cloud of fag ash to footballing immortality and global acclaim.

When Cruyff became Ajax manager in 1985, his smoking habit came along with him. From then on, the sight of Cruyff with a cigarette clamped in his mouth as he sat on the sidelines was nothing short of legendary. Cruyff used to smoke throughout games in an effort to dispel his nerves, grey plumes sporadically emerging from the dugout as he sparked up another immaculate, white-filtered tab. He eventually gave up in 1991 while managing Barcelona, famously trading in cigarettes for lollypops after needing double heart bypass surgery, and being told by his doctor that continuing to smoke would drastically shorten his time on this earth.

Though binning the fags certainly didn’t limit his effectiveness as a manager, thinker or footballing philosopher – Cruyff won the Champions League with his pioneering Barca side the following year, and would go on to win three more league titles and a spate of domestic cups – neither did it save him from eventual health complications. The Dutchman required further heart surgery in the late nineties, with a heart attack forcing him to call time on management after leaving Barcelona in 1996. In a Catalan anti-smoking advert filmed soon after he gave up the snouts, Cruyff booted a packet of fags into orbit before delivering the line: “I’ve had two addictions in my life: smoking and playing football. Football has given me everything, whilst smoking almost took it all away.” Those words seemed markedly poignant in the aftermath of his death from lung cancer in 2016, an event which sent football into mourning and suggested that the medical consensus might be sound, after all.

If the cigarette clamped between Cruyff’s pursed lips was a hangover from sixties counterculture as well as a way for a genius mind to unwind in times of high stress, the same might be said of some of the smoking habits of some of his generational peers. So Zdeněk Zeman – the Czech contrarian with a cult following in Italian football who has managed 16 teams, including both Lazio and Roma – has long cultivated a smoking habit that only furthers his eccentric reputation. Andrea Pirlo once described Zeman’s tactics as testing “the very limits of reality”, which perhaps serves as a psychological clue as to why a football coach might still be smoking on the sidelines decades after Cruyff last dragged on a fag. For Zeman, smoking may well remain an act of cultural insubordination, flying in the face of present day sports science in the same way that his often obtuse formations fly in the face of the tactical norm.

While Alsace in the sixties was by all accounts a fairly conservative place, a young Arsène Wenger nonetheless enjoyed a crafty fag or two. Speaking in 2015 after he had fined Wojciech Szczesny a cool $24,952 for smoking in the dressing room, Wenger said: “I grew up in a pub, you could not see to the window because of the smoke and I spent my youth selling cigarettes. I have grown up in a period when I had to accomplish military service. At the end of the month, we got paid by cigarettes. It incited us to smoke. When I was a young boy I grew up surrounded by smokers, and I smoked myself when I became a young coach.”

Wenger, too, put this down to stress, though it is interesting that he identified smoking as a sign of conformity as opposed to dissidence. While Cruyff’s Holland was strongly influenced by a conservative Protestant establishment which, at least outwardly, stressed Christian austerity and traditional values, Wenger’s particular upbringing and the moral outlook of earthy Alsace clearly represented a more accepting environment for a smoker. Still, while puffing louchely away in Alsace may have been worth less in terms of rebellious cachet, Wenger was still a man with a keen interest in sports science, medicine and physiology, and as such he would have known that his penchant for cigarettes would do him no good.

In a way, smoking may have been characteristic of the brave, devil-may-care Arsène Wenger of old. This was a man who, once he became a manager, won Ligue 1 with Monaco despite serial bribery and corruption elsewhere, swanned off to Japan to experience a new culture, then returned to Europe to revolutionise Arsenal and the Premier League. This was a man who would take on English drinking culture, Manchester United and the might of Alex Ferguson, and gave damn well as good as he got despite the fact that he was, in the eyes of the media, just some bloody Frenchman. He had the aloof insouciance to sneer in the face of great risks and dangers, which is a trait all good smokers need when lighting up the next fag.

Now, of course, Arsène would no doubt turn his nose up at a cigarette, for he is not the dauntless soul than he once was. That glimmer of danger has long been extinguished, replaced with a burning self-awareness and a smouldering fear of his footballing mortality. Maybe we’re reading too much into this, in fairness, and he is simply more prudent about his health. Naturally, approaches to smoking and the age people tend to give it up vary from country to country, as Arsène knows all too well. In reference to the now-famous video of him smoking on the touchline during his time at Monaco – brought up during that same Szczesny incident – he said: “The other day on French television they showed me on the bench smoking a cigarette. I didn’t even think it was me. At that time, I remember Marcello Lippi at Juventus smoked a cigar during the whole game, in every game.”

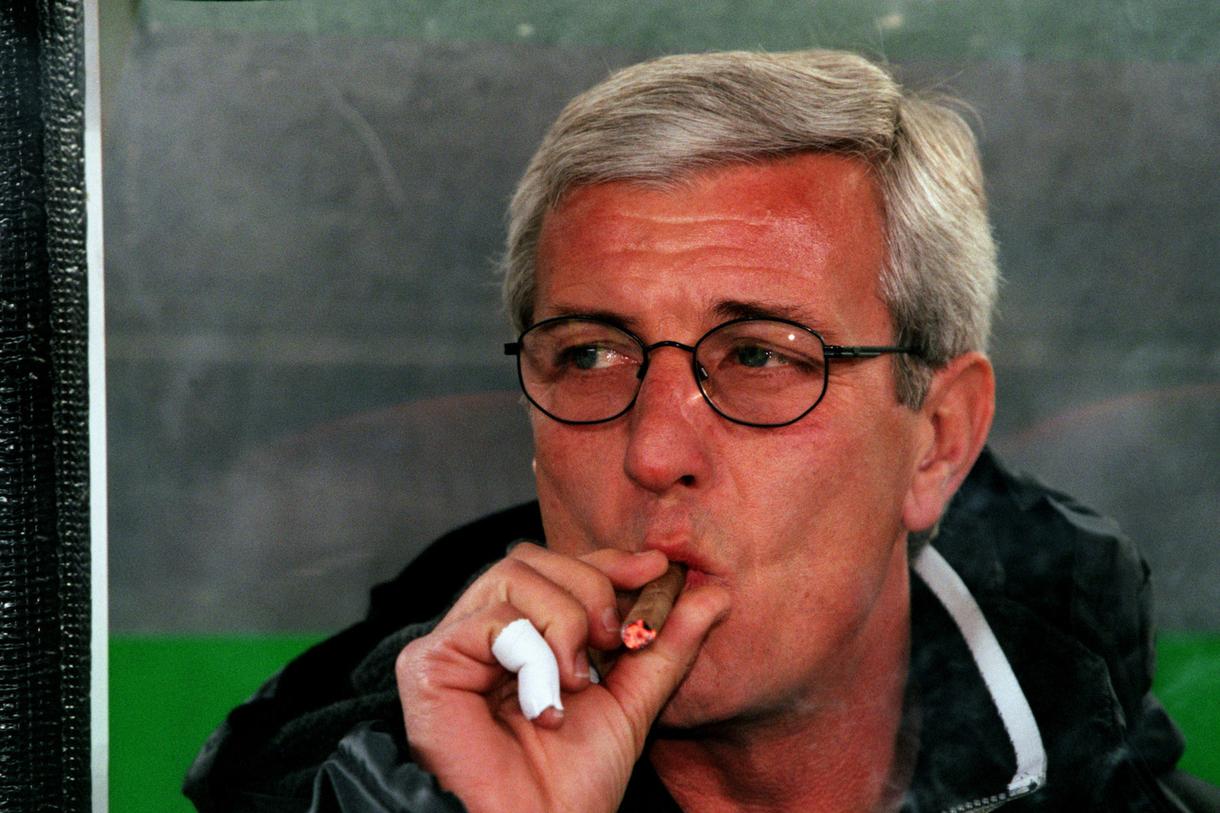

Lippi huffs on a cigar, back in his slightly less wrinkly days. Source: PA Images.

While Arsène appeared to have given up cigarettes by the time he arrived in England, Marcello Lippi was enjoying cigars and cigarillos well into his dotage. This was, of course, really very Italian, with a country forged by history’s most stylish smoker, Giuseppe Garibaldi, clinging on to its love affair with tobacco long after many of its neighbours decided to pack it in. While the image of a white-haired, leathery Lippi sucking moodily on a little cigar most lives up to the Italian smoking stereotype, Carlo Ancelotti strikes a suave figure with a fag in hand, as does Gianluca Vialli. While the former was occasionally spotted puffing away at half-time during his stint as Real Madrid manager, the latter smoked all through his playing days, and was even known to light up straight after being substituted.

Smoking is still an integral part of the Italian national identity in the modern era, with the likes of Vincenzo Iaquinta, Alessandro Nesta and Gianluigi Buffon known to have enjoyed a sneaky cigarette or two. Those are only more recent examples, with the dressing room at Italia 90 probably resembling a smoke-wreathed scene from a Pasolini film. In fairness, the French give them a good run for their money in terms of players on the cigarette, with Zinedine Zidane, David Ginola and Fabien Barthez all indulged for their smoking habits, this on a decreasing scale depending how popular they were with fans. This is telling in terms of the ethics of footballers smoking, with some inclined to take the moral high ground over such well-paid professionals doing down their bodies. Conversely, supporters rarely take issue with a tacit habit when a footballer performs well—in fact their attitude usually falls somewhere between accommodating and faintly admiring—and thus there will always be a whiff of hypocrisy to those who take a stand against what is often the worst kept secret in the game.

Just as smoking has been an integral part of the identity of French and Italian footballers, so too with some of their most talented counterparts from South America. Sócrates had perhaps the most alluring relationship with tobacco, and as a man with a doctorate in medicine his cigarette consumption saw him playing to type. As an educated Brazilian with an interest in philosophy who came to adulthood in the early seventies, he was probably influenced in his habit by the existentialist school, almost all of whom liked a good puff. Meanwhile, Sócrates was a great admirer of both Che Guevara and Fidel Castro, so the constant fug of smoke that surrounded him may well have been a tribute to his political heroes as much as a link to his intellectual roots.

The political significance of tobacco may well have been the same for Maradona, who has tattoos of both Guevara and Castro inked on his skin. While Sócrates preferred several dozen cigarettes a day, Maradona is more often spotted chomping on a huge cigar. In this sense, the Argentine hero has stayed truer to the habit of his idols than his Brazilian contemporary. Still, while Sócrates became a counterculture luminary not unlike Cruyff, challenging his own country’s establishment with a fag hanging casually from his lips, the sight of a bejewelled, latter-day Maradona dragging contentedly on an enormous Cuban feels somewhat less evocative of dissident politics, especially considering his notorious lifestyle, flirtations with the establishment, and fast-and-loose approach to tax .

Maradona smoke cigar. Source: PA Images.

However one interprets the symbolism of smoking for European and South American footballers, we can at least agree they do it better than our own. While Cruyff, Wenger Sócrates and co. all managed to smoke with a sense of panache that belied the health implications of the practise, English footballers who pick up the habit generally look like delinquent twenty-somethings on a two-week piss up in Zante. Often that is quite literally the case, with archetypal lads on tour like Ashley Cole, Wayne Rooney and Jack Wilshere all caught smoking on holiday. There is something about an English lad on the tabs that is uniquely uncool, which perhaps has something to do with the image of a horribly sunburnt Gazza with ciggies hanging out of his ears.

While footballers and managers smoking can be taken to signify something in terms of identity, culture or self-perception, then, it can also be wilfully and determinedly meaningless. When Cruyff or Socrates lit up a fag, it represented to many a form of subversion not only in their role as athletes but also in their capacity as thinkers and men. When Paul Gascoigne shoved two cigarettes up his nose after a day out in the Mediterranean sun, it was perhaps a trivial show of defiance in the face of societal norms and mores, though even that feels like reading too much into it. Then again, maybe in making cigarettes meaningless Gascoigne acknowledged some greater sense of existential indifference, which one might argue is what smoking is all about in the first place.